Political polls are a crucial tool for gauging public opinion on various issues, candidates, and policies, but the accuracy and reliability of these polls depend heavily on who participates in them. Typically, pollsters target a representative sample of the population, aiming to include individuals from diverse demographic groups, such as age, gender, race, education, and geographic location. However, not everyone is equally likely to respond to political polls; certain groups, such as older adults, more educated individuals, and those with stronger political affiliations, tend to participate more frequently. Conversely, younger people, minorities, and less politically engaged citizens are often underrepresented, which can skew results. Additionally, the rise of online polling has introduced new challenges, as response rates can vary significantly, and self-selection bias may occur when only those with strong opinions choose to participate. Understanding who answers political polls is essential for interpreting their findings and ensuring they accurately reflect the broader electorate.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Demographic Groups: Age, gender, race, education, income, and geographic location influence poll responses

- Political Affiliation: Party identification shapes answers, with partisanship often driving poll outcomes

- Survey Methodology: Phone, online, or in-person methods affect who participates and how they respond

- Motivation to Participate: Respondents may answer due to civic duty, personal interest, or incentives

- Non-Response Bias: Those who decline polls differ from participants, skewing results

Demographic Groups: Age, gender, race, education, income, and geographic location influence poll responses

Political poll responses are not uniform; they are a mosaic shaped by the diverse identities of respondents. Age, for instance, plays a pivotal role. Younger voters (18-29) are more likely to lean progressive, favoring policies like student debt relief and climate action, while older voters (65+) tend to prioritize fiscal conservatism and social stability. This age-based divide is not just theoretical—it’s quantifiable. A 2022 Pew Research poll revealed a 20-point gap between millennials and baby boomers on issues like government spending. Understanding these age-specific tendencies allows pollsters to predict not just who will answer, but how their answers will align with broader political trends.

Gender also significantly influences poll responses, though the dynamics are more nuanced than age. Women, statistically, are more likely to support social safety nets, healthcare expansion, and gender equality initiatives. Men, on the other hand, often lean toward law-and-order policies and economic deregulation. However, these trends are not absolute; intersectionality matters. A 2020 study by the Brookings Institution found that Black women, for example, are 30% more likely than white men to prioritize racial justice issues, highlighting how gender intersects with race to shape political priorities. Pollsters must account for these layers to avoid oversimplifying responses.

Race and ethnicity are among the most influential demographic factors in political polling. Hispanic voters, for instance, often prioritize immigration reform and economic opportunity, while Asian American voters may focus on education and healthcare. Black voters consistently rank racial equality and criminal justice reform as top concerns. These patterns are not monolithic—a first-generation immigrant’s perspective may differ sharply from a third-generation citizen’s—but they provide a framework for understanding group-specific priorities. Pollsters who ignore these racial and ethnic nuances risk misinterpreting data, leading to flawed predictions.

Education and income levels further complicate the demographic landscape. College-educated voters are more likely to support progressive policies like tax increases on the wealthy, while those without a college degree often favor economic populism. Similarly, high-income earners tend to oppose wealth redistribution, while low-income voters prioritize social welfare programs. These correlations are not deterministic but offer valuable insights. For example, a poll targeting low-income households in urban areas might overrepresent support for universal basic income, while a suburban, high-income sample could skew toward tax cuts.

Geographic location acts as a final, critical filter for poll responses. Urban voters typically lean left, favoring public transportation and environmental regulations, while rural voters often prioritize gun rights and agricultural subsidies. Suburban voters, a swing demographic, may shift based on local issues like school funding or zoning laws. These geographic differences are not just ideological—they’re practical. A poll conducted in California’s Central Valley will yield different results on water rights than one in Los Angeles. Pollsters must therefore consider not just where respondents live, but how their location shapes their political worldview.

In practice, these demographic factors are not siloed; they interact in complex ways. A 35-year-old, college-educated Black woman in Atlanta will likely have different priorities than a 60-year-old, high-school-educated white man in rural Montana. Pollsters must therefore employ stratified sampling, weighting responses to reflect the actual demographic makeup of the population. Without this precision, polls risk amplifying the voices of overrepresented groups while silencing others. By acknowledging and accounting for these demographic influences, pollsters can produce data that more accurately reflects the electorate’s diverse perspectives.

