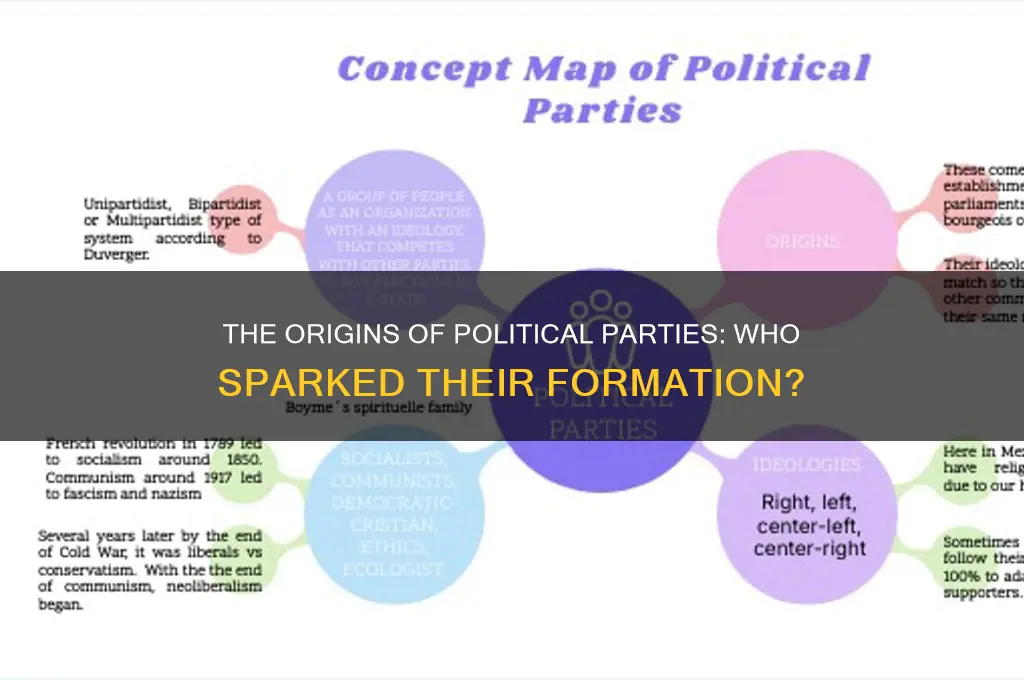

The formation of political parties can be traced back to the early days of democratic governance, where differing ideologies and interests among leaders and citizens led to the coalescing of like-minded groups. In the United States, for instance, the emergence of political parties in the late 18th century was largely driven by the contrasting visions of key Founding Fathers, such as Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, who disagreed on issues like the role of the federal government and economic policies. These divisions gave rise to the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, setting a precedent for organized political factions. Similarly, in other democracies, parties often formed as a result of societal cleavages, economic disparities, or cultural differences, with leaders and activists rallying supporters around shared goals and principles. Thus, the genesis of political parties is deeply rooted in the natural human tendency to organize and advocate for collective interests in the face of diverse and often competing priorities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | Political parties formed due to societal divisions, ideological differences, and the need for organized representation. |

| Key Figures | Early political parties were influenced by leaders like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison in the U.S. |

| Ideological Differences | Parties emerged from conflicting views on governance, economics, and individual rights (e.g., Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists). |

| Electoral Systems | The introduction of competitive elections and democratic processes encouraged the formation of parties to mobilize voters. |

| Social and Economic Factors | Parties often formed around class interests, regional identities, or responses to industrialization and urbanization. |

| Institutional Needs | The need for organized lobbying, legislative cohesion, and executive power consolidation drove party formation. |

| Global Influence | Political parties spread globally as nations adopted democratic systems, often modeled after early examples like the U.S. and U.K. |

| Technological Advances | Printing presses and mass media facilitated party communication and mobilization in the 18th and 19th centuries. |

| Legal Frameworks | Constitutional and legal structures (e.g., two-party systems, proportional representation) shaped party development. |

| Cultural Dynamics | Parties often reflected cultural values, religious beliefs, and ethnic identities within societies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Interests: Competing economic groups sought political power to influence policies favoring their financial goals

- Social Divisions: Cultural, religious, and regional differences fueled alliances among like-minded individuals

- Ideological Conflicts: Disagreements over governance, rights, and societal structure led to faction formation

- Leadership Ambitions: Influential figures organized followers to gain control and advance personal agendas

- Electoral Systems: Competitive elections incentivized coalition-building, formalizing groups into organized parties

Economic Interests: Competing economic groups sought political power to influence policies favoring their financial goals

The formation of political parties is often a direct response to the clash of economic interests within a society. Historically, competing economic groups—such as industrialists, farmers, merchants, and laborers—have sought political power to shape policies that align with their financial goals. For instance, in the early United States, the Federalist Party represented the interests of bankers and merchants, advocating for a strong central government and financial stability, while the Democratic-Republican Party championed the agrarian economy of small farmers. This division highlights how economic interests can drive the creation and alignment of political factions.

