George Washington, the first President of the United States, deliberately chose not to align himself with any political party during his tenure, a decision rooted in his concerns about the divisive nature of partisanship. In his Farewell Address, Washington warned against the dangers of political factions, arguing that they could undermine the unity and stability of the young nation. He believed that parties would prioritize their own interests over the common good, leading to conflict and gridlock. Washington’s experience during the American Revolution and his role in shaping the Constitution reinforced his commitment to a nonpartisan leadership style, as he sought to foster a sense of national cohesion rather than encourage factionalism. His stance, though idealistic, reflected his vision for a government that transcended party politics and focused on the welfare of the entire country.

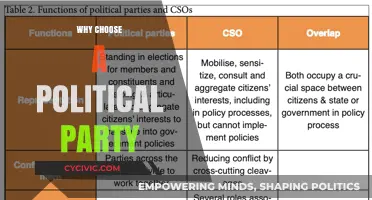

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Belief in Unity | George Washington strongly believed in national unity and feared that political parties would divide the young nation, undermining its stability and cohesion. |

| Precedent Setting | As the first U.S. President, Washington aimed to set a precedent of nonpartisanship, ensuring the presidency remained above factional interests. |

| Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist Tensions | Washington sought to bridge the gap between Federalists (led by Alexander Hamilton) and Anti-Federalists (led by Thomas Jefferson), avoiding alignment with either faction. |

| Warning Against Factions | In his Farewell Address, Washington explicitly warned against the dangers of political factions and partisanship, emphasizing their potential to harm the republic. |

| Focus on National Interests | Washington prioritized the nation's interests over personal or partisan agendas, viewing parties as detrimental to effective governance. |

| Desire for Consensus | He favored consensus-building and compromise over partisan conflict, believing it essential for the nation's growth and survival. |

| Historical Context | The early U.S. political landscape was less structured, and parties were not yet formalized, allowing Washington to govern without formal party affiliation. |

| Legacy of Impartiality | Washington's decision to remain nonpartisan contributed to his enduring legacy as a unifying figure in American history. |

Explore related products

$10.34 $17

What You'll Learn

- Washington's concerns about factionalism dividing the new nation and undermining unity

- His belief in non-partisan leadership to foster national stability and trust

- Warnings against political parties in his Farewell Address

- Early American distrust of parties as threats to democracy

- Washington's focus on national interests over partisan agendas

Washington's concerns about factionalism dividing the new nation and undermining unity

George Washington's aversion to political parties was deeply rooted in his fear that factionalism would fracture the fragile unity of the newly formed United States. In his Farewell Address, he warned against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," arguing that it would place partisan interests above the common good. Washington observed how factions in other republics had historically led to division, mistrust, and ultimately, collapse. For him, the young nation’s survival depended on its ability to prioritize collective welfare over sectional loyalties, a principle he believed political parties would undermine.

To understand Washington’s concern, consider the practical implications of factionalism. When political parties dominate, decision-making shifts from serving the nation to serving the party’s base. This creates a zero-sum game where one group’s gain is perceived as another’s loss, fostering resentment and polarization. Washington feared this dynamic would erode the civic trust necessary for a functioning democracy. For instance, if a party’s primary goal becomes defeating opponents rather than solving problems, the nation’s progress stalls, and unity unravels.

Washington’s stance was not merely theoretical but grounded in the realities of his time. The 1790s saw the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, whose bitter rivalry threatened to destabilize the government. He witnessed how partisan newspapers fueled animosity, turning political disagreements into personal attacks. This environment, he argued, would distract from the critical task of nation-building and leave the country vulnerable to external threats. By avoiding party affiliation, Washington sought to model impartial leadership, demonstrating that the president’s loyalty should be to the nation, not a faction.

A comparative analysis of nations with strong partisan systems versus those with coalition-based governance underscores Washington’s point. In highly polarized systems, gridlock often paralyzes government, while coalition-based models encourage compromise and collaboration. Washington’s vision aligns more closely with the latter, emphasizing shared goals over ideological purity. For modern leaders, this serves as a cautionary tale: fostering unity requires resisting the temptation to exploit divisions for short-term political gain.

In practical terms, Washington’s concerns offer a roadmap for mitigating factionalism today. Leaders can prioritize non-partisan initiatives, such as infrastructure projects or disaster relief, that benefit all citizens regardless of political affiliation. Encouraging cross-party collaboration on key issues and promoting civics education to foster informed, rather than partisan, citizenship can also help. By focusing on shared values and long-term goals, societies can avoid the pitfalls Washington foresaw, ensuring unity remains the cornerstone of their strength.

