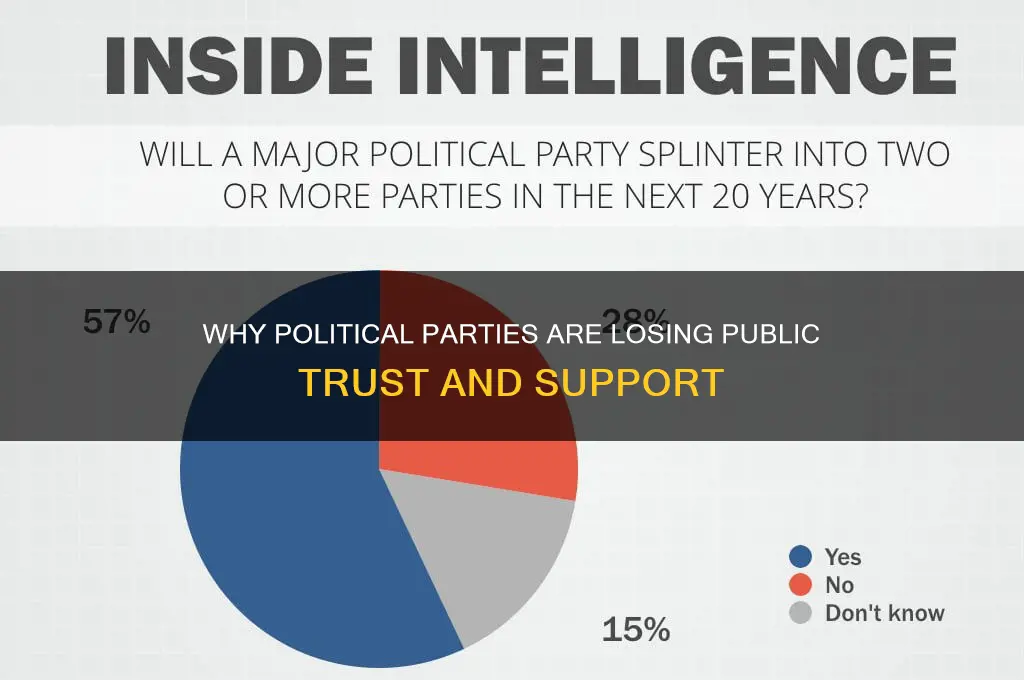

Political parties, once seen as essential pillars of democratic governance, are increasingly viewed with skepticism and distrust by the public. Rising polarization, perceived corruption, and a focus on partisan interests over public welfare have eroded their credibility. Many citizens feel that parties prioritize ideological purity and re-election campaigns over addressing pressing issues like economic inequality, climate change, and healthcare. Additionally, the influence of money in politics and the dominance of elite interests have further alienated voters, who see parties as disconnected from their everyday struggles. As a result, disillusionment with traditional party politics has fueled the rise of independent candidates, protest movements, and calls for systemic reforms to restore trust in democratic institutions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Perceived Corruption | 56% of Americans believe corruption is widespread in the government (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Partisan Polarization | 90% of Republicans and 95% of Democrats say there are strong conflicts between the parties (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Lack of Trust | Only 20% of Americans trust the government to do what is right (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Ineffective Governance | 65% of Americans believe the government is not addressing the nation's problems effectively (Gallup, 2023) |

| Special Interest Influence | 77% of Americans believe elected officials care more about special interests than the people they represent (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Lack of Representation | 55% of Americans feel their political party does not represent people like them (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Negative Campaigning | 74% of Americans believe negative campaigning is a major problem in politics (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Gridlock and Inaction | 68% of Americans are frustrated with the lack of progress on important issues due to political gridlock (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Disconnect from Reality | 63% of Americans believe politicians are out of touch with the concerns of ordinary citizens (Gallup, 2023) |

| Declining Civic Engagement | Only 57% of eligible voters participated in the 2020 US presidential election (United States Elections Project) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Voter Distrust: Scandals, broken promises, and corruption erode public trust in political parties

- Polarization: Extreme ideologies alienate moderate voters, reducing party appeal

- Lack of Representation: Parties often fail to address diverse voter needs effectively

- Focus on Power: Prioritizing winning elections over solving real issues disappoints citizens

