The Tea Party political movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, primarily drew its base from a coalition of conservative activists, libertarians, and disaffected Republicans who were united by their opposition to government spending, taxation, and what they perceived as federal overreach. This grassroots movement was fueled by widespread dissatisfaction with the economic policies of the Obama administration, particularly the bank bailouts and stimulus packages. Core supporters included middle-class Americans, small business owners, and evangelical Christians, many of whom were mobilized through social media, local meetings, and high-profile events like the Tax Day protests of 2009. While the movement lacked a centralized leadership, it was significantly influenced by organizations like FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, as well as media personalities such as Glenn Beck and Sean Hannity, who amplified its message and galvanized its base.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Predominantly white, middle-aged to older adults |

| Political Affiliation | Strongly conservative, mostly Republican or Republican-leaning independents |

| Education Level | Mixed, but a significant portion with some college education or less |

| Income Level | Middle-class, with a focus on economic concerns like taxes and government spending |

| Geographic Location | Suburban and rural areas, particularly in the South and Midwest |

| Ideological Beliefs | Limited government, fiscal conservatism, opposition to government intervention, and a strong emphasis on individual liberty |

| Key Issues | Opposition to Obamacare, government bailouts, and perceived government overreach; support for lower taxes and reduced government spending |

| Organizational Structure | Grassroots, decentralized, with local chapters and national coordinating groups like the Tea Party Patriots |

| Media Influence | Strongly influenced by conservative media outlets like Fox News and talk radio |

| Historical Context | Emerged in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the election of President Obama, and the passage of the Affordable Care Act |

| Activism Style | Highly engaged in protests, town hall meetings, and political campaigns, often using social media for mobilization |

| Religious Affiliation | Predominantly Christian, with a significant portion identifying as evangelical or conservative Christian |

| Views on Social Issues | Generally socially conservative, though the movement's primary focus is on fiscal and economic issues |

| Perception of Government | Deep skepticism of federal government, often viewing it as too large, intrusive, and inefficient |

| Long-term Impact | Influenced the Republican Party's shift further to the right and played a role in the 2010 midterm elections, contributing to GOP gains in Congress |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Disaffected Conservatives: Frustrated with government spending and perceived overreach, they sought smaller government and fiscal responsibility

- Libertarian Influence: Emphasized individual liberty, limited government, and free markets, aligning with Tea Party principles

- Grassroots Activists: Local organizers mobilized communities through rallies, town halls, and social media campaigns

- Ron Paul Supporters: His 2008 campaign energized a base focused on constitutional governance and economic freedom

- Corporate Backing: Groups like FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity provided funding and organizational support

Disaffected Conservatives: Frustrated with government spending and perceived overreach, they sought smaller government and fiscal responsibility

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, was fueled by a diverse coalition of activists, but at its core were disaffected conservatives who felt betrayed by what they saw as unchecked government expansion and fiscal irresponsibility. These individuals, often lifelong Republicans, grew disillusioned with their party’s leadership for failing to adhere to principles of limited government and balanced budgets. Their frustration was not merely ideological but deeply personal, rooted in a sense that their tax dollars were being squandered on bloated programs and bailouts that benefited special interests rather than the average American.

To understand their mindset, consider the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent government response. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and the auto industry bailout, which collectively cost taxpayers hundreds of billions of dollars, became lightning rods for their anger. For these conservatives, such interventions represented a dangerous precedent: government overreach into the private sector, rewarding failure, and burdening future generations with debt. Their rallying cry for fiscal responsibility was not just about balancing the budget but about restoring a sense of fairness and accountability in governance.

Practically, these disaffected conservatives organized through grassroots efforts, leveraging social media and local meetings to amplify their message. They advocated for specific policy changes, such as a balanced budget amendment, spending cuts, and the elimination of wasteful programs. For instance, they targeted earmarks—those small, often obscure provisions in legislation that fund pet projects—as symbols of Washington’s out-of-control spending habits. By focusing on tangible examples of waste, they made their case accessible to a broader audience, turning abstract economic principles into actionable grievances.

However, their approach was not without challenges. While their demands for smaller government resonated with many, they often clashed with the realities of political compromise. For example, their opposition to tax increases, even on the wealthiest Americans, put them at odds with pragmatic solutions to reduce the deficit. This rigidity sometimes alienated potential allies and limited their influence within the broader conservative movement. Yet, their unwavering commitment to fiscal discipline forced a national conversation about the role and size of government, reshaping the Republican Party’s priorities in the process.

