John C. Calhoun, a prominent American statesman and vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, had several political adversaries throughout his career, most notably Andrew Jackson. The intense rivalry between Calhoun and Jackson stemmed from their differing views on states' rights, tariffs, and the Nullification Crisis. Calhoun, a staunch advocate for states' rights and nullification, clashed with Jackson over the Tariff of 1828, which Calhoun deemed unconstitutional and harmful to the South. This disagreement escalated during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, where Calhoun secretly drafted the South Carolina Ordinance of Nullification, directly challenging Jackson's authority. Jackson, a strong unionist, responded forcefully, threatening to use military action to enforce federal law. Their ideological differences and personal animosity not only defined their relationship but also shaped the political landscape of the antebellum United States, highlighting the growing tensions between federal and state power.

Characteristics of John C. Calhoun's Political Enemy

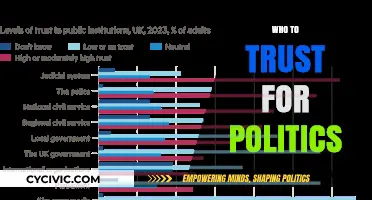

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Daniel Webster |

| Political Affiliation | Whig Party |

| Region | North (Massachusetts) |

| Views on Slavery | Opposed the expansion of slavery, believed in the Union's preservation |

| Views on States' Rights | Supported a strong federal government, opposed nullification |

| Key Debates | Engaged in famous debates with Calhoun, notably the Webster-Hayne debate of 1830 |

| Legacy | Remembered as a powerful orator and advocate for national unity |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

John C. Calhoun vs. Andrew Jackson

The intense political rivalry between John C. Calhoun and Andrew Jackson defined much of the early 19th-century American political landscape. Calhoun, a staunch advocate of states' rights and nullification, clashed ideologically with Jackson, a fervent nationalist and champion of federal authority. Their disagreements were rooted in fundamental differences over the role of the federal government, the balance of power between states and the Union, and the issue of tariffs, particularly the controversial Tariff of 1828, which Calhoun deemed oppressive to Southern economic interests. This tariff, often called the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners, became a rallying point for Calhoun's arguments in favor of states' rights and the doctrine of nullification, which asserted that states could invalidate federal laws they deemed unconstitutional.

Andrew Jackson, as President, vehemently opposed Calhoun's nullification doctrine, viewing it as a direct threat to the Union. Jackson believed in a strong federal government and considered secession or nullification as acts of treason. The conflict reached its peak during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, when South Carolina, under Calhoun's influence, declared the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void. Jackson responded forcefully, declaring in his Proclamation to the People of South Carolina that states did not have the right to nullify federal laws and threatening to use military force to enforce federal authority. This standoff ultimately led to a compromise, but it deepened the personal and political rift between the two men.

Their rivalry was also fueled by personal animosity and competing ambitions. Calhoun, who had served as Jackson's vice president from 1829 to 1832, resigned amid tensions over the Petticoat Affair, a social scandal involving their wives. However, the primary cause of their estrangement was Calhoun's secret involvement in the Censure of Jackson by the Senate in 1834. Calhoun, then a senator, had orchestrated the censure over Jackson's removal of federal deposits from the Second Bank of the United States, a move Calhoun saw as an abuse of presidential power. When Calhoun's role in the censure became public, Jackson was furious, further poisoning their relationship.

Ideologically, Calhoun's vision of a decentralized Union, where states held supreme authority, directly contradicted Jackson's belief in a strong, unified nation under federal leadership. Calhoun's defense of slavery and Southern economic interests also placed him at odds with Jackson's broader appeal to the common man, though Jackson himself was a slaveholder. Their conflicting views on the Indian Removal Act and the treatment of Native Americans highlighted another area of disagreement, with Calhoun supporting Jackson's policies but for different reasons, often tied to expanding Southern agricultural interests.

The legacy of their rivalry shaped American politics, particularly the growing divide between the North and South. Calhoun's ideas on states' rights and nullification became cornerstones of Southern secessionist thought, while Jackson's nationalism and assertion of federal power set a precedent for future presidents. Their clash foreshadowed the deeper sectional conflicts that would culminate in the Civil War. In essence, the John C. Calhoun vs. Andrew Jackson rivalry was not merely personal but a profound ideological struggle over the soul of the nation, with Calhoun emerging as Jackson's most formidable political enemy.

