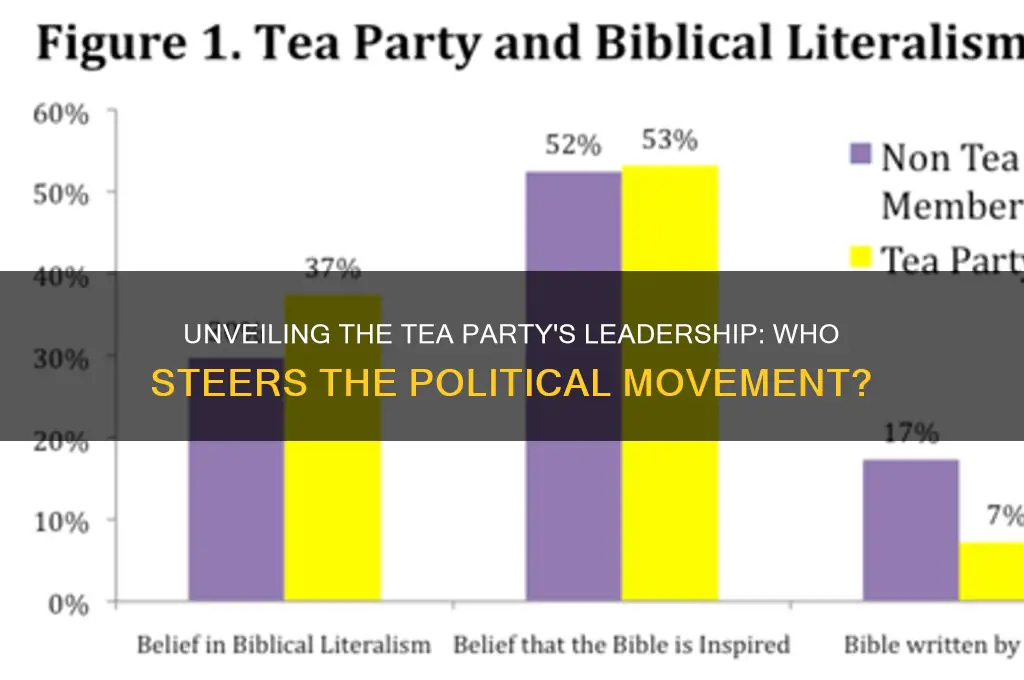

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the United States in 2009, is not a traditional political party with a centralized leadership structure but rather a loosely organized coalition of conservative activists, grassroots organizations, and individuals advocating for limited government, lower taxes, and adherence to the Constitution. As such, there is no single, officially recognized leader of the Tea Party. Instead, prominent figures such as former Congresswoman Michele Bachmann, Senator Ted Cruz, and media personalities like Glenn Beck and Sarah Palin have been influential voices within the movement. These individuals, along with local leaders and activists, have played key roles in shaping the Tea Party's agenda and mobilizing its supporters, though the movement's decentralized nature ensures no one person holds ultimate authority.

Explore related products

$27.44 $37

What You'll Learn

Origins of the Tea Party Movement

The Tea Party movement, often misunderstood as a monolithic entity, emerged from a tapestry of grassroots discontent rather than a single leader’s vision. Its origins trace back to the early 2000s, fueled by a growing unease with government spending, taxation, and what many perceived as federal overreach. The movement’s name, a nod to the 1773 Boston Tea Party, symbolized resistance to perceived tyranny, but its modern incarnation was less about tea and more about fiscal conservatism and limited government. Unlike traditional political parties, the Tea Party lacked a centralized hierarchy, instead relying on local chapters and charismatic figures to amplify its message.

One pivotal moment in the movement’s formation was the 2009 CNBC broadcast where Rick Santelli, a financial commentator, delivered an on-air rant against government bailouts. His call for a “Tea Party” to protest fiscal irresponsibility went viral, sparking rallies across the country. This event, though not the sole catalyst, crystallized the frustrations of many Americans and provided a rallying cry. However, it’s crucial to note that Santelli’s role was more of a spark than a sustained leadership position. The movement’s decentralized nature meant no single figure could claim sole ownership, though individuals like Sarah Palin, Ron Paul, and Michele Bachmann became prominent voices.

