The question of who automatically assumes leadership of a political party is a nuanced one, varying significantly across different political systems and party structures. In some cases, the leader is elected by party members or delegates during a formal leadership contest, while in others, the position may be inherited through a hierarchical succession process, such as when a deputy or high-ranking official steps in following a vacancy. Certain parties may also have constitutional provisions that outline specific criteria or roles that automatically confer leadership, such as being the party’s candidate for a top governmental position, like prime minister or president. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial, as they not only shape the internal dynamics of a party but also influence its external representation and policy direction.

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Historical Precedents: Examines past instances of automatic leadership succession within political parties globally

- Constitutional Rules: Explores party constitutions defining automatic leadership roles and their legal implications

- Deputy Leaders: Analyzes the role of deputy leaders as automatic successors in leadership vacuums

- Emergency Protocols: Discusses temporary automatic leadership assumptions during crises or leader incapacitation

- Family Dynasties: Investigates hereditary or familial automatic leadership traditions in certain political parties

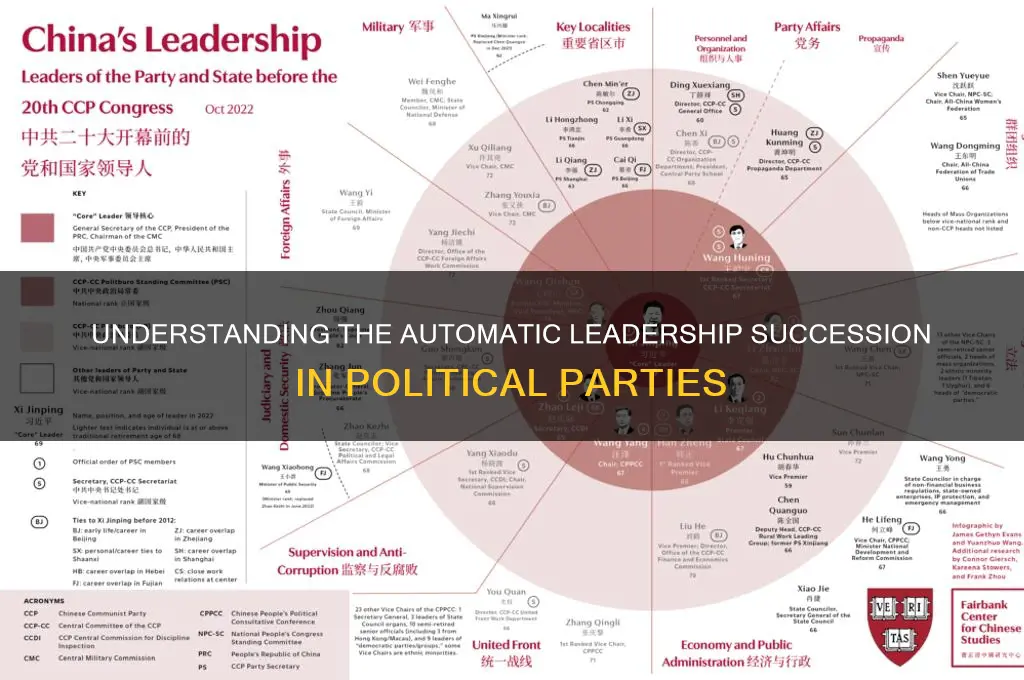

Historical Precedents: Examines past instances of automatic leadership succession within political parties globally

The concept of automatic leadership succession within political parties is not a modern invention but a practice rooted in historical precedents. One of the earliest and most notable examples is the Liberal Party of the United Kingdom in the 19th century. During this period, the party often looked to its most prominent and experienced figures to assume leadership roles without formal contests. For instance, William Ewart Gladstone became the de facto leader due to his stature as a former Prime Minister and his dominance in parliamentary debates, rather than through a structured election process. This informal succession set a precedent for leadership based on merit and recognition within the party ranks.