In retrospect, the disaffected conservatives who formed the base of the Tea Party movement were not merely protesters but architects of a political shift. Their frustration with government spending and perceived overreach gave rise to a renewed focus on fiscal responsibility, influencing elections, legislation, and public discourse. While their methods and priorities remain subjects of debate, their impact on American politics is undeniable. For those seeking to understand the movement’s legacy, studying their demands and strategies offers valuable insights into the enduring tension between idealism and pragmatism in governance.

Mark A. Thiel's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

Libertarian Influence: Emphasized individual liberty, limited government, and free markets, aligning with Tea Party principles

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, was a grassroots political phenomenon that drew from a variety of ideological sources. Among these, libertarianism played a significant role in shaping its core principles. Libertarians, who advocate for maximal individual liberty, minimal government intervention, and free markets, found common ground with many Tea Party activists. This alignment was not merely coincidental but rooted in shared concerns about government overreach, fiscal irresponsibility, and the erosion of personal freedoms. By emphasizing these principles, libertarians helped crystallize the Tea Party’s identity as a movement opposed to big government and in favor of economic and personal autonomy.

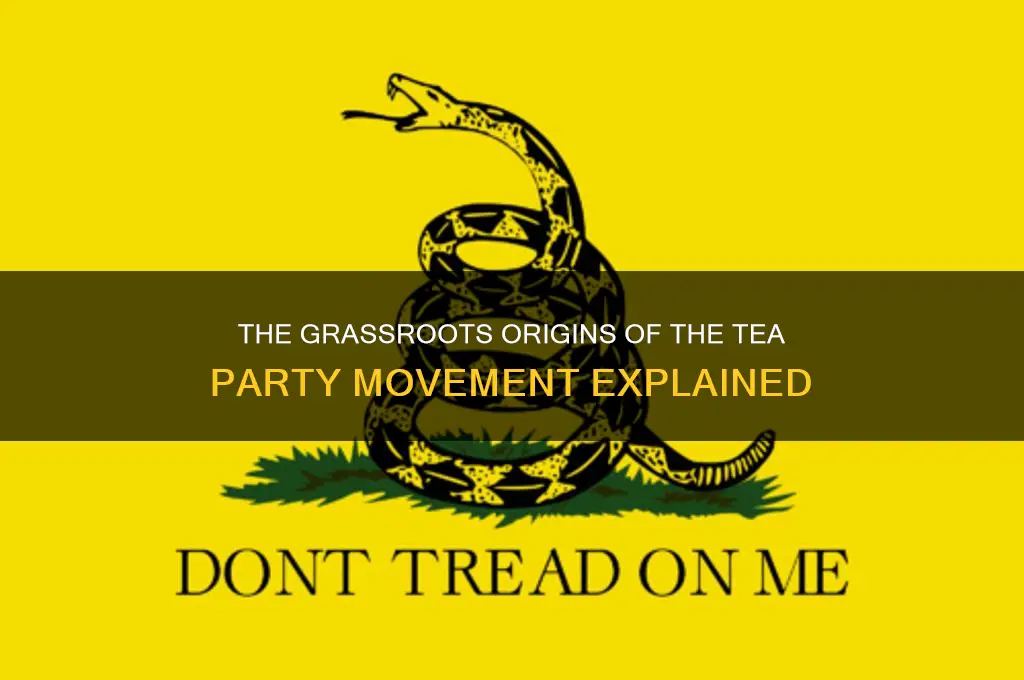

To understand the libertarian influence, consider the movement’s rallying cries: "Don’t Tread on Me" and "Taxed Enough Already." These slogans encapsulate libertarian ideals of resisting government intrusion and promoting fiscal restraint. For instance, libertarians argue that lower taxes and reduced regulation are essential for economic growth, a stance mirrored in the Tea Party’s opposition to bailouts and stimulus packages during the 2008 financial crisis. This shared economic philosophy was not just theoretical but practical, as seen in the movement’s support for balanced budgets and opposition to deficit spending. Activists often cited libertarian thinkers like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, whose works emphasize the dangers of centralized power and the virtues of free markets.

However, the libertarian influence on the Tea Party was not without tension. While both groups championed limited government, libertarians traditionally advocate for social liberties, such as drug legalization and LGBTQ+ rights, which did not always align with the socially conservative views of many Tea Party members. This divergence highlights the complexity of the movement’s base, where libertarian principles were adopted selectively. For example, while libertarians might oppose government involvement in personal choices, many Tea Party activists focused more on economic freedoms than social ones. This pragmatic adaptation allowed libertarian ideas to resonate widely, even among those who did not fully embrace the libertarian worldview.

