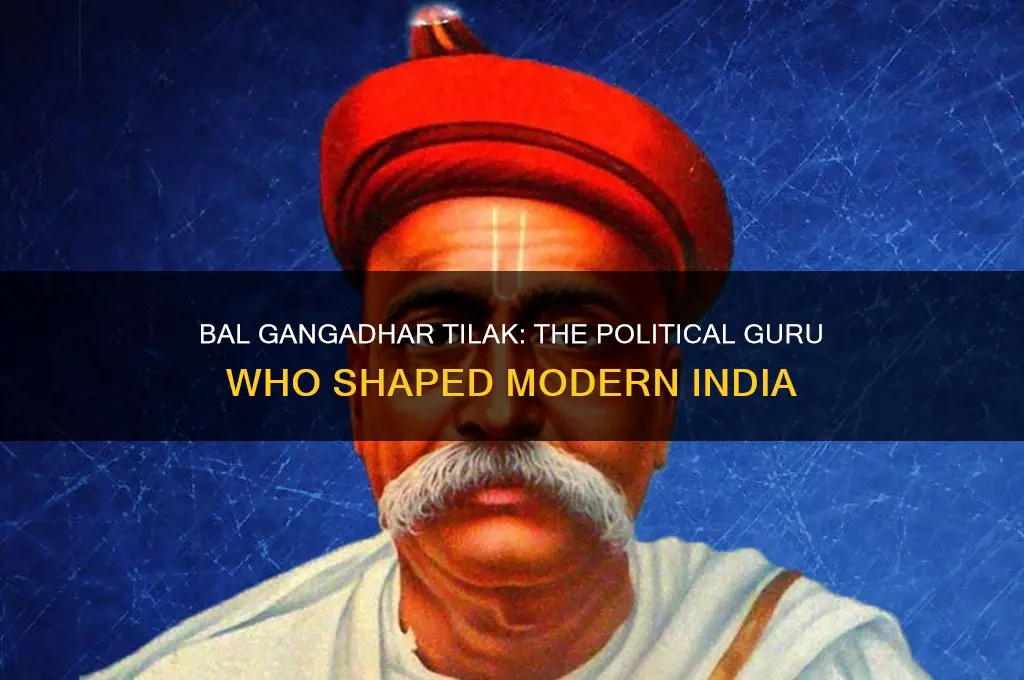

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a pivotal figure in India's independence movement, is often regarded as the political guru of several prominent leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi. Tilak's philosophy of 'Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it' became a rallying cry for the freedom struggle, inspiring generations to challenge British colonial rule. His emphasis on self-rule, cultural nationalism, and mass mobilization laid the ideological foundation for India's quest for independence. Leaders like Gandhi, though differing in methods, were deeply influenced by Tilak's unwavering commitment to national sovereignty and his ability to connect with the common people. Thus, Tilak's legacy as a political mentor continues to resonate in India's historical and political discourse.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lokmanya Tilak's Early Influences: Key figures and ideologies shaping Tilak's political thought and activism

- Mahadev Govind Ranade's Role: How Ranade mentored Tilak in social reform and political ideology

- Swami Vivekananda's Impact: Vivekananda's influence on Tilak's nationalism and spiritual-political vision

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak's Self-Education: His independent study of politics, philosophy, and revolutionary ideas

- Intellectual Peers and Debates: Tilak's interactions with contemporaries that refined his political philosophy

Lokmanya Tilak's Early Influences: Key figures and ideologies shaping Tilak's political thought and activism

Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a seminal figure in India's independence movement, was profoundly influenced by a constellation of key figures and ideologies during his formative years. Among the earliest and most significant influences was Maharashtra’s rich cultural and intellectual heritage. Tilak was deeply rooted in Marathi literature and the teachings of the Bhakti saints, particularly Sant Tukaram and Sant Eknath, whose emphasis on social equality and devotion to a singular truth resonated with him. These saints’ critiques of caste hierarchy and religious dogmatism laid the groundwork for Tilak’s later emphasis on social reform and national unity. Their teachings instilled in him a sense of pride in India’s indigenous culture, which became a cornerstone of his political ideology.