In contrast, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union provides a starkly different example of automatic succession. Here, leadership was often transferred based on hierarchical positioning and ideological alignment with the party’s central committee. When Joseph Stalin succeeded Vladimir Lenin in the 1920s, it was not through a democratic process but through his strategic consolidation of power within the party apparatus. This model highlights how automatic succession can be manipulated to serve authoritarian ends, emphasizing the importance of transparency and accountability in leadership transitions.

A more contemporary example is the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, where leadership succession has historically followed a predictable pattern. For instance, Thabo Mbeki succeeded Nelson Mandela as party leader and president in 1999, a transition that was widely anticipated due to Mbeki’s role as deputy president and his alignment with the party’s ideological direction. This case illustrates how automatic succession can be a stabilizing force in post-colonial or transitional democracies, provided it reflects the will of the party membership.

Analyzing these precedents reveals a critical takeaway: the success of automatic leadership succession hinges on legitimacy and consensus. In the UK Liberal Party, Gladstone’s succession was accepted because he embodied the party’s values and had proven leadership capabilities. In the Soviet Union, Stalin’s rise lacked legitimacy due to its coercive nature, leading to long-term instability. The ANC’s model, while more orderly, has faced challenges in recent years as internal factions have contested the automatic succession of leaders like Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa. This underscores the need for clear rules and inclusive processes, even in systems that favor automatic succession.

To implement automatic succession effectively, political parties should adopt three key steps: first, establish transparent criteria for leadership eligibility, such as tenure, ideological alignment, or electoral success. Second, foster internal democracy by allowing members to ratify the successor, ensuring broad acceptance. Third, create mechanisms for accountability, such as term limits or performance reviews, to prevent the concentration of power. By learning from historical precedents, parties can design succession systems that balance stability with legitimacy, ensuring smooth transitions and sustained public trust.

Finding Your Political Home: Which Party Truly Represents Your Values?

You may want to see also

Constitutional Rules: Explores party constitutions defining automatic leadership roles and their legal implications

Political parties often embed automatic leadership succession rules within their constitutions to ensure stability and continuity during transitions. These rules typically designate a specific role—such as the deputy leader, general secretary, or most senior elected official—to assume leadership temporarily or permanently in the event of a vacancy. For instance, the Labour Party in the UK stipulates that the deputy leader automatically becomes acting leader if the leader resigns, dies, or is incapacitated. This constitutional clarity prevents power vacuums and internal disputes, allowing the party to function effectively during crises.

Analyzing these constitutional provisions reveals their legal implications, particularly in jurisdictions where party leadership affects parliamentary or governmental roles. In countries like Germany, where party leaders often head parliamentary factions, automatic succession rules must align with parliamentary procedures to ensure legitimacy. For example, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) constitution mandates that the deputy leader assumes the role of parliamentary leader until a new leader is elected, ensuring compliance with Bundestag rules. Failure to adhere to such legal frameworks can lead to challenges in courts or legislative bodies, undermining the party’s authority.

Instructively, parties drafting or amending their constitutions should consider three key elements: clarity, inclusivity, and adaptability. Clarity ensures that the succession process is unambiguous, reducing the risk of internal disputes. Inclusivity involves consulting diverse party factions to ensure the rule reflects the organization’s values. Adaptability allows for adjustments to unforeseen circumstances, such as leadership disputes or external legal changes. For example, the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa includes a provision for an interim leadership committee if the automatic successor is unable to assume the role, demonstrating a balanced approach.

Comparatively, automatic leadership rules vary widely across political systems. In presidential systems like the United States, parties often lack formal constitutional rules, relying instead on informal norms or state-level primaries. In contrast, parliamentary systems like India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have detailed constitutional provisions, with the party president automatically becoming the prime ministerial candidate in some cases. This divergence highlights the importance of aligning constitutional rules with the broader political and legal context to ensure their effectiveness.

Persuasively, the legal implications of these rules extend beyond internal party dynamics to public trust and democratic integrity. When automatic succession is mishandled—as seen in Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF during Robert Mugabe’s ouster—it can lead to constitutional crises and erode public confidence. Parties must therefore treat their constitutions as living documents, regularly reviewed and updated to reflect evolving legal standards and societal expectations. By doing so, they not only safeguard their own stability but also contribute to the health of the democratic systems in which they operate.

