The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, which triggered a global financial meltdown, has sparked intense debate over which political party bears the brunt of the blame. Critics often point to both Democratic and Republican policies as contributing factors, with arguments focusing on deregulation, government housing policies, and the role of financial institutions. While some blame Democratic initiatives like the Community Reinvestment Act for encouraging risky lending, others argue that Republican-backed deregulation and lax oversight under the Bush administration enabled predatory practices. Ultimately, the crisis was a complex interplay of factors, making it challenging to assign fault solely to one political party.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party Involvement | Both Democratic and Republican parties have been criticized, but no single party was solely at fault. The crisis was a result of bipartisan policies and actions. |

| Key Policies | - Community Reinvestment Act (CRA): Encouraged lending to low-income borrowers, though its direct role is debated. - Deregulation: Both parties supported policies reducing oversight of financial institutions. |

| Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) | Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, backed by implicit government support, played a significant role in purchasing and securitizing subprime mortgages. |

| Regulatory Failures | Regulators under both Democratic and Republican administrations failed to address risky lending practices and the growing housing bubble. |

| Wall Street Influence | Both parties received campaign contributions from financial institutions, leading to lax regulation and oversight. |

| Public Perception | Republicans are often criticized for deregulation, while Democrats are criticized for pushing affordable housing policies. However, both parties share blame in public opinion. |

| Historical Context | The crisis was decades in the making, involving multiple administrations and Congresses, making it difficult to attribute fault to a single party. |

| Legal and Financial Consequences | No single party faced legal consequences, but both faced political backlash. The Dodd-Frank Act (2010) under Obama aimed to prevent future crises. |

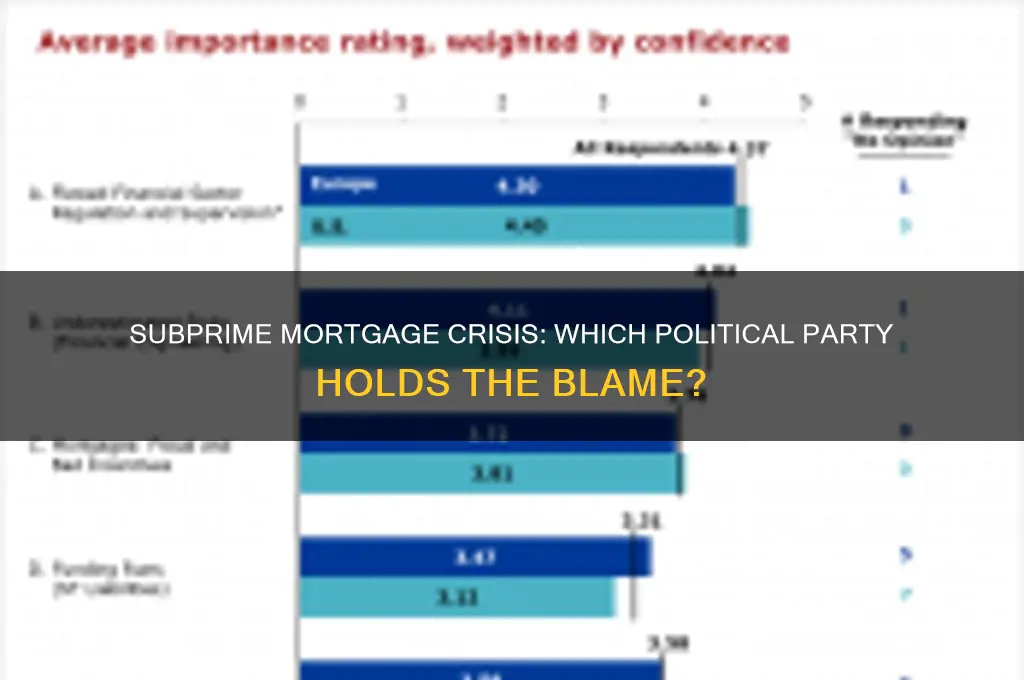

| Expert Consensus | Most economists agree the crisis was caused by a combination of factors, including government policies, private sector actions, and global economic conditions, not solely partisan politics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Deregulation Policies: Republican-led efforts to reduce financial regulations enabled risky lending practices

- Democratic Housing Goals: Clinton-era policies pushed homeownership, increasing demand for subprime loans

- Wall Street Influence: Both parties' ties to financial lobbyists weakened oversight and accountability

- Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac: Government-backed entities fueled subprime lending under bipartisan support

- Regulatory Failures: Bush administration's SEC and Fed ignored warning signs of market collapse

Deregulation Policies: Republican-led efforts to reduce financial regulations enabled risky lending practices

The subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 was fueled by a toxic mix of greed, lax oversight, and deregulation. At the heart of this deregulation were Republican-led policies that dismantled safeguards designed to prevent predatory lending and ensure financial stability. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, championed by Republican lawmakers, repealed key provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act, allowing commercial and investment banks to merge. This consolidation incentivized riskier lending practices as banks sought higher profits through complex financial instruments tied to subprime mortgages.

Consider the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), often misidentified as a primary driver of the crisis. While the CRA encouraged lending in underserved communities, it did not mandate subprime loans. Instead, deregulation under Republican administrations, such as the Bush-era SEC’s decision to relax capital requirements for investment banks, enabled these institutions to leverage themselves excessively. For instance, by 2007, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were operating with leverage ratios exceeding 30:1, meaning they held just $1 in capital for every $30 in debt. This fragility amplified the impact of defaults when the housing bubble burst.

The role of government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac further complicates the narrative. While these entities did purchase subprime loans, their actions were not driven by deregulation alone. However, Republican efforts to weaken oversight of GSEs, such as blocking reforms proposed in the early 2000s, allowed them to operate with minimal scrutiny. Between 2005 and 2007, Fannie and Freddie acquired over $400 billion in subprime and Alt-A mortgages, contributing to the crisis. This lack of accountability was a direct result of regulatory rollbacks.

To understand the impact of these policies, examine the timeline: the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999, followed by the SEC’s 2004 decision to allow investment banks to increase their debt-to-equity ratios, created an environment ripe for abuse. Subprime lending surged from 8% of all mortgages in 2001 to 20% by 2006. While Democrats also played a role in enabling the crisis, the deregulatory agenda pushed by Republicans was a critical factor. For example, Phil Gramm, a Republican senator and co-author of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, famously dismissed concerns about the economy in 2008, calling it a “mental recession.” Such attitudes reflected a broader ideological commitment to reducing financial oversight.

In practical terms, these deregulation policies had real-world consequences. Homebuyers with poor credit were lured into adjustable-rate mortgages with low initial payments that later ballooned, leading to widespread defaults. The lesson here is clear: deregulation without robust safeguards invites systemic risk. Policymakers must balance innovation with accountability to prevent future crises. While no single party bears sole responsibility, the Republican-led push to dismantle financial regulations played a significant role in enabling the reckless lending practices that precipitated the subprime mortgage crisis.

Discover Your Political Party: A Guide to Finding Your Ideological Home

You may want to see also

Democratic Housing Goals: Clinton-era policies pushed homeownership, increasing demand for subprime loans

The Clinton administration's ambitious housing goals, particularly those outlined in the National Homeownership Strategy of 1995, played a pivotal role in shaping the subprime mortgage market. This strategy aimed to increase homeownership rates, especially among low-income and minority households, by encouraging lenders to relax underwriting standards and expand access to credit. While the initiative was well-intentioned, it inadvertently fueled the demand for subprime loans, setting the stage for the crisis that would unfold a decade later.

One of the key mechanisms employed to achieve these goals was the expansion of the Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These entities were tasked with purchasing and securitizing mortgages, including those issued to borrowers with lower credit scores. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) established affordable housing goals, requiring the GSEs to allocate a significant portion of their portfolios to loans for low- and moderate-income borrowers. Between 1996 and 2005, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchased over $2 trillion in subprime and other non-traditional mortgages, effectively mainstreaming these riskier products.

Critics argue that this policy framework created a moral hazard, as lenders were incentivized to originate subprime loans without adequately assessing the long-term risks. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), another Clinton-era policy, further exacerbated this trend by encouraging banks to lend in underserved communities, often with less stringent credit requirements. While the CRA itself did not mandate subprime lending, it contributed to a regulatory environment that prioritized volume over prudence. For instance, between 2004 and 2006, CRA-related loans accounted for a disproportionate share of high-risk mortgages, according to a 2010 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

However, it is essential to approach this narrative with nuance. The Democratic housing goals were not the sole driver of the subprime crisis; they operated within a broader context of financial deregulation, Wall Street greed, and global economic factors. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, for example, repealed key provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act, allowing commercial and investment banks to merge and engage in riskier activities. Similarly, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) decision to relax capital requirements for large investment banks in 2004 enabled firms like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers to leverage their balance sheets to unprecedented levels.