Switching Sides: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Your Political Party

You may want to see also

Calhoun's clash with Henry Clay

John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay, two towering figures in early 19th-century American politics, frequently clashed over fundamental issues like states' rights, tariffs, and the nature of the Union. Their rivalry was not merely personal but embodied the deep ideological divisions between the South and the West, regions they respectively championed. Calhoun, a staunch advocate for states' rights and Southern agrarian interests, viewed Clay, the "Great Compromiser" and champion of national economic development, as a dangerous proponent of federal overreach. Clay, in turn, saw Calhoun's states' rights doctrine as a threat to the Union's integrity and his American System—a program promoting tariffs, internal improvements, and a national bank—as essential for national prosperity.

One of their most significant clashes occurred during the debates over the Tariff of 1828, known as the "Tariff of Abominations" in the South. Calhoun, though he publicly supported the tariff to maintain political unity, privately opposed it, understanding its devastating impact on the South's economy. Clay, a key architect of the tariff, argued it would protect Northern and Western industries and fund internal improvements. When South Carolina later declared the tariff null and void in 1832, Calhoun anonymously authored the *South Carolina Exposition and Protest*, articulating the doctrine of nullification—the idea that states could invalidate federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. Clay vehemently opposed nullification, seeing it as a direct assault on federal authority and the Union.

The Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833 brought their conflict to a head. Calhoun resigned as Vice President under Andrew Jackson to take a Senate seat, where he could more effectively defend South Carolina's position. Clay, seeking to defuse the crisis, crafted the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which gradually reduced tariff rates over a decade. While this temporarily resolved the issue, it did little to bridge the ideological gap between Calhoun and Clay. Calhoun viewed the compromise as a temporary concession, while Clay saw it as a victory for the Union and his gradualist approach to policy.

Their rivalry extended beyond tariffs to broader debates about the Union's future. Calhoun's growing embrace of secessionist ideas, particularly in his later years, directly contradicted Clay's unwavering commitment to national unity. Clay's famous slogan, "the Union must be preserved," stood in stark opposition to Calhoun's belief that states had the right to secede if their interests were threatened. This fundamental disagreement made reconciliation impossible, as their visions for America were increasingly irreconcilable.

In the Senate, their oratory duels were legendary, with Calhoun's intellectual rigor and Clay's persuasive eloquence captivating their colleagues. Despite their mutual respect as political adversaries, their clashes were sharp and consequential. Their disagreements over tariffs, nullification, and states' rights not only defined their careers but also foreshadowed the sectional tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War. Calhoun and Clay's rivalry remains a pivotal chapter in American political history, illustrating the profound ideological divides that shaped the nation's trajectory.

Nixon's Resignation: Did It Cripple His Party's Political Future?

You may want to see also

Daniel Webster as Calhoun's opponent

John C. Calhoun, a prominent American politician and intellectual force of the antebellum South, had several political adversaries throughout his career, but one of his most notable opponents was Daniel Webster. A towering figure in American politics during the first half of the 19th century, Webster was a Whig senator from Massachusetts and a staunch advocate for national unity and economic modernization. His clashes with Calhoun were emblematic of the deep ideological divisions between the North and South, particularly on issues such as tariffs, states' rights, and the expansion of slavery.

The rivalry between Calhoun and Webster was most vividly displayed during the debates over the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833. Calhoun, then Vice President under Andrew Jackson, championed the doctrine of nullification, which asserted that states had the right to invalidate federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. This doctrine was a direct response to the Tariff of 1828, which Calhoun and other Southerners labeled the "Tariff of Abominations" because it heavily taxed imported goods, disproportionately harming the agrarian South. Webster, in contrast, vehemently opposed nullification, arguing that it threatened the integrity of the Union and the supremacy of federal law. His famous reply to Senator Robert Hayne in the Senate, known as the "Second Reply to Hayne," articulated a powerful defense of national sovereignty and the Constitution, directly countering Calhoun's states' rights arguments.