Consider the Industrial Revolution in 19th-century Europe, where the rise of factory owners and the working class led to the emergence of conservative and socialist parties. Industrialists sought policies that minimized labor costs and maximized profits, while workers demanded better wages, shorter hours, and safer conditions. These competing interests fueled the formation of political parties that acted as vehicles for economic advocacy. For example, the British Labour Party was founded to represent the interests of the working class, while the Conservative Party often aligned with industrial and business elites.

To understand this dynamic, examine the role of lobbying and campaign financing in modern democracies. Economic groups invest heavily in political parties to ensure their interests are prioritized. In the United States, corporations and unions spend billions on lobbying and campaign contributions to influence legislation on taxes, trade, and labor regulations. This financial influence often determines which policies are enacted, reinforcing the connection between economic interests and party formation. For instance, the pharmaceutical industry’s lobbying efforts have shaped drug pricing policies, while agricultural subsidies are heavily influenced by farming conglomerates.

A comparative analysis reveals that economic interests drive party formation across diverse political systems. In India, caste-based economic groups have historically aligned with political parties to secure resources and representation. Similarly, in post-apartheid South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) initially represented the economic aspirations of the black majority, while opposition parties often catered to business interests. These examples illustrate how economic divisions are a universal catalyst for political organization.

To address the influence of economic interests on party formation, transparency and regulation are essential. Implementing stricter campaign finance laws and requiring detailed disclosure of lobbying activities can reduce the disproportionate power of wealthy economic groups. Additionally, fostering inclusive economic policies that balance the interests of all stakeholders can mitigate the need for extreme partisan divisions. For instance, Nordic countries have successfully balanced capitalist growth with robust social welfare programs, reducing economic inequality and partisan polarization. By learning from such models, societies can ensure that political parties serve the broader public interest rather than narrow economic agendas.

Unveiling Political Parties' Key Roles: 6 Essential Functions Explained

You may want to see also

Social Divisions: Cultural, religious, and regional differences fueled alliances among like-minded individuals

Human societies have always been mosaics of diverse cultures, religions, and regional identities. These inherent differences, rather than being mere background noise, often act as catalysts for the formation of political alliances. Consider the United States in the early 19th century. The divide between agrarian Southern states and industrial Northern states wasn't just economic; it was deeply rooted in cultural attitudes towards labor, social hierarchy, and the role of government. This cultural chasm fueled the formation of distinct political factions, ultimately crystallizing into the Democratic and Republican parties as we know them today.

Similarly, religious differences have historically been a powerful force in shaping political landscapes. The English Civil War of the 17th century wasn't merely a power struggle between king and parliament; it was a conflict fueled by deep religious divisions between Protestants and Catholics. These religious affiliations translated into political alliances, with Puritans and other Protestant groups aligning with Parliament against the monarch's perceived Catholic sympathies.

The power of regional identity in forging political alliances is equally evident. In India, a nation with immense linguistic and cultural diversity, regional parties have consistently challenged the dominance of national parties. Parties like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu and the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in Andhra Pradesh draw their strength from a shared regional identity, advocating for the specific needs and aspirations of their respective states. This regional focus often leads to alliances with other regional parties, creating a counterweight to the centralized power of national parties.

It's crucial to recognize that these social divisions don't operate in isolation. They intersect and intertwine, creating complex webs of allegiance. For instance, in many African countries, ethnic and religious identities often overlap with regional affiliations, leading to political parties that represent a specific ethnic group within a particular region. Understanding these intersections is vital for comprehending the dynamics of political party formation and the often fractious nature of political landscapes.

While social divisions can fuel political polarization, they also present opportunities for coalition building and compromise. Recognizing and addressing the legitimate concerns of diverse groups is essential for fostering inclusive political systems. By acknowledging the role of cultural, religious, and regional differences in shaping political alliances, we can move beyond simplistic narratives of "us vs. them" and work towards building political systems that are truly representative of the complex tapestry of human society. This requires a nuanced understanding of these divisions, moving beyond mere tolerance to active engagement and dialogue.

