Political parties emerged as essential structures in democratic societies to organize and mobilize diverse interests, ideas, and groups within a population. Their development was driven by the need to aggregate and represent the voices of citizens in complex political systems, ensuring that governance reflected the will of the people. Historically, parties evolved from informal factions and alliances into formalized institutions during the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly in response to the expansion of suffrage and the rise of mass politics. They provided a framework for like-minded individuals to unite around shared ideologies, policies, and goals, facilitating collective action and competition for political power. The process of party formation often involved the consolidation of regional, economic, or social interests, as well as the creation of mechanisms for candidate selection, fundraising, and voter outreach. Over time, parties became central to democratic processes, shaping public discourse, structuring elections, and serving as intermediaries between the state and its citizens. Their development reflects the broader evolution of political systems toward inclusivity, representation, and the management of societal diversity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Need for Representation | Political parties emerged to represent diverse interests and ideologies in society. |

| Organizational Efficiency | Parties developed as structured organizations to mobilize resources and coordinate political activities. |

| Electoral Competition | They arose to compete in elections, providing voters with clear choices and platforms. |

| Ideological Cohesion | Parties formed around shared beliefs, values, and policy goals to unite like-minded individuals. |

| Power Consolidation | They developed to gain and maintain political power through collective action and strategy. |

| Voter Mobilization | Parties evolved to engage and mobilize voters through campaigns, rallies, and outreach. |

| Policy Formulation | They became platforms for developing and advocating specific policies and agendas. |

| Conflict Resolution | Parties emerged as mechanisms to manage and resolve political conflicts through negotiation and compromise. |

| Social Integration | They facilitated the integration of diverse groups into the political process. |

| Adaptation to Democracy | Parties developed as essential components of democratic systems to ensure pluralism and representation. |

| Resource Pooling | They enabled the pooling of financial, human, and intellectual resources for political campaigns. |

| Accountability Mechanisms | Parties evolved to hold elected officials accountable to their constituents and party platforms. |

| Historical Context | Their development was influenced by historical events, societal changes, and the evolution of governance. |

| Technological Advancements | Modern parties utilize technology for communication, fundraising, and voter targeting. |

| Globalization Influence | Global trends and international politics have shaped the development and strategies of political parties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of political parties

The roots of political parties can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where factions and alliances formed around influential leaders or ideologies. In Rome, for instance, the Optimates and Populares emerged as early precursors to political parties, representing the interests of the aristocracy and the common people, respectively. These groups laid the groundwork for organized political competition, demonstrating that the struggle for power and influence is as old as governance itself.

The formal development of political parties, however, gained momentum during the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in England and the United States. The English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 fostered the rise of the Whigs and Tories, groups that coalesced around differing views on monarchy, religion, and governance. These factions were not yet modern political parties but served as prototypes, illustrating how shared interests and ideologies could unite individuals into cohesive blocs. Similarly, in the American colonies, the Federalist and Anti-Federalist movements emerged during the debate over the U.S. Constitution, highlighting the role of political parties in shaping national identity and policy.

The industrialization and democratization of the 19th century further accelerated the evolution of political parties. As suffrage expanded and mass politics took hold, parties became essential tools for mobilizing voters and aggregating interests. In Europe, parties like the British Conservatives and Liberals institutionalized their roles in parliamentary systems, while in the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties solidified their dominance. This period also saw the rise of socialist and labor parties, reflecting the growing influence of working-class movements and the need for representation beyond traditional elites.

A comparative analysis reveals that political parties often emerge in response to societal divisions and the need for organized representation. Whether driven by class conflict, regional differences, or ideological disputes, parties provide a mechanism for channeling diverse interests into the political process. For example, the Indian National Congress formed in 1885 as a platform for Indian independence, while the African National Congress in South Africa emerged to combat apartheid. These examples underscore the adaptability of political parties to address specific historical contexts and challenges.

In conclusion, the historical origins of political parties reflect a universal human tendency to organize around shared goals and interests. From ancient factions to modern institutions, parties have evolved as essential instruments of democracy, facilitating governance, representation, and political participation. Understanding their origins offers valuable insights into their enduring role in shaping societies and resolving conflicts.

Exploring Luxembourg's Political Landscape: A Look at Its Numerous Parties

You may want to see also

Social and economic factors driving party formation

The emergence of political parties is often a response to the complex interplay of social and economic forces within a society. One key driver is the stratification of wealth and resources, which creates distinct interest groups vying for representation. In agrarian societies, for example, landowning elites formed parties to protect their property rights, while emerging industrialists sought political vehicles to advocate for free trade and deregulation. This dynamic is evident in 19th-century Britain, where the Tory and Whig parties evolved to represent the interests of the aristocracy and the rising middle class, respectively. As economies diversify, so do the factions seeking political influence, leading to the proliferation of parties along socioeconomic lines.

