The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a notorious white supremacist group, was founded in 1865 by six former Confederate soldiers in Pulaski, Tennessee, including Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became its first Grand Wizard. While the KKK is not a formal political party, it has historically exerted significant political influence, particularly in the post-Civil War South, by promoting racist ideologies and opposing civil rights for African Americans. Its members have often infiltrated political systems, aligning with or influencing parties that supported segregation and white supremacy, though it remains primarily a hate group rather than a recognized political entity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Nathan Bedford Forrest |

| Birthdate | July 13, 1821 |

| Death | October 29, 1877 |

| Occupation | Confederate General, Slave Trader, Ku Klux Klan Leader |

| Role in KKK | First Grand Wizard (national leader) |

| Year KKK Founded | December 24, 1865 |

| Location of Founding | Pulaski, Tennessee, USA |

| Initial Purpose | Resist Reconstruction policies, maintain white supremacy |

| Notable Actions | Led early KKK activities, including violence against African Americans and Republicans |

| Later Disavowal | Claimed to have abandoned the KKK in 1869, though the extent of his continued involvement is debated |

| Historical Legacy | Controversial figure, criticized for his role in the KKK and slave trading, but also remembered by some for his military tactics |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of the KKK: Founded in 1865 by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, after the Civil War

- Key Founders: Led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general, and five other ex-soldiers

- Initial Goals: Aimed to resist Reconstruction and maintain white supremacy in the South

- Political Influence: Evolved into a political force, backing Democratic candidates and opposing civil rights

- Modern Resurgence: Revived in 1915 by William J. Simmons, focusing on anti-immigration and racism

Origins of the KKK: Founded in 1865 by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, after the Civil War

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) emerged in the turbulent aftermath of the American Civil War, founded in 1865 by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee. This secretive organization was born out of a desire to resist Reconstruction efforts and maintain white supremacy in the defeated South. The founders, disillusioned by the loss of their Confederate cause and fearful of the newfound freedoms granted to formerly enslaved African Americans, sought to restore their perceived social order through intimidation and violence. Pulaski, a small town with a history of antebellum wealth and Confederate loyalty, provided the perfect breeding ground for such a movement. The KKK’s origins were rooted in resentment, racism, and a refusal to accept the political and social changes sweeping the nation.

Analyzing the motivations of the KKK’s founders reveals a complex interplay of personal, political, and economic factors. Confederate veterans, stripped of their status and privileges, felt betrayed by the federal government’s Reconstruction policies. The Klan’s early activities—nighttime raids, masked gatherings, and acts of terror—were designed to undermine the progress of African Americans and their white allies. By targeting schools, churches, and political leaders, the Klan aimed to suppress Black political participation and enforce racial segregation. This systematic campaign of fear was not merely a reaction to defeat but a calculated effort to reshape the South according to their vision of white dominance.

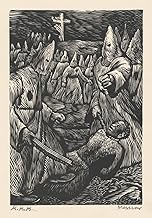

To understand the KKK’s rapid spread, consider its organizational structure and appeal to disaffected Southerners. The Klan operated as a fraternal order, complete with rituals, titles, and a hierarchy that mimicked military ranks. This structure provided a sense of belonging and purpose to veterans struggling to reintegrate into civilian life. Local chapters, known as “klaverns,” sprang up across the South, each operating with autonomy but united by a shared ideology. The Klan’s secretive nature and use of symbolism—hoods, robes, and fiery crosses—added an air of mystique, attracting members who sought both camaraderie and a means to exert control in a changing society.

A comparative look at the KKK’s origins highlights its divergence from other post-war organizations. While groups like the Freemasons or veterans’ associations focused on mutual aid and community building, the Klan’s mission was explicitly violent and exclusionary. Unlike legitimate political parties, the KKK operated outside the law, using terror as a tool to achieve its goals. This distinction is crucial: the Klan was not merely a political party but a paramilitary organization that sought to subvert democracy. Its founding in Pulaski marked the beginning of a dark chapter in American history, one that continues to influence racial tensions today.

Practically speaking, the KKK’s origins serve as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked hatred and the manipulation of fear. For educators, historians, and activists, understanding the Klan’s roots in Pulaski provides insight into the conditions that allow such groups to flourish. By studying the economic, social, and political climate of post-Civil War Tennessee, we can identify parallels in contemporary society. Efforts to combat modern hate groups must address the underlying grievances that fuel their rise, whether economic insecurity, cultural displacement, or racial resentment. The KKK’s founding reminds us that vigilance and education are essential to preventing history from repeating itself.

Mike Duggan's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Key Founders: Led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general, and five other ex-soldiers

The Ku Klux Klan, a group notorious for its white supremacist ideology and acts of violence, was founded in the aftermath of the American Civil War. At its helm was Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general whose military tactics were as controversial as his post-war activities. Alongside Forrest were five other ex-Confederate soldiers, each bringing their own experiences and grievances to the nascent organization. This core group of founders laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most infamous hate groups in American history.

