The question of who was the first president from a political party is a significant one in American history, as it marks the emergence of organized political factions in the United States. While George Washington, the nation's first president, intentionally remained unaffiliated with any political party to maintain unity, his successors quickly became entangled in the growing partisan divide. The first president to be formally associated with a political party was Thomas Jefferson, who was elected in 1800 as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party. This party, which Jefferson co-founded with James Madison and others, opposed the Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. Jefferson's victory not only solidified the role of political parties in American politics but also marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties, setting a precedent for the democratic process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | George Washington |

| Political Party | None (independent, but aligned with Federalist principles) |

| Term in Office | April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 |

| First President | Yes, first President of the United States |

| Political Party Formation | Washington did not formally belong to a political party during his presidency. The first political parties (Federalists and Democratic-Republicans) emerged during his administration. |

| Key Achievements | Established the Cabinet system, set precedents for the presidency, and maintained neutrality in foreign affairs. |

| Stance on Parties | Warned against the dangers of political factions in his Farewell Address. |

| Successor | John Adams (Federalist Party) |

| Historical Context | Washington's presidency laid the foundation for the two-party system in the U.S. |

Explore related products

$9.99

What You'll Learn

- George Washington’s Nonpartisanship: Washington opposed political factions, refusing to align with any party during his presidency

- Emergence of Federalists: Led by Alexander Hamilton, Federalists formed the first organized political party in the U.S

- Democratic-Republicans Rise: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison founded the Democratic-Republican Party in opposition to Federalists

- John Adams’ Presidency: Adams, a Federalist, became the first president affiliated with a political party in 1797

- Two-Party System Begins: The rivalry between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans established the U.S. two-party system

George Washington’s Nonpartisanship: Washington opposed political factions, refusing to align with any party during his presidency

George Washington, the first President of the United States, stands as a singular figure in American political history due to his steadfast refusal to align with any political party during his presidency. While his successors would become deeply entrenched in the emerging two-party system, Washington remained an independent voice, viewing partisanship as a threat to the young nation’s unity. This nonpartisanship was not merely a personal preference but a deliberate stance rooted in his belief that factions would undermine the stability and effectiveness of the federal government. His Farewell Address of 1796 explicitly warned against the dangers of party divisions, urging Americans to prioritize the common good over partisan interests.

Washington’s opposition to political factions was shaped by his experiences during the Revolutionary War and the Constitutional Convention. He witnessed firsthand how divisions among the colonies could weaken collective efforts, and he carried this lesson into his presidency. By refusing to affiliate with either the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, or the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, Washington sought to model impartial leadership. His cabinet, for instance, included members from both ideological camps, a deliberate attempt to foster collaboration rather than competition. This approach, though criticized by some as indecisive, was a strategic effort to prevent the hardening of partisan lines.

The practical implications of Washington’s nonpartisanship are evident in his handling of key issues during his presidency. For example, while he supported Hamilton’s financial policies, such as the establishment of a national bank, he did not publicly endorse the Federalist Party. Similarly, he maintained cordial relations with Jefferson despite their ideological differences. This balanced approach allowed him to navigate contentious debates without alienating either side, preserving his authority as a unifying figure. His ability to rise above party politics set a precedent for presidential leadership, though it was rarely emulated by his successors.

Critics argue that Washington’s nonpartisanship was unsustainable in a rapidly polarizing political landscape. By the end of his second term, the divisions between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans were already deepening, and his warnings against factions seemed increasingly idealistic. However, his stance remains a valuable historical example of the potential dangers of unchecked partisanship. In today’s hyper-partisan environment, Washington’s commitment to national unity over party loyalty offers a timely reminder of the importance of compromise and collaboration in governance.

To emulate Washington’s nonpartisan principles in modern politics, leaders and citizens alike can take specific steps. First, prioritize issues over ideology by evaluating policies on their merits rather than their partisan origins. Second, foster dialogue across party lines by engaging with diverse perspectives and avoiding echo chambers. Finally, hold elected officials accountable for their actions, not their party affiliations. While complete nonpartisanship may be unattainable in a multiparty system, Washington’s example encourages a more thoughtful and inclusive approach to political participation. His legacy challenges us to ask: Can we rise above party divisions to serve the greater good?

Thomas Jefferson's Stance on Political Parties: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Emergence of Federalists: Led by Alexander Hamilton, Federalists formed the first organized political party in the U.S

The Federalist Party, emerging in the late 18th century, marked a pivotal shift in American politics by becoming the nation’s first organized political party. Led by Alexander Hamilton, the Federalists coalesced around a shared vision of a strong central government, economic modernization, and alignment with Britain. Their formation was not merely a reaction to ideological differences but a strategic move to consolidate power and shape the young republic’s future. Hamilton’s influence as Secretary of the Treasury and his ability to mobilize supporters through newspapers and legislative alliances were instrumental in the party’s rise. This period laid the groundwork for partisan politics in the U.S., transforming how policies were debated and implemented.