Urbanization plays a pivotal role in party formation by concentrating populations and fostering shared grievances or aspirations. Cities become melting pots of ideas, where workers, intellectuals, and entrepreneurs interact, often leading to the crystallization of political movements. The rise of labor parties in industrialized nations, such as the German Social Democratic Party in the late 1800s, exemplifies this trend. Urban centers provided the organizational infrastructure—unions, newspapers, and public spaces—necessary for mobilizing mass support. Conversely, rural populations may form parties to counterbalance urban dominance, as seen in agrarian parties across Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Economic inequality acts as a catalyst for party formation by creating a sense of injustice among marginalized groups. When wealth disparities become extreme, those excluded from economic opportunities often turn to politics as a means of redress. The Great Depression, for instance, fueled the growth of socialist and communist parties worldwide, as they offered radical solutions to systemic poverty. Similarly, in contemporary societies, movements like Occupy Wall Street and the rise of left-wing parties in Europe reflect a backlash against neoliberal policies that exacerbate inequality. Parties emerge as vehicles for channeling economic discontent into political action.

Social identity intersects with economic factors to shape party formation, particularly in diverse societies. Ethnic, religious, or regional groups often coalesce into political parties to safeguard their unique interests. In India, for example, caste-based parties like the Bahujan Samaj Party represent the political aspirations of lower castes excluded from economic and social power. Similarly, in Africa, ethnic-based parties frequently dominate political landscapes, reflecting historical divisions and resource competition. These parties serve as both economic advocates and cultural guardians, highlighting the inseparable link between material conditions and identity politics.

Understanding these social and economic drivers is crucial for predicting party formation in evolving societies. Practical steps for analyzing potential party emergence include mapping wealth distribution, tracking urbanization rates, and monitoring inequality indices. Policymakers and scholars alike can use these metrics to identify groups likely to mobilize politically. For instance, a sudden influx of foreign investment in a region might spur the formation of nationalist parties wary of economic exploitation. By recognizing these patterns, stakeholders can anticipate political shifts and foster more inclusive governance structures. The interplay of social and economic forces is not just a historical phenomenon but a living process shaping the political landscape today.

The Impeachment of President Clinton: Which Party Led the Charge?

You may want to see also

Role of ideology in party development

Ideology serves as the backbone of political parties, providing a coherent framework that unites members, attracts supporters, and guides policy decisions. Without a shared ideological core, parties risk becoming mere coalitions of individual interests, lacking the stability and purpose needed to endure. For instance, the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States are often defined by their ideological stances—liberalism and conservatism, respectively—which shape their platforms, voter bases, and legislative priorities. This ideological grounding is not unique to modern democracies; even in the early days of party formation, such as the Whigs and Tories in 18th-century Britain, competing visions of governance and society drove party development.

Consider the process of party formation as a recipe: ideology is the essential ingredient that binds disparate elements into a cohesive whole. First, identify a core set of principles—economic equality, individual liberty, or national identity, for example. Next, articulate these principles into a clear, actionable platform that resonates with potential supporters. Caution: avoid overloading the platform with contradictory ideas, as this dilutes the party’s identity and confuses voters. Finally, consistently communicate this ideology through speeches, campaigns, and policy actions to reinforce the party’s brand. Practical tip: use social media and grassroots organizing to amplify ideological messages, ensuring they reach diverse demographics effectively.

The role of ideology in party development is not static; it evolves in response to societal changes, crises, and shifting voter priorities. For example, the rise of Green parties across Europe reflects a growing ideological focus on environmental sustainability and climate action. Similarly, the emergence of populist movements in recent years highlights how ideologies can adapt to exploit economic anxieties and cultural grievances. Parties that fail to update their ideologies risk becoming irrelevant, as seen with traditional socialist parties struggling to compete with newer left-wing movements. To stay relevant, parties must periodically reassess their ideological foundations, balancing core principles with contemporary concerns.

A comparative analysis reveals that ideology’s impact on party development varies across political systems. In two-party systems like the U.S., ideologies tend to be broad and inclusive, allowing parties to appeal to a wide range of voters. In multiparty systems, such as those in Germany or India, ideologies are more specialized, enabling smaller parties to carve out distinct niches. However, regardless of the system, ideology remains a critical tool for differentiation. Without it, parties risk blending into a generic political landscape, making it harder to mobilize support or win elections.

