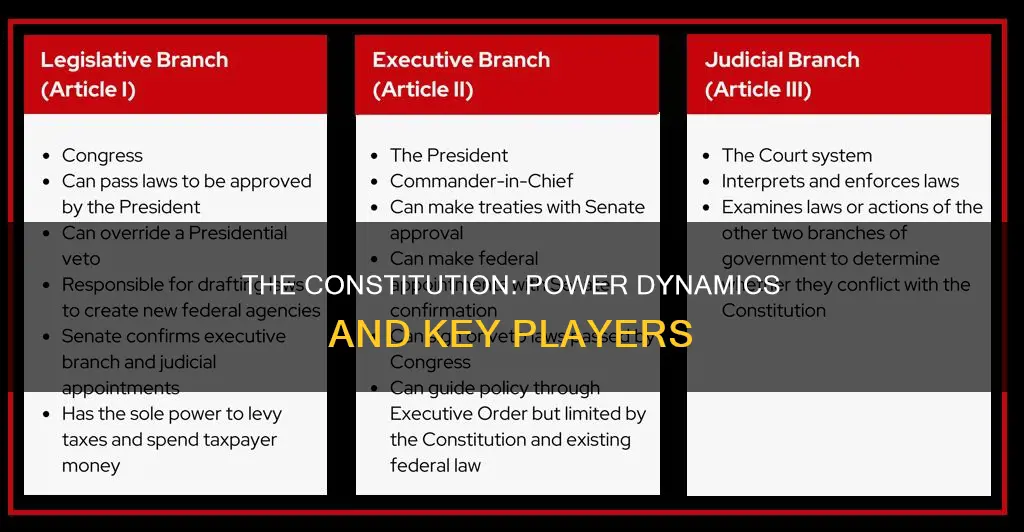

The U.S. Constitution was a federal constitution that was influenced by the European Enlightenment thinkers of the eighteenth century, such as Montesquieu and John Locke, and documents such as the Magna Carta. The Constitution was drafted by a committee appointed by the Second Continental Congress in June 1777 and was adopted in mid-November of the same year. Ratification by the 13 colonies was completed on March 1, 1781. The Constitution establishes the Executive Branch of the federal government, with the executive power vested in the President of the United States. The President has powers such as the ability to grant reprieves and pardons, receive ambassadors, and enforce laws. However, the President's power is not absolute and can be checked by Congress, with the consent of two-thirds of the Senators. The Constitution also outlines the election of the President, including the establishment of the electoral college, and sets out qualifications, such as being a natural-born citizen and at least 35 years old.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The President's role as Commander-in-Chief

The U.S. Constitution designates the President as the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Navy, and Militia of the United States. This role, as outlined in Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the Constitution, grants the President significant authority over the country's military and foreign relations.

The Commander-in-Chief role of the President has been a subject of debate and interpretation over the years. The Constitution's intention was to ensure civilian control over the military and to place that control in the hands of a single person, the President. This provision was included in response to concerns under the Declaration of Independence that the military could become independent of and superior to civilian power.

The President, as Commander-in-Chief, holds prime responsibility for the conduct of United States foreign relations. This includes the power to make executive decisions regarding military actions, such as in the case of the war in Indochina. However, the extent of the President's war powers has been a matter of discussion, with some arguing for a broader interpretation of the Commander-in-Chief clause to include strong and unilateral domestic war powers.

In contrast, others emphasize the role of Congress in providing checks and balances on the President's military authority. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, for example, requires express authorization from Congress before the military can be used in domestic law enforcement. Additionally, Congress has the power to regulate the militia and provide for their calling forth in times of domestic emergency. This interpretation underscores the importance of maintaining civilian control over the military and preventing the concentration of power in a single individual.

The Commander-in-Chief role of the President is a critical aspect of their position, shaping both foreign policy and the dynamic between the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government. While the President holds significant authority as Commander-in-Chief, the Constitution also provides mechanisms to ensure that this power is balanced and accountable to the people.

Money Laundering Act: Constitutional Basis Explained

You may want to see also

Presidential pardons and clemency

The U.S. Constitution grants the President the power to grant reprieves, pardons, and clemency for federal offences, except in cases of impeachment. This power is outlined in Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the Constitution. While the President's power to pardon has been challenged in court and by Congress, the courts have consistently upheld the President's discretion in this matter.

The President's pardon power allows them to reverse a criminal conviction, effectively treating it as if it never happened. Pardons can also be offered for a specific period, covering any crimes committed during that time or preventing any charges from ever being filed.

Throughout history, several notable individuals have received presidential pardons or clemency. For example, President John F. Kennedy pardoned 575 people, including first-time offenders convicted under the Narcotics Control Act of 1956 and Hank Greenspun, who was convicted of violating the Neutrality Act in 1950. President Ronald Reagan pardoned 406 people, including FBI officials Mark Felt and Edward S. Miller, and former Maryland governor Marvin Mandel.

