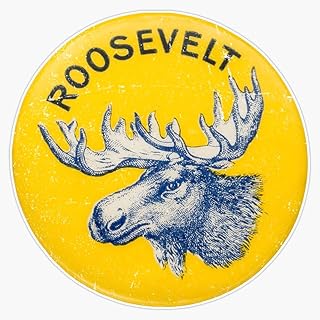

Theodore Roosevelt, a former U.S. President and prominent Republican, founded the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, in 1912 after a fallout with his own party. The primary catalyst for this move was his disagreement with the Republican Party's conservative leadership, particularly his successor, President William Howard Taft, over issues such as trust-busting, conservation, and labor rights. Roosevelt, a staunch progressive, believed the Republican Party had abandoned its reformist principles, prompting him to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination. When he lost the nomination, he decided to run as a third-party candidate, championing a platform of progressive reforms, including women's suffrage, social welfare programs, and antitrust legislation. His bold decision to start his own party reflected his unwavering commitment to progressive ideals and his belief that the existing political system was failing to address the needs of the American people.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dissatisfaction with Republican Party Leadership | Roosevelt was disillusioned with the conservative direction of the Republican Party under President William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor. He disagreed with Taft's policies on tariffs, conservation, and trust-busting. |

| Progressive Reform Agenda | Roosevelt sought to advance a bold progressive agenda, including trust-busting, social welfare programs, conservation, and political reforms like direct primaries and recall elections. The Republican Party was resistant to these ideas. |

| 1912 Republican Primary Defeat | Despite his popularity, Roosevelt lost the Republican nomination to Taft in 1912. He believed the process was rigged against him and decided to challenge Taft directly. |

| Formation of the Progressive Party | In 1912, Roosevelt and his supporters formed the Progressive Party, also known as the "Bull Moose Party," to run against Taft and Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson. |

| Platform of the Progressive Party | The party's platform reflected Roosevelt's progressive ideals, advocating for social justice, economic reform, and government intervention to address social and economic inequalities. |

| Impact on the Election | Roosevelt's third-party candidacy split the Republican vote, allowing Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency with only 42% of the popular vote. |

| Legacy of the Progressive Party | Although short-lived, the Progressive Party's platform influenced future political movements and shaped the modern Democratic Party's progressive wing. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Progressive Discontent with GOP: Roosevelt's frustration with Republican Party's conservative policies and corruption

- New Nationalism Platform: His vision for social justice, regulation, and government intervention in economy

- Republican Rift: Split with Taft over progressive reforms led to third-party formation

- Bull Moose Party Birth: Progressive Party emerged as vehicle for Roosevelt's reform agenda

- Election Impact and Legacy: 1912 campaign reshaped American politics, advancing progressive ideals despite defeat

Progressive Discontent with GOP: Roosevelt's frustration with Republican Party's conservative policies and corruption

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to break away from the Republican Party and form the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose" Party, was rooted in his deep frustration with the GOP's conservative policies and its tolerance for corruption. By 1912, Roosevelt had become increasingly disillusioned with the direction of the Republican Party under President William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor. Taft's administration, which Roosevelt viewed as a betrayal of progressive ideals, prioritized corporate interests and resisted reforms that Roosevelt deemed essential for social and economic justice. This ideological rift set the stage for Roosevelt's dramatic departure and the creation of a new political movement.

Roosevelt's progressive vision clashed sharply with the GOP's conservative stance on key issues such as trust-busting, labor rights, and government regulation. While Roosevelt advocated for aggressive antitrust measures to curb the power of monopolies, Taft's administration took a more lenient approach, favoring compromise over confrontation. For instance, Taft's decision to sue the U.S. Steel Corporation for antitrust violations, despite Roosevelt's earlier approval of its formation, highlighted their diverging philosophies. Roosevelt saw this as a betrayal of his progressive agenda, which aimed to protect consumers and workers from corporate exploitation. His frustration was further compounded by the GOP's resistance to labor reforms, such as the eight-hour workday and workplace safety regulations, which he believed were crucial for improving the lives of ordinary Americans.

