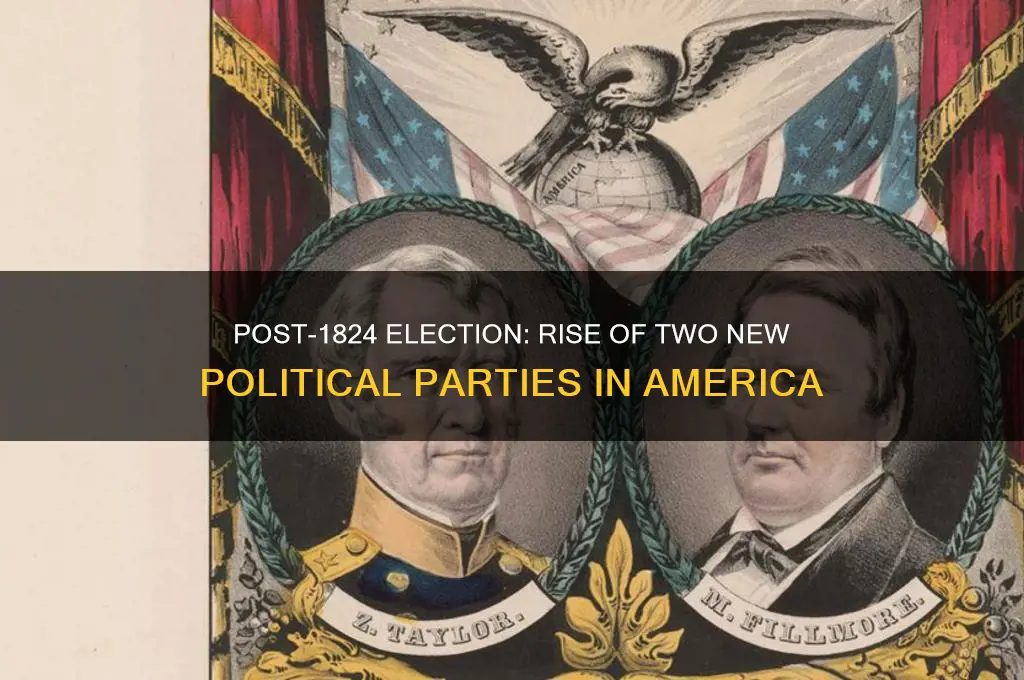

The election of 1824 marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as it led to the emergence of two distinct political factions that would shape the nation's future. Following the contentious election, which lacked a clear majority and was ultimately decided by the House of Representatives in favor of John Quincy Adams, the Democratic-Republican Party began to fracture. Supporters of Andrew Jackson, who had won the popular and electoral vote but failed to secure the presidency, coalesced into the Democratic Party, championing states' rights, limited federal government, and the interests of the common man. Meanwhile, backers of Adams and Henry Clay, who had played a key role in Adams's victory, formed the National Republican Party (later known as the Whig Party), advocating for a stronger federal government, internal improvements, and economic modernization. These two parties would dominate American politics for decades, setting the stage for the Second Party System and defining the ideological divides of the early 19th century.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Names of Parties | Democratic Party and Whig Party |

| Emergence Year | 1828 (Democratic Party) and 1833-1834 (Whig Party) |

| Founding Leaders | Andrew Jackson (Democratic Party), Henry Clay and Daniel Webster (Whig Party) |

| Ideological Roots | Democratic Party: Jacksonian Democracy; Whig Party: National Republican Party |

| Core Principles | Democratic Party: States' rights, limited federal government; Whig Party: Strong federal government, economic modernization |

| Key Policies | Democratic Party: Opposition to national bank; Whig Party: Support for national bank, infrastructure development |

| Support Base | Democratic Party: Farmers, workers, and the "common man"; Whig Party: Urban professionals, business leaders, and industrialists |

| Geographic Strength | Democratic Party: South and West; Whig Party: Northeast and parts of the Midwest |

| Notable Figures | Democratic Party: Martin Van Buren, James K. Polk; Whig Party: William Henry Harrison, John Tyler |

| Decline | Whig Party dissolved in the 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery; Democratic Party evolved into its modern form |

| Legacy | Democratic Party remains one of the two major U.S. parties; Whig Party's ideas influenced the Republican Party |

Explore related products

$20.15 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Democratic-Republican Party Split: Factions divided over John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson’s presidential bids