Another major point of contention between Webster and Calhoun was the issue of slavery and its role in the American political system. Calhoun was an unapologetic defender of slavery, viewing it as a "positive good" and essential to the Southern way of life. He also argued that the South must protect its economic and political interests against perceived Northern aggression. Webster, while not an abolitionist, took a more moderate stance, focusing on preserving the Union rather than challenging the institution of slavery directly. His commitment to national unity often placed him in opposition to Calhoun's increasingly sectional and pro-slavery agenda.

The two men also clashed over economic policies, particularly tariffs and internal improvements. Webster supported protective tariffs and federal funding for infrastructure projects, such as roads and canals, as part of his vision for a strong, industrialized nation. Calhoun, on the other hand, opposed these measures, arguing that they benefited the North at the expense of the South. Their disagreements on these issues highlighted the broader economic and cultural divide between the industrial North and the agrarian South, with Webster and Calhoun becoming symbols of their respective regions' interests.

In the Senate, Webster and Calhoun were known for their oratorical brilliance, and their debates were among the most memorable in American legislative history. Webster's eloquence and appeal to national unity often contrasted sharply with Calhoun's intellectual rigor and emphasis on states' rights and Southern grievances. Their rivalry was not merely personal but represented the clash of two competing visions for the future of the United States. While Calhoun sought to protect Southern interests and maintain the balance of power between states and the federal government, Webster championed a stronger central government and a unified nation.

In conclusion, Daniel Webster stood as one of John C. Calhoun's most formidable political opponents, embodying the Northern perspective in contrast to Calhoun's Southern ideology. Their disagreements over nullification, slavery, tariffs, and the role of the federal government defined many of the key political debates of their era. Webster's unwavering commitment to the Union and his ability to articulate a compelling case for national unity made him a natural adversary to Calhoun's sectional and states' rights arguments. Their rivalry remains a critical chapter in understanding the political and ideological conflicts that ultimately led to the Civil War.

Political Parties: Essential Pillars or Hindrances to American Democracy?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Conflict with John Quincy Adams

John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams were two prominent figures in early 19th-century American politics, and their ideological differences often led to intense political conflicts. Calhoun, a staunch advocate for states' rights and Southern interests, frequently clashed with Adams, who held more nationalist and abolitionist views. Their rivalry was not merely personal but deeply rooted in their contrasting visions for the future of the United States. One of the earliest points of contention between Calhoun and Adams was during the 1824 presidential election, known as the "Corrupt Bargain." Calhoun, initially a supporter of William H. Crawford, later aligned with Adams after Adams won the presidency. However, Calhoun's relationship with Adams soured quickly due to their differing policies and priorities.

A significant source of conflict between Calhoun and Adams was their opposing stances on tariffs. Calhoun, as a representative of the agrarian South, vehemently opposed the Tariff of 1828, which he dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations." He argued that it unfairly benefited Northern industrialists at the expense of Southern farmers. Adams, on the other hand, supported protective tariffs as a means to foster American industry and economic independence. This disagreement escalated tensions between the two, with Calhoun becoming a vocal critic of Adams's economic policies. Calhoun's growing frustration with Adams's administration led him to champion the doctrine of nullification, which asserted that states had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional.

Another major point of conflict was their differing views on slavery and the role of the federal government. Adams, though not an outright abolitionist, was sympathetic to anti-slavery sentiments and opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. Calhoun, in contrast, was a fierce defender of slavery and Southern rights, viewing any federal interference in the institution as a threat to Southern autonomy. This ideological divide was further exacerbated by Adams's support for internal improvements and federal infrastructure projects, which Calhoun saw as an overreach of federal power and a threat to states' rights.

The conflict between Calhoun and Adams reached a climax during Adams's presidency, particularly in the aftermath of the 1828 election. Calhoun, who had become Vice President under Adams, increasingly aligned himself with Andrew Jackson, Adams's political rival. Calhoun's shift in allegiance was driven by his disillusionment with Adams's policies and his belief that Jackson better represented Southern interests. This political maneuvering further strained his relationship with Adams, who viewed Calhoun's actions as a betrayal. By the end of Adams's presidency, the rift between the two men was irreparable, and their conflict had become a defining feature of the era's political landscape.

