American political parties are often described as decentralized due to their unique organizational structure, which contrasts sharply with the centralized models seen in many other democracies. Unlike parties in parliamentary systems, where leadership and decision-making are concentrated at the national level, American parties operate as loose coalitions of state and local organizations with significant autonomy. This decentralization stems from the federal nature of the U.S. government, where power is divided between the national and state governments, allowing state party committees to wield considerable influence over candidate selection, fundraising, and campaign strategies. Additionally, the absence of a strong, centralized party hierarchy means that individual candidates, particularly in congressional and state-level races, often build their own independent political brands and organizations, further fragmenting party unity. This structure reflects the broader American political culture, which values local control and individualism, but it also contributes to challenges in coordinating policy agendas and maintaining consistent party messaging across the nation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Weak Central Organization | Unlike parties in many other democracies, American political parties have a relatively weak central organization. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Republican National Committee (RNC) have limited control over party members and elected officials. |

| State-Based Structure | American political parties are organized at the state level, with each state having its own party committees and rules. This leads to significant variation in party platforms, strategies, and candidate selection across states. |

| Primary Elections | Candidates for office are typically chosen through primary elections, where voters within a party select their preferred candidate. This process empowers individual voters and reduces the influence of party leaders in candidate selection. |

| Faction Formation | The decentralized nature allows for the formation of factions within parties, such as the progressive wing of the Democratic Party or the libertarian wing of the Republican Party. These factions can significantly influence party policy and direction. |

| Limited Party Discipline | Elected officials have considerable autonomy and are not strictly bound by party platforms or leadership directives. This allows for greater individual freedom but can also lead to internal party divisions. |

| Focus on Fundraising | Due to the high cost of political campaigns in the US, parties and candidates rely heavily on individual donations and fundraising efforts. This further decentralizes power and influence within the party structure. |

| Federal System | The US federal system, with power divided between the federal government and the states, contributes to the decentralized nature of political parties. State governments have significant autonomy, which extends to party organization and politics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- State-Level Autonomy: Parties operate independently in each state, with unique platforms and leadership

- Local Fundraising: Campaigns rely on local donations, reducing national party financial control

- Primary Systems: State-run primaries determine candidates, not national party leadership

- Faction Influence: Interest groups and factions shape policies more than national party directives

- Decentralized Messaging: Candidates craft their own messages, often diverging from national party narratives

State-Level Autonomy: Parties operate independently in each state, with unique platforms and leadership

American political parties are often described as decentralized due to the significant autonomy granted to their state-level counterparts. This autonomy allows parties in each state to operate independently, crafting unique platforms and selecting distinct leadership that reflects local priorities and values. Unlike centralized party systems where national directives dominate, American parties function more like federations of state organizations, each with its own identity and operational freedom.

Consider the Democratic and Republican parties in Texas versus California. In Texas, both parties often emphasize border security, energy policy, and gun rights, reflecting the state’s conservative leanings and economic interests. Meanwhile, California’s Democratic Party focuses heavily on environmental regulations, social justice, and progressive taxation, aligning with the state’s liberal majority. These differences aren’t just rhetorical; they shape candidate recruitment, campaign strategies, and legislative agendas. For instance, a Republican candidate in Texas might prioritize oil industry support, while one in California might focus on tech industry regulation.

This state-level autonomy is rooted in the U.S. Constitution’s federalist structure, which reserves substantial power for states. Political parties, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, have evolved to mirror this framework. State parties control their own primaries, fundraising, and voter outreach, often with minimal interference from national headquarters. This independence is further reinforced by the Electoral College system, which incentivizes parties to tailor their messaging and strategies to win state-level elections rather than relying solely on a national playbook.

However, this decentralization isn’t without challenges. It can lead to inconsistencies in party branding and policy positions, making it difficult for national leaders to present a unified front. For example, a Democrat in West Virginia might support coal industry subsidies, while one in New York might advocate for renewable energy mandates. Such disparities can complicate efforts to pass federal legislation or coordinate national campaigns. Yet, this flexibility also allows parties to adapt to diverse electorates, increasing their relevance in a geographically and ideologically varied country.