Corruption within the Republican Party also played a significant role in Roosevelt's disillusionment. He was appalled by the influence of special interests and political machines, which he believed undermined democratic principles. The infamous "Ballinger-Pinchot Affair," involving allegations of corruption in the Department of the Interior, exemplified the kind of political malfeasance Roosevelt sought to eradicate. While Taft sided with Interior Secretary Richard Ballinger, who was accused of favoring corporate interests in public land disputes, Roosevelt supported Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Forest Service, who exposed the corruption. This scandal widened the ideological and personal rift between Roosevelt and Taft, pushing Roosevelt further away from the GOP.

The breaking point came during the 1912 Republican National Convention, where Roosevelt's progressive supporters were marginalized by Taft's conservative machine. Despite Roosevelt's popularity and grassroots support, Taft secured the nomination through what many viewed as underhanded tactics. Refusing to accept defeat, Roosevelt and his followers bolted from the convention and formed the Progressive Party. His campaign on the Progressive ticket, though ultimately unsuccessful in winning the presidency, galvanized public support for progressive reforms and forced both major parties to address issues like women's suffrage, workers' rights, and government accountability.

In retrospect, Roosevelt's decision to start his own party was a bold response to the GOP's failure to embrace progressive ideals and its tolerance for corruption. His frustration was not merely personal but reflected a broader discontent among Americans who sought a more just and equitable society. While the Progressive Party's impact was short-lived, its legacy endures in the reforms it championed and the enduring call for political accountability. Roosevelt's defiance of the Republican establishment remains a testament to the power of principled leadership in challenging entrenched interests and advancing the common good.

The Tea Party's Rise: Transforming American Politics and Policy

You may want to see also

New Nationalism Platform: His vision for social justice, regulation, and government intervention in economy

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to form the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose" Party, was rooted in his frustration with the Republican Party's conservative shift under President William Howard Taft. Central to his breakaway was the New Nationalism Platform, a bold vision that redefined the role of government in addressing social justice, economic regulation, and inequality. This platform was not merely a political manifesto but a call to arms for a more active, interventionist state—a stark contrast to the laissez-faire policies of the time.

At its core, the New Nationalism Platform championed social justice by advocating for the rights of ordinary citizens against the unchecked power of corporations. Roosevelt proposed a federal income tax, inheritance taxes, and labor protections, including minimum wage laws and restrictions on child labor. For instance, he argued that the government had a duty to ensure fair wages and safe working conditions, particularly for women and children, who were often exploited in factories. This was a radical departure from the era's norm, where such issues were left to state discretion or ignored entirely.

In terms of regulation, Roosevelt envisioned a federal government empowered to oversee industries that affected the public welfare. He called for the creation of a Federal Trade Commission to monitor unfair business practices and antitrust legislation to break up monopolies. His platform also emphasized conservation, with the government playing a key role in managing natural resources for future generations. This regulatory framework was designed to balance economic growth with public interest, ensuring that corporations could not prioritize profit at the expense of society.

The government intervention in the economy under New Nationalism was not about socialism but about creating a level playing field. Roosevelt believed in a partnership between government and business, where the state would set rules to prevent abuses while fostering innovation and competition. For example, he supported public works projects to create jobs and stimulate economic growth, particularly in rural areas. This approach was pragmatic, aiming to address the root causes of inequality rather than merely alleviating symptoms.

Roosevelt's New Nationalism Platform was a response to the Gilded Age's excesses, offering a progressive blueprint for a more equitable society. By prioritizing social justice, robust regulation, and strategic government intervention, he sought to harness the power of the state to protect the vulnerable and rein in corporate overreach. This vision not only justified his break from the Republican Party but also laid the groundwork for modern American liberalism, influencing policies from the New Deal to contemporary debates on economic fairness.

Navigating Political Trust: Identifying Reliable Sources in a Divided Era

You may want to see also

1912 Republican Rift: Split with Taft over progressive reforms led to third-party formation

The 1912 Republican National Convention was a powder keg of ideological conflict, with Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft at its epicenter. Roosevelt, the former president and progressive champion, had expected Taft, his handpicked successor, to continue his reformist agenda. Instead, Taft’s conservative policies, particularly his reluctance to challenge corporate monopolies and his lukewarm support for labor rights, alienated Roosevelt and his progressive allies. This ideological chasm deepened when Taft’s administration filed an antitrust suit against U.S. Steel, a move Roosevelt saw as politically motivated and contrary to his own trust-busting philosophy. The rift was no longer just policy-based; it was personal and irreconcilable.

