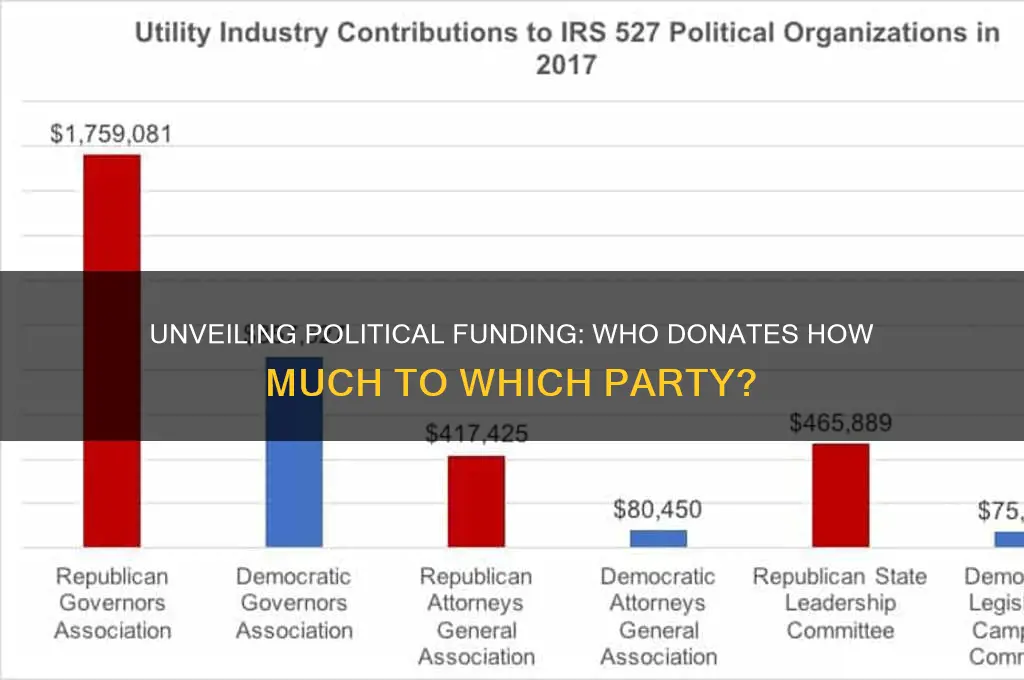

The question of who contributes how much money to political parties is a critical aspect of understanding modern political landscapes. Financial contributions play a pivotal role in shaping campaigns, influencing policies, and determining the reach and impact of political parties. These contributions often come from a diverse array of sources, including individual donors, corporations, labor unions, and special interest groups, each with their own motivations and expectations. Transparency in political funding is essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring democratic integrity, yet the complexity of campaign finance laws and the rise of undisclosed dark money have made it increasingly challenging to track and regulate these contributions effectively. As such, examining the flow of money into political parties reveals not only the financial underpinnings of political power but also the broader dynamics of influence and accountability in democratic systems.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Corporate donations and their influence on political party funding

- Individual contributions from wealthy donors to political campaigns

- Role of PACs (Political Action Committees) in party financing

- Government funding and public financing of political parties

- Small-dollar donations and grassroots fundraising for political campaigns

Corporate donations and their influence on political party funding

Corporate donations to political parties are a double-edged sword, offering financial lifelines while raising ethical concerns. In the United States, for instance, corporations contributed over $4 billion to federal elections between 2010 and 2020, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. This influx of funds allows parties to run competitive campaigns, but it also creates a dependency that can skew policy priorities. When a corporation donates millions, it often expects a return on investment, whether through favorable legislation, regulatory leniency, or access to decision-makers. This quid pro quo dynamic undermines the principle of equal representation, as corporate interests may overshadow those of ordinary citizens.

Consider the pharmaceutical industry, which has consistently ranked among the top corporate donors in the U.S. In 2020 alone, pharmaceutical companies and their trade associations contributed over $170 million to political campaigns and lobbying efforts. Coincidentally, policies favoring drug price protections and patent extensions have been enacted, benefiting these corporations at the expense of consumers. This example illustrates how corporate donations can distort the political process, prioritizing profit over public welfare. Critics argue that such influence perpetuates systemic inequalities, as corporations wield disproportionate power in shaping laws that affect millions.

To mitigate the influence of corporate donations, some countries have implemented strict regulations. In Canada, for example, corporate and union donations to federal political parties are banned, with individual contributions capped at $1,650 annually. This model shifts the funding burden to grassroots supporters, fostering a more democratic system. However, even in regulated environments, corporations find ways to exert influence, such as through political action committees (PACs) or indirect funding mechanisms. This highlights the need for continuous vigilance and reform to ensure transparency and accountability in political financing.

For those concerned about corporate influence, practical steps can be taken to counteract this trend. First, support candidates who refuse corporate donations and rely on small-dollar contributions from individuals. Second, advocate for campaign finance reforms that limit or disclose corporate contributions. Third, engage in shareholder activism by pressuring corporations to adopt ethical donation policies. While these actions may seem small, collective efforts can create a ripple effect, challenging the status quo and reclaiming the political process for the people. The ultimate takeaway is clear: corporate donations are not inherently evil, but their unchecked influence threatens the integrity of democratic institutions.