- Negative Campaigning: Attack ads and mudslinging turn voters off from politics

Voter Distrust: Scandals, broken promises, and corruption erode public trust in political parties

Political scandals have become a recurring spectacle, leaving voters jaded and skeptical. From the Watergate scandal in the 1970s to more recent controversies like the 2016 U.S. presidential election interference, these events dominate headlines and shape public perception. Each revelation of misconduct, whether it’s misuse of funds, unethical behavior, or illegal activities, chips away at the credibility of political parties. For instance, the 2019 "Cash for Honors" scandal in the UK, where political donors were allegedly offered peerages, further deepened public cynicism. Such incidents create a narrative of systemic corruption, making it difficult for parties to regain trust.

Broken promises are another significant contributor to voter distrust. Campaigns often feature lofty pledges—universal healthcare, tax cuts, or environmental reforms—that resonate with voters. However, once in power, many of these promises remain unfulfilled. A 2021 study by the Pew Research Center found that 72% of Americans believe elected officials care more about special interests than the people they represent. For example, the repeated failure to address gun control in the U.S. despite widespread public support has alienated many voters. This pattern of unmet expectations breeds disillusionment, as citizens feel their voices are ignored in favor of political expediency.

Corruption, both perceived and proven, further exacerbates the erosion of trust. Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked several countries with declining scores, citing political party financing and lobbying as key issues. In Brazil, the Lava Jato (Car Wash) scandal exposed a vast network of bribery and money laundering involving major political figures, leading to widespread protests. Similarly, in South Africa, the state capture scandal under Jacob Zuma’s presidency undermined public faith in the ANC. These cases highlight how corruption not only damages individual parties but also tarnishes the entire political system, making voters question the integrity of their leaders.

To rebuild trust, political parties must take concrete steps toward transparency and accountability. Implementing stricter campaign finance regulations, such as capping donations and requiring real-time disclosure, can reduce the influence of special interests. Parties should also adopt mechanisms for holding leaders accountable for broken promises, such as public tracking of campaign pledges and independent audits. For instance, New Zealand’s introduction of a "Promise Tracker" during elections has set a precedent for transparency. Additionally, fostering a culture of integrity through ethics training and whistleblower protections can help restore voter confidence. Without such measures, the cycle of distrust will persist, further alienating citizens from the political process.

Chad Bianco's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Registered Party

You may want to see also

Polarization: Extreme ideologies alienate moderate voters, reducing party appeal

Political polarization has become a defining feature of modern democracies, with parties increasingly adopting extreme ideologies to solidify their bases. This shift alienates moderate voters, who find themselves without a political home. Consider the United States, where the Democratic and Republican parties have moved further apart on issues like healthcare, climate change, and immigration. A 2021 Pew Research Center study found that 73% of Americans believe the divide between the two parties is wider than ever, with moderates feeling marginalized by the lack of compromise and centrism. This trend is not unique to the U.S.; countries like Brazil, India, and the UK have seen similar patterns, where radicalized rhetoric dominates, leaving pragmatists disillusioned.

To understand the impact, imagine a moderate voter in a swing district. They prioritize affordable housing, education reform, and environmental sustainability but are met with party platforms that emphasize defunding the police or abolishing ICE on one side, and denying climate science or slashing social programs on the other. These extremes force moderates into a corner, often leading to apathy or protest votes. For instance, in the 2020 U.S. election, nearly 10% of voters identified as moderate but felt compelled to choose the "lesser of two evils," according to exit polls. This dynamic reduces party appeal, as moderates perceive parties as more interested in ideological purity than in addressing their concerns.

Parties can reverse this trend by adopting a three-step strategy. First, prioritize policy over purity by crafting platforms that appeal to a broader spectrum of voters. For example, instead of advocating for universal healthcare or its complete abolition, parties could propose incremental reforms like expanding Medicaid or introducing public options. Second, amplify moderate voices within the party structure. In France, President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist movement, La République En Marche!, gained traction by explicitly rejecting extremes and focusing on pragmatic solutions. Third, engage in cross-party collaborations on non-partisan issues. In Germany, the coalition government between the center-right CDU and center-left SPD demonstrates how compromise can appeal to moderates, even if it frustrates ideological purists.

