The United States Constitution grants Congress several powers, including the ability to lay and collect taxes, regulate commerce, and establish a uniform rule of naturalization. Article I of the Constitution outlines most of Congress's powers, with additional powers granted by other articles and amendments. Congress's authority to declare war and investigate the executive branch are also notable powers. The interpretation of the Constitution's delegation of powers to Congress has been a subject of debate, with the Supreme Court playing a significant role in defining the scope of Congress's authority.

Explore related products

$71.95 $71.95

What You'll Learn

The power to lay and collect taxes

The US Constitution confers upon Congress the power "to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States". This power, known as the Taxing Clause, is listed first in Article I, Section 8, indicating its importance.

The Framers of the Constitution and its ratifiers agreed that Congress must have the authority to assess, levy, and collect taxes without assistance from the states. This power was intended to address the financial shortcomings of the young nation and to ensure a stable source of revenue for the government. The power to tax implicitly includes the power to spend the revenues raised to meet the objectives and goals of the government.

The Taxing Clause grants Congress broad authority to lay and collect taxes for federal debts, common defence, and general welfare. This power has been interpreted by the Supreme Court as exhaustive and embracing every conceivable power of taxation. However, there are some limitations to Congress's taxing power, including the requirement for uniformity throughout the United States and the disallowal of taxes on exports.

Congress has used its taxing power not only for revenue collection but also for other purposes such as regulatory taxation, prohibitive taxation, and obligation taxation. Regulatory taxation involves taxing to regulate commerce, while prohibitive taxation discourages or suppresses certain types of commerce. Obligation taxation, on the other hand, encourages participation in commerce by taxing those who do not engage in it.

The Sixteenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, extended the power of taxation to include income taxes, and the Supreme Court upheld this in Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad. Despite this, the scope of Congress's taxing power has been curtailed by judicial decisions regarding the manner, objects, and subject matter of taxation.

The Constitution and Marriage: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

The power to regulate commerce

The United States Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate commerce, as outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, also known as the Commerce Clause. This clause empowers Congress to regulate interstate and foreign commerce, including commercial trade between individuals in different states and nations. The Commerce Clause has been interpreted broadly and has become a foundational component of congressional power, shaping a significant portion of legislation over the last 50 years.

The Commerce Clause has been pivotal in shaping federal laws and limiting state authority in regulating commerce. It has been invoked to address national social issues and has been central to congressional legislation in this regard. The clause's interpretation has evolved alongside the complexities of the US economy, influencing areas such as monopolies, child labour laws, minimum wage, and agricultural production limits.

While the Commerce Clause grants Congress significant regulatory power, it is not without limitations. The Supreme Court has ruled on cases that delineate the boundaries of congressional authority under the Commerce Clause. For example, in United States v. Lopez and United States v. Morrison, the Court held that gun possession and sexual violence laws were beyond Congress's ability to regulate commerce. However, in Gonzales v. Raich, the Court affirmed Congress's authority to regulate medical marijuana.

The Dormant Commerce Clause is another aspect of this power, which restricts state or local regulations even in the absence of explicit congressional legislation. This interpretation of the Commerce Clause by the Supreme Court prohibits state laws that unduly restrict interstate commerce. Cases such as Comptroller of Treasury of Md. v. Wynne and Tenn. Wine & Spirits Retailers Ass'n v. Thomas have further elucidated these principles, reinforcing the nation's economic unity and the states' role within it.

In summary, the power to regulate commerce, as delegated to Congress by the Constitution, is a critical component of US law-making. It empowers Congress to shape federal laws and address national social issues while also influencing the interpretation and application of state laws. The dynamic interpretation of the Commerce Clause has resulted in a broad scope of congressional powers, impacting various aspects of commerce and interstate trade.

The President's Unwritten Powers: Exploring Constitutional Limits

You may want to see also

The power to declare war

The US Constitution, in Article I, Section 8, Clause 11, grants Congress the power to declare war. This clause, often referred to as the War Powers Clause, states that "The Congress shall have Power ... To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water".

The interpretation and application of the Declare War Clause have evolved over time. While the US has fought several "declared wars" (the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II), modern conflicts often begin without formal declarations. This has led to debates about the necessity of formal declarations and the interpretation of the clause.

