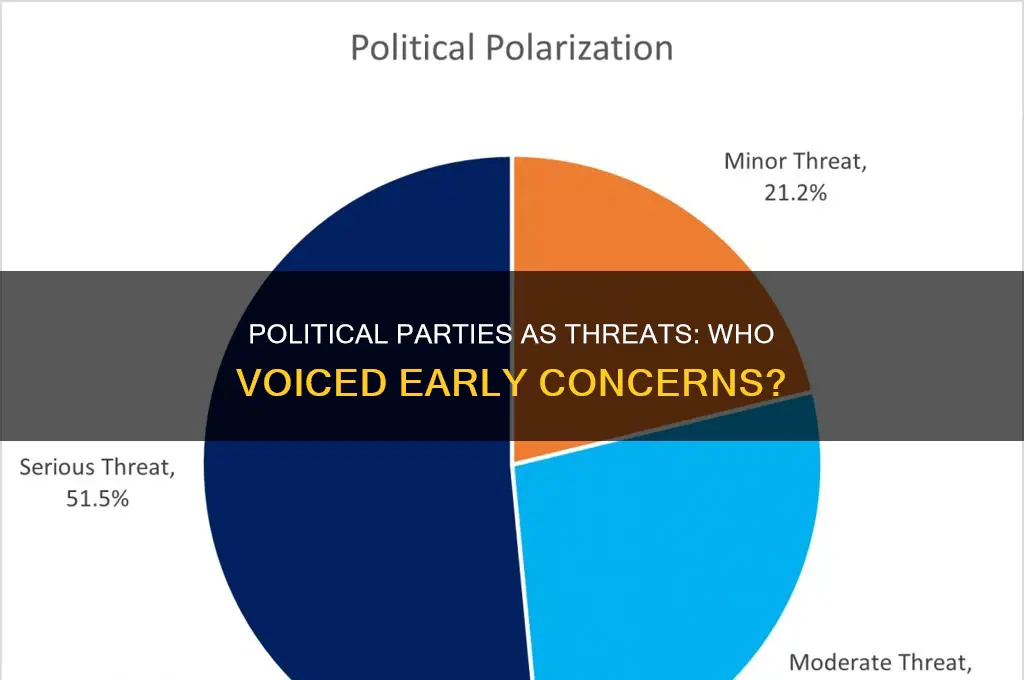

The concern that political parties posed a threat to the stability and integrity of governance dates back to the early days of American democracy, with none other than George Washington expressing this sentiment in his Farewell Address of 1796. Washington warned against the baneful effects of the spirit of party, arguing that political factions could undermine national unity, foster division, and prioritize partisan interests over the common good. His cautionary words highlighted the potential for parties to create conflicts, erode public trust, and distract from the principles of effective leadership. This concern has since resonated across various political systems, sparking ongoing debates about the role and impact of political parties in shaping societies and democracies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Papers Authors: Hamilton, Jay, and Madison warned about factions leading to instability in government

- John Adams: Early U.S. president feared parties would divide the nation and corrupt politics

- George Washington: First president cautioned against parties in his farewell address, calling them dangerous

- Thomas Jefferson: Despite leading a party, he later expressed regret over partisan conflicts

- Anti-Federalists: Opposed strong parties, arguing they would undermine individual liberties and local control

Federalist Papers Authors: Hamilton, Jay, and Madison warned about factions leading to instability in government

The Federalist Papers, a collection of 85 essays penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym Publius, remain a cornerstone of American political thought. Among their most prescient warnings was the danger of factions—groups united by a common interest adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the whole. These authors, architects of the U.S. Constitution, foresaw how factions could destabilize government by prioritizing narrow agendas over the common good. Their concern was not merely theoretical; it was a practical alarm rooted in the fragile experiment of American democracy.