Neil Gorsuch: Politico's Insights on the Supreme Court Justice

You may want to see also

His belief in non-partisan leadership to foster national stability and trust

George Washington's aversion to political parties was rooted in his profound belief that non-partisan leadership was essential for fostering national stability and trust. During his presidency, he witnessed the emergence of factionalism, particularly between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, which threatened to divide the young nation. Washington feared that political parties would prioritize their own interests over the common good, leading to gridlock, corruption, and a loss of public confidence in government. In his Farewell Address, he warned against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," emphasizing that it could undermine the unity necessary for a fledgling republic to thrive.

To understand Washington's perspective, consider the historical context of his era. The American Revolution had been fought against a monarchy, and the Founding Fathers sought to create a system that avoided the pitfalls of tyranny and division. Washington believed that a non-partisan approach would allow leaders to make decisions based on merit and the nation's best interests rather than party loyalty. For instance, his cabinet included both Federalists and Anti-Federalists, demonstrating his commitment to inclusivity and balanced governance. This approach not only mitigated conflicts but also set a precedent for future leaders to prioritize national unity over partisan gain.

Washington's belief in non-partisan leadership was also deeply tied to his vision of civic virtue. He argued that leaders should act as stewards of the public trust, guided by principles of integrity and selflessness. By avoiding party affiliations, he sought to model a leadership style that transcended personal or factional ambitions. This philosophy is evident in his refusal to seek a third term, a decision that reinforced the importance of democratic transitions and the rejection of power consolidation. His actions underscored the idea that leadership should be a service to the nation, not a platform for personal or partisan advancement.

Practical lessons from Washington's stance can be applied to modern governance. In today’s polarized political landscape, leaders can emulate his approach by fostering cross-party collaboration and prioritizing national interests over ideological purity. For example, bipartisan committees or task forces can be established to address critical issues like healthcare, climate change, or economic reform. Additionally, leaders can commit to transparent decision-making processes, ensuring that policies are driven by evidence and public welfare rather than party agendas. By adopting these practices, contemporary politicians can rebuild public trust and restore stability in governance.

Ultimately, Washington's rejection of political parties was not merely a personal preference but a strategic choice to safeguard the nation's future. His belief in non-partisan leadership as a cornerstone of national stability and trust remains a timeless lesson. In an age where partisan divisions often paralyze progress, Washington’s example serves as a reminder that unity and integrity are the bedrock of effective governance. By embracing his principles, leaders can navigate the complexities of modern politics while upholding the ideals of a democratic republic.

Understanding the Sia Political Machine: Power, Influence, and Strategy Explained

You may want to see also

Warnings against political parties in his Farewell Address

George Washington's Farewell Address stands as a pivotal document in American political history, not least for its prescient warnings about the dangers of political factions. In an era before the solidification of political parties, Washington foresaw the divisive potential of such groups, cautioning that they could undermine the unity and stability of the young nation. His concerns were rooted in the belief that partisan interests would inevitably clash with the common good, leading to strife and disintegration. This foresight was not merely theoretical; it was a call to action, urging future generations to prioritize national cohesion over factional loyalty.

To understand Washington's stance, consider the context of his time. The early United States was fragile, having recently emerged from a revolutionary war and facing internal and external threats. Washington feared that political parties would exacerbate regional and ideological divisions, creating an environment where compromise would become impossible. He argued that factions would prioritize their own power over the welfare of the nation, leading to corruption and the erosion of public trust. His warning was clear: the health of the republic depended on citizens acting as stewards of the collective interest, not as soldiers for partisan causes.

Washington's critique of political parties was not just about their existence but about their tendency to foster animosity and distort public discourse. He observed that factions often manipulated public opinion, using rhetoric to divide rather than unite. In his words, they "agitated the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms." This manipulation, he believed, would weaken the nation's resolve and make it vulnerable to external threats. His solution was not to eliminate disagreement but to encourage a culture of reasoned debate and mutual respect, where differences were resolved through dialogue rather than domination.

Practically speaking, Washington's warnings offer a blueprint for navigating modern political challenges. To heed his advice, individuals should critically evaluate the motives of political parties and their leaders, questioning whether policies serve the broader public or narrow interests. Engaging in cross-partisan dialogue, supporting non-partisan institutions, and fostering civic education are actionable steps to counteract the divisive effects of partisanship. By prioritizing national unity over party loyalty, citizens can honor Washington's vision and strengthen the democratic fabric.

In conclusion, Washington's Farewell Address remains a timeless guide to the perils of political factions. His warnings were not a rejection of political diversity but a call to safeguard the republic from the corrosive effects of partisanship. By understanding and applying his insights, we can work toward a political landscape where the common good prevails, and the nation thrives as a united entity. Washington's legacy challenges us to rise above faction and embrace the principles of unity, reason, and public service.

Victoria Neave's Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party Membership

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Early American distrust of parties as threats to democracy

George Washington’s refusal to align with a political party was rooted in a broader, deeply held belief among early Americans that factions—what we now call political parties—posed a grave threat to the fragile experiment of democracy. This distrust was not merely a personal quirk but a reflection of the era’s political philosophy, shaped by the Enlightenment and the lessons of history. Washington himself warned in his Farewell Address that "the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension… is itself a frightful despotism." His words echoed a widespread fear that parties would prioritize self-interest over the common good, fracturing the nation along ideological lines.