Evolving Politoed in Violet: A Step-by-Step Guide for Trainers

You may want to see also

Political Affiliation: Party identification shapes answers, with partisanship often driving poll outcomes

Political affiliation acts as a prism, refracting poll responses through the lens of party loyalty. Democrats and Republicans, for instance, consistently diverge on issues like healthcare, climate change, and economic policy. A 2021 Pew Research Center poll revealed a 40-percentage-point gap between the parties on government responsibility for healthcare, with 85% of Democrats and only 45% of Republicans supporting expanded federal involvement. This partisan divide isn’t accidental; it reflects the ideological frameworks parties promote, shaping how their members interpret and respond to survey questions.

Consider the mechanics of this influence. Party identification often precedes issue stances, meaning individuals adopt positions aligned with their party rather than forming opinions independently. This phenomenon, known as "party sorting," intensifies polarization and makes poll results predictable along partisan lines. For example, during election seasons, polls on presidential approval ratings routinely mirror party affiliation, with over 80% of respondents from the president’s party approving, compared to less than 20% from the opposing party. Such uniformity underscores how partisanship acts as a script, guiding answers more than personal beliefs or experiences.

However, this dynamic isn’t without nuance. Independents, who comprise roughly 40% of the U.S. electorate, often defy partisan expectations. Their responses can swing polls unpredictably, particularly on issues where party lines are less defined, such as foreign policy or education reform. Pollsters must account for this variability by oversampling Independents or weighting responses to ensure accuracy. Understanding this group’s behavior is critical, as their fluidity can tip poll outcomes in ways partisan responses cannot.

Practical implications abound for poll consumers. When interpreting results, scrutinize the partisan breakdown of respondents. A poll claiming 60% support for a policy is less meaningful if that support stems primarily from one party, with the other vehemently opposed. Cross-tabulating data by party affiliation reveals the true contours of public opinion, separating consensus from division. For instance, a 2020 Gallup poll showed 92% of Democrats and 18% of Republicans supported stricter gun laws, highlighting not unity but a stark partisan chasm.

In crafting polls, designers must mitigate partisan bias. Framing questions neutrally—avoiding loaded terms like "socialist" or "radical"—can reduce knee-jerk partisan reactions. Including demographic and ideological controls allows for more granular analysis, distinguishing between party loyalty and genuine opinion. Ultimately, recognizing the power of political affiliation transforms poll interpretation from a superficial reading of percentages into a nuanced understanding of the electorate’s fractured landscape.

China's Approach to Political Segregationists: Policies and Practices Explored

You may want to see also

Survey Methodology: Phone, online, or in-person methods affect who participates and how they respond

The choice of survey methodology—phone, online, or in-person—isn’t just a logistical decision; it fundamentally shapes who participates and how they respond. Phone surveys, for instance, tend to reach older demographics more reliably, as younger generations often screen calls or lack landlines. However, response rates for phone surveys have plummeted to around 6–9% in recent years, raising concerns about representativeness. Online surveys, on the other hand, attract tech-savvy participants, skewing toward younger, more educated, and urban populations. In-person surveys, while resource-intensive, yield higher response rates (up to 70%) and are more likely to engage hard-to-reach groups, such as non-English speakers or those without internet access. Each method, therefore, carries inherent biases that researchers must acknowledge to interpret results accurately.

Consider the impact of methodology on response behavior. Phone surveys often elicit more thoughtful answers due to the structured format and real-time interaction, but respondents may feel pressured to conform to social norms. Online surveys offer anonymity, encouraging candid responses, but they also risk superficial engagement, as participants can rush through questions. In-person surveys foster trust and allow for clarification, but the presence of an interviewer can introduce bias, particularly if the respondent feels judged. For example, a 2020 Pew Research study found that online respondents were 10% more likely to express extreme political views compared to phone respondents, highlighting how methodology can amplify or mute certain sentiments.

To mitigate these biases, researchers must strategically align their methodology with their target population. For instance, if polling on youth political engagement, an online survey might be most effective, but it should include mobile-optimized formats to capture a broader age range. Phone surveys remain valuable for reaching older voters but should incorporate shorter scripts and callbacks to improve participation. In-person surveys are ideal for diverse or marginalized communities but require trained interviewers sensitive to cultural nuances. Combining methods—a technique called mixed-mode surveying—can improve response rates and reduce bias, though it complicates data analysis. For example, a 2018 study on healthcare access used phone and in-person methods to achieve a 55% response rate, significantly higher than either method alone.