Analyzing the movement’s origins reveals a blend of economic anxiety and ideological fervor. The 2008 financial crisis and subsequent government interventions, such as the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), deepened public mistrust of Washington. Grassroots organizers, often using social media and local networks, mobilized supporters around issues like deficit reduction and opposition to the Affordable Care Act. This bottom-up approach allowed the Tea Party to resonate with diverse groups, from libertarians to social conservatives, despite lacking a unified platform. Practical tips for understanding this era include examining local Tea Party chapters’ activities and the role of conservative media in amplifying their message.

Comparatively, the Tea Party’s rise mirrors other populist movements in American history, such as the Populist Party of the late 19th century, which also emerged in response to economic hardship and perceived elite control. However, the Tea Party’s ability to leverage modern technology and media gave it a unique edge. For instance, platforms like Facebook and Twitter allowed organizers to coordinate nationwide protests with unprecedented speed. This digital mobilization underscores a key takeaway: the movement’s success was as much about timing and tools as it was about ideology.

In conclusion, the origins of the Tea Party movement are a study in decentralized activism and the power of shared grievances. While no single leader defined the movement, its impact on American politics—from reshaping the Republican Party to influencing policy debates—remains undeniable. Understanding its roots requires looking beyond individual figures to the broader cultural and economic forces that fueled its rise. For those interested in grassroots organizing, the Tea Party’s story offers valuable lessons in harnessing local energy and leveraging modern communication tools to drive national change.

Kansas Senators: Political Affiliations and Representation in the Senate

You may want to see also

Key Figures and Leaders in the Movement

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, is often characterized as a grassroots conservative movement rather than a traditional political party with a single leader. However, several key figures have played pivotal roles in shaping its ideology and influence. Among these, Senator Ted Cruz stands out as a prominent voice, known for his staunch advocacy of limited government and fiscal responsibility. Cruz’s 21-hour filibuster in 2013, aimed at defunding the Affordable Care Act, exemplifies the movement’s confrontational approach to policy. His ability to galvanize supporters through social media and public appearances underscores his leadership, even if unofficial, within the Tea Party’s broader coalition.

Another influential figure is Sarah Palin, the former governor of Alaska and 2008 vice-presidential candidate. Palin’s populist rhetoric and emphasis on "common sense conservatism" resonated deeply with Tea Party adherents. Her 2009 resignation as governor allowed her to focus on national activism, including endorsements of Tea Party candidates and frequent media appearances. While Palin’s role was more symbolic than organizational, her ability to articulate the movement’s frustrations with establishment politics cemented her status as a de facto leader.

Behind the scenes, Jim DeMint, former U.S. Senator from South Carolina, played a critical role in institutionalizing the Tea Party’s influence. As the founder of the Senate Conservatives Fund, DeMint provided financial and strategic support to Tea Party candidates, helping them challenge incumbent Republicans in primaries. His decision to leave the Senate in 2013 to lead the Heritage Foundation further solidified his role as a thought leader within the movement. DeMint’s focus on policy purity and his willingness to break with the GOP establishment made him a central figure in the Tea Party’s rise.

A comparative analysis reveals that while these leaders share core principles, their styles and contributions differ. Cruz’s leadership is marked by legislative activism, Palin’s by charismatic populism, and DeMint’s by strategic organization. Together, they illustrate the movement’s multifaceted nature, blending ideological rigor, grassroots appeal, and institutional influence. For those studying or engaging with the Tea Party, understanding these figures’ distinct roles provides a clearer picture of how the movement operates and sustains itself.

Finally, it’s essential to note that the Tea Party’s decentralized structure means no single individual can claim sole leadership. Instead, its strength lies in the collective impact of these key figures and countless local organizers. Practical engagement with the movement requires recognizing this dynamic—focusing on shared principles rather than a singular leader. This approach not only aligns with the Tea Party’s ethos but also offers a more effective strategy for influencing its trajectory.

Why Politics Fails: Ben Ansell's Insights on Governance Challenges

You may want to see also

Tea Party’s Political Ideology and Goals

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, is not a traditional political party with a single leader but rather a decentralized grassroots movement. Its ideology and goals are rooted in a desire to return to what adherents see as the founding principles of the United States: limited government, fiscal responsibility, and individual liberty. These principles are often distilled into three core tenets: lower taxes, reduced government spending, and minimal federal regulation. Unlike conventional parties, the Tea Party’s strength lies in its ability to mobilize local activists and influence Republican Party politics, often pushing candidates to adopt more conservative stances.