Consider the analytical lens: Hamilton, Madison, and Jay argued that factions naturally arise in free societies due to the unequal distribution of property, differing opinions, and conflicting passions. In Federalist No. 10, Madison famously declared that factions are "sown in the nature of man" and impossible to eliminate. Instead, the Constitution aimed to control their effects by structuring government in a way that would mitigate their influence. This involved a system of checks and balances, a large republic where diverse interests would counteract one another, and a representative democracy that filtered the people’s will through elected officials. The goal was not to suppress factions but to prevent any single group from dominating and undermining the stability of the nation.

From an instructive perspective, the authors offered a roadmap for managing factionalism. They emphasized the importance of a well-designed government that could withstand the pressures of competing interests. For instance, they advocated for a bicameral legislature—the House of Representatives reflecting the passions of the people and the Senate providing a more deliberative, stabilizing force. This dual structure was intended to slow down decision-making, ensuring that laws were made with careful consideration rather than impulsive factional demands. Modern policymakers could take a page from this playbook by prioritizing institutional design over short-term political gains, fostering a government resilient to the whims of factions.

A persuasive argument emerges when we compare the Federalist Papers’ warnings to contemporary political landscapes. Today, polarization and partisan gridlock often paralyze governments, echoing the instability Hamilton, Jay, and Madison feared. The rise of single-issue advocacy groups, ideological echo chambers, and hyper-partisan media has amplified factional voices, sometimes at the expense of compromise and governance. By revisiting the Federalist Papers, we are reminded that the health of a democracy depends on its ability to balance competing interests, not allow them to dominate. This is not a call to eliminate political parties but to recognize their potential to fracture unity and act accordingly.

Finally, a descriptive approach highlights the enduring relevance of the authors’ concerns. Imagine a government where every decision is a battleground for factions, where the common good is perpetually hostage to special interests. This was the dystopia the Federalist Papers sought to prevent. Their solution—a republic designed to dilute the power of factions—remains a blueprint for stability. By studying their warnings, we gain not just historical insight but practical guidance for navigating the complexities of modern politics. The challenge lies in applying their principles to an era they could scarcely have imagined, yet their core message remains timeless: unchecked factions are a threat to governance, and vigilance is required to preserve the union.

Must Candidates Accept Party Funding? Exploring Political Finance Rules

You may want to see also

John Adams: Early U.S. president feared parties would divide the nation and corrupt politics

John Adams, the second president of the United States, harbored a deep-seated fear that political parties would fracture the young nation and corrupt its political system. His concerns were rooted in the belief that parties would prioritize self-interest over the common good, fostering division rather than unity. Adams’s warnings, though issued in the late 18th century, resonate with modern political challenges, offering a timeless cautionary tale about the dangers of partisan polarization.

Adams’s skepticism of political parties was not merely theoretical; it was shaped by his experiences during the nation’s formative years. He witnessed the emergence of factions within the Continental Congress and the early federal government, which he believed undermined rational debate and sound governance. In a letter to Jonathan Jackson in 1787, Adams wrote, “There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other.” This prescient observation highlights his fear that parties would create an adversarial system, where compromise and collaboration would be sacrificed for ideological purity and power.

To understand Adams’s perspective, consider his view of human nature. He believed that parties would exploit the weaknesses of individuals, amplifying ambition and greed rather than fostering virtue and public service. In his eyes, politicians aligned with a party would be more likely to act in their own interest or that of their faction, rather than for the benefit of the nation. This corruption, he argued, would erode trust in government and destabilize the republic. Adams’s solution was not to eliminate political differences but to encourage leaders to rise above party loyalties and act with integrity.

A practical takeaway from Adams’s concerns is the importance of fostering non-partisan spaces in modern politics. For instance, citizens can advocate for reforms like ranked-choice voting or open primaries, which reduce the dominance of two-party systems and encourage candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. Additionally, individuals can engage in cross-party dialogues, focusing on shared values rather than ideological differences. By doing so, they can help mitigate the divisive effects of partisanship and honor Adams’s vision of a unified nation.

In retrospect, Adams’s fears were not unfounded. The rise of extreme partisanship in contemporary politics has led to gridlock, polarization, and a decline in public trust. His warnings serve as a reminder that the health of a democracy depends on leaders and citizens prioritizing the common good over party loyalty. While political parties are an inevitable feature of modern governance, Adams’s insights challenge us to strive for a system where cooperation and integrity prevail over division and corruption.