However, this approach comes with cautions. Parties risk backlash from their bases if they appear to "sell out" core principles. For instance, the UK Labour Party’s shift toward centrism under Tony Blair alienated its left wing, while its return to socialism under Jeremy Corbyn drove away moderates. Balancing inclusivity and identity is critical. Parties must communicate that moderation is not weakness but a commitment to governance over ideology. Practical tips include conducting focus groups with moderate voters to identify shared priorities and using data analytics to tailor messaging without alienating core supporters.

In conclusion, polarization’s grip on political parties is self-perpetuating: extremes drive away moderates, who then have less influence, allowing extremes to dominate further. Breaking this cycle requires intentionality. Parties must recognize that moderate voters are not ideologically neutral but pragmatic, seeking solutions over slogans. By recalibrating their strategies, parties can reclaim their appeal and restore faith in democratic institutions. The alternative—continued alienation of moderates—risks deepening political fragmentation and eroding public trust.

Eric Greitens' Political Affiliation: Which Party Claims the Former Governor?

You may want to see also

Lack of Representation: Parties often fail to address diverse voter needs effectively

Political parties, once seen as the backbone of democratic representation, are increasingly viewed as out of touch with the diverse needs of their constituents. A glaring example is the urban-rural divide, where policies favoring metropolitan areas often overshadow the concerns of rural communities. For instance, while urban voters might prioritize public transportation and affordable housing, rural voters may focus on agricultural subsidies and broadband access. When parties fail to balance these competing interests, they alienate significant portions of their electorate, fostering resentment and disengagement.

Consider the demographic shifts reshaping electorates worldwide. Aging populations in countries like Japan and Germany demand policies addressing pension reforms and healthcare, while younger voters in nations such as India and Nigeria prioritize education and job creation. Parties that adopt a one-size-fits-all approach risk neglecting these distinct needs. A 2021 Pew Research Center study found that 64% of millennials and Gen Z voters in the U.S. feel political parties do not represent their views, compared to 52% of Baby Boomers. This generational gap underscores the failure of parties to adapt their platforms to evolving voter priorities.

The issue extends beyond age and geography to encompass identity and ideology. Marginalized groups, including racial minorities, LGBTQ+ communities, and immigrants, often find their concerns sidelined in favor of majority interests. For example, in the U.S., the Black Lives Matter movement highlighted systemic racism, yet many political parties have struggled to translate this momentum into concrete policy changes. Similarly, in Europe, the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment has left many migrant communities feeling politically invisible. Parties that fail to address these disparities risk perpetuating inequality and eroding trust.

To bridge this representation gap, parties must adopt a more granular approach to policy-making. This involves conducting localized surveys, holding town hall meetings, and leveraging data analytics to identify specific voter needs. For instance, a party in a diverse district might use polling data to craft targeted policies, such as bilingual education programs or small business grants for minority entrepreneurs. Additionally, parties should prioritize internal diversity, ensuring their leadership and candidate pools reflect the communities they aim to represent.

Ultimately, the lack of representation is not just a symptom of political unpopularity but a root cause. Parties that fail to address diverse voter needs effectively risk becoming relics of a bygone era, unable to inspire loyalty or mobilize support. By embracing inclusivity and adaptability, they can rebuild trust and reclaim their role as champions of the people’s voice.

Political Parties' Impact on Government Regulation: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Focus on Power: Prioritizing winning elections over solving real issues disappoints citizens

Political parties often behave like sports teams, fixated on securing victory rather than addressing the root causes of societal problems. This win-at-all-costs mentality manifests in several ways: candidates tailor messages to appeal to narrow demographics, campaigns prioritize fundraising over policy development, and elected officials spend more time strategizing for reelection than governing effectively. For instance, a study by the Pew Research Center found that 74% of Americans believe politicians care more about winning elections than serving the public interest. This disconnect erodes trust and leaves citizens feeling like mere spectators in a game they never signed up to play.

Consider the issue of healthcare reform. Instead of collaborating on a bipartisan solution to reduce costs and improve access, parties often use the issue as a political football. One party might propose incremental changes to avoid alienating donors, while the other obstructs progress to deny their opponents a legislative win. Meanwhile, millions of citizens struggle with unaffordable premiums and limited coverage. This pattern repeats across issues like climate change, education, and infrastructure, where long-term solutions are sacrificed for short-term political gains. The result? A disillusioned electorate that views political parties as obstacles rather than advocates.

