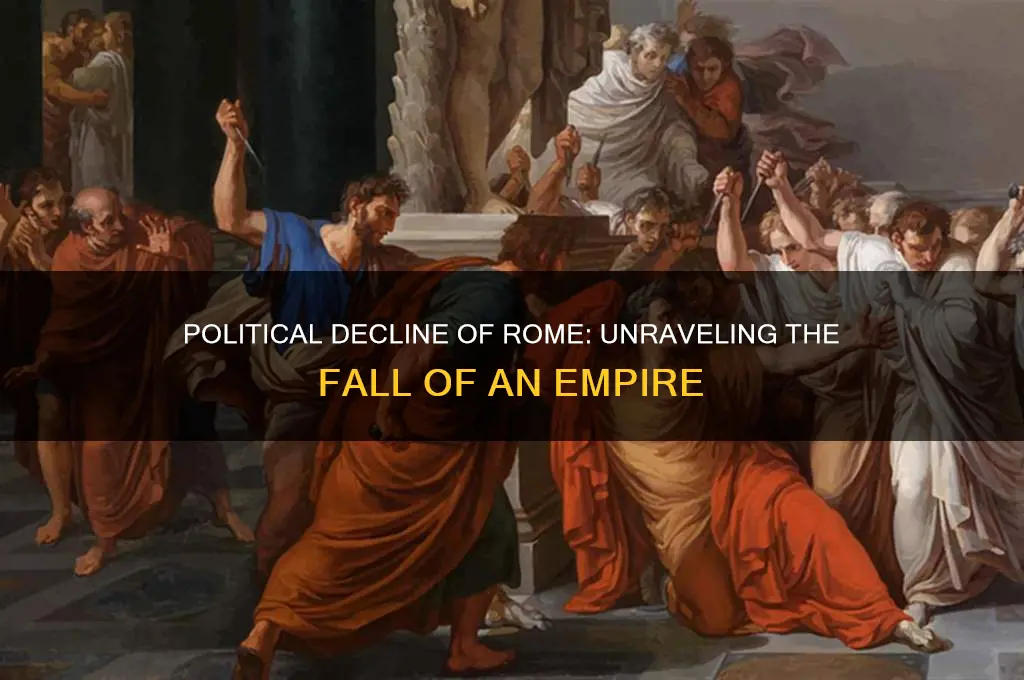

The fall of Rome politically is a complex and multifaceted topic that has been debated by historians for centuries. At its peak, the Roman Empire was a formidable power, stretching across three continents and boasting a sophisticated system of governance, law, and infrastructure. However, by the 5th century AD, the empire began to crumble, ultimately leading to the deposition of the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in 476 AD. Political instability, economic decline, and external pressures from invading tribes all contributed to the empire's downfall. The Roman government, once a model of efficiency, became plagued by corruption, inefficiency, and power struggles, as emperors and military leaders vied for control. Meanwhile, the empire's vast territories became increasingly difficult to manage, with distant provinces often left to fend for themselves. As the central government weakened, local leaders and military commanders began to assert their authority, further fragmenting the empire and setting the stage for its eventual collapse.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Economic Decline | Over-reliance on slave labor, inflation, land concentration in hands of elites, heavy taxation. |

| Military Overstretch | Overextended borders, reliance on foreign mercenaries, decreased loyalty of the legions. |

| Political Instability | Frequent leadership changes, power struggles, assassinations, rise of military dictators. |

| External Pressure | Invasions by barbarian tribes, weakened border defenses, inability to repel attackers. |

| Corruption and Inefficiency | Bureaucratic corruption, mismanagement of resources, decline in civic virtue. |

| Social and Cultural Decay | Decline in traditional Roman values, moral decay, increasing inequality, urban decay. |

| Religious and Ideological Shifts | Rise of Christianity, loss of traditional Roman religious practices, ideological divisions. |

| Administrative Overburden | Inefficient governance, inability to manage vast territories, over-centralization. |

| Health and Demographic Crisis | Plagues, declining birth rates, reliance on immigration to sustain population. |

| Loss of Legitimacy | Erosion of trust in Roman institutions, perceived illegitimacy of rulers, decline of the Senate's authority. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Military Overstretch and Weakening Borders: Overextended legions, inadequate defenses, and barbarian invasions strained Roman military capabilities