Forrest’s leadership was pivotal, not only because of his military reputation but also due to his ability to galvanize disillusioned Southerners. As a former slave trader and plantation owner, Forrest embodied the economic and social anxieties of the post-war South. His role in the Klan’s formation was both strategic and symbolic, representing a resistance to Reconstruction and the enfranchisement of African Americans. The other five founders, though less well-known, were instrumental in organizing local chapters and spreading the Klan’s ideology across Tennessee and beyond. Their collective military background ensured a disciplined structure, while their shared resentment of the federal government fueled the group’s radical agenda.

To understand the Klan’s origins, it’s essential to examine the historical context in which Forrest and his compatriots operated. The South was in ruins, both physically and psychologically, and many ex-soldiers felt betrayed by the North’s imposition of Reconstruction policies. The Klan emerged as a secretive, vigilante response to these changes, targeting not only African Americans but also Northern sympathizers and anyone perceived as a threat to the old order. Forrest’s leadership lent the group a veneer of legitimacy, despite its violent and illegal activities. His infamous quote, “We’ll ride again,” captured the defiant spirit of the Klan’s early years.

While Forrest is often credited as the Klan’s primary founder, the contributions of the other five ex-soldiers should not be overlooked. Their identities—John W. Morton, James R. Crowe, J.D. Kennedy, Frank McCord, and Richard Reed—are less remembered today, but their roles were crucial in the Klan’s early expansion. Morton, for instance, was instrumental in drafting the Klan’s constitution, which outlined its hierarchical structure and oaths of secrecy. Crowe and Kennedy focused on recruitment, leveraging their military networks to attract members. McCord and Reed, meanwhile, were key figures in organizing the Klan’s first public demonstrations, which often involved cross-burnings and parades designed to intimidate local communities.

In practical terms, the Klan’s founding was a calculated effort to restore white supremacy through fear and violence. Forrest and his fellow founders understood the power of symbolism, adopting hoods and robes to conceal their identities while amplifying their menace. This tactic not only protected members from legal repercussions but also created an aura of omnipresence, as if the Klan could strike anywhere at any time. For those seeking to understand the group’s enduring legacy, studying its origins under Forrest and his five co-founders provides critical insights into how hate groups exploit historical grievances to mobilize followers.

Global Power Players: The World's Most Influential Political Parties

You may want to see also

Initial Goals: Aimed to resist Reconstruction and maintain white supremacy in the South

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) emerged in the aftermath of the American Civil War, a period marked by the Reconstruction era’s efforts to rebuild the South and integrate formerly enslaved African Americans into society. Founded in 1865 by six former Confederate officers in Pulaski, Tennessee, the KKK’s initial goals were explicitly tied to resisting Reconstruction policies and preserving white supremacy. This resistance took the form of violent intimidation, aimed at suppressing Black political participation, dismantling newly established civil rights, and restoring pre-war racial hierarchies. Their tactics included lynchings, arson, and voter suppression, all designed to terrorize Black communities and their white allies.

Analytically, the KKK’s objectives were a direct response to the societal shifts brought by Reconstruction. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, which abolished slavery, granted citizenship, and ensured voting rights to Black men, threatened the South’s traditional power structures. The Klan viewed these changes as an existential threat to white dominance, framing their actions as a defense of Southern culture and heritage. However, this narrative was a thinly veiled attempt to justify racial oppression and maintain control over a rapidly changing social landscape. Their efforts were not merely reactionary but strategically organized to undermine federal authority and local governments that supported equality.

Instructively, understanding the KKK’s initial goals requires examining their methods. Members targeted Black leaders, educators, and politicians, often with impunity, due to sympathetic local law enforcement and judicial systems. For instance, the Klan’s campaign against Black schools and churches aimed to stifle educational and economic progress, ensuring that African Americans remained in positions of subservience. Practical insights into this period reveal how systemic racism was enforced through extralegal violence, creating a climate of fear that persisted long after Reconstruction ended.

Persuasively, the KKK’s resistance to Reconstruction highlights the fragility of progress in the face of entrenched ideologies. Despite federal efforts to protect Black rights, the Klan’s widespread influence demonstrated the limits of legislative change without societal transformation. This historical example underscores the importance of addressing both legal and cultural systems of oppression. Modern movements for racial justice often grapple with similar challenges, as remnants of white supremacist ideologies continue to shape institutions and attitudes.

Comparatively, the KKK’s goals align with other historical movements that sought to preserve racial hierarchies through violence and intimidation. From South Africa’s apartheid regime to the Jim Crow era in the United States, these groups shared a common playbook: using terror to enforce inequality. However, the KKK’s direct opposition to Reconstruction distinguishes it as a uniquely American phenomenon, rooted in the nation’s unresolved contradictions around race and democracy. This comparison reveals the recurring patterns of resistance to racial progress and the enduring need for vigilance against such forces.