Practical tips for researchers include pre-testing survey instruments across all modes to ensure consistency, offering incentives tailored to the methodology (e.g., gift cards for online surveys, small tokens for in-person), and transparently reporting non-response rates to assess potential bias. For instance, weighting responses by demographic factors can help correct for underrepresentation, but this requires high-quality census data. Additionally, researchers should consider the timing of surveys: phone surveys during evenings or weekends, online surveys with reminders spaced 48 hours apart, and in-person surveys in locations convenient to the target population.

Ultimately, the methodology isn’t neutral—it’s a critical variable that influences both who answers and what they say. By understanding these dynamics, researchers can design surveys that minimize bias and maximize validity. For example, a political poll aiming to predict election outcomes might use a mixed-mode approach, combining online surveys for rapid data collection with phone calls to older voters and in-person interviews in rural areas. Such a strategy ensures a more comprehensive and accurate snapshot of public opinion, demonstrating that the method is as important as the message.

Mastering Political Savvy: Strategies to Enhance Your Astuteness and Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Motivation to Participate: Respondents may answer due to civic duty, personal interest, or incentives

Political poll respondents often cite a sense of civic duty as their primary motivation. This group views participation as a fundamental responsibility, akin to voting or staying informed. For them, answering polls is a way to contribute to the democratic process, ensuring their voice is heard and their community’s needs are represented. Research shows that older adults, particularly those aged 55 and above, are more likely to participate out of this obligation, with studies indicating they make up over 40% of poll respondents in this category. To tap into this motivation, pollsters can frame participation as a civic act, emphasizing its role in shaping public discourse and policy.

Personal interest drives another segment of respondents, particularly those deeply engaged with political issues or current events. These individuals are often well-informed, follow politics closely, and see polls as an opportunity to express their opinions on matters they care about. Younger respondents, aged 18–34, are more likely to fall into this category, with data suggesting they comprise nearly 35% of poll participants motivated by personal interest. Pollsters can engage this group by focusing on timely, relevant questions and using platforms they frequent, such as social media or news apps. Offering detailed feedback or results after participation can also satisfy their curiosity and encourage repeat engagement.

Incentives play a significant role in motivating respondents who might otherwise be indifferent to political polls. These incentives range from small financial rewards, like gift cards or cash, to non-monetary benefits, such as entering a prize draw or receiving exclusive content. For instance, offering a $5 Amazon gift card for completing a 10-minute survey has been shown to increase response rates by up to 25%. However, caution is necessary: over-reliance on incentives can skew results, attracting participants more interested in the reward than the topic. To mitigate this, pollsters should ensure incentives are modest and clearly communicate the survey’s purpose to maintain respondent focus.

Comparing these motivations reveals distinct respondent profiles and strategies for engagement. Civic duty appeals to older, more traditional participants, while personal interest resonates with younger, politically engaged individuals. Incentives, on the other hand, are a versatile tool that can attract a broader audience but require careful implementation. For maximum effectiveness, pollsters should tailor their approach based on the target demographic. For example, a survey aimed at seniors might emphasize civic responsibility, while one targeting millennials could highlight its relevance to trending issues. By understanding these motivations, pollsters can design more inclusive and accurate surveys that capture a diverse range of perspectives.

Do CIA Political Analysts Travel? Exploring Their Global Roles and Responsibilities

You may want to see also

Non-Response Bias: Those who decline polls differ from participants, skewing results

Political pollsters often face a silent adversary: non-response bias. This occurs when those who decline to participate in surveys differ systematically from those who do. For instance, a Pew Research Center study found that younger adults, racial minorities, and individuals with lower educational attainment are less likely to answer polls. These groups, however, often hold distinct political views, meaning their absence can skew results toward the perspectives of older, whiter, and more educated respondents. This disparity isn’t just demographic—it’s ideological, creating a distorted mirror of public opinion.

Consider the mechanics of non-response bias in action. A poll on healthcare policy might attract respondents who feel strongly about the issue, while those indifferent or overwhelmed by the topic opt out. The result? A survey that overrepresents passionate voices and underrepresents the silent majority. Pollsters sometimes attempt to correct this by weighting responses to match known population demographics, but this method assumes they know who isn’t answering—a risky gamble. Without accurate data on non-respondents, even weighted polls can mislead.

