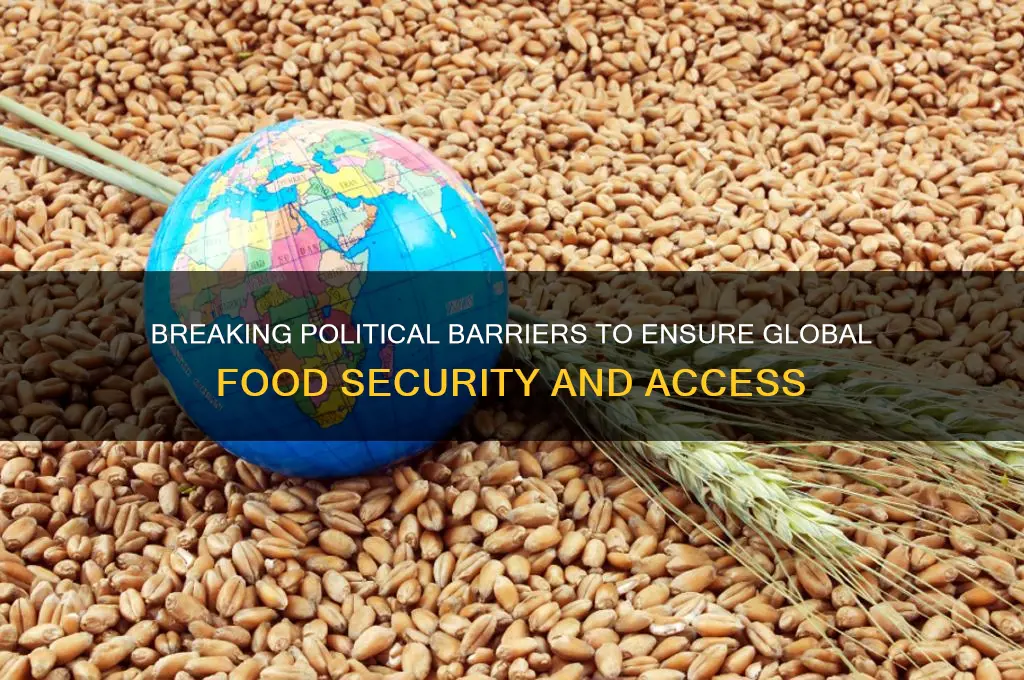

Political barriers to food access and security are complex and multifaceted, stemming from policies, governance structures, and power dynamics that often prioritize economic or political interests over the basic needs of populations. These barriers manifest in various forms, including trade restrictions, subsidies that distort markets, land tenure policies favoring elites, and inadequate investment in agricultural infrastructure. Additionally, geopolitical conflicts, corruption, and the marginalization of smallholder farmers and vulnerable communities exacerbate food insecurity. Addressing these challenges requires not only policy reforms but also international cooperation, equitable resource distribution, and a commitment to prioritizing human rights and sustainability over short-term political gains.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Policy Inconsistencies | Conflicting policies across sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, trade) hinder coordinated efforts to ensure food security. |

| Lack of Political Will | Insufficient commitment from governments to prioritize food security and nutrition, often due to competing priorities. |

| Corruption | Mismanagement of resources, embezzlement, and bribery divert funds meant for food programs. |

| Trade Barriers | Tariffs, subsidies, and export restrictions distort global food markets, limiting access to affordable food. |

| Land Tenure Issues | Insecure land rights, especially for smallholder farmers, reduce investment in sustainable agriculture. |

| Climate Policy Gaps | Inadequate policies to address climate change impacts on food production and distribution. |

| Food Safety Regulations | Overly stringent or poorly enforced regulations can limit food availability, especially in low-income countries. |

| Subsidy Misalignment | Subsidies often favor large-scale, monoculture farming over diverse, sustainable practices. |

| Political Instability | Conflict and governance failures disrupt food production, distribution, and access. |

| Global Governance Weaknesses | Ineffective international cooperation and enforcement of agreements related to food security. |

| Urbanization Policies | Rapid urbanization without adequate planning can lead to food deserts and reduced access to nutritious food. |

| Gender Inequality in Policy | Policies often overlook the role of women in agriculture, limiting their access to resources and decision-making. |

| Corporate Influence | Lobbying by agribusinesses can shape policies in favor of profit over public health and sustainability. |

| Data and Monitoring Gaps | Lack of robust data and monitoring systems hinders evidence-based policymaking for food security. |

| Emergency Response Delays | Slow political response to food crises exacerbates hunger and malnutrition. |

| Cultural and Social Barriers | Political neglect of cultural food practices and social norms that affect dietary choices. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Government policies restricting food imports/exports

Government policies restricting food imports and exports are significant political barriers that impact global food security, trade dynamics, and economic stability. These policies are often implemented to protect domestic agricultural sectors, ensure food self-sufficiency, or address trade imbalances. However, they can also lead to higher food prices, reduced availability of certain products, and strained international relations. One common approach is the imposition of tariffs, which are taxes on imported goods. High tariffs on food products make them more expensive for consumers and less competitive compared to domestically produced alternatives. For instance, many countries apply tariffs on dairy products, grains, and meats to shield local farmers from foreign competition, but this can limit consumer choice and increase costs for food-importing nations.