Despite the debates and controversies, the power to declare war remains a critical aspect of the US Constitution, shaping the relationship between Congress and the President in matters of national security and foreign policy.

The Great Compromise: A Constitutional Balancing Act

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The power to raise and support armies

The power to declare war and raise armies is one of the most significant authorities granted to Congress by the US Constitution. This power, outlined in Article I, Section 8, serves as a critical check and balance on the president's authority as commander-in-chief of the military. The Framers of the Constitution, drawing on their experiences during the American Revolution and the English monarchy, sought to prevent excessive control over the military by a single person or branch of government.

The historical context of the English King's power to initiate wars and maintain standing armies without adequate checks influenced the Framers' decision to vest these powers in Congress. The English Declaration of Rights of 1688, which asserted that the King could not maintain standing armies without Parliament's consent, further supported this decision. The Framers aimed to protect the liberties and well-being of citizens by ensuring that the power to raise and support armies was subject to legislative oversight.

Congress's authority to raise and support armies is not unlimited. The Constitution imposes a time restriction on appropriations for the army, stating that "no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years." This provision addresses the Framers' concerns about the potential dangers of standing armies. Additionally, the power to raise armies should not be confused with the ability to call on militias, as the Constitution does not restrict Congress from raising armies as it deems fit.

The interplay between Congress's power to raise and support armies and the president's role as commander-in-chief has been a source of ongoing debate and conflict between the legislative and executive branches. While Congress has the authority to declare war and fund military operations, the president directs military operations once a war begins, making strategic decisions about troop deployment. This division of powers allows for a balance between efficient decision-making during wartime and the necessary checks on the executive branch to prevent the misuse of military power.

In conclusion, the power to raise and support armies delegated to Congress by the Constitution is a vital aspect of the US government's system of checks and balances. It ensures that the decision to go to war and the subsequent utilisation of military resources are subject to legislative scrutiny and accountability to the people. The Framers' wisdom in distributing powers between Congress and the president continues to shape the nation's approach to warfare and the protection of citizens' liberties.

The Constitution: Elitist or Democratic?

You may want to see also

The power to propose amendments to the Constitution

Article V of the Constitution grants Congress the power to propose amendments to the Constitution. This is one of the foremost legislative functions of Congress. To propose an amendment, two-thirds of both Houses of Congress must deem it necessary. The amendment is then proposed in the form of a joint resolution, which is forwarded directly to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) for processing and publication.

The second method for proposing an amendment is for two-thirds of the state legislatures to apply to Congress, which must then call a convention for proposing amendments. This method has never been used for any of the 27 amendments to the Constitution.

Once an amendment is proposed, it is sent to the states for ratification. Ratification can be specified by Congress to be by state legislature or convention. An amendment becomes part of the Constitution as soon as it is ratified by three-quarters of the states (38 out of 50).

Congress's power to propose amendments to the Constitution has been used to grant and confirm other congressional powers. For example, the Twelfth Amendment gives Congress the power to choose the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of Electoral College votes. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments gave Congress the authority to enact legislation to enforce the rights of all citizens, regardless of race, including voting rights, due process, and equal protection under the law. The Sixteenth Amendment extended the power of taxation to include income taxes, while the Nineteenth, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments gave Congress the power to enforce the right of citizens aged 18 and above to vote.

USS Constitution: Fighting Piracy on the High Seas

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

1. To lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, 2. To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and 3. To raise and support armies.

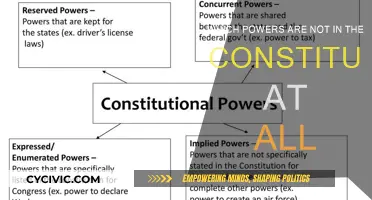

The Vesting Clause, or Article I, Section 1, vests Congress with "all legislative Powers herein granted." This has been interpreted as a delegation doctrine, making Congress the supreme lawmaker, with the authority to delegate power to other federal officials and agencies.

The Necessary and Proper Clause permits Congress to "make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States." This clause has effectively widened Congress's legislative authority, allowing for a broader interpretation of its powers.