In conclusion, ideology is not merely a decorative element of political parties but a functional necessity. It provides direction, fosters unity, and distinguishes parties in a crowded political field. By understanding the role of ideology in party development, one can better navigate the complexities of political systems and appreciate how ideas shape the course of governance. Whether building a new party or revitalizing an existing one, prioritizing a clear and compelling ideology is a strategic imperative.

Understanding Political Party Values: The Role of Party Platforms and Manifestos

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Influence of electoral systems on party structures

Electoral systems act as the architectural blueprints of political landscapes, shaping not only how votes are cast but also how parties organize and operate. Consider the contrast between proportional representation (PR) and first-past-the-post (FPTP) systems. In PR systems, like those in the Netherlands or Israel, parties win seats in proportion to their vote share. This encourages the emergence of niche parties catering to specific ideologies or demographics, as even small vote percentages translate into parliamentary representation. Conversely, FPTP systems, as seen in the UK or the US, reward parties that can secure a plurality of votes in individual districts, fostering a two-party dominance where smaller parties struggle to gain traction unless they consolidate into broader coalitions.

The mechanics of electoral systems also dictate party strategies and internal structures. In mixed-member proportional (MMP) systems, such as Germany’s, parties must balance national appeal with local candidate strength, often leading to dual-track leadership structures. National leaders focus on policy and branding, while local candidates build grassroots support. This hybrid approach contrasts sharply with the centralized, top-down structures common in majoritarian systems, where parties prioritize national messaging and resource allocation to swing districts. For instance, the Conservative Party in the UK operates with a highly centralized command structure, reflecting the need to win key marginal seats under FPTP.

A critical yet overlooked aspect is the threshold requirement in PR systems, which can dramatically alter party behavior. In Turkey, for example, a 10% national vote threshold forces smaller parties to either merge or risk irrelevance, leading to strategic alliances like the Nation Alliance in 2018. Conversely, systems with low or no thresholds, such as the Netherlands, allow for a proliferation of small parties, fragmenting the political landscape. Parties in such systems often invest heavily in niche policy development and targeted voter outreach to differentiate themselves in a crowded field.

Finally, the interplay between electoral systems and party structures has practical implications for governance. Multi-party systems born out of PR often lead to coalition governments, necessitating parties to develop negotiation skills and compromise-oriented platforms. This can result in more inclusive policies but also slower decision-making. In contrast, FPTP systems tend to produce single-party majorities, enabling quicker legislative action but at the risk of marginalizing minority voices. For instance, New Zealand’s shift from FPTP to MMP in 1996 transformed its political ecosystem, increasing representation for smaller parties like the Greens and Māori Party but also leading to more frequent coalition-building challenges.

In essence, electoral systems are not neutral mechanisms but powerful forces that mold party structures, strategies, and outcomes. Understanding this relationship is crucial for anyone seeking to navigate or reform political systems. Whether designing a new system or operating within an existing one, the choice of electoral rules will determine not just who wins but how parties evolve, compete, and govern.

President Wilson's Political Affiliation: Unveiling His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Evolution of parties in democratic vs. authoritarian regimes

Political parties evolve differently in democratic and authoritarian regimes, shaped by the distinct structures and incentives of each system. In democracies, parties emerge as vehicles for aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and competing for power through elections. Their development is driven by the need to represent diverse ideologies, foster public engagement, and ensure accountability. For instance, the two-party system in the United States and the multi-party systems in India or Germany illustrate how democratic institutions encourage parties to adapt to voter preferences and societal changes. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often create or co-opt parties to consolidate power, suppress opposition, and maintain control. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) exemplifies this, serving as the regime’s backbone rather than a competitive entity. Here, parties are tools of governance, not platforms for political contestation.

