The phrase capitalism political 1882 likely refers to the political and economic landscape of the late 19th century, a period marked by the rapid expansion of capitalism and industrialization. By 1882, capitalism had firmly established itself as the dominant economic system in many Western nations, reshaping societies, labor markets, and political ideologies. This era saw the rise of industrial magnates, the growth of urban centers, and the emergence of new political movements, such as socialism and labor unions, in response to the inequalities and exploitation often associated with unchecked capitalist practices. Politically, governments grappled with regulating industries, addressing worker rights, and balancing the interests of capital and labor, setting the stage for debates that would define the relationship between capitalism and politics for decades to come.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Capitalism's Rise in 1882: Global economic shifts and industrialization's impact on political systems during this pivotal year

- Political Parties and Capitalism: How political parties aligned with or opposed capitalist ideologies in 1882

- Labor Movements: Worker rights and socialist responses to capitalist exploitation in the late 19th century

- Imperialism and Capitalism: The role of capitalist economies in driving colonial expansion in 1882

- Government Policies: Legislative measures supporting or regulating capitalism in key nations during this period

Capitalism's Rise in 1882: Global economic shifts and industrialization's impact on political systems during this pivotal year

The year 1882 marked a pivotal moment in the rise of capitalism, as global economic shifts and industrialization began to reshape political systems worldwide. This period saw the consolidation of capitalist economies in Europe and North America, driven by advancements in technology, the expansion of international trade, and the exploitation of colonial resources. The industrial revolution had reached a stage where mass production, railways, and steamships were integrating markets, creating a global economy centered on capitalist principles. These changes not only transformed economic structures but also exerted profound influence on political ideologies and governance, as nations adapted to the demands of industrial capitalism.

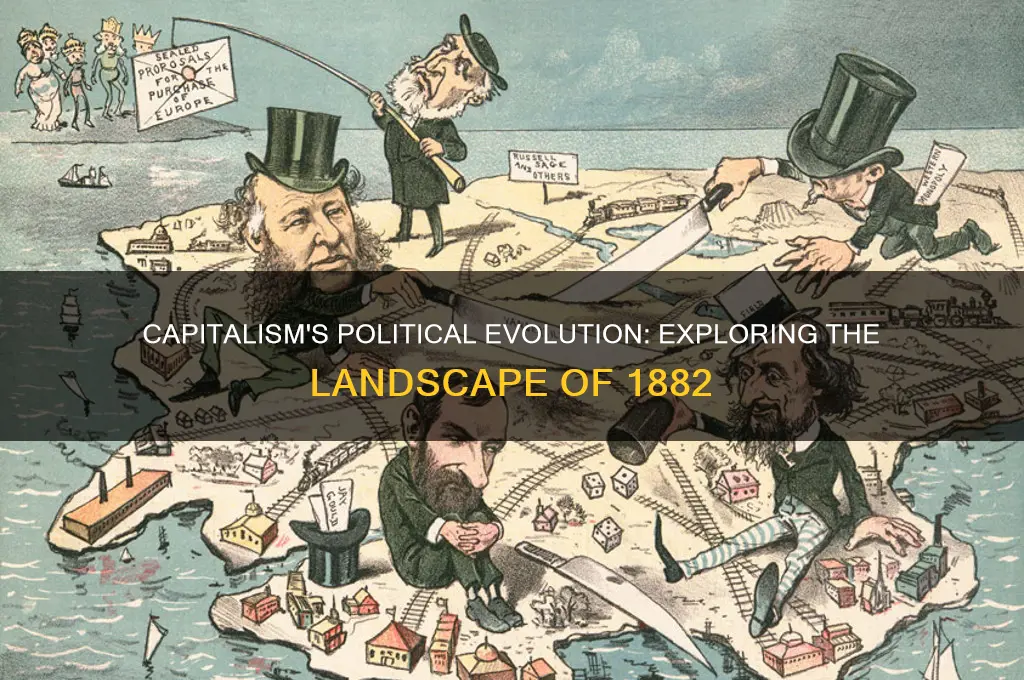

One of the most significant impacts of capitalism's rise in 1882 was the strengthening of nation-states as facilitators of economic growth. Governments began to play a more active role in fostering industrial development, often through policies that protected domestic industries, built infrastructure, and ensured access to raw materials from colonies. In countries like Germany and the United States, this era saw the emergence of a close relationship between industrialists and political elites, a phenomenon often referred to as "state monopoly capitalism." This alliance aimed to create stable conditions for capital accumulation, often at the expense of labor rights and social welfare, highlighting the political shifts necessitated by capitalist expansion.