- Democratic Party Formation: Jackson’s supporters created the Democratic Party to challenge Adams’ administration

- National Republican Party Rise: Adams’ backers formed the National Republican Party to support his policies

- Spoils System Debate: Jackson’s Democrats championed rotating government jobs, contrasting Adams’ merit-based approach

- Tariff and Economy: Disagreements over tariffs and economic policies fueled party divisions post-1824

Democratic-Republican Party Split: Factions divided over John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson’s presidential bids

The 1824 presidential election marked a turning point in American politics, as it exposed deep fractures within the dominant Democratic-Republican Party. The party, which had enjoyed nearly unchallenged power since the early 1800s, found itself divided over two prominent figures: John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. This split was not merely a clash of personalities but a reflection of broader ideological and regional tensions that would reshape the nation’s political landscape.

At the heart of the division was the contentious outcome of the 1824 election. Neither Adams nor Jackson secured a majority in the Electoral College, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives. Henry Clay, another candidate and Speaker of the House, threw his support behind Adams, who was then elected. Jackson’s supporters cried foul, accusing Adams and Clay of a "corrupt bargain." This perceived injustice fueled resentment among Jackson’s backers, who saw their candidate as the true voice of the people, while Adams was viewed as an elitist backed by the establishment.

The ideological differences between the factions were stark. Adams’ supporters, often referred to as National Republicans, championed a strong federal government, internal improvements, and economic modernization. They appealed to the emerging industrial and commercial classes, particularly in the Northeast. In contrast, Jackson’s followers, who would later form the Democratic Party, emphasized states’ rights, limited government, and the interests of the "common man." Their base was rooted in the South and West, where agrarian economies and frontier values dominated.

This split was not just ideological but also personal. Jackson’s military heroics and self-fashioned image as a man of the people resonated deeply with voters, while Adams’ intellectual demeanor and aristocratic background alienated many. The rivalry between the two men and their supporters intensified after 1824, setting the stage for the 1828 election, which would solidify the emergence of the Democratic and National Republican Parties.

Practical takeaways from this period highlight the importance of understanding how personal rivalries and ideological differences can fracture even the most dominant political movements. For modern political strategists, the lesson is clear: unity within a party is fragile and can be shattered by perceived injustices or competing visions. To prevent such splits, leaders must address internal divisions early and foster inclusive platforms that appeal to diverse factions. By studying the Democratic-Republican Party’s dissolution, we gain insight into the enduring dynamics of American politics and the challenges of maintaining party cohesion in the face of competing interests.

Bridging the Divide: Can Opposing Political Parties Coexist Peacefully?

You may want to see also

Democratic Party Formation: Jackson’s supporters created the Democratic Party to challenge Adams’ administration

The 1824 presidential election, often called the "corrupt bargain," left a bitter taste in the mouths of Andrew Jackson's supporters. Jackson, a war hero and populist figure, had won the popular and electoral vote but failed to secure a majority, throwing the election to the House of Representatives. There, Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House and a Jackson rival, threw his support behind John Quincy Adams, who was subsequently elected president. This perceived backroom deal fueled outrage among Jackson's backers, who saw it as a subversion of the will of the people.

From this disillusionment, the Democratic Party was born. Jackson's supporters, a diverse coalition of western farmers, southern planters, and urban workers, rallied around his candidacy and the principles he embodied: states' rights, limited federal government, and opposition to elitism. They saw Adams and the National Republicans as representatives of a privileged eastern establishment, out of touch with the needs and aspirations of the common man.

The formation of the Democratic Party was a strategic response to this perceived threat. Jackson's supporters understood that to challenge Adams' administration effectively, they needed a cohesive organization capable of mobilizing voters, raising funds, and articulating a clear alternative vision for the country. They built a party machine that emphasized grassroots participation, local caucuses, and a strong national committee. This structure allowed them to tap into the growing discontent with Adams' policies, particularly his support for internal improvements and protective tariffs, which were seen as benefiting the North at the expense of the South and West.

The Democratic Party's platform reflected Jackson's populist appeal. They championed states' rights, arguing that the federal government should have limited power over individual states. They opposed federal funding for internal improvements, believing that such projects should be left to state and local governments. They also advocated for the expansion of democracy, supporting the extension of voting rights to all white men, regardless of property ownership.