The Pro-Slavery Stance: Uncovering 1790s Political Party Allegiances

You may want to see also

George Washington: First president cautioned against parties in his farewell address, calling them dangerous

In his 1796 Farewell Address, George Washington issued a prescriptive warning against the dangers of political parties, a stance rooted in his experience leading a fragile, newly independent nation. He argued that parties fostered "the alternate domination of one faction over another," threatening the stability of the republic. Washington’s caution was not abstract; it was born from observing the bitter divisions between Federalists and Anti-Federalists during his presidency. He believed parties prioritized self-interest over the common good, creating an environment where compromise became impossible and unity eroded. This warning remains a foundational text in American political thought, offering a timeless critique of partisanship.

Washington’s analysis of party behavior was strikingly instructive. He identified how parties could manipulate public opinion, exploit regional differences, and undermine the Constitution. For instance, he warned that parties might "enfeeble the public administration" by obstructing legislation for political gain. His solution was not to outlaw parties but to cultivate a citizenry capable of resisting their divisive tactics. Washington urged Americans to prioritize national identity over party loyalty, a call to action that remains relevant in an era of polarized politics. His address serves as a step-by-step guide to safeguarding democracy from internal fragmentation.

A comparative lens reveals the enduring relevance of Washington’s concerns. Modern political parties often mirror the dangers he described, with hyper-partisanship leading to legislative gridlock and eroded trust in institutions. For example, the 2020s have seen parties weaponize issues like healthcare and climate change, prioritizing electoral victory over policy solutions. Washington’s warning acts as a cautionary tale, reminding us that unchecked partisanship can destabilize even the strongest democracies. His emphasis on unity and compromise offers a stark contrast to today’s winner-takes-all political culture.

Practically, Washington’s Farewell Address provides actionable takeaways for contemporary citizens. First, engage in informed, non-partisan discourse to counter the echo chambers of modern media. Second, support candidates who prioritize national interests over party agendas. Third, advocate for structural reforms, such as ranked-choice voting, to reduce the dominance of two-party systems. By heeding Washington’s advice, individuals can mitigate the dangers of partisanship and strengthen democratic resilience. His words are not just historical artifacts but a roadmap for navigating today’s political challenges.

Christopher Columbus' Political Allegiances: Monarchist, Expansionist, or Opportunist?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Thomas Jefferson: Despite leading a party, he later expressed regret over partisan conflicts

Thomas Jefferson, one of the United States' founding fathers and the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, played a pivotal role in shaping the nation's early political landscape. As the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, he championed states' rights, limited government, and agrarian ideals. Yet, despite his instrumental role in party politics, Jefferson later expressed profound regret over the partisan conflicts that emerged during his presidency and beyond. This paradox—a party leader lamenting the very system he helped create—offers a nuanced lesson in the unintended consequences of political division.

Consider the context of Jefferson's era. The early 1800s saw the rise of America's first party system, pitting Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans against Alexander Hamilton's Federalists. While Jefferson initially viewed parties as temporary alliances to defend principles, he soon witnessed their transformation into entrenched factions. In his 1823 letter to John Taylor, Jefferson lamented, "Men by separating themselves into parties... and acting solely with a view to their own, give to selfish passions free play, and thus become the instruments of the wicked." This shift from principled debate to self-serving partisanship marked the beginning of his disillusionment.

Jefferson's regret was not merely philosophical but deeply personal. His presidency, from 1801 to 1809, was marred by bitter partisan strife, including the contentious election of 1800, which required a House of Representatives tiebreaker. Even his own vice president, Aaron Burr, became embroiled in scandal and was tried for treason. These experiences led Jefferson to conclude that parties, rather than fostering unity, exacerbated division. In a letter to Edward Livingston in 1825, he wrote, "The evil of parties in our country is becoming extreme, and their baneful effects will soon destroy all confidence between them."