More recently, President Biden has granted pardons and clemency to several individuals, including former Secret Service agent Abraham Bolden, Venezuelans Franqui Flores and Efrain Antonio Campo Flores as part of a prisoner exchange, and 6,500 people convicted of simple marijuana possession.

The Constitution: Black Lives Under White Rule

You may want to see also

Congress's implied powers

The concept of implied powers, first articulated by Alexander Hamilton, refers to powers that Congress possesses that are not explicitly enumerated in the U.S. Constitution. These powers are derived from the Taxing and Spending Clause, the Necessary and Proper Clause, and the Commerce Clause. They are also known as "elastic clauses" because they give the Constitution flexibility.

The question of Congress's implied powers first arose during President George Washington's administration, when Congress proposed chartering a national bank. The power to charter a bank is not specifically granted to Congress in the Constitution, but Hamilton argued that Congress had the implied power to adopt any means useful to carrying out its enumerated powers. He said that the bank would be useful for executing Congress's war powers, which required paying troops and transferring funds.

Jefferson and Randolph disagreed, arguing that additional congressional power should not be implied unless it was absolutely necessary to the exercise of an enumerated power. Otherwise, they warned, Congress would effectively have unlimited power.

In the 1819 McCulloch v. Maryland case, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with Hamilton's interpretation. Chief Justice John Marshall held that the Constitution's grant of enumerated powers to Congress included the means of making their exercise effective. He argued that the Necessary and Proper Clause did not limit Congress's implied powers to those that were absolutely necessary for executing its enumerated powers. Instead, it was enough that the means chosen by Congress were convenient or useful.

The McCulloch decision settled that the scope of Congress's implied powers is very broad. Combined with the broad nature of some of Congress's enumerated powers, such as the power to tax and spend for the general welfare and the power to regulate interstate commerce, there is very little that is beyond the power of the national government to regulate.

One example of Congress's implied powers in action is its plenary power over immigration, which has been the subject of several modern Supreme Court cases.

Amendments to the Constitution: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$49.99 $52.99

The Vice President's role

The role of vice president of the United States has undergone several changes since the position was first established by the Constitution. Initially, the vice presidency held very little power and had limited duties. The vice president's primary role was to serve as president of the Senate, maintaining order, recognizing members to speak, and interpreting the Senate's rules. They were also given the power to take over the "powers and duties" of the presidency in the event of the president's removal, death, resignation, or inability to discharge their powers and duties. However, it was unclear whether the vice president would actually become the president or simply act as one in such cases.

The ambiguity surrounding the vice president's role was first tested in 1841, following the death of President William Henry Harrison. Harrison's vice president, John Tyler, asserted that he had succeeded to the presidency, not just to its powers and duties. He had himself sworn in as president and refused to acknowledge documents referring to him as "Acting President". Despite opposition from some in Congress, Tyler's view ultimately prevailed, setting a precedent that a vice president assumes the full title and role of president upon the death, resignation, or removal from office of their predecessor.

The Twenty-fifth Amendment, ratified in 1967, further clarified the vice president's role in presidential vacancies and inability or disability of the president. The amendment formalized the Tyler Precedent, stating that the vice president becomes president in such cases. It also allowed the president to notify Congress of their inability to discharge their duties, with the vice president acting as president until the president resumes their duties. Additionally, the amendment addressed the process of filling a vacancy in the office of vice president, allowing the president to nominate a successor with confirmation by a majority vote in both houses of Congress.

Today, the vice presidency is widely considered a position of significant power and an integral part of the president's administration. The vice president serves as a key advisor, governing partner, and representative of the president. They are also a statutory member of important bodies such as the National Security Council. While the exact nature of the role varies depending on the relationship between the president and vice president, the vice president's power primarily flows from delegations of authority from the president and Congress.

Exploring Congress' Powers: Understanding Constitutional Boundaries

You may want to see also

The President's role in foreign relations

The Office of the Chief of Protocol advises, assists, and supports the President, Vice President, and Secretary of State on matters of national and international protocol. This includes planning and officiating ceremonies and activities for visiting heads of state and coordinating travel for the President and Vice President. The Secretary of State, under the President's direction, is responsible for coordinating and supervising U.S. government activities abroad.

While the President has significant power in foreign relations, it is important to note that their power is balanced by Congress, which can pass laws affecting foreign policy and control federal spending. Judicial oversight also plays a role, with federal courts assessing the constitutionality of foreign policy actions and treaties.

In conclusion, the President's role in foreign relations is a powerful one, with the ability to shape global alliances, direct military strategies, and address contemporary global challenges. However, this power is balanced by the other branches of government to prevent unilateral decisions and ensure collaboration in U.S. foreign policy.

Texas' Constitutional Transformations: How Many Versions?

You may want to see also

![Founding Fathers [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71f9-HsS5nL._AC_UY218_.jpg)