In retrospect, the Clinton-era policies highlight the unintended consequences of well-meaning initiatives. While expanding homeownership opportunities was a noble goal, the lack of robust oversight and risk management mechanisms turned a policy success into a systemic vulnerability. Policymakers and regulators must heed this lesson: promoting access to credit is essential, but it must be balanced with safeguards to prevent market excesses. Practical steps for future housing policies could include stress-testing loan portfolios, implementing countercyclical capital buffers, and ensuring transparency in mortgage securitization. By learning from the past, we can strive to create a more equitable and stable housing market.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Kentucky: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Wall Street Influence: Both parties' ties to financial lobbyists weakened oversight and accountability

The subprime mortgage crisis, which precipitated the 2008 financial collapse, was not the handiwork of a single political party. Instead, it was the culmination of decades of bipartisan deregulation, lax oversight, and deep-seated ties to Wall Street lobbyists. Both Democrats and Republicans fostered an environment where financial institutions operated with impunity, prioritizing short-term gains over long-term stability. This shared culpability underscores a systemic issue: the corrosive influence of money in politics, which eroded accountability and enabled the crisis.

Consider the legislative landscape leading up to 2008. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, championed by Republicans, dismantled the Glass-Steagall Act, allowing commercial and investment banks to merge. This deregulation, coupled with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, created a regulatory vacuum for complex financial instruments like mortgage-backed securities. Simultaneously, Democrats, under the Clinton administration, pushed for expanded homeownership through policies like the Affordable Housing Goals, which incentivized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase riskier loans. Both parties, in their pursuit of economic growth and political favor, laid the groundwork for the crisis.

Lobbying played a pivotal role in this narrative. Between 1998 and 2008, the financial sector spent over $5 billion on lobbying efforts, targeting both sides of the aisle. For instance, the American Bankers Association and the Securities Industry Association successfully watered down attempts to regulate derivatives and subprime lending. Campaign contributions further cemented these ties: in the 2008 election cycle alone, the financial industry donated $475 million to federal candidates, with Democrats and Republicans receiving nearly equal shares. This quid pro quo dynamic ensured that neither party had the political will to challenge Wall Street’s excesses.

The consequences of this bipartisan failure were stark. Regulatory agencies like the SEC and the Federal Reserve, staffed with industry-friendly appointees, turned a blind eye to predatory lending practices and risky securitization. The result? Millions of Americans lost their homes, while financial institutions were bailed out with taxpayer money. This crisis exposed the fragility of a system where political parties are beholden to corporate interests rather than the public good.

To break this cycle, structural reforms are essential. First, implement stricter campaign finance laws to limit the influence of financial lobbyists. Second, strengthen regulatory agencies with independent funding and leadership insulated from political pressure. Finally, hold lawmakers accountable by mandating transparency in their interactions with industry representatives. The subprime mortgage crisis was not a partisan failure but a systemic one—a reminder that without meaningful oversight, Wall Street’s power will always outstrip Main Street’s interests.

Exploring William Shatner's Political Party Affiliation: A Surprising Revelation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.82 $27.99

Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac: Government-backed entities fueled subprime lending under bipartisan support

The subprime mortgage crisis, which precipitated the 2008 financial collapse, often sparks debates about which political party bore the brunt of the blame. However, a closer examination reveals that government-backed entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac played a pivotal role in fueling subprime lending, operating under bipartisan support that transcended party lines. These institutions, chartered by Congress, were designed to expand homeownership but instead became catalysts for risky lending practices that ultimately destabilized the housing market.

Consider the mechanics of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s involvement. Their mandate to purchase and securitize mortgages created a secondary market that incentivized lenders to originate loans, including those to borrowers with lower creditworthiness. By guaranteeing these loans, they effectively reduced lenders’ risk, encouraging the proliferation of subprime mortgages. For instance, between 2004 and 2006, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchased over $2 trillion in mortgages, with a significant portion classified as subprime or Alt-A loans. This massive influx of capital into the subprime market was not a partisan initiative but a policy supported by both Democratic and Republican administrations, each seeking to boost homeownership rates for political and economic gains.

