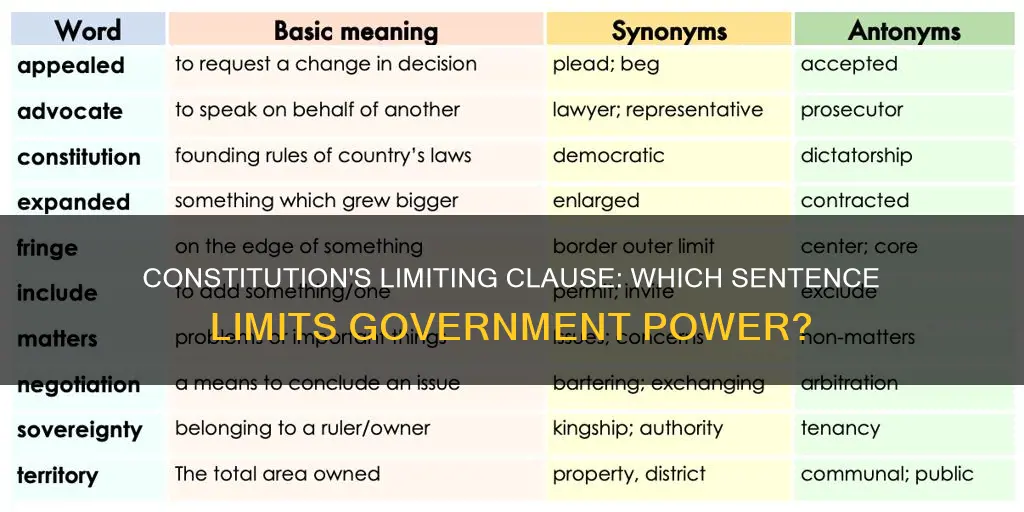

The US Constitution is a powerful document that outlines the fundamental principles of American governance. One of its key features is the system of checks and balances, designed to limit governmental power and protect individual liberties. The First Amendment, added in 1791, is a cornerstone of this, safeguarding citizens' rights to freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. However, the Tenth Amendment, also ratified in 1791, is specifically known for its role in limiting federal power. This amendment clarifies that any powers not explicitly granted to the federal government by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people, thereby maintaining a delicate balance between federal and state authority. This dynamic, known as federalism, ensures states' rights and autonomy while also promoting policy experimentation and innovation at the state level.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sentence in the US Constitution that limits the power of the government | "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." |

| Part of the Constitution | First Amendment |

| Added to the Constitution | 1791 |

| Type of Amendment | Bill of Rights |

| Purpose | Protect citizens' rights to free speech, religion, and assembly |

| Powers | Prevents the government from establishing an official religion or infringing on citizens' freedom of speech, press, and assembly |

| Powers of Congress | Make all laws which shall be necessary and proper to carry out its delegated powers |

| Powers of States | Power to tax their people and property |

| Powers Reserved for States | Regulate public welfare and morality |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

$13.1 $23.99

What You'll Learn

The First Amendment

> "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances."

Additionally, the right to assemble peaceably and petition the government is protected by the First Amendment. This right, rooted in the 1215 Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights, ensures that citizens can collectively express their grievances and seek redress from their government.

The interpretation and application of the First Amendment have evolved through various court cases, such as New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), which affirmed the importance of public debate and free speech, and Texas v. Johnson (1989), which upheld the principle that the government cannot prohibit the expression of ideas, even if they are considered offensive. These cases have shaped our understanding of the limits placed on governmental power by the First Amendment.

The US Constitution's Complex Legacy on Slavery

You may want to see also

Freedom of speech

The First Amendment to the US Constitution protects freedom of speech, religion, and the press. It also protects the freedom to assemble peacefully, to gather together, or to associate with a group of people for social, economic, political, or religious purposes, as well as the right to protest the government. The amendment was adopted in 1791, along with nine other amendments that make up the Bill of Rights, a written document protecting civil liberties under US law.

The First Amendment protects speech even when the ideas put forth are thought to be illogical, offensive, immoral, or hateful. However, this does not mean that individuals may say whatever they wish, wherever they wish. For example, universities may restrict speech that falsely defames a specific individual, constitutes a genuine threat or harassment, or is intended and likely to provoke imminent unlawful action or otherwise break the law.

The Supreme Court has interpreted "speech" and "press" broadly to cover not only talking, writing, and printing but also broadcasting, using the internet, and other forms of expression. The freedom of speech also applies to symbolic expression, such as displaying flags, burning flags, wearing armbands, burning crosses, and the like. The Supreme Court has held that restrictions on speech because of its content—that is, when the government targets the speaker's message—generally violate the First Amendment. Laws that prohibit people from criticizing a war, opposing abortion, or advocating for higher taxes are examples of unconstitutional content-based restrictions.