Another pivotal influence was Swami Vivekananda, whose speeches at the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago left an indelible mark on Tilak’s worldview. Vivekananda’s articulation of India’s spiritual and philosophical greatness on a global stage inspired Tilak to integrate Hindu spirituality with modern political thought. Tilak admired Vivekananda’s call for a resurgent India, free from colonial subjugation and rooted in its own cultural ethos. This encounter reinforced Tilak’s belief in the need for a national awakening that combined spiritual strength with political action, shaping his later advocacy for Swaraj (self-rule) as a divine and moral imperative.

Tilak’s intellectual development was also deeply shaped by his engagement with Western political thought, particularly the works of Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill. Spencer’s theories on social evolution and individual liberty influenced Tilak’s understanding of societal progress, while Mill’s emphasis on freedom and self-governance resonated with his growing nationalist sentiments. However, Tilak was careful to synthesize these Western ideas with India’s indigenous traditions, ensuring that his political thought remained firmly grounded in the Indian context. This blend of Eastern spirituality and Western political philosophy became a hallmark of his ideology.

A critical figure in Tilak’s early political awakening was Mahadev Govind Ranade, a social reformer and scholar. Although Tilak later diverged from Ranade’s moderate approach, Ranade’s emphasis on education, social reform, and legal advocacy left a lasting impression. Tilak’s initial involvement in the Deccan Education Society, co-founded by Ranade, exposed him to the importance of education as a tool for social and political transformation. This experience reinforced his belief in the need to empower the masses through knowledge, a principle that guided his later efforts to mobilize public opinion against British rule.

Finally, Tilak’s political thought was profoundly shaped by the Indian National Congress and its early leaders, such as Dadabhai Naoroji and Surendranath Banerjee. Naoroji’s economic critique of British colonialism, encapsulated in his "Drain Theory," provided Tilak with a framework for understanding the economic exploitation of India. Banerjee’s emphasis on constitutional agitation and public mobilization inspired Tilak’s early political activism. However, Tilak soon grew disillusioned with the Congress’s moderate approach, leading him to advocate for more radical methods of resistance. This shift marked the evolution of his political ideology, which increasingly emphasized mass mobilization, cultural revival, and direct confrontation with colonial authority.

In essence, Lokmanya Tilak’s early influences were a synthesis of Maharashtra’s cultural heritage, Hindu spiritual thought, Western political philosophy, and the nascent Indian nationalist movement. These diverse streams converged to shape his unique political ideology, which emphasized Swaraj, cultural pride, and the empowerment of the masses. Figures like Swami Vivekananda, Mahadev Govind Ranade, and the Bhakti saints, along with Western thinkers and early Congress leaders, collectively served as his political gurus, guiding his transformation into one of India’s most formidable freedom fighters.

Exploring Canada's Political Landscape: Do Political Parties Exist There?

You may want to see also

Mahadev Govind Ranade's Role: How Ranade mentored Tilak in social reform and political ideology

Mahadev Govind Ranade, a prominent social reformer and intellectual of the 19th century, played a pivotal role in shaping Bal Gangadhar Tilak's early thoughts on social reform and political ideology. Ranade, often regarded as Tilak's political guru, was a founding member of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, an organization that advocated for social and political change in India. Tilak, who joined the Sabha in 1870, was deeply influenced by Ranade's progressive ideas and his commitment to uplifting Indian society through education, legal reforms, and economic empowerment. Ranade's emphasis on rationalism, social equality, and the need for Indians to take charge of their own destiny left an indelible mark on Tilak's intellectual development.

Ranade's mentorship of Tilak was characterized by his focus on social reform as the foundation for political awakening. He believed that India's struggle for independence could only succeed if it was accompanied by internal social transformation. Ranade advocated for the eradication of social evils such as caste discrimination, child marriage, and the subjugation of women. He encouraged Tilak to engage with these issues, emphasizing that true nationalism required addressing the societal ills that held India back. Tilak, inspired by Ranade's vision, later integrated these social reform ideals into his own political philosophy, though he would eventually diverge from Ranade's moderate approach in favor of more radical methods.