Another restrictive measure is the use of quotas, which limit the quantity of specific food products that can be imported or exported. Export quotas are often used to ensure domestic food supplies remain stable, especially during times of scarcity. For example, during periods of drought or crop failure, governments may restrict the export of staple foods like rice or wheat to prioritize local consumption. Conversely, import quotas are used to control the influx of foreign goods, protecting domestic producers but potentially reducing the diversity of food available in the market. These quotas can create artificial shortages or surpluses, distorting global food markets and affecting vulnerable populations.

Non-tariff barriers, such as stringent sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, are also employed to restrict food trade. Governments often justify these measures as necessary to protect public health and prevent the spread of pests and diseases. However, they can be used as trade barriers when applied excessively or arbitrarily. For example, a country might impose strict regulations on the import of fruits and vegetables, citing concerns about pesticide residues, even if the products meet international safety standards. Such practices can effectively block imports, favoring domestic producers while limiting consumer access to affordable or specialized food items.

Subsidies and financial incentives for domestic agriculture are another form of policy restriction, albeit indirect. By providing financial support to local farmers, governments can make domestically produced food cheaper than imported alternatives, effectively discouraging imports. While subsidies can bolster food security and rural livelihoods, they can also lead to overproduction and distort global markets. For instance, heavily subsidized crops like corn or sugar in certain countries can be exported at prices below production costs, undercutting farmers in developing nations and creating long-term dependency on subsidized imports.

Finally, embargoes and trade bans represent the most extreme form of food import/export restrictions. These measures are typically imposed for political or strategic reasons, such as economic sanctions or geopolitical conflicts. For example, a country might ban food exports to a neighboring nation as a form of political pressure, or it might prohibit imports from a specific country in response to a trade dispute. Such actions can have severe consequences, particularly for food-insecure regions that rely on international trade to meet their nutritional needs. Embargoes often exacerbate hunger and malnutrition, highlighting the humanitarian impact of politicizing food trade.

In conclusion, government policies restricting food imports and exports are multifaceted tools with far-reaching implications. While they serve legitimate purposes such as protecting domestic industries and ensuring food security, they can also create inefficiencies, increase costs, and exacerbate inequalities in the global food system. Striking a balance between national interests and international cooperation is essential to address these political barriers and promote a more equitable and sustainable food trade environment.

Does AARP Support Political Parties? Uncovering Donation Allegations and Facts

You may want to see also

Trade agreements limiting agricultural access

Trade agreements, while designed to facilitate international commerce, often include provisions that inadvertently limit agricultural access, creating political barriers to food security. One of the primary mechanisms through which this occurs is the imposition of tariffs and quotas on agricultural products. High tariffs make imported food products more expensive, reducing their accessibility for both consumers and local industries that rely on these inputs. For instance, developing countries often face steep tariffs when exporting agricultural goods to wealthier nations, stifling their ability to compete in global markets. This not only limits their economic growth but also reduces the diversity and availability of food products globally.

Another significant issue arises from the inclusion of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures in trade agreements. While these measures are intended to protect human, animal, and plant health, they are sometimes used as non-tariff barriers to restrict agricultural imports. Wealthier nations may impose stringent standards that are difficult for smaller or less developed countries to meet, effectively blocking their access to lucrative markets. This creates an uneven playing field, where only large-scale, well-resourced producers can comply with the regulations, marginalizing smallholder farmers and limiting the overall availability of food products.

Bilateral and regional trade agreements can also exacerbate food access issues by prioritizing the interests of signatory countries over those of non-participants. For example, preferential trade agreements may grant exclusive access to certain markets, leaving out other nations that rely on those markets for food imports. This exclusivity can lead to higher prices and reduced availability of essential food commodities in non-signatory countries, particularly in regions already vulnerable to food insecurity. Such agreements often lack mechanisms to ensure that food access is equitably distributed, further entrenching political barriers to food.

