Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, had several political enemies during his lifetime, primarily due to his active involvement in the tumultuous political landscape of 13th-century Florence. A staunch supporter of the White Guelphs, a faction aligned with the papacy, Dante found himself in direct opposition to the Black Guelphs, who favored imperial authority. His most prominent political adversary was Corso Donati, a powerful leader of the Black Guelphs, whose influence and rivalry with Dante’s faction led to Dante’s eventual exile from Florence in 1302. This exile, orchestrated by the Black Guelphs and their allies, profoundly shaped Dante’s life and work, as he never returned to his beloved city. The bitter political feud between Dante and his enemies, particularly Corso Donati, underscores the deep divisions and personal animosities that characterized medieval Italian politics.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dante vs. Guelphs: Dante's conflict with the pro-papal Guelph faction in Florence

- White Guelph Rivalry: Opposition from the White Guelphs, including Corso Donati

- Exile by Black Guelphs: Banishment by the Black Guelphs for political allegiance

- Papal Opposition: Conflict with Pope Boniface VIII over Church-State relations

- Florence's Political Betrayal: Dante's lifelong enmity toward Florence's ruling elite

Dante vs. Guelphs: Dante's conflict with the pro-papal Guelph faction in Florence

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, was deeply entangled in the political turmoil of late 13th and early 14th century Florence. His most significant political conflict was with the Guelphs, a faction that supported the authority of the Pope over the Holy Roman Emperor. Florence, like many Italian city-states, was divided between the Guelphs and their rivals, the Ghibellines, who favored imperial power. Dante himself was initially aligned with the Guelphs but later became a staunch critic of their extreme pro-papal faction, which led to his exile and lifelong animosity toward them.

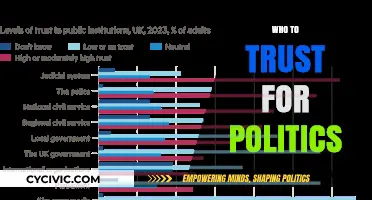

Dante's conflict with the Guelphs escalated during the 1300s, a period marked by intense political strife in Florence. The Guelph party had split into two factions: the White Guelphs and the Black Guelphs. Dante was a member of the White Guelphs, who sought a more balanced relationship with the Papacy and opposed the excessive influence of Pope Boniface VIII. The Black Guelphs, on the other hand, were radical supporters of the Pope and sought to consolidate papal power in Florence. This ideological divide set the stage for Dante's eventual downfall, as the Black Guelphs gained dominance and turned against their White counterparts.

In 1302, the Black Guelphs, backed by Pope Boniface VIII, seized control of Florence and began persecuting their political opponents. Dante, a prominent White Guelph and a prior of Florence, was accused of corruption and political conspiracy. Despite his attempts to negotiate, he was tried in absentia, fined, and sentenced to exile. If he had returned to Florence, he would have faced the harshest penalties, including being burned at the stake. This exile was a turning point in Dante's life, shaping his political and philosophical views and fueling his bitterness toward the Guelphs, particularly the Black faction and the Papacy.

Dante's works, especially *The Divine Comedy*, reflect his disdain for the Guelphs and their pro-papal policies. In the *Inferno*, he reserves a special place in Hell for corrupt politicians and religious leaders, including Pope Boniface VIII, whom he portrays as a symbol of hypocrisy and abuse of power. His critique extends beyond individuals to the systemic corruption he believed the Guelphs embodied. Dante saw their alignment with the Papacy as a betrayal of Florence's autonomy and a source of moral decay, themes he explores throughout his writing.

The conflict with the Guelphs not only defined Dante's political identity but also influenced his literary legacy. His exile forced him to wander northern Italy, seeking patronage and support, yet it also granted him the freedom to write without restraint. Dante's opposition to the Guelphs and his unwavering stance against papal interference in Florentine politics made him a symbol of resistance and intellectual integrity. His struggle against the pro-papal faction remains a testament to the enduring tension between secular and religious authority in medieval Europe.