The global economic shifts of 1882 also intensified imperialist competition among European powers, as capitalism's demand for markets and resources fueled colonial expansion. The "Scramble for Africa" accelerated during this period, with nations like Britain, France, and Germany racing to claim territories rich in raw materials. This imperialist drive was not merely economic but also political, as colonies became extensions of capitalist systems, governed by metropolitan powers to serve their industrial needs. The political systems of colonized regions were thus restructured to facilitate resource extraction and market integration, underscoring the global reach of capitalism's influence.

Industrialization and capitalism's rise in 1882 further exacerbated social inequalities, prompting political responses that would shape the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The growth of industrial cities led to the proliferation of a new working class, whose harsh living and working conditions sparked labor movements and socialist ideologies. In response, some political systems began to incorporate reforms aimed at mitigating social unrest, such as limited labor protections or welfare measures. However, these reforms were often insufficient, leading to the rise of more radical political movements that challenged the capitalist order. This tension between capitalism's benefits and its social costs became a defining feature of political systems during this era.

Finally, the rise of capitalism in 1882 contributed to the globalization of political and economic systems, as nations became increasingly interconnected through trade, finance, and technology. This interdependence fostered the development of international institutions and agreements, such as the emergence of the gold standard, which stabilized currency exchanges and facilitated global commerce. However, it also created vulnerabilities, as economic downturns in one region could quickly spread to others. The political systems of the time had to navigate this new globalized reality, balancing national interests with the demands of an integrated capitalist world. In this way, 1882 stands as a critical year in understanding how capitalism's ascent reshaped political landscapes on a global scale.

Understanding the Core Components of a Political Party Platform

You may want to see also

Political Parties and Capitalism: How political parties aligned with or opposed capitalist ideologies in 1882

In 1882, the political landscape across Europe and North America was deeply influenced by the rise of capitalism, with political parties either aligning with or opposing its ideologies. Capitalism, characterized by private ownership of the means of production, free markets, and the accumulation of capital, was a dominant economic force, but its political reception varied widely. In the United Kingdom, the Liberal Party was a key proponent of capitalist principles. Led by figures like William Ewart Gladstone, the Liberals advocated for free trade, limited government intervention in the economy, and the protection of individual property rights. These policies were seen as essential to fostering industrial growth and economic prosperity, aligning closely with capitalist ideals. The Liberals' support for capitalism was rooted in their belief in individual liberty and the benefits of a competitive market system.

In contrast, the Conservative Party in the UK, while not explicitly anti-capitalist, often favored policies that protected established industries and landowners. This stance sometimes led to tensions with the unfettered capitalism promoted by the Liberals. Conservatives supported tariffs and other protective measures to shield domestic industries from foreign competition, which was at odds with the free trade principles championed by capitalist ideologues. Their approach reflected a more cautious embrace of capitalism, prioritizing stability and the preservation of traditional economic structures over rapid industrialization.

On the European continent, socialist and labor movements were gaining momentum as a direct response to the excesses of capitalism. In Germany, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) emerged as a formidable force, advocating for the rights of workers and opposing the exploitation inherent in capitalist systems. Founded in 1875, the SPD by 1882 had solidified its position as a critic of capitalism, pushing for collective ownership of the means of production and greater economic equality. The party's opposition to capitalism was rooted in Marxist ideology, which viewed capitalism as inherently exploitative and unsustainable.

In the United States, the Republican Party was the primary political force aligned with capitalist interests in 1882. The Republicans, led by figures like President Chester A. Arthur, supported business growth, industrialization, and the expansion of markets. Their policies, including tariffs to protect American industries and subsidies for railroads, were designed to accelerate capitalist development. The Republican Party's alignment with capitalism was driven by its belief in the transformative power of industrial progress and the importance of private enterprise in achieving national prosperity.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party in the U.S. presented a more mixed stance on capitalism. While not explicitly anti-capitalist, many Democrats, particularly in the South and West, were critical of the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of industrialists and financiers. They advocated for policies that would benefit small farmers, laborers, and local businesses, often opposing the monopolistic practices of large corporations. This position reflected a populist skepticism of unchecked capitalism, though it did not amount to a full-scale rejection of the system.

In summary, 1882 was a year in which political parties across the Western world were deeply engaged with the question of capitalism. While some, like the UK Liberals and the U.S. Republicans, embraced capitalist principles as the key to economic progress, others, such as the German SPD, vehemently opposed it as exploitative. Parties like the UK Conservatives and the U.S. Democrats occupied a middle ground, supporting capitalism in principle but often advocating for measures to mitigate its negative effects. This diversity of perspectives highlights the complex and contested nature of capitalism as a political and economic ideology in the late 19th century.