In the realm of political ideology, Ranade instilled in Tilak the importance of constitutional agitation and the use of legal and intellectual tools to challenge British colonial rule. Ranade was a firm believer in working within the existing system to bring about change, advocating for Indian representation in legislative bodies and the promotion of indigenous industries. He encouraged Tilak to study Western political thought while remaining rooted in Indian traditions and values. This dual emphasis on modernity and cultural heritage became a hallmark of Tilak's political ideology, as he sought to blend Western democratic ideals with India's spiritual and historical legacy.

Ranade's influence on Tilak is also evident in their shared commitment to education as a tool for empowerment. Ranade was a key figure in the establishment of the Deccan Education Society, which aimed to provide modern education to Indians while preserving their cultural identity. Tilak, who later became a member of the Society, carried forward this mission by founding the Fergusson College and promoting vernacular education. Both Ranade and Tilak believed that an educated populace was essential for India's social and political liberation, and their efforts in this area laid the groundwork for future generations of Indian leaders.

Despite their eventual ideological differences, with Ranade adopting a moderate stance and Tilak embracing extremism, the foundation of Tilak's political and social thought was undeniably shaped by Ranade's mentorship. Ranade's emphasis on social reform, constitutional methods, and education provided Tilak with a framework that he would later adapt and expand upon. In this sense, Mahadev Govind Ranade's role as Tilak's political guru was instrumental in molding one of India's most influential freedom fighters and thinkers. Their relationship underscores the importance of intellectual mentorship in the broader struggle for India's independence and social transformation.

Can Political Parties Legally Purchase Land? Exploring Ownership Rules

You may want to see also

Swami Vivekananda's Impact: Vivekananda's influence on Tilak's nationalism and spiritual-political vision

Swami Vivekananda’s profound influence on Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s nationalism and spiritual-political vision cannot be overstated. Tilak, often regarded as the "Father of Indian Unrest," credited Vivekananda as his political guru, a title that underscores the transformative impact of the Swami’s ideas on Tilak’s worldview. Vivekananda’s emphasis on the revival of India’s spiritual heritage and his call for self-reliance and national awakening deeply resonated with Tilak. The Swami’s assertion that India’s strength lay in its ancient Vedic traditions and its ability to harmonize spirituality with action provided Tilak with a philosophical foundation for his political activism. This spiritual-political synthesis became the cornerstone of Tilak’s ideology, enabling him to mobilize the masses with a sense of pride in their cultural identity.

Vivekananda’s teachings on the inherent power of the individual and the nation left an indelible mark on Tilak’s approach to nationalism. The Swami’s famous declaration at the Chicago Parliament of Religions in 1893, where he introduced Hinduism as a universal religion of strength and tolerance, inspired Tilak to reframe Indian nationalism as a movement rooted in spiritual self-confidence. Tilak adopted Vivekananda’s idea that true freedom was not just political but also spiritual, psychological, and cultural. This holistic understanding of freedom shaped Tilak’s campaigns, such as the Ganapati and Shivaji festivals, which were designed to foster a sense of unity and pride among the people while subtly challenging British colonial authority.

Another critical aspect of Vivekananda’s influence was his emphasis on the practical application of spiritual ideals. Vivekananda believed that spirituality should not be confined to monasteries but should manifest in social and political action. Tilak internalized this principle, translating it into his slogan, "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it." He saw the struggle for independence as a sacred duty, a dharma, inspired by Vivekananda’s teachings on karma yoga, which advocates selfless action as a path to liberation. This spiritual framing of political struggle gave Tilak’s movement a moral gravitas and motivated ordinary Indians to participate in the freedom fight.

Vivekananda’s critique of passive resistance and his advocacy for strength—both physical and moral—also shaped Tilak’s militant nationalism. The Swami’s words, "Arise, awake, and stop not till the goal is reached," became a rallying cry for Tilak and his followers. Unlike the moderate approach of pleading with the British, Tilak adopted a more aggressive stance, demanding unconditional self-rule. This shift in strategy was directly influenced by Vivekananda’s belief that true freedom required courage, resilience, and a refusal to compromise on one’s principles. Tilak’s uncompromising attitude and his willingness to face imprisonment for his beliefs were a testament to this Vivekananda-inspired ethos.

