By 1828, the American political landscape had solidified into two distinct parties: the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which emerged in opposition to Jackson’s policies. The Democratic Party, rooted in Jeffersonian ideals, championed states’ rights, limited federal government, and the interests of the common man, while the Whigs, a coalition of National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and others, advocated for a stronger federal government, internal improvements, and a national bank. The 1828 presidential election, a pivotal contest between Jackson and John Quincy Adams, marked the formalization of this two-party system, setting the stage for decades of political rivalry and ideological debate in the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Names of the Parties | Democratic Party (formerly Democratic-Republican Party) and Whig Party |

| Founding Period | Early 1820s (Democratic Party) and 1834 (Whig Party, though roots in 1828) |

| Key Leaders | Andrew Jackson (Democratic Party), Henry Clay and Daniel Webster (Whig Party) |

| Ideological Focus | Democratic Party: States' rights, limited federal government, agrarianism |

| Whig Party: National bank, industrialization, federal infrastructure | |

| Base of Support | Democratic Party: Farmers, Western and Southern states |

| Whig Party: Urban merchants, Northern states, industrialists | |

| Economic Policies | Democratic Party: Opposed national bank, favored decentralized economy |

| Whig Party: Supported national bank, tariffs, and internal improvements | |

| Social Policies | Democratic Party: Emphasized individual liberty and local control |

| Whig Party: Focused on moral reform and modernization | |

| Electoral Strength | Democratic Party: Dominant in presidential elections (e.g., 1828, 1832) |

| Whig Party: Strong in Congress and state legislatures | |

| Legacy | Democratic Party: Evolved into the modern Democratic Party |

| Whig Party: Dissolved by the 1850s, with members joining Republicans |

Explore related products

$48.88 $55

What You'll Learn

- Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson, emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government

- National Republican Party: Led by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, supported national economic development and infrastructure

- Democratic Party Evolution: Emerged from Democratic-Republicans, championed Jacksonian democracy and expanded suffrage

- Jacksonian Democracy: Andrew Jackson's movement, focused on common man's rights and opposition to elites

- Second Party System: Defined by Democrats and National Republicans (later Whigs), shaped 1828-1854 politics

Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson, emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government

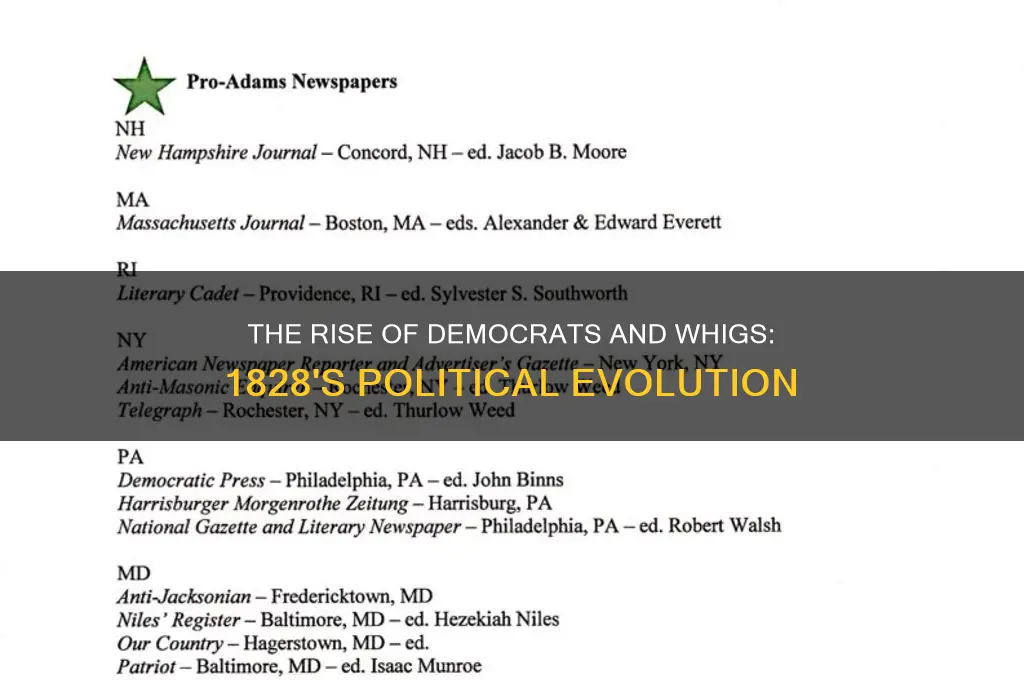

By 1828, the American political landscape had solidified around two dominant parties: the Democratic-Republican Party and the National Republicans (later known as the Whigs). The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson, emerged as a counter to the Federalist Party’s vision of a strong central government. Jefferson’s party championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a limited federal government, principles that resonated deeply with the rural and agricultural majority of early 19th-century America. This ideology not only shaped the party’s platform but also laid the groundwork for future political movements, including the modern Democratic Party.