To understand the split, consider the contrasting approaches of the two leaders. Roosevelt’s progressivism emphasized federal intervention to address social and economic inequalities, while Taft favored judicial restraint and a more limited federal role. For instance, Roosevelt supported the direct election of senators and women’s suffrage, both of which Taft resisted. These differences were not merely philosophical but had tangible consequences, such as Taft’s veto of a bill to reduce tariffs, a measure Roosevelt believed would ease the financial burden on working-class Americans. By 1912, the Republican Party had become a battleground between these competing visions, with neither side willing to yield.

The breaking point came during the 1912 Republican convention, where Taft’s supporters controlled the proceedings and marginalized Roosevelt’s delegates. Accusations of fraud and favoritism flew, culminating in Roosevelt’s dramatic declaration: “We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord.” Denied the nomination, Roosevelt and his followers bolted from the party, forming the Progressive Party, colloquially known as the Bull Moose Party. This third-party formation was not just a protest but a strategic move to push progressive reforms onto the national agenda, even if it meant splitting the Republican vote and handing the election to the Democrats.

The formation of the Progressive Party was a high-stakes gamble with long-term implications. While Roosevelt’s third-party candidacy ultimately failed to win the presidency, it succeeded in shaping the political discourse. His platform, which included a federal income tax, minimum wage laws, and conservation efforts, laid the groundwork for future progressive legislation. The 1912 election also highlighted the fragility of party unity when ideological differences become irreconcilable. For modern political strategists, the lesson is clear: when a party fails to accommodate diverse viewpoints, splintering becomes inevitable, and third-party movements can emerge as powerful catalysts for change.

In practical terms, the 1912 Republican rift offers a cautionary tale for political parties today. To avoid similar schisms, parties must foster internal dialogue and compromise, ensuring that diverse factions feel represented. For activists and reformers, the episode underscores the importance of strategic timing and coalition-building. While third-party efforts often face uphill battles, they can force mainstream parties to adopt more progressive policies. As Roosevelt himself demonstrated, sometimes breaking away is the only way to break through.

Unequal Voting Politics: Understanding Power Imbalances in Democratic Systems

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bull Moose Party Birth: Progressive Party emerged as vehicle for Roosevelt's reform agenda

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to form the Progressive Party, affectionately dubbed the Bull Moose Party, was a bold move fueled by frustration and a relentless drive for reform. By 1912, Roosevelt, a former Republican president, had grown disillusioned with the conservative drift of his party under President William Howard Taft. Taft's reluctance to embrace Roosevelt's progressive agenda, which included trust-busting, labor rights, and conservation, created a rift that could not be mended. Roosevelt's response was not to retreat but to revolutionize, launching a third party that would serve as a vehicle for his vision of a more just and equitable America.

The birth of the Progressive Party was a strategic maneuver to bypass the entrenched interests within the Republican Party. Roosevelt's progressive ideals, such as regulating corporations, protecting consumers, and expanding social welfare, were met with resistance from the party's conservative wing. By forming his own party, Roosevelt aimed to create a platform unencumbered by these constraints, allowing him to advocate directly for his reform agenda. The party's nickname, the Bull Moose Party, originated from Roosevelt's famous declaration that he felt "as strong as a bull moose," symbolizing his resilience and determination to challenge the status quo.

To understand the significance of this move, consider the political landscape of the time. The early 20th century was an era of rapid industrialization and growing inequality, with many Americans demanding reforms to address these issues. Roosevelt's Progressive Party tapped into this sentiment, offering a clear alternative to the Democratic and Republican parties. The party's platform included groundbreaking proposals such as women's suffrage, a minimum wage, and the direct election of senators—ideas that were ahead of their time. By aligning himself with these causes, Roosevelt positioned the Progressive Party as a force for change, attracting a diverse coalition of reformers, labor activists, and middle-class voters.

However, starting a third party is no small feat, and Roosevelt faced significant challenges. One major hurdle was securing ballot access in all 50 states, a logistical nightmare that required extensive organization and resources. Additionally, the party had to contend with the established machinery of the two major parties, which dominated media coverage and campaign financing. Despite these obstacles, the Progressive Party made a remarkable showing in the 1912 election, with Roosevelt winning 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes—a testament to the appeal of his reform agenda.