To understand this distrust, consider the historical context. The Founding Fathers had just broken free from a system where loyalty to a single monarch often superseded the needs of the people. They feared that political parties, by fostering blind allegiance to a group rather than the nation, would recreate a similar tyranny. James Madison, in Federalist No. 10, argued that factions were inevitable but warned of their potential to undermine republican governance. Early Americans saw parties as tools for demagogues to manipulate public opinion, a danger Washington highlighted when he cautioned against "cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men" exploiting divisions for personal gain.

This distrust was not theoretical but practical. The 1790s, marked by the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, were a period of intense polarization. Partisanship led to bitter disputes over foreign policy, economic priorities, and the interpretation of the Constitution. Washington observed how these divisions weakened the young nation, making it vulnerable to external and internal threats. His decision to remain above the fray was a deliberate attempt to model unity and demonstrate that leadership could transcend partisan interests.

For modern readers, this historical perspective offers a cautionary tale. While political parties today are seen as essential for organizing political activity, early Americans’ skepticism reminds us of the dangers of unchecked partisanship. Practical steps to mitigate these risks include fostering cross-party collaboration, encouraging issue-based rather than identity-based politics, and promoting civic education that emphasizes shared national values. By studying this era, we can better navigate the tension between party loyalty and democratic integrity.

In conclusion, early American distrust of political parties was not merely a relic of the past but a prescient warning about the fragility of democracy. Washington’s stance was a call to prioritize the nation’s well-being over factional interests, a principle that remains relevant in an age of deepening political divides. By understanding this history, we can work to build a political system that serves the common good rather than the interests of a few.

Curtis Sliwa's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Washington's focus on national interests over partisan agendas

George Washington's refusal to align with a political party was rooted in his unwavering commitment to the nation's collective good over the divisive interests of factions. This principle, articulated in his Farewell Address, warned against the dangers of party politics, which he believed would place partisan victories above the welfare of the country. By remaining independent, Washington sought to embody the role of a unifying leader, ensuring that his decisions were guided by the broader needs of the fledgling United States rather than the narrow agendas of any single group.

Consider the practical implications of Washington's stance in today’s political landscape. In an era where party loyalty often supersedes national priorities, his approach offers a blueprint for leaders to transcend ideological divides. For instance, when addressing critical issues like infrastructure or healthcare, policymakers could emulate Washington by prioritizing solutions that benefit the majority, even if it means compromising on party-specific platforms. This methodical focus on national interests requires leaders to weigh evidence, consult diverse perspectives, and make decisions based on long-term impact rather than short-term political gains.

Washington’s decision to avoid party affiliation was also a strategic move to preserve his credibility as a neutral arbiter. By refusing to align with the Federalists or Anti-Federalists, he maintained the trust of a diverse and often fractious populace. This neutrality allowed him to navigate contentious issues, such as the national bank or foreign policy, without being perceived as favoring one faction over another. For modern leaders, this serves as a cautionary tale: aligning too closely with a party can erode public trust and limit one’s ability to act as a mediator in times of crisis.

A comparative analysis of Washington’s era and contemporary politics reveals the consequences of prioritizing party over nation. In the 1790s, the emergence of political factions threatened to destabilize the young republic, prompting Washington’s warning against "the baneful effects of the spirit of party." Today, hyper-partisanship often leads to legislative gridlock, preventing progress on urgent issues like climate change or economic inequality. By contrast, Washington’s focus on national unity enabled him to foster stability and lay the foundation for a resilient nation. This historical example underscores the enduring value of placing country above party.

To implement Washington’s principle in modern governance, leaders can adopt specific practices. First, establish bipartisan committees to address key national challenges, ensuring diverse viewpoints are represented. Second, publicly commit to transparency in decision-making, demonstrating that actions are driven by evidence and national benefit rather than party loyalty. Finally, encourage civic education that emphasizes the importance of unity and compromise, fostering a culture where citizens value collective progress over partisan victory. By adopting these steps, leaders can honor Washington’s legacy and steer their nations toward a more cohesive future.

Democracy Without Parties: A Feasible Political Reality or Illusion?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Washington opposed the formation of political parties, believing they would divide the nation and undermine the unity necessary for the young country’s stability.

No, George Washington never formally belonged to a political party. He remained independent throughout his presidency, though his policies later influenced the formation of the Federalist Party.

Washington warned against political parties in his Farewell Address because he feared they would create factions, foster selfish interests, and threaten the Republic’s integrity.

Washington’s lack of party affiliation set a precedent for nonpartisanship in the presidency, though it also led to the emergence of competing factions, notably Federalists and Anti-Federalists, during his successors’ terms.