To navigate this system effectively, political strategists and activists must understand the nuances of state-level party operations. Engaging with local party leaders, attending state conventions, and aligning with regional priorities are essential steps for anyone seeking to influence party politics. While national platforms provide broad guidelines, the real action—and opportunity for impact—happens at the state level, where autonomy reigns and local voices drive the agenda.

Populist Party's Political Reforms: Key Demands and Impact on Democracy

You may want to see also

Local Fundraising: Campaigns rely on local donations, reducing national party financial control

American political campaigns often thrive on the strength of local fundraising, a practice that significantly diminishes the financial grip of national party organizations. This reliance on local donations is a cornerstone of the decentralized nature of American political parties. Unlike centralized systems where party headquarters dictate funding allocation, U.S. campaigns frequently tap into grassroots support, fostering a bottom-up financial model. For instance, a congressional candidate in Texas might secure substantial contributions from local businesses, community leaders, and individual donors within their district, rather than waiting for a large check from the national party committee. This approach not only empowers local communities but also ensures that campaigns are more attuned to regional issues and priorities.

The mechanics of local fundraising are both strategic and practical. Campaigns often host small-dollar donation drives, town hall meetings, and community events to engage potential donors directly. These efforts are complemented by digital platforms that allow for easy online contributions, often targeting specific demographics or geographic areas. For example, a campaign in a rural area might focus on agricultural stakeholders, while an urban campaign could target tech industry professionals. This targeted approach maximizes the potential for local support, reducing the need for substantial national party funding. However, it’s crucial for campaigns to balance these efforts with compliance to Federal Election Commission (FEC) regulations, ensuring transparency and adherence to contribution limits, such as the $3,300 individual donation cap per election cycle.

One of the most compelling advantages of local fundraising is its ability to foster a sense of ownership among donors. When individuals contribute to a campaign in their own backyard, they feel more invested in the outcome. This engagement translates into not just financial support but also volunteer hours, word-of-mouth promotion, and increased voter turnout. For instance, a study by the Campaign Finance Institute found that campaigns relying heavily on local donations often experienced higher levels of community involvement compared to those dependent on national party funds. This symbiotic relationship between campaigns and their local supporters underscores the decentralized ethos of American politics.

However, local fundraising is not without its challenges. Campaigns must navigate the complexities of building a robust donor base from scratch, often with limited resources. Small campaigns, in particular, may struggle to compete with well-funded national party efforts or self-funded candidates. To mitigate this, campaigns should adopt a multi-pronged strategy: leveraging social media to amplify their reach, partnering with local organizations for joint fundraising events, and offering incentives like campaign merchandise or exclusive updates to donors. Additionally, campaigns should prioritize building long-term relationships with donors, ensuring that their support extends beyond a single election cycle.

In conclusion, local fundraising serves as a vital mechanism for reducing national party financial control and reinforcing the decentralized structure of American political parties. By tapping into grassroots support, campaigns not only secure the necessary funds but also cultivate a deeper connection with their communities. While the process demands strategic planning and adherence to regulatory requirements, the benefits—increased donor engagement, heightened community involvement, and greater autonomy—far outweigh the challenges. For any campaign aiming to thrive in the decentralized landscape of American politics, mastering the art of local fundraising is not just advantageous—it’s essential.

Unveiling Gary Palmer's Political Affiliation: Which Party Does He Represent?

You may want to see also

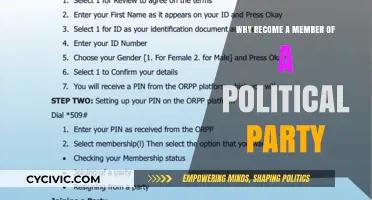

Primary Systems: State-run primaries determine candidates, not national party leadership

In the United States, the process of selecting candidates for federal elections is a prime example of the country's decentralized political party system. Unlike many other democracies, where party leadership plays a central role in choosing candidates, American political parties rely on state-run primaries to determine their nominees. This system, which emerged in the early 20th century as a reform to curb party boss influence, has become a cornerstone of the nation's electoral process. As of 2022, 41 states and the District of Columbia use either a closed or open primary system, while the remaining states employ caucuses or conventions, further emphasizing the state-centric nature of candidate selection.