In summary, the conflict between John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams was rooted in their divergent ideologies and policy priorities. Their disagreements over tariffs, states' rights, slavery, and the role of the federal government created a deep and lasting political rivalry. This conflict not only shaped their personal relationship but also influenced the broader political dynamics of the time, contributing to the growing sectional tensions between the North and the South. Calhoun's eventual alignment with Andrew Jackson marked the end of his association with Adams and solidified his position as one of Adams's most formidable political enemies.

Shutdown Fallout: Which Political Parties Bear the Brunt?

You may want to see also

Calhoun vs. Abraham Lincoln's policies

John C. Calhoun and Abraham Lincoln were two of the most influential political figures in American history, representing starkly opposing views on critical issues such as states' rights, slavery, and the role of the federal government. Calhoun, a South Carolina senator and vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, was a staunch advocate for states' rights and nullification, believing that states had the authority to invalidate federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. His political philosophy was deeply rooted in the protection of Southern interests, particularly the institution of slavery, which he saw as essential to the Southern economy and way of life.

In contrast, Abraham Lincoln, who rose to prominence in the mid-19th century and became the 16th president of the United States, held fundamentally different views. Lincoln was a vocal opponent of slavery, arguing that it was morally wrong and incompatible with the nation's founding principles of liberty and equality. His policies were centered on preserving the Union and preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories. Lincoln believed in a stronger federal government that could ensure national unity and protect individual rights, a stance that directly clashed with Calhoun's emphasis on state sovereignty.

One of the most significant policy differences between Calhoun and Lincoln was their approach to slavery. Calhoun defended slavery as a "positive good" and sought to protect it through measures like the Fugitive Slave Act and the expansion of slavery into new states. He argued that the South's economic survival depended on slave labor and that any federal interference with slavery was an infringement on states' rights. Lincoln, on the other hand, pushed for the gradual abolition of slavery, most notably through the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared freedom for slaves in Confederate-held territories during the Civil War. His ultimate goal was to eradicate slavery entirely, as evidenced by his support for the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Another critical area of divergence was their views on the role of the federal government. Calhoun championed the doctrine of nullification, famously articulated in his *South Carolina Exposition and Protest* (1828), which asserted that states could nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. This idea was a direct challenge to federal authority and was exemplified in the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833. Lincoln vehemently opposed such notions, arguing that the Union was perpetual and indivisible, and that the federal government had the supreme authority to enforce its laws. His inaugural address in 1861 emphasized the need to preserve the Union, even as Southern states seceded in response to his election.

Economically, Calhoun and Lincoln also had differing priorities. Calhoun supported policies that benefited the agrarian South, including low tariffs and the protection of slave-based agriculture. He opposed high tariffs, such as the "Tariff of Abominations" in 1828, which he believed unfairly benefited the industrial North at the expense of the South. Lincoln, however, favored higher tariffs to protect American industries and fund internal improvements like railroads and infrastructure, which he saw as essential for national economic growth. His economic policies were more aligned with the interests of the North and the emerging industrial economy.

In summary, the policies of John C. Calhoun and Abraham Lincoln were diametrically opposed, reflecting the deep regional and ideological divides of their time. Calhoun's defense of states' rights, nullification, and slavery stood in stark contrast to Lincoln's commitment to national unity, federal authority, and the abolition of slavery. Their conflicting visions for America ultimately contributed to the tensions that led to the Civil War, making their ideological battle one of the most defining struggles in American political history.

Is Power Equally Distributed Among Political Parties? A Critical Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

John C. Calhoun's primary political enemy was Daniel Webster, a prominent Whig leader and senator from Massachusetts. Their rivalry was particularly intense during debates over states' rights, tariffs, and the Nullification Crisis.

Yes, Calhoun had a significant political enemy within his own Democratic Party in the form of President Andrew Jackson. Their disagreements over nullification, tariffs, and federal authority led to a bitter personal and political rift.

Yes, Henry Clay, a Whig leader and senator from Kentucky, was another of Calhoun's political enemies. Clay and Calhoun clashed over issues like the Tariff of Abominations, internal improvements, and the balance between federal and state powers.

While Calhoun's primary enemies were political figures like Webster, Clay, and Jackson, he also fiercely opposed abolitionists, particularly those in the North, who challenged his defense of slavery and states' rights. Figures like William Lloyd Garrison were ideological adversaries.