Furthermore, intellectual property rights (IPR) provisions in trade agreements, such as those related to plant varieties and seeds, can limit agricultural access by restricting farmers' ability to save, exchange, and replant seeds. These provisions often favor multinational corporations over small-scale farmers, who may be unable to afford patented seeds or face legal repercussions for traditional farming practices. This not only undermines agricultural biodiversity but also increases the cost of production, making food less accessible for both farmers and consumers. The concentration of seed ownership in the hands of a few corporations reduces the resilience of food systems, making them more susceptible to shocks and disruptions.

Lastly, the lack of transparency and inclusivity in negotiating trade agreements often results in policies that favor powerful stakeholders at the expense of vulnerable populations. Smallholder farmers, indigenous communities, and low-income countries are rarely represented in these negotiations, leading to agreements that fail to address their specific needs. For instance, trade liberalization policies may open up markets to cheap, subsidized agricultural products from wealthier nations, undercutting local producers and destabilizing domestic food systems. Without safeguards to protect small-scale agriculture and ensure food sovereignty, trade agreements can become tools of exclusion rather than instruments of equitable development.

In conclusion, trade agreements, while intended to promote economic growth, often create political barriers to food access through tariffs, SPS measures, preferential market access, IPR restrictions, and exclusionary negotiation processes. Addressing these issues requires a reevaluation of trade policies to prioritize food security, equity, and sustainability. This includes fostering inclusive negotiations, implementing safeguards for vulnerable populations, and ensuring that trade agreements do not undermine the ability of countries to feed their populations. By doing so, the global community can work toward dismantling the political barriers that limit agricultural access and hinder progress toward food security for all.

Does the ABA Show Political Bias? Uncovering Party Affiliations

You may want to see also

Subsidies distorting global food markets

Agricultural subsidies, primarily provided by developed nations, are a significant political barrier to fair and equitable global food markets. These subsidies, often aimed at supporting domestic farmers, have far-reaching consequences that distort international trade and undermine food security in many developing countries. The issue lies in the fact that these financial incentives allow subsidized farmers to produce and export goods at artificially low prices, making it nearly impossible for farmers in other parts of the world to compete. This practice not only disrupts local agricultural sectors but also contributes to a global food system that favors a few dominant players.

The impact of these subsidies is particularly detrimental to small-scale farmers in low-income countries. When subsidized agricultural products flood the global market, local producers struggle to sell their goods at competitive prices. As a result, many farmers in developing nations are forced to abandon their crops or sell at a loss, leading to decreased income and, in some cases, poverty. This situation creates a cycle of dependency, where these countries become reliant on imported food, often from the very nations providing the subsidies, further exacerbating the imbalance in the global food trade.

One of the most well-known examples of this distortion is the cotton industry. Heavily subsidized cotton farmers in the United States, for instance, can produce and export cotton at prices that undercut those of farmers in West Africa. This has led to significant economic losses for African cotton producers, who are unable to compete with the subsidized prices. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has addressed this issue, ruling that such subsidies are illegal, but the practice persists, highlighting the political challenges in reforming these policies.

Furthermore, subsidies often encourage overproduction, leading to surplus goods that are then dumped onto the global market at reduced prices. This practice not only distorts market prices but also discourages sustainable farming practices. Farmers, driven by the need to maximize production to access subsidies, may resort to intensive farming methods that deplete natural resources and harm the environment. The long-term consequences include soil degradation, water scarcity, and reduced biodiversity, all of which threaten the very foundation of global food production.

Addressing these distortions requires international cooperation and a reevaluation of agricultural policies. Developed nations must reconsider their subsidy programs, ensuring they do not unfairly advantage their farmers at the expense of global food security. This could involve redirecting subsidies towards sustainable farming practices, research, and infrastructure development, which would benefit both domestic and international agricultural sectors. By removing these political barriers, the global food market can become more equitable, allowing farmers worldwide to compete fairly and contribute to a more stable and sustainable food system.

Refusing Service Based on Political Party: Legal or Discrimination?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$44.79 $55.99

$101.29 $158

Regulatory barriers to food distribution

Another critical regulatory barrier is the imposition of tariffs and trade restrictions on food imports and exports. While such measures are often justified as protecting domestic industries, they can lead to higher food prices and reduced availability, particularly in countries heavily reliant on food imports. For example, tariffs on staple foods like grains or dairy products can make these essential items unaffordable for vulnerable populations. Governments should consider revising trade policies to prioritize food security, potentially through targeted subsidies or preferential trade agreements that ensure a stable supply of affordable food.

Food safety regulations, though essential for public health, can also inadvertently create barriers to distribution. In some cases, overly stringent or inconsistently applied standards can exclude small-scale farmers and producers from formal markets. For instance, requirements for expensive certification or testing equipment may be unattainable for smallholders, forcing them into informal markets where food safety is less regulated. Policymakers should focus on developing context-specific regulations that balance safety with accessibility, such as providing training and affordable certification options for small producers.