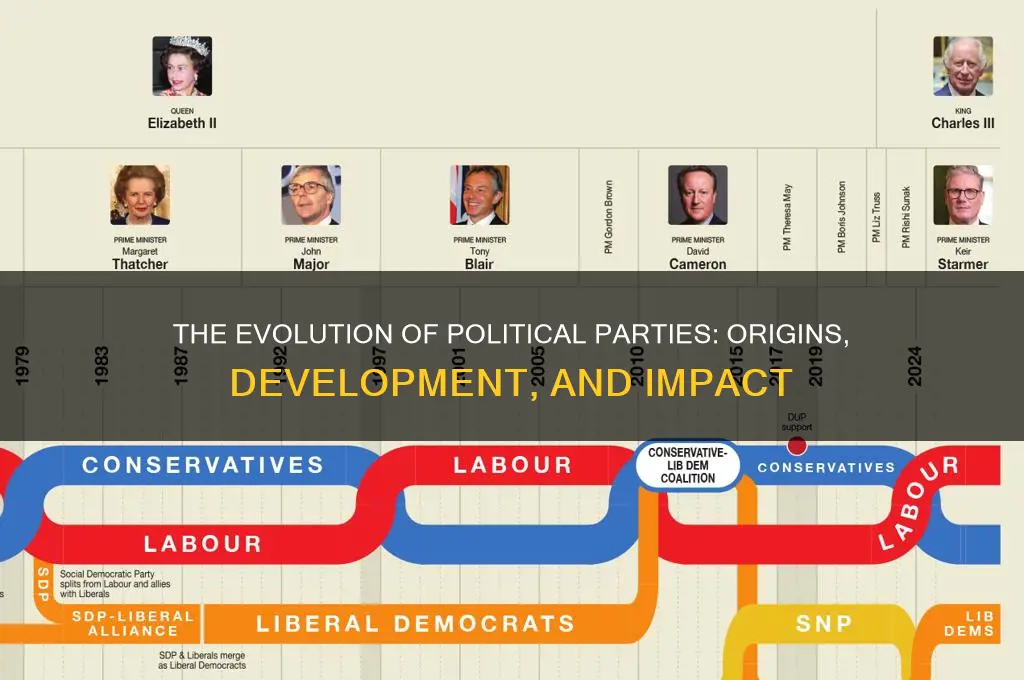

Consider the lifecycle of a political party in these contrasting environments. In democracies, parties rise and fall based on their ability to respond to public demands, manage internal factions, and win elections. This dynamic process ensures renewal and adaptability. For example, the Labour Party in the UK shifted from socialist roots to a more centrist stance under Tony Blair to broaden its appeal. In authoritarian systems, parties are often static, prioritizing regime survival over ideological evolution. The longevity of the CCP, for instance, is tied to its ability to suppress dissent and co-opt elites, not to electoral performance. This rigidity limits their capacity to address societal grievances, often leading to stagnation or crisis.

To understand the divergence, examine the role of competition. Democratic parties thrive on competition, which forces them to innovate, compromise, and remain relevant. Authoritarian parties, however, operate in a controlled environment where competition is either eliminated or tightly managed. In Russia, United Russia functions as a dominant party, sidelining opposition through legal and extralegal means. This lack of genuine competition stifles political development, making authoritarian parties less responsive to societal needs. The takeaway is clear: competition is the lifeblood of democratic parties, while authoritarian parties rely on suppression and control.

Practical implications arise from these differences. In democracies, parties must invest in grassroots organization, policy development, and voter outreach to succeed. This requires resources, strategic planning, and a dose of pragmatism. For instance, campaigns in the U.S. often cost billions, reflecting the intensity of competition. In authoritarian regimes, parties focus on maintaining loyalty, monitoring dissent, and distributing patronage. The CCP’s mass surveillance and cadre system exemplify this approach. For activists or policymakers, understanding these dynamics is crucial: democratic parties need support for institutional strengthening, while authoritarian parties require external pressure to open political space.

Ultimately, the evolution of parties in democratic versus authoritarian regimes highlights a fundamental trade-off between responsiveness and stability. Democratic parties are messy, unpredictable, and often inefficient, but they ensure representation and accountability. Authoritarian parties offer stability and control but at the cost of suppressing dissent and stifling innovation. This distinction is not just academic—it shapes governance, policy, and societal outcomes. Whether building a party or analyzing political systems, recognizing these differences is essential for effective strategy and meaningful change.

Condoleezza Rice's Political Party Affiliation: Unraveling Her Political Identity

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties developed to organize and mobilize voters around shared ideologies, interests, and policy goals. They provide a structured way for citizens to participate in politics, influence government decisions, and hold leaders accountable.

Early political parties in the U.S., such as the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, emerged in the late 18th century due to differing views on the role of the federal government, economic policies, and the interpretation of the Constitution. These divisions led to the creation of organized factions to advocate for their respective agendas.

In modern democracies, political parties serve as intermediaries between the government and the public. They recruit candidates, develop policy platforms, coordinate campaigns, and ensure representation of diverse viewpoints in the political process.

Political parties evolve in response to changing societal values, demographic shifts, and new political issues. They may adapt their platforms, merge with other groups, or split into factions to remain relevant and competitive in the political landscape.