- Economic Decline and Taxation: Inflation, land exploitation, and heavy taxes weakened the economy and public support

- Political Corruption and Instability: Frequent leadership changes, power struggles, and corrupt officials eroded governance

- Rise of the Eastern Empire: Shift of power to Constantinople divided resources and attention from the West

- Internal Strife and Civil Wars: Frequent conflicts between factions and generals destabilized political unity and authority

Military Overstretch and Weakening Borders: Overextended legions, inadequate defenses, and barbarian invasions strained Roman military capabilities

The Roman Empire's political decline was significantly exacerbated by Military Overstretch and Weakening Borders, a critical factor that undermined its stability and security. At its height, Rome's military was a formidable force, but the vast expanse of its territories became a liability rather than an asset. The empire's borders stretched from Britain to the Near East, requiring constant vigilance and defense. However, maintaining such an extensive frontier became increasingly unsustainable. The legions, once the backbone of Roman power, were overextended, with soldiers spread thinly across thousands of miles. This dispersion weakened their effectiveness, as troops were often unable to respond swiftly to threats in distant regions. The logistical challenges of supplying and reinforcing these far-flung garrisons further strained the empire's resources, leaving many border areas vulnerable to external pressures.

The overextension of the legions was compounded by inadequate defenses along the frontiers. As the empire expanded, the Romans relied heavily on fortified walls, such as Hadrian's Wall in Britain and the Limes Germanicus in Germania, to deter invaders. However, these defenses were not impenetrable, and their maintenance was often neglected due to financial constraints and administrative inefficiencies. The Roman military, once a professional and disciplined force, began to rely more heavily on auxiliary troops and mercenaries, who were less loyal and less effective than the traditional legions. This decline in military quality made it increasingly difficult to repel barbarian incursions, which grew more frequent and bold as the empire's internal weaknesses became apparent.

The barbarian invasions of the 3rd to 5th centuries AD were a direct consequence of Rome's military overstretch and weakened borders. Tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, and Huns exploited the empire's vulnerabilities, launching raids and full-scale invasions that overwhelmed local defenses. The Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, where the Goths decisively defeated a Roman army, marked a turning point, demonstrating the empire's inability to protect its core territories. These invasions not only resulted in territorial losses but also disrupted trade, agriculture, and the economy, further destabilizing the empire. The constant need to fend off external threats diverted resources away from internal governance and infrastructure, exacerbating political and economic decline.

The strain on Roman military capabilities was also evident in the internal fragmentation caused by the need to defend multiple fronts simultaneously. In the 5th century, the empire was divided into the Western and Eastern halves, each facing distinct challenges. The Western Roman Empire, in particular, bore the brunt of barbarian invasions, while the Eastern Empire, with its more defensible borders and stronger economy, managed to endure. The Western Empire's inability to consolidate its forces and respond coherently to external threats highlighted the consequences of military overstretch. Legions were often tied down in one region, leaving other areas exposed, and the central government struggled to coordinate a unified defense strategy.

Ultimately, the weakening borders and overextended legions created a vicious cycle of decline. As the military's effectiveness waned, barbarian invasions intensified, leading to further territorial losses and economic strain. This, in turn, reduced the empire's ability to fund and maintain its military, accelerating its collapse. The fall of Rome in 476 AD, when the last Western Roman Emperor was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer, was the culmination of decades of military overstretch and border insecurity. The once-mighty Roman legions, stretched beyond their limits, could no longer defend the empire against the forces arrayed against it, sealing the fate of the Western Roman Empire.