Consider the practical implications of this system. Each state sets its own rules for primaries, including eligibility requirements, voting methods, and dates. For instance, New Hampshire traditionally holds the first primary in the nation, a status it fiercely protects through state law. This state-by-state approach creates a complex calendar of elections, where candidates must navigate varying landscapes of voter demographics, campaign finance regulations, and local issues. A candidate who performs well in Iowa's caucuses, for example, may struggle in New York's diverse primary electorate, highlighting the need for adaptable strategies. This diversity in primary systems not only tests candidates' organizational skills but also ensures that they address a wide range of concerns, from agricultural policy in the Midwest to urban development in coastal states.

From a comparative perspective, the American primary system stands in stark contrast to those of countries like the United Kingdom or Germany, where party leadership plays a dominant role in candidate selection. In these nations, centralized control allows parties to present a more unified front, but it can also limit grassroots influence. The U.S. system, while chaotic, empowers local voters and activists, often leading to unexpected outcomes. For example, the 2016 presidential primaries saw the rise of political outsiders like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, who leveraged state-level support to challenge establishment candidates. This dynamic underscores the decentralized nature of American parties, where power is distributed across states rather than concentrated at the national level.

However, this decentralization is not without challenges. The state-run primary system can lead to inconsistencies in how candidates are chosen, with some states favoring more extreme candidates due to low turnout or polarized electorates. Additionally, the lack of national coordination can result in fragmented campaigns, where candidates focus on winning individual states rather than building a cohesive national message. To mitigate these issues, parties often step in during the general election phase, providing resources and strategic guidance. Yet, this intervention is reactive rather than proactive, further illustrating the limited role of national party leadership in the candidate selection process.

In conclusion, the state-run primary system is a key factor in understanding why American political parties are decentralized. By placing the power to choose candidates in the hands of state voters, this system fosters local engagement and diversity in representation. However, it also introduces complexities and challenges that reflect the broader tensions within the U.S. political landscape. For anyone seeking to understand or engage with American politics, grasping the nuances of this primary system is essential. It is not just a mechanism for selecting candidates but a reflection of the nation's commitment to federalism and grassroots democracy.

Political Party Perspectives: Understanding Their Core Beliefs and Policies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.97 $21.95

$13.99 $19.99

Faction Influence: Interest groups and factions shape policies more than national party directives

American political parties often resemble loose coalitions rather than rigid hierarchies, a phenomenon driven significantly by the outsized influence of interest groups and factions. These entities, operating within and across party lines, wield considerable power in shaping policies, frequently overshadowing national party directives. Consider the National Rifle Association (NRA) or the Sierra Club, whose lobbying efforts and grassroots mobilization can dictate a party’s stance on gun control or environmental regulations, regardless of the national party platform. This dynamic underscores a critical reality: in the U.S., policy agendas are often forged in the trenches of faction influence, not in the boardrooms of party leadership.

To understand this mechanism, examine the legislative process. Interest groups strategically target specific members of Congress, leveraging campaign contributions, voter mobilization, and public pressure to advance their agendas. For instance, during the 2018 midterm elections, healthcare advocacy groups like Protect Our Care ran targeted campaigns in key districts, influencing Democratic candidates to prioritize Medicare expansion. This localized pressure often supersedes broader party strategies, as representatives and senators must balance national party goals with the demands of powerful factions in their constituencies. The result? A decentralized policy-making process where faction influence is the linchpin.

This system has practical implications for both policymakers and citizens. For lawmakers, aligning with influential factions can secure reelection and legislative success, but it also risks alienating other party members or the broader electorate. Citizens, meanwhile, must navigate a political landscape where their representatives’ priorities may reflect faction interests more than party ideals. To engage effectively, voters should track not only party platforms but also the interest groups funding and endorsing their candidates. Tools like OpenSecrets.org provide transparency into campaign financing, offering a roadmap to understand faction influence in real time.

