The US Constitution outlines two types of officers: inferior officers and superior officers. Inferior officers are those who have permanent positions with significant authority and are appointed by the President, the Judiciary, or Heads of Departments (within the Executive branch). Superior officers, on the other hand, are appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate and must not have a superior other than the President. The distinction between these two types of officers has been a subject of debate and interpretation by various courts over time, with a shift in focus from appointment methods and tenure to the duties and discretion accompanying each office. The interpretation of who is a superior officer has evolved, with a modern focus on the authority and decision-making capacity of the position.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Appointment | Superior officers are appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate |

| Superior | A superior officer must lack a superior other than the President |

| Role | A superior officer has the capacity to make policy decisions |

| Position | Superior officers hold permanent positions |

| Authority | Superior officers have significant authority |

| Military | Military officers are considered officers of the U.S. |

| Civilian | Civilian officers are issued written commissions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The US President is a superior officer

In addition to their role as Commander-in-Chief, the President is also considered a civilian officer of the US. The original public meaning of "officer" is broader than modern doctrine assumes, encompassing any government official with responsibility for an ongoing governmental duty. In the 19th century, the President of the United States was considered an officer by the public. In the case of K&D LLC v. Trump Old Post Office, LLC, President Trump successfully argued that the President of the United States qualifies as an officer, and the court agreed.

The President's role as an officer has been further supported by the Colorado Supreme Court, which ruled in December 2023 that the President is an officer of the United States as pertains to Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. This ruling raised the question of whether the President is an officer, with textualists and originalists offering different interpretations.

The President's position as a superior officer is also reflected in their power to appoint other officers. The President appoints ambassadors, ministers, consuls, Supreme Court judges, and all other officers of the United States, with the advice and consent of the Senate. However, Congress may vest the appointment of inferior officers in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

The President's status as a superior officer is further emphasized by their inclusion in the presidential line of succession. Several officers of the United States are empowered to become acting President if neither the President nor the Vice President can discharge their functions. This highlights the significant authority wielded by the President as a superior officer in the constitutional framework of the United States.

Understanding Bids and Offers: Requesting Bids and Their Nature

You may want to see also

Superior officers are appointed by the President with Senate consent

The U.S. Constitution makes a distinction between "inferior" and "superior" officers, with different requirements for their appointment. Superior officers are those who are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, according to Article II, § 2, cl. 2 of the Constitution, also known as the Appointments Clause. This clause authorises the President to "nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, ... appoint ... all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for".

The Appointments Clause further allows Congress to vest the appointment of inferior officers in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments. Inferior officers are those whose work is directed and supervised by others appointed by presidential nomination with the advice and consent of the Senate. They must have permanent positions and significant authority, and they must also have a superior officer other than the President.

The distinction between inferior and superior officers is important as it determines the process by which they are appointed. The Supreme Court has considered various factors in determining whether an officer is inferior or superior, including the tenure, duration, and duties of the position. For example, in Edmond v. United States, the Supreme Court considered whether judges of the Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals were principal or inferior officers. The Court held that these judges were inferior officers because they lacked the power to render final decisions on behalf of the United States without permission from other executive officers.

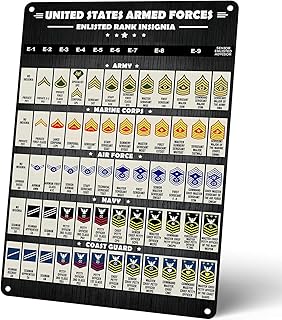

In addition to civilian officers, persons who hold military commissions are also considered officers of the United States. The President, as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, has the authority to delegate command to military officers. Furthermore, in the 19th century, the President of the United States was considered an officer by the public due to the broader original public meaning of the term "officer". However, the modern interpretation of "officer" is narrower and typically refers to government officials with specific responsibilities.

Banding Together: WWII's Musical Unifiers

You may want to see also

Inferior officers are appointed by the President, judiciary, or department heads

The U.S. Constitution establishes a clear distinction between principal and inferior officers, with different requirements for their appointment. While principal officers are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, inferior officers are those whose appointment Congress may vest in the President alone, in the judiciary, or in the heads of departments. This distinction is important as it ensures a separation of powers between Congress's power to create offices and the President's authority to nominate officers.

The Appointments Clause, outlined in Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution, provides the framework for this two-tiered system. It states that "all Officers of the United States" must be appointed by the President with the Senate's advice and consent, unless Congress specifies otherwise for inferior officers. This clause has been interpreted and refined through various Supreme Court cases, such as Buckley v. Valeo, Edmond v. United States, and Morrison v. Olson, which have shaped the understanding of who constitutes an "officer."