Why Blue and Red Dominate American Politics: A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Economic Decline and Taxation: Inflation, land exploitation, and heavy taxes weakened the economy and public support

The economic decline of Rome played a significant role in its political fall, as a weakened economy eroded public support and undermined the stability of the empire. One of the primary factors was inflation, which became rampant due to the debasement of Roman currency. To finance wars and maintain public spending, Roman emperors increasingly reduced the silver content in coins, replacing it with cheaper metals. This led to a loss of confidence in the currency, causing prices to skyrocket and savings to lose value. As inflation spiraled out of control, trade suffered, and the purchasing power of the average Roman citizen plummeted, fostering widespread discontent and economic instability.

Another critical issue was land exploitation, which exacerbated economic inequality and weakened the agricultural base of the empire. Large estates, known as *latifundia*, were owned by the wealthy elite, who often used slave labor to maximize profits. This system displaced small farmers, who were unable to compete and were forced into poverty or urban areas. The decline of small-scale farming reduced food production, leading to shortages and higher prices. Additionally, the concentration of land in the hands of a few undermined the traditional Roman social structure, as the middle class—a key pillar of political stability—shriveled. This economic polarization deepened social divisions and weakened public support for the government.

Heavy taxation further strained the Roman economy and alienated both the populace and the provinces. To fund military campaigns, maintain public works, and sustain the lavish lifestyles of the elite, the Roman state imposed crushing tax burdens on its citizens and subject territories. These taxes were often collected by corrupt officials or private tax farmers, who exploited the system for personal gain, adding to the burden. Small farmers, artisans, and merchants bore the brunt of these taxes, while the wealthy elite frequently evaded their share. The oppressive tax system not only stifled economic activity but also fueled resentment and rebellion in the provinces, as local populations felt exploited by Rome’s fiscal demands.

The combination of inflation, land exploitation, and heavy taxation created a vicious cycle of economic decline. As the economy weakened, the government struggled to collect sufficient revenue, leading to further debasement of the currency and increased taxation. This, in turn, deepened public discontent and eroded trust in Roman institutions. The economic hardships faced by the common people made them less willing to support the state, while the elite’s focus on self-preservation over the common good further fractured society. Ultimately, the economic decline undermined Rome’s ability to maintain its vast empire, as it could no longer afford to sustain its military, infrastructure, or public welfare programs, contributing significantly to its political fall.

In conclusion, the economic challenges of inflation, land exploitation, and heavy taxation were deeply interconnected and played a pivotal role in Rome’s political decline. These factors not only weakened the economy but also eroded public support, as citizens and subjects alike grew disillusioned with a system that seemed to prioritize the interests of the elite over the common good. The inability of the Roman state to address these economic issues effectively hastened its collapse, demonstrating the critical link between economic health and political stability.

Are Australian Political Parties Tax Exempt? Exploring the Legal Framework

You may want to see also

Political Corruption and Instability: Frequent leadership changes, power struggles, and corrupt officials eroded governance

The fall of Rome was a complex process influenced by numerous factors, and political corruption and instability played a significant role in its decline. One of the primary manifestations of this instability was the frequent leadership changes that characterized the later stages of the Roman Empire. Between the years 235 and 284 CE, a period known as the Crisis of the Third Century, Rome saw over 20 emperors rise to power, many of whom were assassinated, overthrown, or died in battle. This rapid turnover of leaders created an environment of uncertainty and weakened the central authority, making it difficult to implement long-term policies or maintain stability. The constant power struggles among military leaders, senators, and other factions further exacerbated the situation, as each group sought to advance its own interests at the expense of the empire's well-being.

Power struggles were a pervasive feature of Roman politics during this period, often leading to civil wars and internal conflicts. The Roman army, which had been a key pillar of the empire's strength, became increasingly involved in political affairs, with generals using their military might to influence or seize power. This militarization of politics not only diverted resources away from essential governance tasks but also fostered a culture of competition and rivalry among the elite. The most notorious example is the Year of the Six Emperors (238 CE), where six different individuals claimed the imperial title within a single year, leading to widespread chaos and bloodshed. These power struggles undermined the legitimacy of the central government and eroded public trust in the institution of the emperor.