To understand the Federalists’ emergence, consider their response to the economic chaos of the post-Revolutionary era. Hamilton’s financial plan, which included assuming state debts, establishing a national bank, and promoting manufacturing, became the party’s cornerstone. These policies were not just economic strategies but ideological statements. By advocating for a centralized financial system, the Federalists positioned themselves as the party of stability and progress, appealing to merchants, urban elites, and those who feared the fragility of state-based governance. Their ability to translate abstract ideas into actionable policies set a precedent for future political parties.

Contrast the Federalists with their rivals, the Democratic-Republicans led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. While the Federalists championed industrialization and close ties with Britain, their opponents favored agrarianism and alignment with France. This ideological divide was not merely about policy but also about the soul of the nation. The Federalists’ emphasis on order and authority often clashed with the Democratic-Republicans’ vision of decentralized power and individual liberty. Yet, it was this tension that defined early American politics, forcing both parties to articulate clear platforms and engage in vigorous public debate.

A practical takeaway from the Federalists’ emergence is the importance of organizational structure in politics. Hamilton’s use of newspapers like *The Gazette of the United States* to disseminate Federalist ideas and coordinate supporters was revolutionary. Modern political campaigns still rely on media and grassroots organization, echoing the strategies pioneered by the Federalists. For anyone studying political movements, examining how the Federalists built a national network from scratch offers valuable lessons in coalition-building and message discipline.

Despite their eventual decline after the War of 1812, the Federalists’ legacy endures in the framework they established for American political parties. Their emphasis on a strong federal government, economic development, and international engagement continues to influence conservative thought. By studying their rise, we gain insight into how ideological coherence, strategic leadership, and effective communication can shape a nation’s political landscape. The Federalists were not just the first organized party; they were the architects of a system that remains central to American democracy.

Understanding the Role and Impact of US Political Parties

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republicans Rise: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison founded the Democratic-Republican Party in opposition to Federalists

The first U.S. president to emerge from a political party was George Washington, though he famously warned against the dangers of partisanship in his farewell address. However, the true rise of political parties began with the opposition to his administration’s policies, particularly those championed by Alexander Hamilton. This tension culminated in the formation of the Democratic-Republican Party by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, a direct response to the Federalist Party’s dominance. Their party’s creation marked the beginning of America’s two-party system, reshaping the nation’s political landscape.

Jefferson and Madison’s Democratic-Republican Party was rooted in a vision of limited federal government, states’ rights, and agrarian interests. They opposed the Federalists’ centralizing tendencies, exemplified by Hamilton’s financial policies, such as the national bank and assumption of state debts. The party’s rise was fueled by widespread discontent among farmers and rural voters, who felt marginalized by Federalist policies favoring urban merchants and industrialists. By framing their cause as a defense of republican virtues against aristocratic ambitions, Jefferson and Madison mobilized a broad coalition that would dominate American politics for decades.

The 1800 election, often called the "Revolution of 1800," was a pivotal moment for the Democratic-Republicans. Jefferson’s victory over Federalist John Adams marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties in U.S. history. This election not only solidified the party’s legitimacy but also demonstrated the power of organized political opposition. Madison’s subsequent presidency further entrenched Democratic-Republican principles, though internal divisions over issues like the War of 1812 and the national bank would eventually lead to the party’s dissolution and the rise of new factions.

To understand the Democratic-Republicans’ impact, consider their legacy in modern American politics. Their emphasis on states’ rights and skepticism of centralized authority influenced later movements, from the Jacksonian Democrats to today’s libertarian and conservative ideologies. Practical lessons from their rise include the importance of coalition-building and the strategic use of rhetoric to appeal to diverse constituencies. For instance, Jefferson’s ability to unite farmers, planters, and western settlers under a common cause remains a textbook example of effective political organizing.

In contrast to the Federalists’ elitist image, the Democratic-Republicans cultivated a populist appeal that resonated with the electorate. This approach underscores a timeless political truth: success often hinges on aligning with the aspirations and anxieties of the majority. While the party’s specific policies may seem dated, their methods—framing issues in moral terms, leveraging grassroots support, and challenging established power structures—remain relevant for anyone seeking to effect political change. The Democratic-Republicans’ rise is not just history; it’s a blueprint for political innovation.

Understanding the Political Party Division in the House of Representatives

You may want to see also

Explore related products

John Adams’ Presidency: Adams, a Federalist, became the first president affiliated with a political party in 1797

John Adams, the second President of the United States, holds a unique distinction in American political history: he was the first president to be affiliated with a political party, the Federalists, upon taking office in 1797. This marked a significant shift from the nonpartisan ideals of his predecessor, George Washington, who had warned against the dangers of political factions in his farewell address. Adams’ presidency thus became a pivotal moment in the evolution of American politics, as it formalized the role of parties in the nation’s governance.