Political Parties: Bridging Citizens and Government in Democratic Systems

You may want to see also

Labor Movements: Worker rights and socialist responses to capitalist exploitation in the late 19th century

In the late 19th century, the rapid industrialization and expansion of capitalism led to widespread exploitation of the working class. Long working hours, hazardous conditions, and meager wages characterized the lives of laborers, particularly in Europe and North America. This systemic exploitation gave rise to labor movements, which sought to secure basic worker rights and challenge the unchecked power of capitalist elites. The year 1882, in particular, marked a significant period of organizing and resistance, as workers began to collectively demand fair treatment and dignity in the workplace. These movements were not merely about improving wages or hours but were fundamentally about reclaiming humanity in the face of dehumanizing economic systems.

Socialist ideologies played a pivotal role in shaping the labor movements of this era. Thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had already laid the groundwork for understanding capitalism as an inherently exploitative system, where the proletariat (working class) was systematically oppressed by the bourgeoisie (capitalist class). By the 1880s, socialist parties and organizations were translating these ideas into actionable strategies for workers. They advocated for collective bargaining, the right to strike, and the establishment of labor unions as essential tools to counter capitalist exploitation. Socialist responses emphasized not just immediate reforms but also the long-term goal of restructuring society to prioritize communal well-being over profit.

One of the most significant developments in labor movements during this period was the formation and growth of trade unions. These organizations provided workers with a platform to negotiate with employers and demand better conditions. The year 1882 saw the continued rise of influential unions such as the Knights of Labor in the United States, which fought for the eight-hour workday and opposed child labor. Similarly, in Europe, unions like the British Trades Union Congress gained momentum, organizing strikes and protests to secure workers' rights. These unions often collaborated across borders, recognizing that capitalist exploitation was a global issue requiring international solidarity.

Labor movements also intersected with political activism, as workers sought legislative changes to protect their rights. Socialist and social democratic parties emerged as political vehicles for these demands, pushing for laws that regulated working hours, ensured workplace safety, and provided social security. For instance, the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) became a powerful force in advocating for workers' rights, even in the face of government repression. The late 19th century thus witnessed a growing recognition that political action was essential to complement industrial organizing, as workers realized that capitalism's exploitation could not be fully addressed without systemic change.

Despite facing severe opposition from governments and capitalists, labor movements achieved notable victories by the end of the 19th century. The legalization of unions, the reduction of working hours, and the introduction of labor protections were direct outcomes of workers' collective struggles. However, these gains were uneven and often limited, as capitalism continued to prioritize profit over people. Socialist responses to this reality remained critical, arguing that true liberation required a fundamental transformation of economic systems. The legacy of these movements laid the foundation for modern labor rights and continues to inspire contemporary struggles against exploitation.

Rise Against's Political Voice: Unraveling Their Activism and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Imperialism and Capitalism: The role of capitalist economies in driving colonial expansion in 1882

In 1882, the interplay between imperialism and capitalism was a defining feature of global politics and economics. Capitalist economies, particularly those of European powers like Britain, France, and Germany, played a pivotal role in driving colonial expansion. The capitalist system, with its inherent need for continuous growth and profit, fueled the scramble for colonies by seeking new markets, raw materials, and investment opportunities. This period, often referred to as the "Age of Imperialism," saw capitalist nations leveraging their economic might to establish dominance over less industrialized regions in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The logic was straightforward: colonies provided resources and markets essential for sustaining the capitalist engine, while the wealth extracted from these territories further enriched the imperial powers.

The industrial revolution had transformed capitalist economies by 1882, creating a surplus of manufactured goods that required global markets for consumption. Colonies became outlets for these products, ensuring that capitalist enterprises remained profitable. For instance, British textile industries relied heavily on exporting goods to India, a colony where local industries were systematically undermined to favor British imports. This economic exploitation was underpinned by political and military control, as capitalist nations used their power to enforce trade agreements and suppress resistance. The role of capitalism in this context was not merely economic but also ideological, as it justified colonial expansion as a civilizing mission to bring progress and modernity to "backward" regions.

Capitalist financiers and corporations were key actors in this imperialist endeavor. Banks and investment firms provided the capital necessary for colonial ventures, while companies like the British East India Company and the Dutch East Indies Company operated as quasi-state entities, often leading the charge in territorial expansion. The quest for raw materials, such as rubber, cotton, and minerals, further drove capitalist interests into uncharted territories. For example, King Leopold II of Belgium’s exploitation of the Congo for rubber and ivory exemplifies how individual capitalist ambitions aligned with state-sponsored imperialism, resulting in brutal colonization and economic extraction.