Who Controls Baltimore? Exploring the Dominant Political Party in the City

You may want to see also

Individual contributions from wealthy donors to political campaigns

Wealthy individuals have long played a disproportionate role in funding political campaigns, often leveraging their financial clout to influence policy and gain access to decision-makers. In the United States, for instance, the top 1% of donors accounted for nearly 40% of all federal campaign contributions in the 2020 election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. This concentration of funding raises questions about the equity of political representation, as candidates may prioritize the interests of their wealthiest backers over those of the broader electorate.

Consider the mechanics of these contributions: high-net-worth individuals often donate directly to campaigns, political action committees (PACs), or super PACs, which can accept unlimited funds. For example, in the 2020 U.S. presidential race, billionaire Michael Bloomberg spent over $1 billion on his own campaign, while others like Tom Steyer contributed tens of millions to super PACs supporting specific candidates. These large sums can dwarf small-dollar donations, creating an imbalance in campaign resources. To mitigate this, some countries impose strict caps on individual donations—Canada, for instance, limits individual contributions to CAD $1,650 annually per party—but such regulations are often absent or contested in the U.S. due to free speech arguments.

The impact of wealthy donors extends beyond elections, shaping policy agendas and legislative outcomes. Studies show that politicians are more likely to meet with high-dollar contributors and consider their policy preferences. For instance, a 2018 study by researchers at Princeton and Northwestern universities found that U.S. senators were significantly more responsive to the policy priorities of the wealthy than those of middle- or lower-income constituents. This dynamic can skew policies toward tax cuts for the rich, deregulation, or other measures favoring elite interests, potentially undermining democratic ideals of equal representation.

To navigate this landscape, voters and advocates must scrutinize campaign finance data, which is publicly available in many democracies. Tools like the U.S. Federal Election Commission’s database or OpenSecrets.org allow citizens to track donor contributions and identify patterns of influence. Additionally, supporting candidates who rely on small-dollar donations or advocating for public financing of elections can help level the playing field. While wealthy donors will always seek to amplify their voices, transparency and systemic reforms can ensure their outsized contributions do not distort the democratic process.

Rosie Tarot Politics: Unveiling the Mystic's Influence on Modern Governance

You may want to see also

Role of PACs (Political Action Committees) in party financing

Political Action Committees (PACs) are pivotal in party financing, serving as conduits for funneling money into political campaigns while operating within legal contribution limits. Unlike individual donors, who are capped at $3,300 per candidate per election, PACs can contribute up to $5,000 per candidate per election and $15,000 annually to national party committees. This structural advantage allows PACs to amplify their influence, often aggregating contributions from like-minded individuals, corporations, or unions to support specific candidates or causes. For instance, the National Association of Realtors’ PAC consistently ranks among the top contributors, strategically backing candidates who align with their policy interests.

Analyzing the role of PACs reveals their dual nature: they democratize political participation by pooling resources from smaller donors, yet they also risk skewing representation toward well-funded interests. A 2022 study by OpenSecrets found that 15% of all federal campaign contributions came from PACs, with corporate PACs outspending labor PACs by a 3:1 ratio. This imbalance underscores how PACs can inadvertently prioritize the agendas of wealthy entities over grassroots concerns. Critics argue that this dynamic perpetuates a pay-to-play system, where access and influence are disproportionately awarded to those with deep pockets.

To navigate the PAC landscape effectively, consider these practical steps: first, research a PAC’s funding sources and recipient candidates to ensure alignment with your values. Second, diversify your political engagement by supporting both PACs and individual candidates directly. Third, advocate for transparency reforms, such as requiring real-time disclosure of PAC contributions, to mitigate potential corruption. For example, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, also known as McCain-Feingold, attempted to curb PAC influence by banning soft money contributions, though loopholes like Super PACs have since emerged.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between traditional PACs and Super PACs, which emerged post-*Citizens United* (2010). While traditional PACs face contribution limits and must disclose donors, Super PACs can accept unlimited funds from corporations, unions, and individuals but cannot coordinate directly with candidates. This distinction illustrates how the evolution of PACs has reshaped party financing, with Super PACs now accounting for over $1 billion in spending in the 2020 election cycle alone. Such trends emphasize the need for ongoing regulatory scrutiny to balance free speech with equitable representation.

In conclusion, PACs are indispensable yet contentious players in party financing, offering both opportunities for collective political engagement and risks of undue influence. By understanding their mechanics, advocating for transparency, and diversifying support, individuals can navigate this complex terrain more effectively. As PACs continue to evolve, so too must the public’s vigilance in ensuring that democracy remains responsive to all voices, not just the loudest or wealthiest.

Why Political Thought Shapes Societies and Defines Our Future

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Government funding and public financing of political parties

Government funding of political parties is a mechanism designed to reduce reliance on private donations, thereby mitigating the influence of wealthy individuals or corporations on political agendas. In countries like Germany and Sweden, public financing constitutes a significant portion of party income, often tied to electoral performance or membership numbers. For instance, Germany allocates funds based on a party’s vote share in the last federal election, with a cap of €83 million annually per party. This model ensures financial stability for parties while limiting the sway of private interests, fostering a more equitable political landscape.