Finally, Vivekananda’s vision of a resurgent India, free from colonial subjugation and united in its diversity, provided Tilak with a long-term goal for his political endeavors. Tilak’s efforts to bridge the gap between the elite and the masses, his emphasis on education, and his use of cultural symbols to unite people across regions and castes were all inspired by Vivekananda’s inclusive and holistic vision of India. The Swami’s belief that India’s future depended on its ability to modernize without abandoning its spiritual core became the guiding principle of Tilak’s nationalism. In this way, Swami Vivekananda was not just Tilak’s political guru but also the architect of his spiritual-political vision, which continues to inspire generations in India’s freedom struggle and beyond.

Are Political Parties Beneficial or Detrimental to Democracy?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bal Gangadhar Tilak's Self-Education: His independent study of politics, philosophy, and revolutionary ideas

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a seminal figure in India's independence movement, was not merely a political leader but also a self-educated intellectual whose independent study of politics, philosophy, and revolutionary ideas shaped his ideology and actions. Unlike many of his contemporaries who received formal education in Western institutions, Tilak’s intellectual growth was largely self-directed. He immersed himself in a wide array of subjects, drawing from both Eastern and Western traditions to forge a unique worldview. His self-education was characterized by a relentless curiosity and a commitment to understanding the roots of societal and political issues, which later became the foundation of his revolutionary thought.

Tilak’s study of politics was deeply influenced by his analysis of India’s colonial condition. He independently explored the works of Western political thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Edmund Burke, but he also critically examined their ideas in the context of Indian realities. His engagement with political philosophy led him to conclude that India’s liberation required not just political change but a cultural and spiritual awakening. This realization was further solidified by his study of ancient Indian texts, which he believed held the key to India’s identity and strength. Tilak’s self-education in politics was thus a synthesis of Western political theory and Indian philosophical traditions, enabling him to articulate a vision of swaraj (self-rule) that resonated with the masses.

Philosophically, Tilak was deeply influenced by his study of Vedanta and the Bhagavad Gita, which he saw as repositories of timeless wisdom. His independent exploration of these texts led him to develop the concept of "karma yoga," or the path of selfless action, as a guiding principle for revolutionary struggle. Tilak’s philosophical self-education was not confined to spirituality; he also delved into the works of thinkers like Herbert Spencer and Karl Marx, though he remained critical of their materialist perspectives. This eclectic approach allowed him to craft a philosophy that emphasized both individual duty and collective liberation, making his ideas accessible and inspiring to a diverse audience.

Tilak’s revolutionary ideas were the culmination of his self-education in politics and philosophy. He independently studied the histories of revolutions, from the American War of Independence to the French Revolution, drawing lessons on the role of mass mobilization and the importance of cultural unity. His analysis of these events, combined with his understanding of India’s colonial exploitation, led him to advocate for a more aggressive approach to independence. Tilak’s famous declaration, "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it," was not just a political slogan but a reflection of his deeply studied conviction that freedom was inseparable from India’s cultural and spiritual heritage.

In essence, Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s self-education was a transformative journey that equipped him with the intellectual tools to challenge colonial rule and inspire a nation. His independent study of politics, philosophy, and revolutionary ideas was marked by a unique ability to bridge Eastern and Western thought, creating a framework that was both radical and rooted in tradition. Tilak’s legacy as a political guru lies not just in his leadership but in his demonstration of how self-education can empower individuals to shape history. His life and work remain a testament to the power of intellectual curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge as acts of resistance and revolution.

Understanding Political Geography: Shaping Borders, Power, and Global Dynamics

You may want to see also

Intellectual Peers and Debates: Tilak's interactions with contemporaries that refined his political philosophy

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a seminal figure in India's independence movement, was profoundly influenced by his interactions with intellectual contemporaries, whose debates and discussions refined his political philosophy. One of his most significant intellectual peers was Mahadev Govind Ranade, a social reformer and scholar. Ranade advocated for gradual reform within the British system, emphasizing education and social upliftment. Tilak, however, diverged sharply from Ranade's moderate approach, championing a more radical, nationalist stance. Their debates on the pace and methods of reform were pivotal in shaping Tilak's belief in the necessity of mass mobilization and cultural resurgence as tools for political awakening. Ranade's emphasis on Western education and legal reform contrasted with Tilak's focus on indigenous traditions and self-rule, highlighting the tension between reformism and revolution in late 19th-century India.