To break this cycle, parties must adopt a results-oriented mindset. Here’s a practical roadmap: First, establish independent commissions to draft policy solutions, insulating the process from partisan interference. Second, implement term limits to reduce the pressure of perpetual campaigning. Third, incentivize bipartisanship by rewarding legislators for co-sponsoring bills across party lines. For example, New Zealand’s mixed-member proportional system encourages collaboration by requiring parties to form coalitions, leading to more pragmatic governance. While these steps won’t eliminate political competition, they can shift the focus from winning elections to delivering outcomes that matter to citizens.

Critics may argue that such reforms are idealistic and difficult to implement. However, the alternative—a political system paralyzed by partisanship—is unsustainable. Take the case of Belgium, which went 541 days without a government in 2010-2011 due to political gridlock. While Belgium’s situation was extreme, it serves as a cautionary tale for any democracy prioritizing power over progress. By refocusing on problem-solving, political parties can rebuild trust and demonstrate that governance is about more than just winning the next election.

Unveiling MTG Politics: Understanding the Movement and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Negative Campaigning: Attack ads and mudslinging turn voters off from politics

Political campaigns have increasingly become battlegrounds for personal attacks and mudslinging, a strategy that, while effective in grabbing attention, often leaves a sour taste in voters' mouths. This phenomenon is not new, but its prevalence in modern politics has reached a point where it significantly contributes to the growing unpopularity of political parties. The constant barrage of negative ads and smear campaigns not only fails to inform voters about policies but also fosters a toxic environment that repels potential supporters.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where attack ads dominated the airwaves. According to the Wesleyan Media Project, 70% of all political ads aired during the campaign were negative, focusing on personal flaws and scandals rather than policy proposals. This approach may have succeeded in mobilizing hardcore partisans, but it alienated undecided voters and independents, many of whom felt disgusted by the tone of the campaign. A Pew Research Center survey found that 59% of voters were bothered "a lot" by the tone of the election, a sentiment that likely contributed to the historically low favorability ratings of both major candidates.

The problem with negative campaigning lies in its psychological impact on voters. Research in political psychology shows that attack ads, while memorable, often backfire by creating a sense of political fatigue and cynicism. When voters are constantly exposed to messages that portray candidates as untrustworthy or corrupt, they begin to generalize this negativity to the entire political system. This erosion of trust is particularly damaging among younger voters, who are already less engaged with traditional politics. For instance, a study by the Knight Foundation found that 44% of millennials believe that "politics has become too nasty" and is a major reason for their disengagement.

To counteract this trend, political parties must rethink their campaign strategies. Instead of relying on mudslinging, they should focus on constructive messaging that highlights their vision and policy solutions. Practical steps include setting internal guidelines to limit negative ads, investing in positive storytelling, and engaging voters through grassroots efforts rather than expensive media campaigns. Parties could also adopt a "clean campaign pledge," as seen in some European countries, where candidates commit to avoiding personal attacks. While this may seem idealistic, it could help restore voter trust and differentiate a party as a principled alternative.

Ultimately, the takeaway is clear: negative campaigning may yield short-term gains, but its long-term consequences are deeply corrosive. By prioritizing substance over smears, political parties can begin to rebuild their reputation and re-engage a disillusioned electorate. The challenge lies in breaking the cycle of negativity, but the potential rewards—increased voter turnout, greater public trust, and a healthier political discourse—are well worth the effort.

Theodore Roosevelt's Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties often become unpopular due to perceived corruption, lack of transparency, and failure to address voters' needs. Additionally, partisan polarization and gridlock can alienate voters who seek compromise and effective governance.

The heavy reliance on fundraising, often from wealthy donors or special interests, creates the perception that parties prioritize the agendas of the elite over the concerns of ordinary citizens, eroding public trust.

Many voters feel that political parties are out of touch with their daily struggles and focus more on ideological purity or winning elections than on practical solutions to real-world problems.

Yes, in systems dominated by two major parties, voters often feel limited in their choices, leading to frustration. This lack of diversity in representation can make parties seem unresponsive to diverse viewpoints.