Implementing public financing requires careful consideration of funding criteria and accountability measures. A common approach is to tie grants to a party’s electoral success, as seen in Canada’s per-vote subsidy system, which provides $2.50 per vote received. However, such systems must include transparency mechanisms to prevent misuse. For example, France mandates that parties submit detailed financial reports to an independent oversight body, with penalties for non-compliance. Without robust accountability, public financing risks becoming a blank check for parties, undermining its intended purpose.

Critics argue that government funding stifles competition by favoring established parties over newcomers. Smaller parties often struggle to meet eligibility thresholds, such as minimum vote shares or membership requirements, as seen in Spain’s system. To address this, some countries, like Norway, allocate a portion of funds to all registered parties, regardless of size, ensuring diversity in the political arena. Striking a balance between stability and inclusivity is crucial for a fair system.

Public financing is not a panacea; it must be paired with strict limits on private donations to be effective. For instance, Belgium caps individual contributions at €500 per year, while corporate donations are banned outright. Such regulations prevent private donors from circumventing the system. However, enforcement remains a challenge, as evidenced by scandals in countries like Japan, where loopholes in campaign finance laws allowed for illicit contributions. A comprehensive framework, combining public funding with stringent private donation limits, is essential for integrity.

Ultimately, government funding of political parties serves as a tool to democratize political financing, but its success hinges on design and execution. Policymakers must weigh factors like funding criteria, accountability, inclusivity, and complementary regulations to create a system that enhances fairness without unintended consequences. When implemented thoughtfully, public financing can reduce corruption, level the playing field, and restore public trust in democratic institutions.

George Washington's Stance Against Political Parties: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Small-dollar donations and grassroots fundraising for political campaigns

Small-dollar donations, typically defined as contributions under $200, have emerged as a powerful force in modern political campaigns. These modest sums, when aggregated, can rival the impact of large donations from wealthy individuals or corporations. For instance, during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Bernie Sanders raised over $100 million from small-dollar donors, demonstrating the potential of grassroots fundraising. This approach not only democratizes campaign financing but also fosters a sense of ownership among a diverse base of supporters. By relying on small contributions, candidates can reduce their dependence on big-money interests, aligning their campaigns more closely with the values of everyday voters.

To harness the power of small-dollar donations, campaigns must adopt strategic grassroots fundraising techniques. A key step is building a robust digital infrastructure, including user-friendly donation platforms and engaging social media campaigns. Email lists and text messaging can be particularly effective for reaching donors directly. For example, ActBlue, a nonprofit fundraising platform, processed over $1.6 billion in small donations during the 2020 election cycle, showcasing the scalability of such tools. Campaigns should also focus on storytelling, highlighting how even $5 or $10 contributions can collectively make a significant impact. Transparency about how funds are used further builds trust and encourages repeat donations.

However, grassroots fundraising is not without challenges. Campaigns must invest time and resources into cultivating relationships with donors, which can be labor-intensive. Additionally, small-dollar donations often require a larger volume of contributors to match the financial impact of a single large donation. This means campaigns must consistently engage their base through personalized communication and regular updates. A cautionary note: over-reliance on digital fundraising can exclude older or less tech-savvy donors, so diversifying outreach methods is essential. For instance, combining online appeals with local events or phone banking can broaden participation.

The success of small-dollar fundraising lies in its ability to create a movement rather than just a campaign. Donors become more than financial contributors; they become advocates, volunteers, and ambassadors for the cause. Practical tips for maximizing this potential include setting achievable donation goals (e.g., "$5 Fridays") and offering incentives like campaign merchandise for recurring donors. Campaigns should also leverage data analytics to identify trends in donor behavior and tailor their appeals accordingly. For example, analyzing donation spikes after specific events or messages can inform future strategies.

In conclusion, small-dollar donations and grassroots fundraising represent a transformative approach to political campaign financing. By empowering everyday citizens to contribute, campaigns can build a sustainable and inclusive financial base. While challenges exist, the benefits—from reduced reliance on big money to increased voter engagement—make this strategy invaluable. As political landscapes evolve, the ability to mobilize grassroots support will remain a cornerstone of successful campaigns, proving that even the smallest contributions can drive significant change.

Political Marketing Strategies: How Campaigns Shape Public Opinion and Votes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary contributors include individuals (wealthy donors, party members), corporations, labor unions, Political Action Committees (PACs), and Super PACs, depending on the country's campaign finance laws.

Corporate contributions vary widely but can range from thousands to millions of dollars annually, often directed through PACs or direct donations where legally permitted.

Yes, small individual donors collectively contribute a substantial amount, especially in grassroots campaigns, though their average donations are smaller compared to large donors.

Super PACs can raise and spend unlimited amounts of money from corporations, unions, and individuals to support or oppose candidates, but they cannot coordinate directly with political parties.

Transparency varies by country and region; some nations require detailed disclosure of donations, while others have looser regulations, making it harder to track contributions.