Cross-border food distribution is particularly affected by regulatory barriers, including differing standards and customs procedures between countries. These discrepancies can lead to delays, spoilage, and increased costs, ultimately reducing the availability of food in import-dependent regions. Harmonizing food safety standards and simplifying customs processes through regional or international agreements could significantly improve the efficiency of cross-border food distribution. Initiatives like the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement) provide a framework for such harmonization, but greater political will and implementation are needed.

Lastly, regulatory barriers often fail to account for the unique challenges of distributing food in emergency situations, such as natural disasters or conflicts. Bureaucratic red tape, including lengthy approval processes for humanitarian aid, can delay the delivery of critical food supplies to affected populations. Governments and international organizations should establish emergency protocols that expedite the approval and distribution of food aid, ensuring that regulatory frameworks do not become obstacles to saving lives. By addressing these regulatory barriers, policymakers can create a more resilient and equitable food distribution system that meets the needs of all populations, especially the most vulnerable.

Disney's Political Influence: Uncovering the Magic Kingdom's Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Political instability disrupting food supply chains

Political instability poses a significant threat to food supply chains by creating unpredictable environments that hinder the production, distribution, and accessibility of food. In regions plagued by conflict, governments often struggle to maintain basic infrastructure, such as roads, storage facilities, and transportation networks, which are critical for moving food from farms to markets. Armed conflicts frequently lead to the destruction of agricultural lands, displacement of farmers, and disruption of markets, exacerbating food shortages. For instance, in war-torn countries like Syria and Yemen, prolonged instability has devastated local agriculture, forcing populations to rely heavily on humanitarian aid that is often delayed or insufficient due to logistical challenges and security risks.

Moreover, political instability often results in policy inconsistencies and weak governance, which further destabilize food systems. Governments in unstable regions may prioritize military spending over agricultural investment, neglecting essential support for farmers such as subsidies, access to credit, and extension services. Corruption and mismanagement of resources can also divert funds away from food security initiatives, leaving vulnerable populations without adequate support. In countries like South Sudan, political turmoil has led to the collapse of public institutions, making it nearly impossible to implement effective food security policies or coordinate humanitarian responses.

Trade disruptions are another critical consequence of political instability, as conflicts often lead to border closures, embargoes, and sanctions that restrict the flow of food and agricultural inputs. For example, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, both major global exporters of wheat and fertilizers, has caused significant spikes in food prices and shortages in importing countries, particularly in Africa and the Middle East. Such disruptions not only affect immediate food availability but also undermine long-term agricultural productivity by limiting access to essential inputs like seeds and fertilizers.

Political instability also fosters an environment of fear and uncertainty, deterring private sector investment in agriculture and food systems. Farmers and agribusinesses are less likely to invest in improving productivity or expanding operations when their assets and livelihoods are at risk of destruction or confiscation. This lack of investment perpetuates low agricultural yields and weak supply chains, making it difficult for countries to achieve food self-sufficiency or resilience in the face of crises. In Afghanistan, for instance, political upheaval has discouraged both domestic and international investment in agriculture, leaving the country highly dependent on food imports and vulnerable to global market fluctuations.

Finally, political instability often exacerbates existing inequalities, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities that are already food insecure. Women, children, and rural populations are particularly vulnerable, as they often lack the resources or mobility to adapt to sudden disruptions in food supply. Humanitarian organizations face immense challenges in reaching these populations due to insecurity and bureaucratic hurdles, further deepening the food crisis. Addressing the impact of political instability on food supply chains requires not only immediate humanitarian interventions but also long-term strategies to strengthen governance, promote peacebuilding, and invest in resilient agricultural systems.

Do Political Parties Always Exist? Exploring Their Historical Presence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political barriers to food access refer to policies, regulations, or government actions that limit the availability, affordability, or distribution of food, often disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations.

Trade policies, such as tariffs, subsidies, or export bans, can restrict the flow of food between countries, leading to shortages or price increases in importing nations, particularly in low-income regions.

Corruption can divert resources meant for food programs, distort markets, or enable unfair distribution systems, exacerbating food insecurity and inequality.

Political conflicts, such as wars or civil unrest, disrupt food production, supply chains, and humanitarian aid efforts, leading to famine and malnutrition in affected areas.

Yes, governments can implement policies like food subsidies, social safety nets, fair trade agreements, and anti-corruption measures to mitigate political barriers and improve food security.

![Geography in the 21st Century: Defining Moments that Shaped Society [2 volumes]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81mScas3VlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)