Corrupt officials further compounded the issues of political instability and leadership changes. As the empire expanded, the administrative apparatus grew more complex, providing ample opportunities for graft, embezzlement, and abuse of power. Provincial governors, tax collectors, and other officials often exploited their positions for personal gain, imposing heavy burdens on the local populations. This corruption not only drained the empire's resources but also alienated the provinces, fostering resentment and discontent. The inefficiency and dishonesty of the bureaucracy made it difficult to address pressing issues such as economic decline, military threats, and social unrest, further weakening the empire's foundations.

The interplay between frequent leadership changes, power struggles, and corrupt officials created a vicious cycle that eroded governance. Incompetent or short-lived rulers were unable to implement effective reforms or maintain the loyalty of the military and the populace. The constant infighting among the elite diverted attention and resources from external threats, such as barbarian invasions, which became increasingly frequent and severe. Moreover, the corruption within the administrative system hindered the efficient collection of taxes and the distribution of resources, exacerbating the empire's financial difficulties. This combination of factors led to a gradual loss of control over the vast territories of the Roman Empire, making it increasingly difficult to maintain unity and order.

In conclusion, political corruption and instability were critical factors in the fall of Rome. The frequent leadership changes, power struggles, and corrupt officials collectively undermined the empire's ability to govern effectively. These issues not only weakened the central authority but also fostered an environment of distrust and discontent among the population. As the political system became increasingly dysfunctional, the empire was left vulnerable to external pressures and internal disintegration, ultimately contributing to its decline and fall. Understanding these dynamics provides valuable insights into the challenges of maintaining a stable and effective government, lessons that remain relevant in the modern world.

Choosing a Political Party: Identity, Values, or Strategic Alignment?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Rise of the Eastern Empire: Shift of power to Constantinople divided resources and attention from the West

The rise of the Eastern Roman Empire, centered in Constantinople, played a significant role in the political decline of the Western Roman Empire. When Emperor Constantine the Great established Constantinople as the new capital in 330 CE, it marked a strategic shift in focus from Rome to the East. This decision was driven by the city's advantageous geographic location, which facilitated trade, defense, and governance. However, this move also initiated a gradual division of resources and attention between the Eastern and Western halves of the empire. As Constantinople flourished, becoming a hub of wealth, culture, and military power, the Western provinces increasingly felt neglected, exacerbating existing political and economic strains.

Constantinople's rise as the political and economic center of the Roman Empire led to a disproportionate allocation of resources to the East. The Eastern Empire controlled vital trade routes, particularly with Asia, which generated substantial wealth. This prosperity allowed the Eastern emperors to maintain a strong military, invest in infrastructure, and consolidate their power. In contrast, the Western Empire, plagued by barbarian invasions and economic decline, struggled to sustain its defenses and administration. The Eastern emperors often prioritized their own interests, diverting troops, funds, and supplies away from the West, leaving it vulnerable to external threats and internal instability.

The division of the empire into Eastern and Western halves under the rule of co-emperors further weakened the West. While the Eastern emperors focused on securing their borders and expanding their influence, their Western counterparts faced mounting challenges with limited support. The Eastern Empire's reluctance to commit significant resources to the West became evident during critical moments, such as the 5th-century barbarian invasions. For instance, when the Visigoths sacked Rome in 410 CE, the Eastern Empire provided minimal assistance, highlighting the growing rift between the two halves. This lack of unity and shared purpose accelerated the Western Empire's decline.

The cultural and administrative differences between the Eastern and Western Empires also contributed to the shift in power. The East, with its Greek-speaking population and strong ties to Hellenistic traditions, developed a distinct identity separate from the Latin-speaking West. Constantinople became a symbol of this Eastern identity, further alienating the Western provinces. As the Eastern Empire embraced its unique heritage, it increasingly viewed the West as a peripheral concern rather than an integral part of the Roman world. This cultural and political detachment deepened the divide, making it harder for the West to rely on Eastern support during its time of need.