In retrospect, the Bull Moose Party's emergence was a pivotal moment in American political history. While it did not win the presidency, it forced the major parties to address progressive issues, many of which were later adopted into law. Roosevelt's decision to start his own party was not just a personal gambit but a strategic effort to reshape the nation's political discourse. For those seeking to drive change today, the story of the Progressive Party offers a valuable lesson: sometimes, the most effective way to challenge the system is to build a new one. Practical tip: When advocating for reform, assess whether existing platforms align with your goals. If not, consider creating a new vehicle to amplify your voice and mobilize supporters.

Which Political Party Uses the Buffalo as a Symbol?

You may want to see also

Election Impact and Legacy: 1912 campaign reshaped American politics, advancing progressive ideals despite defeat

The 1912 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, not because of its winner, but due to the seismic shifts it triggered in the nation's ideological landscape. Theodore Roosevelt's decision to form the Progressive Party, or the "Bull Moose" Party, after a fallout with the Republican establishment, was a bold move that challenged the two-party dominance and brought progressive reform to the forefront of national discourse. This campaign's impact extended far beyond the election results, leaving an indelible mark on the country's political trajectory.

A Progressive Platform and Its Reach: Roosevelt's Progressive Party platform was a comprehensive manifesto for reform, advocating for a range of issues that still resonate today. It called for the regulation of corporations, women's suffrage, social welfare programs, and environmental conservation. The party's influence was such that many of these ideas were not confined to the fringes but gained traction across the political spectrum. For instance, the eventual winner of the 1912 election, Democrat Woodrow Wilson, adopted several progressive policies during his presidency, including the establishment of the Federal Reserve and the introduction of antitrust legislation. This demonstrates how Roosevelt's third-party challenge forced the major parties to engage with progressive ideals, thereby shaping the political agenda for years to come.

Redefining Political Engagement: The 1912 campaign also revolutionized political strategies and voter engagement. Roosevelt's energetic and charismatic style, coupled with his extensive whistle-stop train tour across the country, set a new standard for retail politics. He held large rallies, gave numerous speeches, and even survived an assassination attempt, all of which generated unprecedented media coverage. This approach not only energized his base but also attracted new voters, particularly women and young people, who were inspired by his progressive vision. The campaign's ability to mobilize and engage citizens around a set of ideals, rather than just party loyalty, was a significant departure from traditional political tactics.

Long-Term Policy Influence: Despite Roosevelt's defeat, the progressive policies he championed continued to gain momentum. The 1912 election served as a catalyst for future reforms, many of which were implemented in the subsequent decades. For example, the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, was ratified in 1920, and the New Deal era of the 1930s saw the expansion of social welfare programs and further regulation of business. The environmental conservation efforts Roosevelt advocated for also bore fruit, with the establishment of numerous national parks and the creation of the National Park Service in 1916. This demonstrates how the 1912 campaign's impact was not immediate but rather a gradual, enduring influence on American policy.

In the context of political party formation, the 1912 election offers a unique case study. Roosevelt's Progressive Party, though short-lived, demonstrated the power of a third party to disrupt the status quo and drive policy change. It showed that a focused, issue-driven campaign can capture the public imagination and force established parties to adapt. This strategy has been emulated by various third-party candidates and movements throughout history, each seeking to replicate the impact of Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party. The 1912 campaign's legacy is a testament to the potential for progressive ideals to shape American politics, even in the face of electoral defeat.

Uniting Voters: How Political Parties Bridge Electorates for Common Goals

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Theodore Roosevelt started his own political party, the Progressive Party (also known as the "Bull Moose Party"), in 1912 because he was dissatisfied with the conservative policies of the Republican Party, particularly under President William Howard Taft, his handpicked successor.

Roosevelt broke away due to disagreements over progressive reforms, including trust-busting, conservation, and labor rights. He felt the Republican Party under Taft was too aligned with corporate interests and not committed enough to social and economic justice.

Roosevelt's Progressive Party candidacy split the Republican vote, allowing Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency with only 42% of the popular vote. This outcome significantly weakened the Republican Party and reshaped the political landscape.

The Progressive Party advanced key reform ideas, such as women's suffrage, antitrust legislation, and social welfare programs, many of which were later adopted by both major parties. While the party dissolved after 1916, its influence on American politics and policy was lasting.