The 1828 election became a referendum on the Adams administration and the principles of the newly formed Democratic Party. Jackson's campaign, fueled by the organizational strength of the party and his own charismatic appeal, proved successful. He defeated Adams in a landslide, marking the ascendancy of the Democratic Party and the beginning of the Second Party System in American politics. The party's formation was a direct response to the perceived injustices of the 1824 election, and its success demonstrated the power of grassroots organization and populist rhetoric in shaping the American political landscape.

Understanding Political Party Platforms: A Comprehensive Worksheet Guide

You may want to see also

National Republican Party Rise: Adams’ backers formed the National Republican Party to support his policies

The 1824 presidential election, often dubbed the "Revolution of 1824," shattered the Era of Good Feelings and its one-party dominance. From its contentious aftermath emerged two distinct political factions: the Democratic Party and the National Republican Party. While the former, led by Andrew Jackson, capitalized on populist sentiments, the latter coalesced around John Quincy Adams and his vision for a more active federal government.

The National Republican Party, born from the ashes of the Adams campaign, wasn't merely a reactionary force. It represented a deliberate effort by Adams' supporters to institutionalize his policy agenda. This agenda, characterized by internal improvements, protective tariffs, and a strong national bank, stood in stark contrast to Jackson's laissez-faire approach.

Imagine a political landscape devoid of the familiar red and blue divisions. The National Republican Party, with its emphasis on national development and economic intervention, would be akin to a modern-day centrist or even center-left party. They championed infrastructure projects like roads and canals, believing them essential for connecting the vast American frontier and fostering economic growth. This focus on internal improvements, however, came at a cost, often clashing with states' rights advocates who feared federal overreach.

The party's formation wasn't without its challenges. Adams, though intellectually formidable, lacked the charisma and popular appeal of Jackson. The National Republicans, therefore, had to rely on a network of local leaders and a well-organized party structure to disseminate their message and mobilize voters. This marked a significant shift in American politics, moving away from the loose coalitions of the past towards a more disciplined and organized party system.

The National Republican Party's rise was short-lived, ultimately succumbing to the Jacksonian tide in the 1832 election. However, its legacy is undeniable. It laid the groundwork for future Whig and later Republican parties, shaping the American political landscape for decades to come. Their emphasis on national development and a strong federal government continues to resonate in contemporary debates, reminding us that the echoes of the 1824 election still reverberate in our political discourse.

Exploring the Grassroots: Understanding the Smallest Political Party Units

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spoils System Debate: Jackson’s Democrats championed rotating government jobs, contrasting Adams’ merit-based approach

The 1824 election reshaped American politics, birthing two dominant parties: the Democratic-Republicans, fracturing into Andrew Jackson’s Democrats and John Quincy Adams’ National Republicans (later Whigs). Central to their rivalry was the spoils system debate, a clash of ideologies over how to staff the federal government. Jackson’s Democrats championed rotating government jobs, arguing it democratized power and rewarded loyal supporters. Adams, in contrast, favored a merit-based approach, prioritizing competence and experience. This divide wasn’t merely administrative—it reflected deeper disagreements about the role of government, the nature of democracy, and the balance between patronage and professionalism.

Jackson’s spoils system, often dubbed "rotation in office," was rooted in his populist ethos. He believed government jobs should be accessible to ordinary citizens, not monopolized by elites. By regularly replacing federal employees with party loyalists, Jackson aimed to break the stranglehold of entrenched bureaucrats and ensure the government reflected the will of the people. Critics, however, saw this as cronyism, rewarding political favoritism over skill. Yet, for Jackson’s supporters, it was a tool of democratization, decentralizing power and preventing the rise of a permanent ruling class. Practical implementation involved short-term appointments and mass firings of Adams-era officials, a strategy both bold and divisive.

Adams’ merit-based approach, championed by his National Republicans, emphasized expertise and continuity. He argued that government positions required specialized knowledge and that frequent turnover would undermine efficiency. Adams’ system, influenced by Enlightenment ideals, sought to create a professional bureaucracy insulated from political whims. This approach appealed to urban elites and those who valued stability, but it alienated rural voters who saw it as exclusionary. The debate wasn’t just theoretical—it had tangible consequences. For instance, Adams’ appointment of skilled but politically neutral officials often clashed with Jackson’s vision of a government directly accountable to the electorate.