The First Amendment does not protect all speech, and there are certain categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection and may be restricted. These include obscenity, fraud, child pornography, speech integral to illegal conduct, speech that incites imminent lawless action, speech that violates intellectual property law, true threats, false statements of fact, and commercial speech such as advertising. Defamation that causes harm to reputation is also not protected as free speech.

The Supreme Court has also ruled that political expenditures and contributions are "speech" within the meaning of the First Amendment because they are intended to facilitate political expression by political candidates and others. However, the Court has also recognized that political expenditures and contributions could be regulated consistent with the First Amendment if the government could demonstrate a sufficiently important justification.

The US Constitution: Functions and Powers Explained

You may want to see also

Freedom of religion

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, as part of the Bill of Rights, includes the following sentence, which provides for limiting any law that would impede the freedom of religion:

> "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

This sentence, known as the Free Exercise Clause, prohibits governmental interference in religious matters and protects the freedom to practice, hold, or change one's religious beliefs without government interference. It also prevents Congress from making any law that establishes an official religion or prohibits the free exercise of religion. This clause aims to protect religious freedom and upholds the right to hold any religious beliefs, including no religion at all.

The Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment and established permissible restrictions on religious freedom. The Court's approach provides insight into the limits and reach of religious freedom under the First Amendment. The "Lemon" test, set forth in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), governs what constitutes an "establishment of religion." According to this test, the government can assist religion only if its assistance is primarily secular, does not promote or inhibit religion, and does not excessively entangle church and state.

While the right to hold religious beliefs is absolute, the freedom to act on these beliefs is not. The Supreme Court has ruled that the state's interest in protecting public health and safety can override religious practices, such as in the case of mandatory inoculation of children. Additionally, the First Amendment does not give individuals the right to impose their religious beliefs or practices on others in commercial activities or require others to conform to their religious necessities.

The Core Components of .NET Framework

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$38.04 $49.95

Freedom of the press

The history of freedom of the press in the United States dates back to the Thirteen Colonies before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. At that time, newspapers and works produced by printing presses were generally subject to a series of regulations. British authorities attempted to control the printing presses by prohibiting the publication and circulation of information they did not approve of, often levying charges of sedition and libel. One of the earliest cases concerning freedom of the press occurred in 1734 when The New York Weekly Journal publisher John Peter Zenger was acquitted in a libel case brought by British governor William Cosby.

In 1798, eleven years after the adoption of the Constitution and seven years after the ratification of the First Amendment, the governing Federalist Party attempted to stifle criticism with the Alien and Sedition Acts. According to the Sedition Act, making "false, scandalous and malicious" statements about Congress or the president was a crime. These restrictions on the press were very unpopular, leading to the party's reduction to minority status after 1801 and eventual dissolution in 1824. Thomas Jefferson, who vehemently opposed the acts, was elected president in 1800 and pardoned most of those convicted under them.

The Supreme Court has ruled that generally applicable laws do not violate the First Amendment simply because their enforcement against the press has incidental effects. However, laws targeting the press or treating different subsets of media outlets differently may violate the First Amendment. In 1936, the Supreme Court held in Grosjean v. Am. Press Co. that a tax focused exclusively on newspapers violated the freedom of the press.

While the First Amendment protects freedom of the press, it does not sanction repression of that freedom by private interests. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court ruled that when a publication involves a public figure, the plaintiff in a libel suit bears the burden of proving that the publisher knew of the inaccuracy of the statement or acted with reckless disregard for its truth.

Healthy Living: Longevity and Wellness Secrets

You may want to see also

Right to assemble

The right to assemble is a cornerstone of American democracy, protecting citizens' rights to assemble freely and express their ideas. This right is enshrined in the First Amendment to the US Constitution, which states:

> "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

This amendment, added to the Constitution in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights, is a critical component of American democracy. It ensures that citizens have the freedom to assemble and collectively promote and defend their ideas without interference from the government.

The right to assemble has a historical basis, with the Supreme Court asserting it as one of the attributes of citizenship under a free government. The Court originally conceived of the rights to petition and assemble as parts of a single right. However, over time, the right to assemble has evolved to be seen as protecting a distinct interest in holding meetings for peaceful political action.

The freedom of assembly is often used in the context of the right to protest, while the similar-sounding freedom of association is used in the context of labor rights. The Constitution of the United States guarantees both the freedom to assemble and the freedom to join an association. This right to assemble is also recognised as a human right and a civil liberty in various international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Unwritten Constitution: Presidential Actions and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The sentence in the US Constitution that limits the power of the government is the First Amendment: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

The Tenth Amendment is a "truism" and a "tautology" that specifies that any power not explicitly granted to the federal government by the Constitution is reserved for the states.

The Tenth Amendment does not formally change anything in the Constitution. However, it does emphasise that the federal government only has limited powers, and that the states have the power to regulate public welfare and morality.

The Vesting Clause is a strategy for limiting the power of Congress by requiring legislation to be agreed upon by two differently constituted chambers.