To understand the Democratic-Republican Party’s appeal, consider its core tenets. First, its emphasis on states’ rights was a direct response to Federalist policies that centralized power in Washington. Jefferson believed that states, not the federal government, should hold primary authority over most domestic issues. This principle was particularly attractive to farmers and rural communities, who feared federal overreach into their local economies and lifestyles. For example, the party opposed the national bank and internal improvements funded by the federal government, arguing that such initiatives encroached on state sovereignty.

Second, the party’s focus on agrarian interests reflected the realities of early American society. In 1828, over 90% of the population lived in rural areas, and agriculture was the backbone of the economy. Jefferson’s vision of a nation of independent farmers, free from the influence of industrial and financial elites, resonated with this demographic. The party supported policies like low tariffs, which protected farmers from foreign competition, and land expansion, which provided new opportunities for settlement and cultivation. These measures were not just economic policies but also a cultural statement about the ideal American citizen.

However, the Democratic-Republican Party’s commitment to limited federal government was not without its challenges. While this principle aligned with Jeffersonian ideals, it often clashed with the practical needs of a growing nation. For instance, the party’s opposition to federal infrastructure projects, such as roads and canals, hindered economic development in some regions. This tension between ideology and practicality eventually contributed to the party’s evolution into the Democratic Party under Andrew Jackson, who expanded federal power in certain areas while maintaining its populist appeal.

In conclusion, the Democratic-Republican Party’s emphasis on states’ rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government made it a defining force in early American politics. Its principles not only addressed the immediate concerns of its constituents but also shaped the nation’s political identity. By 1828, the party had become a cornerstone of the two-party system, its legacy enduring in the modern Democratic Party’s focus on grassroots democracy and economic equality. Understanding its origins and ideology provides valuable insights into the evolution of American political thought.

The Origins of Political Parties: A Historical Journey

You may want to see also

National Republican Party: Led by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, supported national economic development and infrastructure

By 1828, the American political landscape had crystallized into two dominant parties: the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the National Republican Party, spearheaded by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. While the Democrats championed states’ rights and agrarian interests, the National Republicans emerged as staunch advocates for national economic development and infrastructure. This party, often referred to as the "Adams Party," represented a coalition of former Federalists and disaffected Democratic-Republicans who prioritized a strong federal government to foster economic growth.

The National Republican Party’s platform was rooted in the American System, a tripartite economic plan devised by Henry Clay. This system emphasized three key components: a protective tariff to shield American industries from foreign competition, a national bank to stabilize the currency and credit, and federal funding for internal improvements such as roads, canals, and bridges. These policies were designed to create a self-sustaining economy, reduce dependence on European goods, and connect the geographically dispersed nation. For instance, the party supported the construction of the Cumberland Road, a vital east-west artery, and the Erie Canal, which revolutionized trade between the Midwest and the East Coast.

John Quincy Adams, as president from 1825 to 1829, embodied the party’s vision. His inaugural address outlined an ambitious agenda for internal improvements, education, and scientific advancement. However, his proposals often faced opposition from Jacksonian Democrats, who viewed federal involvement in such projects as overreach. Despite this, Adams and Clay remained committed to their cause, arguing that infrastructure was not merely a matter of convenience but a necessity for national unity and prosperity. Their efforts laid the groundwork for later federal investments in railroads and telegraph lines, which transformed the American economy in the mid-19th century.

To understand the National Republicans’ impact, consider their role in shaping modern infrastructure policy. Their advocacy for federal funding of public works contrasts sharply with the prevailing laissez-faire attitudes of the time. Today, this legacy is evident in programs like the Federal Highway Administration and the Department of Transportation, which continue to rely on federal investment. For those interested in replicating their approach, a practical tip is to study the American System’s principles and apply them to contemporary challenges, such as renewable energy infrastructure or broadband expansion.

In conclusion, the National Republican Party’s focus on national economic development and infrastructure was both visionary and pragmatic. Led by Adams and Clay, they championed policies that, while contentious in their time, proved essential for America’s industrialization and cohesion. Their story serves as a reminder that federal leadership in economic planning can drive long-term growth and connectivity, offering valuable lessons for policymakers and historians alike.