The Federalist Party, to which Adams belonged, advocated for a strong central government, a robust financial system, and close ties with Britain. These principles were in stark contrast to those of the emerging Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, which favored states’ rights, agrarian interests, and alignment with France. Adams’ affiliation with the Federalists was not merely symbolic; it shaped his policies and decisions, particularly during a time of intense political polarization. For instance, his signing of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798, which restricted immigration and curtailed criticism of the government, was a direct reflection of Federalist priorities but also fueled opposition and accusations of tyranny.

Adams’ presidency also highlighted the challenges of governing within a partisan framework. While his Federalist affiliation provided a clear ideological direction, it also limited his ability to build consensus across party lines. This was evident in his strained relationship with Jefferson, his vice president and leader of the opposing party, which underscored the growing divide in American politics. Adams’ struggle to balance party loyalty with national unity offers a cautionary tale about the complexities of partisan governance.

Despite these challenges, Adams’ tenure as the first partisan president laid the groundwork for the two-party system that continues to dominate American politics. His presidency demonstrated that political parties could serve as vehicles for organizing and mobilizing public opinion, even as they risked exacerbating divisions. For modern observers, Adams’ experience serves as a reminder that while parties can provide structure and direction, they must also be managed carefully to avoid undermining the broader interests of the nation.

In practical terms, Adams’ presidency teaches us the importance of understanding the historical roots of partisanship. For educators, policymakers, or citizens seeking to navigate today’s polarized political landscape, studying Adams’ era can provide valuable insights into the origins of party politics. By examining his decisions, successes, and failures, we can better appreciate the enduring impact of partisanship on American governance and learn how to mitigate its potential pitfalls.

Madelyn Orochena's Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

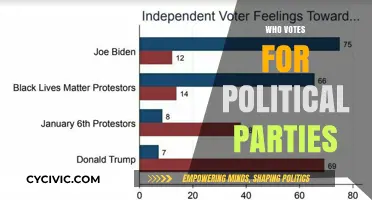

Two-Party System Begins: The rivalry between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans established the U.S. two-party system

The United States' two-party system, a cornerstone of its political landscape, was forged in the fiery rivalry between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This ideological clash not only shaped the nation's early governance but also set a precedent for the enduring dominance of two major parties. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, championed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, favored states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more democratic, decentralized government. This fundamental divide laid the groundwork for the two-party system, as each faction sought to consolidate power and influence.

To understand the mechanics of this system, consider the strategic maneuvers of these early parties. Federalists, for instance, used their control of the first federal government to pass legislation like the Alien and Sedition Acts, which aimed to suppress dissent but ultimately galvanized opposition. Democratic-Republicans, meanwhile, capitalized on grassroots support, leveraging their appeal to farmers and the common man to win key elections, including Jefferson’s victory in 1800. This period demonstrated how parties could mobilize voters, shape policy, and challenge one another’s dominance—a dynamic that remains central to American politics today.

A critical takeaway from this era is the role of elections as battlegrounds for party supremacy. The 1800 election, often called the "Revolution of 1800," marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties in U.S. history. It showcased the resilience of the two-party system, as Democratic-Republicans displaced Federalists without resorting to violence. This transition underscored the importance of institutional mechanisms, such as the Electoral College, in maintaining stability during political shifts. For modern observers, this historical example highlights the system’s ability to endure despite intense partisan conflict.

However, the two-party system’s emergence was not without cautionary tales. The Federalists’ decline, hastened by their association with elitism and their opposition to the War of 1812, illustrates the risks of alienating broad segments of the electorate. Similarly, the Democratic-Republicans’ eventual factionalism led to the rise of new parties, such as the Whigs. These lessons remind us that while the two-party system provides stability, it also demands adaptability and responsiveness to public sentiment. Parties that fail to evolve risk obsolescence, a principle as relevant today as it was two centuries ago.

In practical terms, the Federalist-Democratic-Republican rivalry offers a blueprint for understanding contemporary politics. It teaches that parties thrive by articulating distinct visions, mobilizing diverse constituencies, and navigating ideological differences. For those engaged in politics—whether as voters, activists, or candidates—this history emphasizes the importance of engagement, coalition-building, and principled debate. By studying this foundational period, we gain insights into how the two-party system operates and how it can be strengthened to address the challenges of an ever-changing nation.

Edmund Randolph's Political Party: Uncovering His Affiliation and Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Washington was the first President of the United States, but he did not belong to a political party. The first president to be affiliated with a political party was Thomas Jefferson, who was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Thomas Jefferson was a founding member of the Democratic-Republican Party, which opposed the Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams.

Political parties began to emerge in the 1790s during George Washington's presidency, with the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party being the first major parties.

George Washington warned against the dangers of political factions in his Farewell Address and chose to remain unaffiliated with any party to maintain national unity.