The Supreme Court has shifted its focus over time, initially emphasizing the method of appointment and tenure before moving towards a more functional analysis of an official's duties and discretion. This evolution is reflected in cases like Landry v. FDIC and Buckley v. Valeo, where the Court applied a broader interpretation of "officer" beyond just the method of appointment. The Court's current interpretation considers an officer to be "any appointee exercising significant authority pursuant to the laws of the United States."

The distinction between principal and inferior officers is not always clear-cut, as seen in cases like Morrison v. Olson and Edmond v. United States, where individuals with superiors were still considered principal officers. This complexity underscores the dynamic nature of constitutional interpretation and the ongoing refinement of the Appointments Clause.

In summary, the U.S. Constitution's framework for appointing officers involves two tiers, with inferior officers being appointed by the President alone, the judiciary, or department heads, while principal officers require the additional advice and consent of the Senate. This system balances Congress's power to create offices with the President's authority to nominate officers, ensuring a measure of accountability in the staffing of important government positions.

The Iraqi Constitution: Ratification and Its Process

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Superior officers can make policy decisions

The US Constitution makes a distinction between inferior and superior officers, with the former being subject to the latter. Superior officers are those who are appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate, whereas inferior officers can be appointed by the President, the Judiciary, or Heads of Departments within the Executive branch.

The distinction between inferior and superior officers is important as the Constitution provides different requirements for their appointment. One key factor in distinguishing between the two types of officers is whether they have the capacity to make policy decisions. Superior officers are those who have the power to make policy decisions, while inferior officers are constrained in their role and lack the authority to formulate federal policy.

For example, in the case of Morrison v. Olson, the Court found that the independent counsel was an inferior officer because, among other factors, they lacked the authority to formulate federal policy and were limited to investigating and prosecuting specific federal crimes. Similarly, in United States v. Arthrex, Inc., the Court held that administrative patent judges were inferior officers because they lacked the power to render unreviewable decisions, which indicated that they were subject to a superior officer.

In the military context, a superior officer is one who has the authority to command the armed forces of the United States. Even the lowest-ranking military or naval officer can be considered a potential commander of US armed forces in combat, especially if their superiors suffer casualties. The officer's authority to command is derived from the President as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States".

In summary, superior officers in the US Constitution are those who have the capacity to make policy decisions and are not subject to a superior other than the President. They are appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate and have significant authority within their sphere of influence.

The Constitution's Provisions: What Does It Provide?

You may want to see also

Military officers are considered officers of the US

The US Constitution makes a distinction between “principal” and “inferior” officers, with the former referring to those who are not subordinate to a department head, and the latter referring to those whose work is supervised and directed by others. The US President is considered the principal officer and is responsible for appointing all other officers, whether superior or inferior, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

In addition to civilian officers, persons who hold military commissions are also considered officers of the US. While this is not explicitly defined in the Constitution, it is implied in its structure. Military judges, for example, have been deemed inferior officers by the Supreme Court. The authority of military officers to command the armed forces of the United States is derived from the President, who is the "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States".

The distinction between officers and employees of the United States rests on whether the office held has been explicitly delegated a part of the "sovereign power of the United States". This delegation of "sovereign power" refers to the authority to commit the federal government to legal obligations, such as signing contracts, executing treaties, interpreting laws, or issuing military orders. Federal judges, for instance, have been delegated a portion of this "sovereign power".

There has been debate over whether the President should be considered an officer of the United States. While some argue that the President is not constitutionally an officer, others point to the Appointments Clause and the broader original public meaning of "officer", which includes any government official with ongoing governmental duties.

Core Principles of Constitutional Democracy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A superior officer is an official who has been appointed by the President with the consent of the Senate. They do not have a superior other than the President and have the capacity to make policy decisions.

An inferior officer is an official who is appointed by the President, the Judiciary, or Heads of Departments (within the Executive branch). They must have a superior other than the President and do not have the capacity to make policy decisions.

An employee has a temporary position or a position that lacks significant authority. An officer, on the other hand, has a permanent position and wields significant authority.

In Freytag v. Commissioner, the Supreme Court held that special trial judges, appointed for life, were inferior officers.

In December 2023, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. President is an officer of the United States as per Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. This ruling is significant as it led to Donald Trump's disqualification from the ballot for the 2024 Colorado Republican primary.