Ultimately, the rise of the Eastern Empire and the shift of power to Constantinople created a structural imbalance that undermined the Western Roman Empire. The East's prosperity and stability allowed it to endure for nearly a millennium after the fall of the West in 476 CE. In contrast, the Western Empire, starved of resources and attention, succumbed to internal decay and external pressures. The division of the empire into two distinct entities, with Constantinople as the dominant center, was a critical factor in Rome's political fall, as it fragmented the once-unified Roman world and left the West to fend for itself in an increasingly hostile environment.

Refusing Service Based on Political Party: Legal or Discrimination?

You may want to see also

Internal Strife and Civil Wars: Frequent conflicts between factions and generals destabilized political unity and authority

The decline of Rome's political stability was significantly exacerbated by the relentless internal strife and civil wars that plagued the empire. During the 3rd century CE, known as the Crisis of the Third Century, Rome witnessed a rapid succession of emperors, many of whom were assassinated or overthrown by rival factions. This period of political turmoil was marked by power struggles between military leaders, each vying for control of the empire. The frequent changes in leadership not only weakened the central authority but also eroded public trust in the imperial system. Generals, often commanding the loyalty of their legions, became kingmakers, prioritizing personal ambition over the stability of the state. This fragmentation of power created a cycle of violence and instability that undermined Rome's political cohesion.

The conflicts between factions were often rooted in competing claims to the imperial throne, fueled by regional loyalties and economic interests. For instance, the rivalry between the Senate-backed emperors and those supported by the military frequently escalated into open warfare. The Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE, where Constantine defeated Maxentius, is a notable example of how civil wars became a means to settle political disputes. These internal conflicts diverted resources away from external defense and governance, leaving the empire vulnerable to external threats. Moreover, the constant state of war within the empire led to economic disruption, as trade routes were severed and agricultural production suffered, further weakening Rome's foundations.

The rise of powerful military leaders, such as Septimius Severus and Diocletian, temporarily restored order but often at the cost of centralizing power in the hands of autocrats. This concentration of authority, while stabilizing in the short term, ultimately contributed to the erosion of republican ideals and the Senate's influence. The empire became increasingly reliant on the military for political legitimacy, creating a system where generals held disproportionate power. This militarization of politics meant that the loyalty of the legions often determined the fate of emperors, leading to a precarious balance of power that could be upended by any ambitious commander.

Civil wars also had a profound social impact, deepening divisions within Roman society. The constant upheaval led to the marginalization of certain groups, particularly in the provinces, where local elites often aligned with different factions to secure their interests. This fragmentation of loyalty weakened the sense of a unified Roman identity, as regional identities and allegiances gained prominence. The empire's inability to resolve internal conflicts through peaceful means further alienated its citizens, many of whom began to question the legitimacy of imperial rule.

In conclusion, internal strife and civil wars were a critical factor in Rome's political decline. The frequent conflicts between factions and generals not only destabilized the empire's unity and authority but also created a cycle of violence and mistrust that proved difficult to break. The militarization of politics, economic disruption, and social fragmentation resulting from these internal struggles all contributed to the erosion of Rome's political foundations, paving the way for its eventual fall. Understanding this aspect of Rome's decline offers valuable insights into the dangers of political division and the importance of maintaining a stable and unified governance structure.

Do Mayors Belong to Political Parties? Exploring Their Affiliations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The fall of Rome politically was driven by internal corruption, ineffective leadership, and the division of the empire into East and West, which weakened centralized authority.

Political instability, marked by frequent leadership changes, power struggles, and the rise of military dictators, eroded trust in the government and made it difficult to address external threats and internal issues.

Yes, the Senate's inefficiency, factionalism, and inability to adapt to the empire's growing challenges contributed to political decay, as it failed to provide stable governance or effective solutions.