To understand Jefferson's evolution, contrast his early optimism with his later pessimism. In 1789, he wrote to James Madison, "I have little fear that the circumstances which led to the division between Federalists and Anti-Federalists will again occur to break the Union into new fragments." Yet, by 1821, he confessed to William Ludlow, "I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man." This shift underscores the corrosive impact of partisan politics on his idealistic vision of a unified republic.

For modern readers, Jefferson's story serves as a cautionary tale. While political parties can mobilize support and structure governance, they risk devolving into tribalism if unchecked. Practical steps to mitigate this include fostering cross-party collaboration, prioritizing issues over ideology, and encouraging voters to engage with diverse perspectives. Jefferson's regret reminds us that even well-intentioned systems can sow discord, and it is our responsibility to steer them toward constructive dialogue rather than destructive division.

Bridging the Divide: Strategies to Engage Opposite Political Perspectives

You may want to see also

Anti-Federalists: Opposed strong parties, arguing they would undermine individual liberties and local control

The Anti-Federalists, a diverse coalition of early American political thinkers, stood firmly against the emergence of strong political parties, fearing they would erode the very foundations of a free society. Their concerns were rooted in a deep-seated belief that centralized power, whether in the hands of a monarch or a dominant political faction, posed an existential threat to individual liberties and local autonomy. This perspective, though often overshadowed by the Federalists' vision of a strong central government, offers a critical lens through which to examine the dangers of partisan politics.

Consider the Anti-Federalist argument as a cautionary tale, a historical precedent for modern political discourse. They believed that powerful parties would inevitably prioritize their own survival and expansion over the welfare of the people. In their view, this would lead to a concentration of authority, stifling the diverse voices and interests of local communities. For instance, they argued that a dominant party could manipulate public opinion, control legislative agendas, and appoint loyalists to key positions, thereby creating a self-perpetuating oligarchy. This scenario, they warned, would leave individual citizens with little say in governance, effectively reducing their role to that of passive spectators.

The Anti-Federalists' stance was not merely theoretical; it was a practical response to the political climate of their time. They witnessed the rise of factions during the Constitutional ratification debates and feared these divisions would deepen, leading to a system where party loyalty superseded the common good. To prevent this, they advocated for a more decentralized approach, emphasizing the importance of state and local governments as bulwarks against centralized power. This perspective encourages us to reflect on the balance between national unity and regional diversity, a tension that remains relevant in contemporary political discussions.

In today's political landscape, where party polarization often dominates headlines, the Anti-Federalist warning takes on new urgency. Their argument suggests that when parties become too powerful, they can distort the democratic process, making it less about representing the people's will and more about advancing partisan agendas. This can result in policies that favor specific interest groups over the general populace, further marginalizing those who do not align with the dominant party's ideology. To counter this, one might consider promoting local initiatives and community-driven decision-making processes, ensuring that power remains distributed and accessible to all citizens.

The Anti-Federalists' opposition to strong parties serves as a reminder that the health of a democracy depends on constant vigilance against the concentration of power. By advocating for individual liberties and local control, they offered a vision of governance that prioritizes the people's direct involvement in shaping their political destiny. This perspective is not just a historical footnote but a living principle, challenging us to critically assess the role of political parties and their impact on the freedoms we hold dear. It invites a reevaluation of our political systems, encouraging a more inclusive and participatory approach to governance.

Unveiling the Origins of Political Party Funding: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Washington expressed this concern in his Farewell Address in 1796.

Washington warned that political parties could lead to "the alternate domination of one faction over another," undermine national unity, and serve selfish interests rather than the common good.

Washington believed they could foster division, encourage corruption, and distract from the principles of good governance and the welfare of the nation.

Yes, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison initially shared similar concerns, though they later became leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Despite his warning, political parties quickly emerged and became a central feature of American politics, shaping the two-party system that persists today.

![[ { THE FEDERALIST PAPERS } ] by Madison, James (AUTHOR) Nov-03-1987 [ Paperback ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51zoLehRStL._AC_UY218_.jpg)