The political structures of capitalist nations were also deeply intertwined with imperialist goals. Governments enacted policies and laws that facilitated colonial expansion, often at the behest of powerful industrialists and financiers. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, which formalized the partition of Africa, is a prime example of how capitalist nations collaborated to divide territories and secure their economic interests. By 1882, the political elites of these nations were increasingly influenced by the capitalist class, whose wealth and power depended on the continued expansion of imperial territories.

In conclusion, the role of capitalist economies in driving colonial expansion in 1882 was both systemic and deliberate. Capitalism’s demand for growth and profit created a powerful incentive for imperialism, as colonies provided the resources, markets, and investment opportunities necessary to sustain the system. The alignment of capitalist interests with state power ensured that imperialist ventures were well-funded and politically supported. This period underscores the inextricable link between capitalism and imperialism, revealing how economic systems can shape global political landscapes and drive exploitation on a massive scale. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for analyzing the historical roots of modern global inequalities and the enduring legacy of colonial capitalism.

How to Verify Your Political Party Affiliation in New Jersey

You may want to see also

Government Policies: Legislative measures supporting or regulating capitalism in key nations during this period

In the late 19th century, particularly around 1882, key nations implemented legislative measures to support and regulate capitalism, reflecting the era's rapid industrialization and economic transformation. In the United States, the government adopted policies that fostered capitalist expansion, such as the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which regulated railroads to ensure fair competition and prevent monopolistic practices. This act was a response to the growing power of railroad barons and aimed to protect smaller businesses and consumers while maintaining a competitive market environment. Additionally, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 further solidified the government's role in regulating capitalism by prohibiting trusts and monopolies that restrained trade, ensuring a level playing field for businesses.

In Britain, the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, legislative measures focused on both supporting industrial growth and addressing social issues arising from capitalism. The Factories Act of 1878 regulated working conditions, limiting working hours for women and children, while the Trade Union Act of 1871 legalized trade unions, allowing workers to collectively bargain for better wages and conditions. These policies aimed to balance capitalist expansion with social welfare, ensuring that industrialization did not come at the expense of the working class. Additionally, the Public Health Act of 1875 addressed urban sanitation issues, indirectly supporting capitalism by creating healthier, more productive workforces.

Germany, under Otto von Bismarck, pursued a unique blend of capitalist support and social regulation known as "state socialism." The Social Insurance Acts of the 1880s, including health, accident, and old-age insurance, provided a safety net for workers, reducing social unrest and fostering a stable environment for capitalist growth. Simultaneously, the government invested heavily in infrastructure and education, laying the groundwork for Germany's industrial prowess. Legislative measures also protected domestic industries through tariffs, such as the 1879 tariff on grain and industrial goods, which shielded German businesses from foreign competition while promoting internal capitalist development.

In France, the government adopted policies to modernize its economy and compete with neighboring industrial powers. The Freycinet Plan of the 1870s involved massive state-led investments in railways, canals, and roads, stimulating economic growth and integrating regional markets. Additionally, the 1884 Law on Commercial Companies simplified the process of establishing joint-stock companies, encouraging entrepreneurship and capitalist ventures. However, France also faced challenges in balancing capitalist expansion with social stability, leading to policies like the 1884 Law on Workers' Associations, which legalized labor unions and aimed to mitigate class tensions.

In Japan, the Meiji Restoration period saw rapid industrialization supported by government policies that embraced capitalism. The Land Tax Reform of 1873 modernized land ownership, creating a market for land and capital. The government also established state-owned enterprises in key industries like shipping and textiles, later privatizing them to foster private capitalist development. The Factory Act of 1893 regulated labor conditions, though enforcement was limited, reflecting the government's priority on industrial growth over social welfare. These measures transformed Japan into a capitalist economy, positioning it as a rising industrial power by the late 19th century.

Overall, legislative measures during this period reflected a global trend of governments actively shaping capitalist systems through regulation, infrastructure investment, and social policies. While the approaches varied, the common goal was to harness capitalism's potential for economic growth while addressing its social and political challenges. These policies laid the foundation for the modern capitalist economies of the 20th century.

Understanding House of Representatives Political Parties and Their Roles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In 1882, key political figures associated with capitalism included leaders like Otto von Bismarck in Germany, who promoted state-supported capitalism, and Benjamin Disraeli in the United Kingdom, who balanced capitalist policies with social reforms. In the United States, President Chester A. Arthur oversaw a period of industrial expansion and capitalist growth.

In 1882, capitalism faced competition from ideologies such as socialism, led by figures like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and conservatism, which often resisted rapid industrialization. Additionally, anarchism and early forms of populism emerged as critiques of capitalist exploitation.

Capitalism influenced political policies in 1882 by promoting free trade, industrialization, and limited government intervention in economies. Policies often favored business interests, such as protective tariffs in the U.S. and infrastructure development in Europe, while labor rights and social welfare remained secondary concerns.