Revitalizing Democracy: Strategies for Political Parties to Regain Relevance

You may want to see also

Ideological Conflicts: Disagreements over governance, rights, and societal structure led to faction formation

The roots of political parties often lie in ideological conflicts that fracture societies into distinct factions. Consider the early United States, where the Federalists and Anti-Federalists clashed over the ratification of the Constitution. Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, while Anti-Federalists, such as Patrick Henry, feared centralized power would erode states' rights. This disagreement over governance was not merely academic; it shaped the nation’s foundational policies and institutions. The Federalist Papers and Anti-Federalist writings exemplify how these ideological battles were fought not just in Congress but also in public discourse, laying the groundwork for organized political parties.

Ideological conflicts over rights have similarly spurred faction formation. The abolitionist movement in 19th-century Britain provides a compelling case. William Wilberforce and his allies pushed for the abolition of slavery, while pro-slavery interests, often tied to economic elites, resisted. This divide was not just about morality but also about economic structures and societal hierarchies. The formation of the Anti-Slavery Society and its opposition illustrate how disagreements over fundamental rights can crystallize into organized political movements. These factions did not merely debate; they mobilized public opinion, lobbied Parliament, and ultimately reshaped British society.

Societal structure itself often becomes a battleground for ideological conflicts, leading to the rise of political factions. The French Revolution’s split between the Jacobins and Girondins highlights this dynamic. The Jacobins, representing radical egalitarianism, sought to dismantle the aristocracy and redistribute wealth, while the Girondins, more moderate, favored a gradual approach. This conflict was not just about policy but about the very fabric of French society. The Reign of Terror and the Girondins’ eventual execution demonstrate how ideological disagreements over societal structure can escalate into violent factionalism. Such extremes underscore the stakes involved in these conflicts.

To understand how ideological conflicts lead to faction formation, consider the following steps: first, identify the core disagreement—governance, rights, or societal structure. Second, analyze how these disagreements are amplified through public discourse, media, and leadership. Third, observe how factions organize around these ideologies, often leveraging institutions like legislatures, courts, or grassroots movements. For instance, the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. saw factions like the NAACP and segregationist groups crystallize around opposing views on racial equality. Finally, recognize that these factions often evolve into formal political parties, as seen in the Democratic and Republican Parties’ realignment during the 1960s.

A cautionary note: ideological conflicts, while necessary for democratic discourse, can devolve into polarization if left unchecked. The key is to foster dialogue that bridges divides rather than deepens them. Practical tips include encouraging cross-party collaborations, promoting civic education, and supporting independent media. For example, countries like Germany have implemented proportional representation systems that incentivize coalition-building, reducing extreme factionalism. By understanding the mechanics of ideological conflicts, societies can navigate them constructively, ensuring that faction formation strengthens democracy rather than fracturing it.

Election Strategies: Unveiling Political Parties' Tactics to Win Votes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Leadership Ambitions: Influential figures organized followers to gain control and advance personal agendas

Throughout history, the formation of political parties has often been driven by the ambitions of influential leaders who sought to consolidate power and advance their personal agendas. These figures, armed with charisma, vision, or strategic acumen, organized followers into cohesive groups, laying the groundwork for structured political movements. One striking example is Alexander Hamilton’s role in the emergence of the Federalist Party in the United States. Hamilton, a staunch advocate for a strong central government, rallied supporters to counter the Democratic-Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson. His efforts were not merely ideological but deeply tied to his desire to shape the nation’s economic policies, such as the establishment of a national bank, which aligned with his personal vision of America’s future.

Consider the steps such leaders typically follow to achieve their goals. First, they identify a core set of principles or grievances that resonate with a significant portion of the population. Second, they leverage their influence to build a network of loyal followers, often through public speeches, written works, or strategic alliances. Third, they formalize this network into a structured organization, complete with leadership hierarchies and defined goals. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership in India’s independence movement illustrates this process. By mobilizing millions under the banner of nonviolent resistance, Gandhi not only challenged British colonial rule but also positioned himself as the central figure in the Indian National Congress, steering its agenda to align with his vision of a free and united India.

However, the pursuit of personal agendas by such leaders is not without risks. History is replete with examples where leadership ambitions led to internal divisions or authoritarian tendencies. In the case of Benito Mussolini, his rise to power through the National Fascist Party was fueled by his desire for absolute control and personal glory. While he successfully organized followers and seized power, his agenda ultimately led to Italy’s disastrous involvement in World War II and widespread suffering. This cautionary tale underscores the importance of balancing leadership ambition with accountability and the broader welfare of the populace.