Joining the Political Arena: A Step-by-Step Guide to Party Membership

You may want to see also

Deputy Leaders: Analyzes the role of deputy leaders as automatic successors in leadership vacuums

Deputy leaders often serve as the linchpin in political parties, poised to step into the top role during leadership vacuums. Their position is not merely ceremonial; it is a strategic placement designed to ensure continuity and stability. In many parties, the deputy leader is the automatic successor, bypassing the need for immediate internal elections or power struggles. This arrangement is particularly crucial in times of crisis, such as the sudden resignation, incapacitation, or death of the leader. For instance, in the UK Labour Party, the deputy leader assumes interim leadership until a new leader is elected, ensuring the party remains functional during transitions.

The role of the deputy leader as an automatic successor is both a privilege and a burden. On one hand, it grants them significant influence and visibility, often positioning them as the heir apparent. On the other hand, it requires them to be perpetually prepared to lead, demanding a deep understanding of party dynamics, policy, and public sentiment. Take the example of the Australian Labor Party, where the deputy leader is not only a standby leader but also a key figure in shaping party strategy and coalition-building. This dual responsibility underscores the need for deputies to balance loyalty to the current leader with readiness to take charge.

However, the automatic succession model is not without risks. It can stifle internal competition and limit the emergence of new leadership talent, as the deputy may be perceived as the inevitable next leader. This was evident in the Liberal Democrats of the UK, where the deputy’s automatic ascension led to accusations of stifling fresh voices. To mitigate this, parties often implement term limits or require deputies to stand for election alongside other candidates when the leadership position becomes vacant. Such measures ensure that automatic succession does not equate to unchallenged dominance.

Practical tips for deputy leaders include cultivating a distinct leadership style while aligning with the party’s core values, building alliances across factions, and maintaining a public profile that complements rather than overshadows the current leader. For instance, in Canada’s Conservative Party, deputies often take on high-profile policy portfolios to demonstrate their capability without appearing overly ambitious. Additionally, deputies should engage in scenario planning, preparing for various leadership vacuum scenarios, from planned transitions to emergencies.

In conclusion, deputy leaders as automatic successors play a critical role in maintaining party cohesion during leadership vacuums. Their effectiveness hinges on a delicate balance of preparedness, loyalty, and strategic positioning. While the model ensures stability, it requires careful management to avoid entrenching power and stifling innovation. Parties must design roles and succession processes that leverage the deputy’s strengths while fostering a healthy leadership pipeline.

Mastering Political Party Adjustments in Florida: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Emergency Protocols: Discusses temporary automatic leadership assumptions during crises or leader incapacitation

In times of crisis or sudden leadership vacuums, political parties often rely on predefined emergency protocols to ensure continuity and stability. These protocols typically designate a temporary automatic leader, whose role is to maintain party cohesion and operational functionality until a permanent successor is chosen. The identity of this interim leader varies widely across parties and nations, but common positions include the deputy leader, party secretary, or the most senior member of the party’s executive committee. For instance, in the United Kingdom’s Conservative Party, the deputy leader or the most senior cabinet minister often assumes temporary control if the leader is incapacitated.

Analyzing these protocols reveals a delicate balance between expediency and legitimacy. The automatic assumption of leadership must be swift to prevent power struggles or operational paralysis, yet it must also align with the party’s internal hierarchy to maintain credibility among members and the public. In some cases, this temporary leader is explicitly outlined in the party’s constitution, while in others, it is an unwritten convention based on precedent. For example, Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has a clear succession plan, with the general secretary often stepping in during emergencies, ensuring minimal disruption.

However, the effectiveness of these protocols hinges on their clarity and acceptance within the party. Ambiguity in succession rules can lead to internal disputes, as seen in some African political parties where rival factions contest the legitimacy of interim leaders. To mitigate this, parties should regularly review and communicate their emergency protocols, ensuring all members understand the chain of command. Additionally, incorporating feedback from diverse party factions can enhance the protocol’s perceived fairness and reduce the risk of internal conflict.