Understanding Political Party Lines: Definitions, Roles, and Real-World Impact

You may want to see also

Democratic Party Evolution: Emerged from Democratic-Republicans, championed Jacksonian democracy and expanded suffrage

By 1828, the American political landscape had crystallized into two dominant parties: the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Democratic Party, however, stands out for its unique evolution from the Democratic-Republican Party, its embrace of Jacksonian democracy, and its role in expanding suffrage. This transformation was not merely a rebranding but a fundamental shift in ideology and political strategy, reflecting the changing dynamics of early 19th-century America.

The Democratic Party’s origins trace back to the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. This party, which dominated the early republic, emphasized states’ rights, limited federal government, and agrarian interests. However, by the late 1820s, internal divisions over issues like tariffs, internal improvements, and the role of the presidency led to its fracture. The emergence of Andrew Jackson as a political force catalyzed this transformation. Jackson’s populist appeal and his vision of a more inclusive democracy resonated with a growing electorate, particularly in the South and West. The Democratic Party, formally organized in 1828, became the vehicle for Jacksonian democracy, which championed the common man against what Jackson perceived as the elitism of the Eastern establishment.

Jacksonian democracy was more than a slogan; it was a political philosophy that redefined American governance. It emphasized the sovereignty of the people, expanded suffrage to nearly all white men (regardless of property ownership), and sought to dismantle what Jackson saw as the corrupting influence of special interests. The party’s 1828 platform reflected these ideals, advocating for the rotation of officeholders, the abolition of the national bank, and the protection of states’ rights. Jackson’s election that year marked the triumph of this ideology, as he portrayed himself as the champion of the ordinary citizen against the entrenched power of the elite.

The expansion of suffrage was a cornerstone of the Democratic Party’s evolution. By the 1820s, most states had eliminated property requirements for voting, a shift that dramatically increased the electorate. The Democrats capitalized on this trend, mobilizing newly enfranchised voters and building a broad-based coalition. This strategy not only secured Jackson’s victory in 1828 but also laid the groundwork for the party’s dominance in the antebellum era. However, it’s crucial to note that this expansion of democracy was limited to white men; women, African Americans, and Native Americans remained excluded from the political process, a stark limitation of Jacksonian ideals.

In practical terms, the Democratic Party’s evolution offers a blueprint for political adaptation. By aligning with the aspirations of a changing electorate and leveraging populist rhetoric, the party secured its relevance in a rapidly evolving nation. For modern political strategists, this history underscores the importance of understanding demographic shifts and crafting policies that resonate with emerging voter blocs. However, it also serves as a cautionary tale: the exclusionary nature of Jacksonian democracy highlights the dangers of pursuing inclusivity without addressing systemic inequalities. As we reflect on the Democratic Party’s evolution, we are reminded that true democracy requires not just expanding access but ensuring equity for all.

State vs. National Political Parties: Are Their Identities Truly Aligned?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Jacksonian Democracy: Andrew Jackson's movement, focused on common man's rights and opposition to elites

By 1828, American politics had crystallized into two dominant parties: the Democratic-Republicans and the National Republicans, later known as the Whigs. This period marked a shift from elite-dominated governance to a more populist approach, largely due to the rise of Jacksonian Democracy. Led by Andrew Jackson, this movement championed the rights of the "common man" and fiercely opposed the influence of political and economic elites. Jackson’s election in 1828 symbolized a seismic change in American democracy, as he rallied farmers, laborers, and frontiersmen against the entrenched power of bankers, industrialists, and established politicians.

At its core, Jacksonian Democracy was a reaction to the perceived corruption of the political system. Jackson’s supporters viewed institutions like the Second Bank of the United States as tools of the wealthy, designed to exploit the masses. His veto of the Bank’s recharter in 1832 was a defining moment, signaling his commitment to dismantling structures that favored the elite. This move, though controversial, resonated with ordinary Americans who felt marginalized by the nation’s economic and political systems. Jackson’s policies, such as the redistribution of federal land and the expansion of suffrage, aimed to empower the average citizen, though they often excluded marginalized groups like women, Native Americans, and enslaved Africans.

To understand Jacksonian Democracy’s impact, consider its practical implications. For instance, the movement’s emphasis on universal white male suffrage led to a dramatic increase in voter participation, transforming elections into mass events. However, this expansion of democracy was not without its contradictions. While Jackson championed the common man, his policies, such as the Indian Removal Act of 1830, resulted in the forced displacement of Native American tribes, revealing the movement’s limitations and moral ambiguities. This duality—progress for some at the expense of others—underscores the complexity of Jackson’s legacy.