Exploring the Diverse Political Parties Shaping Global Governance Today

You may want to see also

White Guelph Rivalry: Opposition from the White Guelphs, including Corso Donati

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, was deeply entangled in the political turmoil of late 13th- and early 14th-century Florence. His primary political enemies were the White Guelphs, a faction that opposed his own alignment with the Black Guelphs. The rivalry between these two factions was not merely ideological but also deeply personal, with figures like Corso Donati emerging as a central antagonist in Dante's political life. This opposition played a pivotal role in Dante's exile from Florence in 1302, shaping both his personal fate and his literary legacy.

The White Guelphs were a political faction in Florence that supported papal authority and sought to limit the influence of the Black Guelphs, who were more aligned with the Holy Roman Empire. Corso Donati, a charismatic and powerful leader of the White Guelphs, was a particularly fierce adversary of Dante. Donati's influence extended beyond politics; he was a military leader and a dominant figure in Florentine society, making him a formidable opponent. His rivalry with Dante was not just about political ideology but also about power and control over Florence. Donati's faction accused the Black Guelphs, including Dante, of corruption and misgovernance, escalating tensions between the two groups.

Dante's role as a prior (a member of Florence's governing council) in 1300 placed him at the heart of the city's political struggles. His alignment with the Black Guelphs and his efforts to maintain a balance of power between Florence and the papacy made him a target for the White Guelphs. Corso Donati, in particular, saw Dante as a threat to his own ambitions. The White Guelphs, under Donati's leadership, accused Dante and his allies of treason and mismanagement, culminating in a series of political trials and eventual exile for Dante and other Black Guelph leaders in 1302. This exile was a direct result of the White Guelphs' opposition, led by Donati, who sought to eliminate their rivals and consolidate power.

The personal animosity between Dante and Corso Donati is evident in Dante's writings. In *The Divine Comedy*, particularly in *Purgatorio*, Dante portrays Donati in a negative light, reflecting their real-life rivalry. Donati's death in 1308, before Dante's completion of the *Comedy*, did not diminish his significance as a symbol of opposition in Dante's eyes. The White Guelphs' victory over the Black Guelphs not only shaped Dante's life but also influenced his worldview, which is reflected in his portrayal of political and moral justice in his works.

The White Guelph Rivalry was more than a political conflict; it was a battle for the soul of Florence. Dante's opposition to the White Guelphs, and particularly to Corso Donati, was rooted in his belief in good governance and his resistance to what he saw as papal overreach. His exile, orchestrated by his political enemies, transformed him from a politician into a poet of universal significance. The legacy of this rivalry is immortalized in Dante's literature, where he explores themes of justice, betrayal, and the consequences of political ambition. Through his works, Dante not only condemned his enemies but also elevated his own vision of a just and harmonious society, forever linking his personal struggles with his artistic achievement.

Could the U.S. Government Function Without Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Exile by Black Guelphs: Banishment by the Black Guelphs for political allegiance

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, faced significant political turmoil during his lifetime, which ultimately led to his exile from Florence. His political enemy was the Black Guelph faction, a powerful political group that opposed his own alignment with the White Guelphs. The Guelphs and Ghibellines were two rival factions in medieval Italy, with the Guelphs supporting the Pope and the Ghibellines supporting the Holy Roman Emperor. Within the Guelph party, further divisions arose, leading to the formation of the Black and White Guelphs. Dante's allegiance to the White Guelphs, who advocated for greater civic autonomy and opposed papal interference in Florentine politics, placed him in direct conflict with the Black Guelphs, who were staunch supporters of the Pope and sought to consolidate papal influence in Florence.