A comparative analysis of legislative actions further underscores the bipartisan nature of this support. The Housing and Community Development Act of 1992, signed by President George H.W. Bush, mandated that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac allocate 30% of their mortgage purchases to low-income borrowers, a quota later increased to 50% under the Clinton administration. Similarly, the Bush-era American Dream Downpayment Act of 2003 and the Clinton-era efforts to expand the Community Reinvestment Act both aimed to increase homeownership among underserved populations, indirectly pressuring these entities to lower lending standards. These policies, while well-intentioned, created a regulatory environment where subprime lending thrived, insulated by the implicit government guarantee of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The takeaway is clear: assigning blame for the subprime mortgage crisis solely to one political party oversimplifies a complex issue. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, operating under bipartisan policies, were central to the crisis. Their role highlights the dangers of government intervention in markets without adequate oversight and risk management. For policymakers and citizens alike, this serves as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of pursuing social goals through financial mechanisms. To prevent future crises, reforms must focus on aligning incentives, enhancing transparency, and ensuring that government-backed entities prioritize long-term stability over short-term political gains.

Mississippi's Political Landscape: Which Party Dominates the Magnolia State?

You may want to see also

Regulatory Failures: Bush administration's SEC and Fed ignored warning signs of market collapse

The 2008 financial crisis, rooted in the subprime mortgage debacle, exposed critical regulatory failures during the Bush administration. Both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Reserve (Fed) overlooked glaring warning signs, contributing significantly to the market’s collapse. While multiple factors played a role, the inaction of these key regulatory bodies under Bush’s watch stands out as a pivotal failure.

Consider the SEC’s role in overseeing investment banks and ensuring market transparency. During the early 2000s, investment banks like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns were packaging subprime mortgages into complex financial instruments, such as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and selling them to investors. Despite clear evidence of lax underwriting standards and rising delinquency rates, the SEC failed to enforce stricter regulations or investigate these practices. For instance, the SEC’s Division of Trading and Markets allowed investment banks to operate with dangerously high leverage ratios, sometimes exceeding 30:1. This lack of oversight enabled these institutions to amplify risks across the financial system, setting the stage for their eventual collapse.

Simultaneously, the Fed, under Chairman Alan Greenspan and later Ben Bernanke, ignored systemic risks in the housing market. Greenspan’s ideology of minimal intervention and his belief in self-correcting markets led the Fed to maintain low interest rates from 2001 to 2004, fueling a housing bubble. Even as home prices soared and subprime lending surged, the Fed failed to use its authority under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) to curb predatory lending practices. Bernanke, though more proactive in addressing the crisis once it began, initially downplayed the risks, famously referring to the housing slowdown as a "contained" problem in 2007. This regulatory inertia allowed the bubble to grow unchecked, ensuring its eventual burst would be catastrophic.

The takeaway is clear: the Bush administration’s SEC and Fed prioritized deregulation and market optimism over prudent oversight. Their failure to act on early warnings—such as rising foreclosures, fraudulent lending practices, and excessive risk-taking by financial institutions—exacerbated the crisis. While not solely to blame, their regulatory neglect was a critical factor in the subprime mortgage meltdown. To prevent future crises, regulators must adopt a proactive, data-driven approach, prioritizing systemic stability over ideological adherence to laissez-faire economics.

Exploring the Political Parties of the 1780s: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The subprime mortgage crisis was not the fault of a single political party. Both Democrats and Republicans contributed to policies and regulatory decisions that led to the crisis, though there is debate over the extent of each party’s responsibility.

Some argue that Democratic policies, such as the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and affordable housing goals, encouraged risky lending. However, studies show that the CRA was not a primary driver of the crisis, and many subprime loans were made by institutions not subject to the CRA.

Republican policies, including deregulation and the promotion of homeownership through government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, played a role. Critics also point to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, which repealed parts of the Glass-Steagall Act, as a contributing factor.

GSEs, which were under both Democratic and Republican influence, contributed to the crisis by purchasing and securitizing subprime mortgages. However, private lenders and investment banks also played a significant role in originating and bundling risky loans.

Both Wall Street and politicians share responsibility. Financial institutions engaged in predatory lending and created complex financial instruments, while politicians failed to implement adequate regulations and oversight. The crisis was a result of systemic failures across both sectors.