Practical steps can mitigate non-response bias, though they’re not foolproof. First, diversify outreach methods: combine phone calls, emails, and in-person interviews to reach broader audiences. Second, offer incentives like gift cards or charitable donations to boost participation rates. Third, conduct follow-up surveys targeting non-respondents to understand their reluctance. For example, a 2020 study found that 30% of non-respondents cited lack of time as their reason for declining, while 20% expressed distrust in pollsters. Addressing these barriers—through shorter surveys or transparency initiatives—could improve response rates.

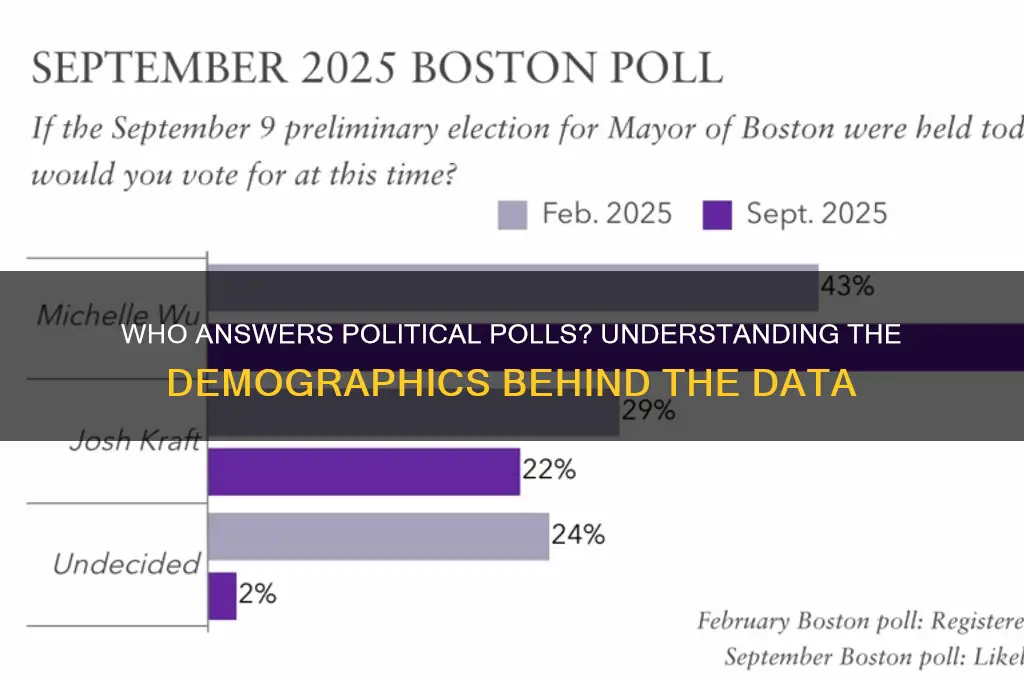

A comparative analysis highlights the stakes. In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, polls underestimated support for Donald Trump, partly due to non-response bias. Many working-class voters, disillusioned with politics, declined to participate, while more vocal groups dominated surveys. Conversely, the 2012 election saw higher response rates among younger voters, accurately predicting Barack Obama’s victory. This contrast underscores how non-response bias can swing results, depending on which groups opt out. Pollsters must remain vigilant, adapting strategies to capture the elusive voices that shape elections.

Finally, a persuasive argument: ignoring non-response bias undermines democracy. Polls influence policy decisions, media narratives, and voter perceptions. When results are skewed, marginalized groups are further silenced, and public discourse becomes a monologue of the privileged. Pollsters, journalists, and citizens must demand transparency in survey methodologies and push for inclusive practices. Only then can political polls reflect the true diversity of opinion, ensuring that every voice—even the quiet ones—is heard.

ESPN's Political Shift: How Sports Media Embraced Partisan Divide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political polls are answered by a diverse group of individuals, including registered voters, likely voters, and sometimes the general public, depending on the poll's purpose.

Yes, reputable political polls use random sampling methods to ensure the results are representative of the population being studied.

No, political polls aim to include respondents from all political affiliations to provide a balanced and accurate representation of public opinion.

Young people may be less likely to answer political polls compared to older demographics, but efforts are made to include all age groups for comprehensive results.

Some polls may offer small incentives like gift cards or entries into drawings, but most respondents participate voluntarily without compensation.