Analytically, the Tea Party’s ideology can be seen as a reaction to what its supporters perceive as government overreach, particularly during the Obama administration. Key events like the 2008 bank bailouts and the passage of the Affordable Care Act fueled their belief that federal power was expanding at the expense of individual freedoms and state rights. This ideology is deeply intertwined with a nostalgic view of America’s founding documents, such as the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, which they interpret as advocating for a strictly limited federal government. For instance, Tea Party activists often cite the Tenth Amendment, which reserves powers not granted to the federal government to the states or the people, as a cornerstone of their political philosophy.

Instructively, if you’re seeking to understand the Tea Party’s goals, consider their focus on tangible policy outcomes rather than abstract ideals. Their agenda includes repealing or replacing the Affordable Care Act, slashing federal spending on entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, and eliminating what they view as wasteful government agencies. Practical tips for engaging with Tea Party ideology include studying the works of economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, who heavily influence their free-market beliefs, and examining state-level policies in places like Texas and Florida, where Tea Party-aligned politicians have implemented their vision of limited government.

Persuasively, critics argue that the Tea Party’s ideology, while appealing in its simplicity, often oversimplifies complex issues. For example, their opposition to federal spending ignores the necessity of government investment in infrastructure, education, and healthcare to maintain societal well-being. Moreover, their emphasis on state rights can lead to inconsistent policies across the country, creating disparities in areas like voting rights and environmental protection. However, proponents counter that this approach ensures local communities retain control over their affairs, fostering innovation and accountability.

Comparatively, the Tea Party’s goals align closely with those of libertarianism but differ in their emphasis on social conservatism. While libertarians prioritize personal freedoms across all issues, including social ones like drug legalization and same-sex marriage, the Tea Party often aligns with religious conservatives on these topics. This hybrid ideology—fiscally conservative and socially traditional—sets them apart from both mainstream Republicans and libertarians. For instance, while they advocate for reducing federal taxes, they are less likely to support policies like marijuana legalization, even if it aligns with a limited government philosophy.

Descriptively, the Tea Party’s influence is most evident in its ability to shape Republican primaries and congressional agendas. By mobilizing grassroots support, they have successfully challenged establishment candidates and pushed issues like the federal debt ceiling and government shutdowns into the national spotlight. Their rallies, often featuring Gadsden flags and slogans like “Taxed Enough Already,” serve as visual symbols of their resistance to what they see as an overbearing federal government. This movement’s enduring legacy lies in its role as a watchdog, constantly pressuring politicians to adhere to conservative fiscal principles, even if it means gridlock in Washington.

Fox News' Political Leanings: Uncovering the Network's Conservative Slant

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$53.19 $72.99

Impact on Republican Party and Elections

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, significantly reshaped the Republican Party by injecting a strong dose of fiscal conservatism and anti-establishment sentiment into its platform. This shift was evident in the 2010 midterm elections, where Tea Party-backed candidates like Rand Paul and Marco Rubio secured key Senate seats, signaling a new era of grassroots influence within the GOP. These victories were not just wins for individual candidates but a clear message that the Republican base demanded smaller government, lower taxes, and reduced federal spending. The movement’s ability to mobilize voters and challenge incumbent Republicans in primaries forced the party to recalibrate its priorities, often at the expense of moderate voices.

However, the Tea Party’s impact on the Republican Party was a double-edged sword. While it energized the base and delivered electoral successes in the short term, it also contributed to internal divisions and ideological rigidity. The movement’s uncompromising stance on issues like the debt ceiling and Obamacare led to high-stakes showdowns in Congress, such as the 2013 government shutdown. These events alienated independent voters and created a perception of Republican obstructionism, which Democrats effectively leveraged in subsequent elections. The party’s struggle to balance Tea Party demands with broader electoral appeal became a defining challenge of the 2010s.

To understand the Tea Party’s electoral impact, consider its role in shaping the 2012 Republican presidential primary. Candidates like Michele Bachmann and Rick Perry initially courted Tea Party support, but their campaigns faltered due to missteps and a lack of broad appeal. Mitt Romney, the eventual nominee, faced skepticism from Tea Party activists who viewed him as insufficiently conservative. This dynamic highlights a critical takeaway: while the Tea Party could propel candidates to victory in primaries, its influence sometimes hindered general election success by pushing nominees too far to the right for moderate voters.