Practical tips for understanding this dynamic include examining key events like the 2010 midterm elections, where Tea Party candidates often ran on platforms of cutting government spending and reducing regulations—hallmarks of libertarian thought. Additionally, studying the role of organizations like the Cato Institute and FreedomWorks, which promoted libertarian policies, provides insight into how these ideas were disseminated. For those interested in the movement’s evolution, comparing the Tea Party’s early focus on fiscal issues with its later incorporation of social conservatism offers a nuanced view of libertarian influence. By focusing on these specifics, one can see how libertarian principles were both a driving force and a point of contention within the Tea Party.

In conclusion, the libertarian influence on the Tea Party was profound, shaping its emphasis on individual liberty, limited government, and free markets. While not all Tea Party members identified as libertarians, the movement’s core principles were undeniably aligned with libertarian ideals. This alignment was instrumental in mobilizing a broad coalition of activists concerned about government overreach and fiscal irresponsibility. By examining the intersection of libertarianism and the Tea Party, we gain a clearer understanding of how ideological currents can shape political movements, even when those currents are not uniformly adopted. This analysis underscores the enduring impact of libertarian thought on American politics and its role in defining the Tea Party’s legacy.

Nigeria's Political Beginnings: The First Two Parties Explored

You may want to see also

Grassroots Activists: Local organizers mobilized communities through rallies, town halls, and social media campaigns

The Tea Party movement, which emerged in the late 2000s, was fueled by a groundswell of local organizers who harnessed the power of grassroots activism. These individuals, often ordinary citizens with no prior political experience, became the backbone of the movement by mobilizing communities through rallies, town halls, and social media campaigns. Their efforts transformed local discontent into a national force, demonstrating how decentralized leadership could amplify political voices.

Consider the mechanics of their mobilization: local organizers began by identifying shared grievances within their communities, such as government spending, taxation, and perceived overreach. They then leveraged low-cost, high-impact tools like Facebook groups, Twitter hashtags, and email chains to spread their message. For instance, a single town hall meeting in a small Midwestern town could be live-streamed and shared across state lines, inspiring similar gatherings elsewhere. This viral approach allowed the movement to grow exponentially, with each organizer acting as a node in a vast network of activism.

Rallies played a pivotal role in this strategy, serving as both a rallying cry and a visual testament to the movement’s strength. Organizers often partnered with local businesses or used public spaces to host events, keeping costs minimal while maximizing attendance. For example, a rally in Boston’s Boston Common drew thousands by combining patriotic symbolism with speeches from local leaders, creating a sense of unity and purpose. These gatherings were not just about protest; they were educational forums where attendees learned about policy issues and actionable steps to influence change.

Town halls, on the other hand, provided a more intimate setting for dialogue and engagement. Organizers would invite elected officials or candidates to address concerns directly, often using social media to promote the event and crowdsource questions. This two-pronged approach—public rallies for visibility and town halls for substance—ensured the movement remained both dynamic and grounded in local priorities. For those looking to replicate this model, start by identifying a core issue that resonates locally, then use social media to build momentum before planning a physical event.

Finally, the role of social media cannot be overstated. Platforms like Twitter and Facebook allowed organizers to bypass traditional media gatekeepers, reaching audiences directly with unfiltered messages. Hashtags like #TCOT (Top Conservatives on Twitter) became virtual meeting points for activists, while YouTube videos of rallies and town halls extended their reach far beyond physical attendees. To maximize impact, organizers should focus on creating shareable content—short, compelling clips or infographics that distill complex issues into digestible formats. This blend of offline and online tactics ensured the Tea Party’s message was both local and national, personal and political.

Understanding Political Machines: Power, Influence, and Their Role in Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$66.95

Ron Paul Supporters: His 2008 campaign energized a base focused on constitutional governance and economic freedom

Ron Paul's 2008 presidential campaign was a catalyst for a grassroots movement that would later become a significant part of the Tea Party's foundation. His message resonated with a diverse group of Americans, but it was the youth who became his most vocal and energetic supporters. College students and young professionals, often first-time voters, were drawn to Paul's unwavering commitment to individual liberty and his anti-establishment stance. This demographic, typically apathetic towards politics, found a cause to rally behind, and their enthusiasm became a defining feature of the campaign.

The campaign's focus on constitutional principles and economic liberty struck a chord with those disillusioned by the growing federal deficit and what they perceived as government overreach. Paul's supporters advocated for a return to the country's founding ideals, emphasizing limited government, personal responsibility, and free-market economics. This ideology, often referred to as libertarian-conservatism, became a rallying cry for a new political movement. The campaign's success in engaging these voters was evident in the record-breaking fundraising efforts, much of which came from small, individual donations, a testament to the passion and dedication of this emerging base.