Critics argue that Jacksonian Democracy was less about equality and more about shifting power from one elite group to another. Jackson’s reliance on patronage and his authoritarian tendencies, such as his defiance of the Supreme Court in the Cherokee Nation case, suggest that his movement was not as democratic as it claimed. Yet, for many Americans at the time, Jackson represented a break from the past, a leader who spoke their language and fought their battles. His presidency marked the beginning of a new era in American politics, where the voice of the common man, however imperfectly defined, began to shape the nation’s destiny.

In retrospect, Jacksonian Democracy was both a triumph and a cautionary tale. It expanded political participation and challenged the dominance of elites, but it also perpetuated inequalities and injustices. For modern readers, the movement offers a reminder that democracy is an evolving project, requiring constant vigilance and inclusivity. As we reflect on the two political parties of 1828, Jackson’s legacy prompts us to ask: Who is included in the “common man,” and at whose expense does progress come? These questions remain as relevant today as they were two centuries ago.

Understanding Liberals: Their Political Party Affiliation Explained in Detail

You may want to see also

Second Party System: Defined by Democrats and National Republicans (later Whigs), shaped 1828-1854 politics

By 1828, the American political landscape had crystallized into two dominant parties: the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the National Republicans, later known as the Whigs, spearheaded by figures like Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. This era, known as the Second Party System, marked a significant shift from the earlier Federalist-Republican rivalry, redefining political ideologies and voter engagement. The 1828 election, a bitter contest between Jackson and Adams, exemplified the emerging divide: Jackson’s Democrats championed states’ rights, limited federal government, and the interests of the "common man," while the National Republicans advocated for internal improvements, protective tariffs, and a stronger central government.

The Democrats, rooted in Jacksonian populism, appealed to farmers, laborers, and the expanding frontier population. Their platform emphasized individual liberty, opposition to elitism, and skepticism of centralized power. Jackson’s victory in 1828 solidified the Democrats as a force for egalitarianism, though critics accused them of pandering to the majority at the expense of minority rights, as seen in policies like the Indian Removal Act. Meanwhile, the National Republicans, later Whigs, drew support from urban merchants, industrialists, and those favoring federal intervention in economic development. Their vision of a modernizing America clashed with the Democrats’ agrarian focus, creating a dynamic tension that defined the period.

The Second Party System was not merely a battle of ideologies but also a transformation in political participation. The 1828 election saw a dramatic expansion of the electorate, as property requirements for voting were relaxed in many states, allowing more white men to cast ballots. This democratization of politics fueled the rise of party machines, rallies, and newspapers as tools for mobilization. The Whigs, in particular, excelled in organizing urban voters through local committees and charismatic leadership, while the Democrats harnessed grassroots enthusiasm for Jackson’s persona. This era laid the groundwork for modern campaign strategies, emphasizing voter turnout and party loyalty.

Despite their differences, both parties grappled with the issue of slavery, though it was not yet the defining fault line it would become in the 1850s. The Democrats’ commitment to states’ rights aligned with Southern interests, while the Whigs’ focus on economic development often sidestepped the slavery question to maintain a fragile national coalition. This uneasy balance began to unravel by the 1850s, as the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act exposed irreconcilable divisions within the Whig Party, leading to its collapse. The Second Party System thus ended not with a bang but with a splintering of the Whigs, paving the way for the rise of the Republican Party and the realignment of American politics around the slavery issue.

In retrospect, the Second Party System was a crucible for modern American politics, shaping how parties organize, mobilize, and compete. The Democrats and Whigs not only defined the political debates of their time but also established enduring patterns of partisanship and ideology. Their rivalry reflected the nation’s struggle to reconcile democracy, economic growth, and regional interests—a tension that continues to resonate today. Understanding this era offers insights into the roots of contemporary political divisions and the challenges of balancing unity with diversity in a sprawling republic.

Mark Ciavarella Jr.'s Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

By 1828, the two major political parties that had evolved were the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which emerged as an opposition to Jacksonian policies.

The Democratic Party advocated for states' rights, limited federal government, and the expansion of democracy, while the Whigs supported a stronger federal government, economic modernization, and internal improvements.

Andrew Jackson was the central figure of the Democratic Party, while Henry Clay and Daniel Webster were prominent leaders of the Whig Party.

The collapse of the Era of Good Feelings and the contentious presidential election of 1824, which highlighted divisions over political ideology and regional interests, led to the emergence of these two parties.

The Democratic Party favored agrarian interests and opposed federal intervention in the economy, while the Whigs supported industrialization, tariffs, and federal funding for infrastructure projects.

![Les Poletais, comédie-vaudeville en deux parties 1828 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61IX47b4r9L._AC_UY218_.jpg)