Practical lessons from the Tea Party’s rise include the importance of grassroots organizing and the risks of ideological purity. For Republican strategists, the movement underscores the need to balance base enthusiasm with messaging that resonates beyond the party’s core. For instance, focusing on economic issues like job creation and tax reform, which unite conservatives and independents, can mitigate the polarizing effects of more extreme positions. Additionally, candidates should avoid alienating demographic groups, such as younger voters or minorities, who are often turned off by the Tea Party’s rhetoric.

In conclusion, the Tea Party’s impact on the Republican Party and elections is a study in both power and peril. It demonstrated the potential of grassroots movements to reshape political landscapes but also revealed the challenges of sustaining such influence without alienating broader electorates. As the GOP continues to navigate its identity in the post-Tea Party era, the lessons from this movement remain highly relevant, offering both a roadmap and a cautionary tale for future electoral strategies.

Understanding Syria's Political Freedoms: Challenges, Restrictions, and Human Rights Concerns

You may want to see also

Current Status and Influence of the Tea Party

The Tea Party, once a dominant force in conservative politics, has seen its influence wane in recent years. A search for its current leader yields no clear, singular figure, reflecting the movement’s decentralized nature and diminished organizational cohesion. Unlike traditional political parties, the Tea Party has always been more of a grassroots coalition, making leadership roles fluid and often tied to prominent figures rather than formal titles. Today, its lack of a central leader underscores its shift from a headline-grabbing movement to a more diffuse ideological influence within the Republican Party.

Analyzing its current status reveals a movement that has largely been absorbed into the broader conservative ecosystem. The Tea Party’s core principles—limited government, fiscal responsibility, and opposition to taxation—remain influential, but they are now championed by individual politicians and factions rather than a unified group. Figures like Senator Rand Paul and Representative Thomas Massie occasionally invoke Tea Party rhetoric, but their alignment is more symbolic than organizational. This integration into mainstream conservatism has diluted the Tea Party’s distinct identity, making it harder to pinpoint its boundaries or measure its independent impact.

To understand the Tea Party’s influence today, consider its role in shaping the Republican Party’s agenda. During the Obama administration, the Tea Party drove the GOP’s hardline stance on issues like the debt ceiling and healthcare reform. Now, its legacy is evident in the party’s continued emphasis on tax cuts, deregulation, and skepticism of federal power. However, this influence is often indirect, as the movement’s energy has been channeled into broader conservative priorities rather than distinct Tea Party initiatives. Practical examples include the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which aligned with Tea Party principles but was spearheaded by the Trump administration and congressional Republicans.

A cautionary note is warranted when assessing the Tea Party’s current relevance. While its organizational structure may be weakened, its ideological footprint persists in the rise of populist conservatism. The movement’s emphasis on anti-establishment sentiment and grassroots activism laid the groundwork for phenomena like the Trump presidency and the Freedom Caucus. Yet, this evolution also highlights the Tea Party’s challenge: its success in mainstreaming its ideas has come at the cost of its distinct identity. For those seeking to revive or emulate the movement, the takeaway is clear—focus on mobilizing local communities and leveraging digital platforms to amplify messages, as the Tea Party did in its heyday.

In conclusion, the Tea Party’s current status is one of ideological endurance rather than organizational dominance. Its influence is felt in the Republican Party’s policy priorities and the broader conservative movement’s anti-establishment ethos. While it lacks a clear leader or centralized structure, its legacy continues to shape American politics. For activists and observers alike, the Tea Party serves as a case study in the power and pitfalls of grassroots movements—a reminder that ideas can outlast organizations, even as they evolve in unpredictable ways.

Alexander Hamilton's Perspective on Political Parties: Unity vs. Division

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Tea Party is not a formal political party with a centralized leadership structure. It is a grassroots movement with various local and national leaders, but no single individual serves as its official leader.

No, the Tea Party does not have a national chairman or spokesperson. It operates as a decentralized movement, with different groups and individuals representing its principles.

Prominent figures associated with the Tea Party include politicians like Senator Ted Cruz, former Congresswoman Michele Bachmann, and media personalities such as Glenn Beck and Sarah Palin.

There is no single organization that represents the entire Tea Party movement. It consists of numerous independent groups, each with its own leadership and focus.

The Tea Party relies on local activism and consensus-building among its members. Decisions are often made at the grassroots level, with coordination among various groups rather than top-down leadership.