Another critical figure in Tilak's intellectual circle was Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a moderate leader who prioritized constitutional methods and economic reforms. Gokhale's belief in working within the British framework to achieve incremental change clashed with Tilak's advocacy for swaraj (self-rule) and his call for direct confrontation with colonial authority. Their public debates, particularly during the Swarajya Fund controversy, underscored the ideological divide between moderates and extremists within the Indian National Congress. Gokhale's critique of Tilak's aggressive methods, including his support for armed resistance, forced Tilak to articulate and refine his arguments for a more assertive nationalist agenda. These interactions solidified Tilak's conviction that true independence required not just political but also cultural and economic self-reliance.

Tilak's engagement with Swami Vivekananda also played a transformative role in his political thought. Vivekananda's emphasis on India's spiritual heritage and his call for a synthesis of modern and traditional values resonated deeply with Tilak. This interaction inspired Tilak to integrate cultural nationalism into his political philosophy, as seen in his efforts to revive festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi and Shivaji Jayanti as platforms for public mobilization. Vivekananda's global perspective and his critique of Western materialism further reinforced Tilak's belief in the need for an indigenous, self-reliant political movement. Their shared vision of a resurgent India, rooted in its cultural ethos, became a cornerstone of Tilak's ideology.

Additionally, Tilak's interactions with Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, his fellow members of the Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate, were instrumental in shaping his revolutionary outlook. Rai's focus on Punjab and Pal's work in Bengal created a pan-Indian network of nationalist thought, with Tilak at its core. Their collective efforts to challenge British authority through public agitation and journalism amplified Tilak's ideas on self-rule and cultural pride. Debates within this group often centered on strategies for mass mobilization, with Tilak's emphasis on grassroots engagement and cultural symbolism proving particularly influential. These collaborations not only refined Tilak's political philosophy but also established him as a unifying figure in the nationalist movement.

Finally, Tilak's engagement with Annie Besant, the Irish theosophist and leader of the Home Rule League, introduced him to international perspectives on self-governance. While Besant's approach was more aligned with constitutional methods, her advocacy for Home Rule complemented Tilak's demands for swaraj. Their joint efforts in the Home Rule Movement demonstrated Tilak's ability to collaborate across ideological lines while staying true to his core principles. Besant's global connections and her support for India's spiritual heritage further validated Tilak's belief in the importance of cultural identity in the struggle for independence. These interactions with Besant and others underscored Tilak's role as a bridge between traditionalism and modernity in Indian political thought.

In conclusion, Tilak's intellectual peers and debates were instrumental in refining his political philosophy. Through his engagements with figures like Ranade, Gokhale, Vivekananda, Rai, Pal, and Besant, Tilak developed a nuanced understanding of the complexities of India's struggle for independence. These interactions not only sharpened his arguments for swaraj and cultural nationalism but also established him as a pivotal figure in the intellectual and political landscape of colonial India. His ability to synthesize diverse ideas and forge a cohesive nationalist ideology remains a testament to his legacy as a political thinker and leader.

Switching Political Parties: A Step-by-Step Guide to Changing Affiliation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bal Gangadhar Tilak's political guru is widely regarded to be Mahadev Govind Ranade, a prominent social reformer and scholar.

Ranade influenced Tilak's early understanding of social reform and political thought, though Tilak later diverged from Ranade's moderate views to adopt a more radical approach.

No, Tilak initially followed Ranade's moderate reformist ideas but later criticized them, advocating for more aggressive nationalist policies and self-rule.

Tilak and Ranade started as collaborators in social reform but eventually became ideological opponents, with Tilak emerging as a leader of the extremist faction in Indian nationalism.

Ranade's teachings provided Tilak with a foundation in political and social thought, which he later built upon to become a key figure in India's independence movement.