The Black Guelphs, led by figures such as Corso Donati, gained dominance in Florence in the early 14th century. Dante, who had held political office in Florence as a member of the White Guelphs, became a target for his outspoken criticism of papal authority and his support for the city's independence. In 1302, after the Black Guelphs seized control of Florence with the backing of Pope Boniface VIII, Dante was accused of corruption and political conspiracy. Despite his absence from the city at the time, he was tried in absentia, found guilty, and sentenced to exile. The banishment was not merely a political punishment but also a personal and professional devastation for Dante, as it severed his ties to his homeland, his patrons, and his intellectual community.

The exile imposed by the Black Guelphs was particularly harsh, as it included severe penalties for anyone who aided Dante or attempted to facilitate his return. He was fined, stripped of his property, and condemned to be burned at the stake if he were ever to return to Florence. This extreme measure underscores the depth of the Black Guelphs' animosity toward Dante and their determination to eliminate him as a political threat. Dante's unwavering commitment to his principles and his refusal to align with the Black Guelphs or the Pope made him an irreconcilable enemy in their eyes.

Dante's exile profoundly influenced his literary work, particularly *The Divine Comedy*, where he often expressed his bitterness toward his political enemies and his longing for justice. In the *Inferno*, for example, he places several of his Florentine adversaries, including members of the Black Guelph faction, in the circles of Hell, symbolizing their moral and political corruption. His banishment also forced him to seek refuge in various Italian city-states, where he continued to write and engage in intellectual pursuits, though he never ceased to yearn for his return to Florence.

The conflict between Dante and the Black Guelphs exemplifies the intense political and ideological struggles of medieval Italy, where allegiances to the Pope or the Emperor could determine one's fate. Dante's exile by the Black Guelphs for his political allegiance to the White Guelphs remains a pivotal moment in his life, shaping both his personal trajectory and his literary legacy. It serves as a testament to the enduring consequences of political enmity and the resilience of those who remain true to their convictions in the face of adversity.

Oprah's Political Party: Unraveling Her Affiliation and Influence in Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Papal Opposition: Conflict with Pope Boniface VIII over Church-State relations

The conflict between Dante Alighieri and Pope Boniface VIII was deeply rooted in the broader struggle over Church-State relations during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Boniface VIII, who served as Pope from 1294 to 1303, was a staunch advocate for the absolute authority of the papacy over secular rulers. His most famous assertion of this power came in the form of the papal bull *Unam Sanctam* (1302), which declared that it was "absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff." This uncompromising stance directly challenged the authority of secular leaders, particularly in Italy, where city-states like Florence were fiercely protective of their independence.

Dante, a prominent Florentine politician and intellectual, found himself at odds with Boniface VIII due to his own political convictions and his city's resistance to papal interference. Florence, a stronghold of the Guelph faction (which supported the papacy), was internally divided between the White Guelphs, who favored papal influence, and the Black Guelphs, who opposed it. Dante aligned himself with the White Guelphs initially but later grew critical of both factions, especially after Boniface VIII's intervention in Florentine politics. The Pope's appointment of Charles of Valois to restore papal authority in Florence led to the expulsion of the White Guelphs in 1302, including Dante, who was condemned to exile and fined.

The personal and political consequences of Boniface VIII's actions fueled Dante's animosity toward the Pope. In his masterpiece, *The Divine Comedy*, Dante reserved a place for Boniface VIII in the eighth circle of Hell, among the fraudsters, specifically the sowers of discord. This literary condemnation reflects Dante's belief that Boniface had abused his spiritual authority for political gain, undermining the moral integrity of the Church. Dante's critique extended beyond Boniface as an individual to the broader issue of papal overreach, which he saw as a corruption of the Church's mission.

The conflict between Dante and Boniface VIII also highlights the intellectual and theological debates of the time. Dante, in works like *De Monarchia* (On World Government), argued for the separation of Church and State, advocating for a universal empire under the Holy Roman Emperor as the ideal secular authority. This vision directly contradicted Boniface VIII's claims of papal supremacy. For Dante, the Pope's role was spiritual, not temporal, and Boniface's attempts to dominate secular affairs were a perversion of divine order.