A comparative analysis of emergency leadership protocols across democracies highlights both commonalities and unique adaptations. In presidential systems like the United States, the vice president automatically assumes power if the president is incapacitated, a principle enshrined in the Constitution. In contrast, parliamentary systems often rely on party-specific rules, which can vary significantly. For instance, Canada’s Liberal Party designates the deputy leader as the interim leader, while Australia’s Labor Party may turn to the deputy prime minister or the most senior cabinet member. These differences underscore the importance of tailoring protocols to the specific political and cultural context of each party and nation.

In conclusion, emergency leadership protocols are a critical yet often overlooked aspect of political party governance. They serve as a safeguard against chaos during crises, ensuring that parties can continue to function effectively even in the absence of their primary leader. By combining clarity, legitimacy, and adaptability, these protocols can provide a stable bridge to permanent leadership transitions, preserving both party unity and public trust. Parties that invest in robust, well-communicated emergency plans are better equipped to navigate unforeseen challenges and maintain their relevance in turbulent times.

Unveiling Frank Menetrez's Political Affiliation: Which Party Does He Represent?

You may want to see also

Family Dynasties: Investigates hereditary or familial automatic leadership traditions in certain political parties

In some political parties, leadership is not earned through democratic processes but inherited through bloodlines, creating family dynasties that dominate the party's structure for generations. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in countries with strong familial ties and less emphasis on meritocracy. For instance, the Nehru-Gandhi family in India has been at the helm of the Indian National Congress for decades, with leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and Sonia Gandhi all belonging to the same lineage. Similarly, the Bhutto family in Pakistan has played a pivotal role in the Pakistan Peoples Party, with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto, and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari all serving as prominent leaders.

The mechanics of hereditary leadership often involve a carefully orchestrated transfer of power from one family member to another, typically upon the incumbent's retirement, death, or incapacitation. This transition is usually justified by appealing to the family's historical legacy, emotional connections with the party base, and the perceived continuity of the party's ideology. However, this system can stifle internal competition, discourage fresh ideas, and perpetuate a culture of entitlement. Critics argue that such dynasties undermine democratic principles by limiting opportunities for talented individuals outside the family circle.

To understand the implications of family dynasties, consider the following steps: first, examine the party's constitution or bylaws for clauses that explicitly or implicitly favor familial succession. Second, analyze the party's leadership history to identify patterns of hereditary leadership. Third, assess the impact of these dynasties on the party's performance, voter engagement, and policy outcomes. For example, while family dynasties can provide stability and a recognizable brand, they may also lead to policy stagnation and alienation of younger, more progressive members.

A comparative analysis reveals that family dynasties are more common in parties with strong personality-driven cultures, such as the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, where the Abe and Koizumi families have been influential. In contrast, parties with robust internal democratic mechanisms, like the Labour Party in the UK, tend to avoid hereditary leadership. This comparison underscores the importance of institutional design in preventing the concentration of power within a single family. Parties seeking to break free from dynastic traditions should consider reforms such as term limits, open primaries, and mandatory leadership elections.

Finally, while family dynasties can offer advantages like name recognition and emotional appeal, they also pose significant risks to democratic governance. To mitigate these risks, parties should prioritize transparency, accountability, and inclusivity in their leadership selection processes. Practical tips include fostering mentorship programs for non-dynastic members, encouraging grassroots participation, and regularly auditing the party's leadership practices. By doing so, parties can strike a balance between honoring their historical legacies and embracing the principles of meritocracy and equality.

Will the Political Left Endure in a Shifting Global Landscape?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no universal rule for an automatic leader of a political party. Leadership is typically determined through internal party elections, consensus, or established procedures outlined in the party's constitution.

While founders often assume leadership roles initially, it is not automatic. Leadership must still be formalized through party processes, such as elections or appointments, depending on the party's rules.

Seniority does not automatically confer leadership. Leadership is usually determined by election, appointment, or other mechanisms specified in the party's bylaws, regardless of a member's tenure.

No, winning the most votes in a general election does not automatically make someone the party leader. Party leadership is separate from electoral success and is decided through internal party processes.