Cassie Franklin's Political Party: Uncovering Her Affiliation and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Influence: Evolved into a political force, backing Democratic candidates and opposing civil rights

The Ku Klux Klan's transformation into a political force in the early 20th century was marked by its strategic alignment with the Democratic Party, particularly in the South. This alliance was not merely coincidental but rooted in shared opposition to civil rights for African Americans. By backing Democratic candidates, the KKK sought to preserve white supremacy and resist federal interventions that threatened Jim Crow laws. This period saw the Klan wielding significant influence over local and state politics, often through intimidation and violence, to ensure their preferred candidates secured office.

To understand the Klan's political strategy, consider its grassroots approach. Local chapters mobilized voters, distributed propaganda, and even ran Klan members as candidates for public office. In states like Alabama and Indiana, Klansmen openly campaigned on platforms of racial segregation and anti-immigration, resonating with a fearful white electorate. The Democratic Party, at the time the dominant political force in the South, often turned a blind eye to these activities, as Klan-backed candidates helped maintain their grip on power. This symbiotic relationship allowed the KKK to infiltrate political institutions and shape policy from within.

A cautionary tale emerges when examining the Klan's success in the 1920s. Their ability to disguise bigotry as patriotism and leverage economic anxieties for political gain highlights the dangers of unchecked extremism. For instance, the Klan's anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant rhetoric found fertile ground during a time of rapid social change, appealing to those who felt left behind. Modern political movements can learn from this history: addressing legitimate grievances without resorting to division is crucial to preventing the rise of hate groups.

Practical steps to counter such political influence include fostering civic education that emphasizes inclusivity and critical thinking. Communities must remain vigilant against dog-whistle politics and hold leaders accountable for their associations. Additionally, supporting legislation that protects civil rights and promotes equality is essential to dismantling systemic racism. By learning from the Klan's historical tactics, society can build resilience against similar movements in the future.

In conclusion, the KKK's evolution into a political force underscores the fragility of democratic institutions when confronted with organized hatred. Their backing of Democratic candidates and opposition to civil rights serve as a stark reminder of the consequences of political complacency. By studying this dark chapter, we equip ourselves with the knowledge to recognize and resist efforts to undermine equality, ensuring a more just and inclusive society.

Understanding Europe's Green Party: Core Political Views and Goals

You may want to see also

Modern Resurgence: Revived in 1915 by William J. Simmons, focusing on anti-immigration and racism

The Ku Klux Klan, a specter of America's racist past, experienced a chilling revival in 1915 under the leadership of William J. Simmons. This resurgence wasn't merely a nostalgic reenactment; it was a calculated rebranding, harnessing the anxieties of a nation grappling with rapid social change. Simmons, a former Methodist preacher, understood the power of fear and scapegoating. He tapped into growing anti-immigrant sentiment, fueled by the influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans, and stoked racial tensions, exploiting the lingering wounds of Reconstruction.

This new Klan wasn't just about hoods and torches. Simmons, a shrewd organizer, transformed it into a national fraternity, complete with elaborate rituals, titles, and a hierarchical structure. He marketed it as a patriotic, Christian organization dedicated to preserving "100% Americanism," a code phrase for white supremacy. This veneer of respectability allowed the Klan to attract millions of members, including prominent politicians, law enforcement officers, and even clergy.

Simmons' Klan wasn't just about rhetoric; it was about action. They employed intimidation tactics, from cross burnings and parades to violent attacks on African Americans, Catholics, Jews, and immigrants. Their influence extended beyond individual acts of terror; they sought to infiltrate local governments, influence legislation, and shape public opinion. The Klan's resurgence coincided with the rise of restrictive immigration laws, like the Immigration Act of 1924, which severely limited immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, reflecting the Klan's xenophobic agenda.

While Simmons himself was eventually ousted from leadership in 1922, the damage was done. The Klan's revival had reignited a flame of hatred that continues to flicker in the dark corners of American society. Understanding this chapter in history is crucial. It serves as a stark reminder of how fear and prejudice can be manipulated for political gain, and how seemingly respectable facades can mask dangerous ideologies.

To combat such resurgences, we must remain vigilant against hate speech, challenge xenophobic narratives, and actively promote inclusivity and equality. History has shown us the consequences of complacency; it's our responsibility to ensure that the Klan's toxic legacy remains firmly in the past.

The Rise of the Republicans: Whigs' Political Successor Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was not founded as a formal political party but as a white supremacist hate group. It was established in 1865 by six former Confederate veterans, including Nathan Bedford Forrest, who is often considered the first Grand Wizard.

No, the KKK has never been officially recognized as a political party in the United States. However, it has influenced politics through its members and affiliated groups, particularly in the South during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Yes, during the 1920s, the second iteration of the KKK had significant influence within the Democratic Party, particularly in Southern states. Some politicians, such as Hugo Black and Robert Byrd, had past affiliations with the KKK before their political careers.

The KKK was revived in 1915 by William J. Simmons, who reorganized the group after the release of the film *The Birth of a Nation*. This revival led to the KKK's peak membership in the 1920s.

While the KKK itself is not a political party, individual members have run for office under various party affiliations or as independents. Some were elected, particularly in local and state positions, during periods of heightened KKK influence.

![The Chamber [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/7175tS7nx4L._AC_UY218_.jpg)