To understand the impact of leadership ambitions on party formation, compare the approaches of Nelson Mandela and Robert Mugabe. Both were influential figures in their respective countries’ liberation movements, yet their leadership styles diverged sharply. Mandela, after organizing the African National Congress (ANC) to fight apartheid, prioritized reconciliation and democratic governance, ensuring the ANC remained a unifying force in post-apartheid South Africa. In contrast, Mugabe’s leadership of ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe was marked by increasing authoritarianism and a focus on personal power, leading to economic collapse and political instability. This comparison highlights how the same drive to organize followers can yield vastly different outcomes depending on the leader’s priorities.

In practical terms, recognizing the role of leadership ambitions in party formation offers valuable insights for both political strategists and citizens. For aspiring leaders, it emphasizes the need to align personal goals with the collective good, fostering trust and long-term sustainability. For citizens, it underscores the importance of critically evaluating leaders’ motives and holding them accountable. By understanding this dynamic, individuals can better navigate the complexities of political landscapes and contribute to the formation of parties that serve the broader interests of society, rather than the narrow ambitions of a few.

Exploring Greece's Political Landscape: A Guide to Its Major Parties

You may want to see also

Electoral Systems: Competitive elections incentivized coalition-building, formalizing groups into organized parties

The introduction of competitive electoral systems has been a pivotal force in the formation of political parties. In the early stages of democratic governance, elections were often unstructured, with candidates running as individuals rather than representatives of organized groups. However, as electoral systems evolved to prioritize competition, the need for coalition-building became apparent. This shift incentivized like-minded individuals to formalize their alliances, ultimately leading to the establishment of political parties. For instance, in the United Kingdom during the 18th century, the emergence of the Whig and Tory factions can be attributed to the increasing competitiveness of parliamentary elections, which encouraged the consolidation of interests and ideologies.

Consider the mechanics of an electoral system that fosters party formation. A key factor is the adoption of proportional representation or plurality voting systems, which reward the aggregation of votes. In proportional systems, parties are motivated to coalesce in order to secure a larger share of legislative seats, as seen in the Netherlands, where the fragmented party landscape is a direct consequence of its proportional electoral rules. Conversely, plurality systems, like the first-past-the-post model in the United States, encourage the formation of dominant parties that can effectively mobilize and consolidate voter support. Both systems, though different in structure, create an environment where coalition-building is not just beneficial but essential for electoral success.

To illustrate the process, examine the strategic decisions made by political actors in response to electoral incentives. In competitive elections, individuals or groups with shared goals must decide whether to remain independent or join forces. The calculus often favors unification, as it amplifies their collective voice and increases their chances of influencing policy. For example, in India’s diverse political landscape, regional parties frequently form pre-election coalitions to challenge national parties, demonstrating how electoral systems can directly shape party behavior. This strategic alignment is not merely a tactical choice but a structural response to the demands of the electoral framework.

A cautionary note is warranted, however. While competitive electoral systems drive party formation, they can also lead to unintended consequences, such as polarization or the marginalization of smaller groups. In systems where coalition-building is paramount, there is a risk that parties may prioritize internal cohesion over broader societal interests, potentially exacerbating divisions. For instance, in Israel’s highly proportional system, the proliferation of small parties has sometimes resulted in unstable governments and policy gridlock. Policymakers and reformers must therefore balance the benefits of party formation with mechanisms that ensure inclusivity and stability.

In conclusion, competitive electoral systems serve as a catalyst for the formation of political parties by creating incentives for coalition-building and formalizing groups into organized entities. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for anyone seeking to analyze or reform democratic institutions. By examining historical examples and structural factors, it becomes clear that the design of electoral systems is not just a technical detail but a fundamental determinant of political organization. Practical steps, such as evaluating the trade-offs between proportional and plurality systems, can help mitigate potential drawbacks while harnessing the benefits of party formation in fostering democratic governance.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Delaware: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties in the United States emerged primarily due to differing interpretations of the Constitution and governance among the Founding Fathers, notably between Alexander Hamilton (Federalists) and Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republicans).

In ancient Rome, political factions formed around influential families and leaders, such as the Optimates (aristocratic senators) and Populares (reformers like Julius Caesar and the Gracchi brothers), driven by power struggles and social reforms.

Modern political parties often arise from societal divisions over ideology, economics, or cultural issues, with key figures or movements catalyzing their formation, such as labor movements, nationalist leaders, or responses to industrialization.