A comparative lens further illuminates this dynamic. In countries with centralized party systems, such as the United Kingdom, party whips enforce discipline, ensuring legislators vote in line with party directives. In contrast, the U.S. system allows factions to exploit ideological diversity within parties, creating opportunities for cross-party alliances. For example, the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus in Congress often bridges partisan divides on issues like infrastructure, driven by shared faction interests rather than party loyalty. This fluidity, while fostering compromise, also highlights the fragmented nature of American political parties.

In conclusion, the decentralized nature of American political parties is not merely a structural quirk but a reflection of faction influence dominating policy-making. Interest groups and factions act as the invisible hands steering legislative agendas, often with greater efficacy than national party leadership. For those seeking to effect change, understanding this dynamic is essential. Engage with factions, monitor their activities, and recognize their role in shaping the policies that govern our lives. In the American political arena, factions are not just players—they are the game itself.

Fractional Politics: How Partial Interests Shape Party Dynamics and Policies

You may want to see also

Decentralized Messaging: Candidates craft their own messages, often diverging from national party narratives

In the American political landscape, candidates often act as independent brands, tailoring their messages to resonate with local audiences rather than adhering strictly to national party platforms. This phenomenon is particularly evident in swing districts, where a one-size-fits-all approach can alienate voters. For instance, a Democratic candidate in a rural, conservative-leaning area might emphasize support for gun rights or agricultural subsidies, while downplaying more progressive national stances on issues like healthcare or climate change. This strategic divergence allows candidates to appeal to the unique priorities of their constituents, even if it means stepping away from the party’s broader narrative.

Consider the mechanics of this decentralized messaging: candidates and their teams conduct hyper-localized polling, focus groups, and community engagement to identify the issues that matter most to their electorate. They then craft messages that align with these concerns, often blending personal anecdotes and local references to build trust. This approach is both practical and necessary, given the vast cultural and ideological differences across the United States. For example, a Republican running in an urban district might highlight economic growth and public safety, while a candidate in a suburban area might focus on education and infrastructure. The result is a patchwork of campaign messages that reflect the diversity of American communities rather than a monolithic party line.

However, this decentralization is not without its challenges. While it allows candidates to connect authentically with voters, it can also create inconsistencies in party branding and dilute the impact of national messaging. Party leaders must strike a delicate balance between providing broad guidance and allowing candidates the freedom to adapt. For instance, during the 2020 elections, some Democratic candidates in red states distanced themselves from progressive labels, instead emphasizing bipartisanship and local solutions. This tactical flexibility helped them gain traction in otherwise hostile territories, but it also raised questions about the party’s unified vision.

To navigate this dynamic effectively, candidates should follow a three-step process: first, identify the top three issues in their district through data-driven research; second, develop a narrative that ties these issues to their personal story and values; and third, test this message through small-scale campaigns before scaling up. Caution should be taken to avoid over-pivoting, as voters can detect inauthenticity. For example, a candidate who suddenly adopts a stance on an issue they’ve never addressed before risks appearing opportunistic. The key is to find the sweet spot where local priorities intersect with broader party principles, ensuring both relevance and consistency.

In conclusion, decentralized messaging is a double-edged sword in American politics. It empowers candidates to speak directly to the needs of their constituents, fostering a more responsive and representative democracy. Yet, it also requires careful strategy to maintain party cohesion and credibility. By mastering this balance, candidates can build campaigns that are both locally resonant and nationally aligned, proving that decentralization can be a strength rather than a weakness.

Which Political Party Dominated the Southern States' Presidency?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

American political parties are decentralized because they lack a strong, centralized authority or hierarchy. Power is distributed across state and local party organizations, allowing them to operate independently with significant autonomy.

Decentralization means that decision-making is often fragmented, with state and local party leaders having considerable influence over candidate selection, policy priorities, and campaign strategies, rather than a single national leadership dictating these decisions.

Federalism contributes to decentralization by dividing political power between the federal government and state governments. This structure allows state parties to adapt to local political landscapes and operate with independence from the national party apparatus.