The spoils system debate also highlighted broader tensions in American democracy. Jackson’s approach aligned with his belief in majority rule and the sovereignty of the people, while Adams’ model reflected a more technocratic vision. These contrasting philosophies shaped policy and public perception. Jackson’s victory in 1828 cemented the spoils system as a cornerstone of Democratic Party politics, though it later drew criticism for corruption and inefficiency. Adams’ legacy, meanwhile, influenced the Whig Party’s emphasis on internal improvements and a strong federal government. Both approaches left indelible marks on American political culture, framing ongoing debates about the role of patronage versus professionalism in governance.

In practice, the spoils system debate offers lessons for modern governance. Jackson’s model, while inclusive, risked undermining institutional expertise, a cautionary tale for today’s leaders balancing diversity with competence. Adams’ approach, though idealistic, struggled to connect with a skeptical public, underscoring the importance of political legitimacy. For policymakers, the key takeaway is the need for balance—ensuring government is both representative and effective. Implementing hybrid models, such as term limits for political appointees paired with merit-based hiring for technical roles, could bridge this historic divide. Ultimately, the spoils system debate reminds us that the structure of governance is as much about values as it is about administration.

Exploring Louisiana's Dominant Political Party: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Tariff and Economy: Disagreements over tariffs and economic policies fueled party divisions post-1824

The election of 1824 marked a turning point in American politics, giving rise to the Democratic Party and the National Republican Party (later known as the Whigs). At the heart of their divergence lay bitter disputes over tariffs and economic policies, which not only defined their platforms but also deepened regional and ideological divides. These disagreements were not merely academic; they had tangible impacts on industries, livelihoods, and the nation’s economic trajectory.

Consider the Tariff of 1828, often dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations" by its Southern critics. Designed to protect Northern manufacturing interests by imposing steep duties on imported goods, it disproportionately burdened the agrarian South, which relied heavily on imported manufactured products and faced reduced demand for its raw cotton exports. This economic imbalance fueled resentment, with Southern politicians denouncing the tariff as a tool of Northern exploitation. The Democratic Party, led by figures like Andrew Jackson, championed states’ rights and opposed such federal interventions, appealing to Southern and Western agrarian interests. In contrast, the National Republicans, under Henry Clay’s American System, advocated for protective tariffs, internal improvements, and a strong national bank to foster industrial growth, aligning with Northern and commercial elites.

The clash over tariffs was not just regional but also ideological, reflecting competing visions of America’s economic future. For the National Republicans, tariffs were a cornerstone of national development, ensuring self-sufficiency and industrial expansion. For the Democrats, they symbolized federal overreach and economic inequality, stifling the South’s agrarian economy while enriching Northern manufacturers. This divide was further exacerbated by debates over the Second Bank of the United States, which Democrats viewed as a corrupt institution favoring the wealthy, while National Republicans saw it as essential for stabilizing the economy.

Practical implications of these disagreements were far-reaching. Farmers in the South faced higher costs for essential goods, while Northern factory owners enjoyed protected markets. The resulting economic strain contributed to the Nullification Crisis of 1832, when South Carolina declared the tariffs null and void, threatening secession. While the crisis was temporarily defused, it underscored the depth of the partisan rift. To navigate such tensions today, policymakers might consider targeted regional incentives or graduated tariff structures to balance protectionism with fairness, ensuring no single region bears an undue burden.

In conclusion, the tariff and economic disputes post-1824 were not mere policy differences but reflections of fundamental disagreements about America’s identity and future. They shaped the Democratic and National Republican Parties, setting the stage for decades of political conflict. Understanding this history offers valuable lessons for modern economic policy, emphasizing the need for inclusivity and regional equity in crafting legislation.

Rosa Parks' Political Legacy: Activism, Civil Rights, and Social Justice

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two political parties that emerged after the election of 1824 were the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which formed in opposition to Jackson's policies.

The parties formed due to the contentious 1824 election, which was decided in the House of Representatives after no candidate secured a majority of electoral votes. This led to divisions over John Quincy Adams's victory and Andrew Jackson's claims of a "corrupt bargain," sparking the realignment of political factions.

The 1824 election exposed deep ideological and regional divides, particularly between supporters of Andrew Jackson (who later formed the Democratic Party) and those aligned with John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay (who later formed the Whig Party). These divisions solidified into the two-party system that dominated American politics in the mid-19th century.