A key strategy in mobilizing this support was the effective use of online platforms and social media, a novel approach at the time. Ron Paul's campaign harnessed the power of the internet to spread its message, creating a viral movement. Supporters organized through online forums, blogs, and social media groups, sharing campaign materials and coordinating local events. This digital activism not only raised awareness but also fostered a sense of community among geographically dispersed followers, uniting them under a common cause. The campaign's ability to engage and organize this tech-savvy demographic was a significant factor in its impact on the political landscape.

The legacy of Ron Paul's 2008 campaign is evident in the subsequent rise of the Tea Party movement, which adopted many of its core principles. The campaign's success in energizing a base passionate about constitutional governance and economic freedom laid the groundwork for a broader political shift. This movement, characterized by its grassroots nature and focus on individual liberty, continues to influence American politics, shaping policy debates and electoral outcomes. Understanding this campaign's role provides valuable insights into the formation and evolution of modern conservative and libertarian political activism.

In practical terms, the Ron Paul campaign's strategy offers lessons in political mobilization, particularly in engaging young voters and utilizing digital tools. For political organizers, this case study highlights the importance of authentic messaging and the potential of online communities in building a dedicated supporter base. By tapping into the energy of these groups and providing a platform for their ideals, campaigns can create a lasting impact, as evidenced by the enduring influence of Ron Paul's 2008 run on the Tea Party movement and beyond. This approach, when combined with a clear and consistent message, can be a powerful tool for political change.

Understanding the Dominant Political Parties: Their Names and Influence

You may want to see also

Corporate Backing: Groups like FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity provided funding and organizational support

The Tea Party movement, often portrayed as a grassroots uprising, was significantly bolstered by corporate-backed organizations that provided the financial and logistical scaffolding necessary for its rapid ascent. Among these, FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) stand out as key architects, funneling millions of dollars into organizing rallies, training activists, and amplifying the movement’s message. Their involvement raises questions about the authenticity of the Tea Party’s "bottom-up" narrative, revealing a top-down structure that shaped its trajectory.

Consider the mechanics of this support: FreedomWorks, co-founded by former House Majority Leader Dick Armey, operated as a training ground for Tea Party activists, offering workshops on media strategy, lobbying, and campaign tactics. AFP, funded by the Koch brothers, focused on mobilizing local chapters and financing high-profile events, such as the 2009 Taxpayer March on Washington. These groups didn’t merely react to the movement; they proactively steered it, ensuring alignment with corporate-friendly policies like deregulation and tax cuts. For instance, AFP’s “No Climate Tax” pledge became a litmus test for candidates, illustrating how corporate priorities were embedded in the Tea Party’s agenda.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between the Tea Party’s populist rhetoric and its corporate underwriting. While activists rallied against government overreach, the organizations backing them were deeply intertwined with corporate interests. FreedomWorks, for example, received funding from corporations like Philip Morris and AT&T, while AFP’s Koch-funded campaigns targeted environmental regulations that threatened industries like oil and gas. This duality—a movement decrying elitism while being funded by elites—underscores the complexity of its origins and the strategic role of these groups in shaping its identity.

To understand the impact of this corporate backing, examine the outcomes: the Tea Party’s influence on the 2010 midterm elections, where it helped flip the House to Republican control, was no accident. AFP alone spent over $40 million on ads and grassroots efforts that cycle. This investment wasn’t altruistic; it was a calculated strategy to advance policies benefiting corporate donors. For activists, this should serve as a cautionary tale: while the movement’s energy was genuine, its direction was often dictated by forces outside the town hall meetings and protests.

In practical terms, this corporate influence offers a blueprint for dissecting modern political movements. Look beyond the slogans and ask: Who funds the organizers? What policies are being prioritized? For those involved in activism, transparency about funding sources is critical. For observers, recognizing the role of groups like FreedomWorks and AFP provides a clearer lens for understanding how seemingly organic movements can be shaped by external interests. The Tea Party’s story is a reminder that in politics, following the money often reveals the true power dynamics at play.

Why the US Political System Resists Third-Party Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The base of the Tea Party movement was primarily composed of grassroots conservatives, libertarians, and independent voters who were frustrated with government spending, taxation, and perceived overreach.

While the Tea Party movement attracted many Republican voters, it was not officially formed by the Republican Party. It emerged as a decentralized, grassroots movement with its own distinct identity.

No single individual or group is credited with starting the Tea Party movement. It gained momentum through local activists, conservative media personalities, and organizations like FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity.

The movement gained national attention after a series of protests in 2009, particularly in response to government bailouts and healthcare reform. However, it lacked a single founding event or leader, relying instead on widespread local activism.