In summary, the opposition between Dante and Pope Boniface VIII was a pivotal aspect of the broader struggle over Church-State relations in medieval Italy. Boniface's assertion of absolute papal authority clashed with Dante's vision of a balanced, dual authority between the Church and the Empire. This conflict not only shaped Dante's political exile and literary work but also underscored the enduring tensions between spiritual and secular power in the medieval world. Dante's critique of Boniface VIII remains a powerful testament to his commitment to justice, independence, and the proper role of the Church in society.

Reagan's Political Affiliation: Unraveling the Party Behind the Iconic President

You may want to see also

Florence's Political Betrayal: Dante's lifelong enmity toward Florence's ruling elite

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, harbored a deep and lifelong enmity toward Florence’s ruling elite, a sentiment rooted in the political betrayals he experienced during his life. Dante was a staunch supporter of the White Guelphs, a political faction in Florence that opposed the papal influence and sought to maintain the city’s autonomy. The ruling elite, however, were aligned with the Black Guelphs, who were more sympathetic to the Pope and ultimately gained control of Florence through a series of political maneuvers and betrayals. This shift in power led to Dante’s exile in 1302, a punishment orchestrated by his political enemies that would shape his worldview and literary legacy.

The betrayal Dante felt was deeply personal and ideological. Florence, his beloved city, had been taken over by what he saw as corrupt and power-hungry elites who prioritized their own interests over the common good. The Black Guelphs, led by figures like Corso Donati, engineered Dante’s exile by accusing him of corruption and barring him from returning under threat of death. This act of political retribution was not merely a punishment for Dante’s political activities but also a symbolic silencing of his voice, which had become increasingly critical of the ruling class. Dante’s exile was a turning point in his life, transforming him from an active participant in Florentine politics into a bitter observer and critic of its rulers.

Dante’s enmity toward Florence’s elite is vividly expressed in his works, particularly in *The Divine Comedy*. In the *Inferno*, he reserves some of the most brutal punishments for those he considered traitors to Florence and its ideals. Figures like Bocca degli Abati, a fellow White Guelph who betrayed his cause, are depicted in the lowest circles of Hell, symbolizing Dante’s disdain for those who compromised their principles for political gain. Through his poetry, Dante not only condemned his enemies but also immortalized their betrayal, ensuring that their actions would be remembered with infamy.

The political betrayal Dante experienced was not just a personal tragedy but also a reflection of the broader turmoil in medieval Italy. Florence, a city-state known for its wealth and cultural achievements, was plagued by factionalism and power struggles. Dante’s exile highlighted the fragility of political alliances and the ruthless nature of the ruling elite, who were willing to sacrifice individuals like Dante to consolidate their power. His lifelong enmity was thus both a response to his own suffering and a critique of the systemic corruption that undermined Florence’s potential for greatness.

In conclusion, Dante’s enmity toward Florence’s ruling elite was a direct result of their political betrayal, which led to his exile and shaped his literary and philosophical outlook. His works serve as a testament to the enduring impact of this betrayal, not only on his life but also on his vision of justice and morality. Through his poetry, Dante ensured that the actions of his political enemies would be remembered, not just as historical events, but as moral failures that betrayed the ideals of Florence and its people. His lifelong enmity, therefore, is a powerful reminder of the consequences of political corruption and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of injustice.

Ancient Rome's Political Landscape: Factions, Alliances, and Power Struggles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Dante's primary political enemy was the Black Guelph faction, particularly those aligned with Pope Boniface VIII, who supported the papal interests over the independence of Florence.

Dante was a member of the White Guelphs, who opposed the Black Guelphs and advocated for Florentine autonomy. His political alignment with the Whites led to his exile when the Blacks gained power in 1302.

Charles of Valois, a French nobleman and ally of Pope Boniface VIII, played a significant role in Dante's exile by leading a military campaign that ousted the White Guelphs from Florence in 1301.