The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude (except as punishment for a crime), was a pivotal moment in American history. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, with overwhelming support from the Republican Party, which had made the abolition of slavery a central tenet of its platform. At the time, the Republican Party held a majority in both chambers of Congress, and their votes were crucial in securing the amendment's passage. While some Democrats also supported the amendment, the majority of Democratic lawmakers opposed it, reflecting the party's divided stance on the issue of slavery during the Civil War era. The 13th Amendment was ultimately ratified on December 6, 1865, marking a significant step toward racial equality and the end of a dark chapter in American history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Amendment | 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution |

| Purpose | Abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime |

| Year Passed by Congress | 1864 (House) and 1865 (Senate) |

| Year Ratified | December 6, 1865 |

| Political Party Supporting (House) | Republican Party (overwhelming majority) |

| Political Party Supporting (Senate) | Republican Party (unanimous support) |

| Democratic Party Stance (House) | Majority opposed |

| Democratic Party Stance (Senate) | Majority opposed |

| Key Republican Figures | Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens |

| Key Democratic Opposition | Fernando Wood, George H. Pendleton |

| Historical Context | Passed during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era |

| Impact | Formally ended slavery in the United States |

| Modern Relevance | Foundation for civil rights legislation and anti-slavery efforts worldwide |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Republican Role in Passing the 13th Amendment

The 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, was a pivotal moment in American history. While both political parties played a role in its passage, the Republican Party’s leadership and strategic efforts were instrumental in securing its ratification. A closer look at the legislative process reveals how Republicans, driven by their anti-slavery platform, navigated political divides to achieve this landmark victory.

Step 1: Mobilizing Congressional Support

Republicans, led by figures like Representative James Ashley and Senator Lyman Trumbull, spearheaded the amendment’s introduction in Congress. In January 1864, Ashley proposed the resolution in the House, while Trumbull guided it through the Senate. Despite initial resistance from Democrats, who largely opposed the measure, Republicans leveraged their majority in both chambers to advance the amendment. The House passed it in June 1864, with 89% of Republicans voting in favor compared to only 23% of Democrats. This stark partisan divide underscores the Republican Party’s commitment to abolition.

Caution: Overcoming Internal Divisions

While Republicans were the driving force, they were not monolithic in their support. Some moderate Republicans feared the amendment would alienate border states or complicate the war effort. President Abraham Lincoln himself initially focused on gradual, compensated emancipation. However, Lincoln’s evolution on the issue, coupled with pressure from radical Republicans like Charles Sumner, solidified the party’s resolve. By 1864, Lincoln made the 13th Amendment a central plank of his reelection campaign, uniting the party behind its passage.

Step 2: Securing State Ratification

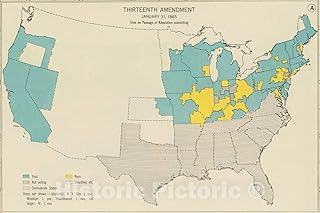

After Congress passed the amendment, Republicans turned their attention to state legislatures. Ratification required approval from three-fourths of the states, a daunting task given Democratic opposition. Republicans strategically targeted states with upcoming elections, campaigning on the amendment’s moral and political imperative. By December 1865, enough states had ratified the amendment, with Republican-dominated legislatures in the North and West providing the bulk of the votes. Notably, not a single Southern state initially ratified it, highlighting the regional and partisan split.

Takeaway: A Legacy of Leadership

The Republican Party’s role in passing the 13th Amendment was not just a legislative achievement but a moral triumph. By championing abolition, Republicans fulfilled their founding principles and reshaped the nation’s future. While the fight for racial equality continued long after 1865, the 13th Amendment stands as a testament to the party’s leadership in dismantling the institution of slavery. Understanding this history offers valuable insights into the power of political will and the enduring impact of legislative action.

Media Control: Political Influence or Independent Journalism?

You may want to see also

Democratic Opposition to the 13th Amendment

The Democratic Party's opposition to the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, was a pivotal yet often overlooked chapter in American political history. While the Republican Party is widely credited with championing the amendment, Democratic resistance played a significant role in shaping its passage and aftermath. Understanding this opposition requires examining the party’s regional divisions, ideological stances, and the political calculus of the time.

Southern Democrats, who formed the backbone of the Confederacy, were staunchly opposed to the 13th Amendment. For them, slavery was not merely an economic institution but a cornerstone of their social and political order. The amendment threatened to dismantle this foundation, stripping them of both labor and perceived racial hierarchy. Their resistance was visceral and uncompromising, with many viewing it as an attack on states' rights and Southern identity. This opposition was so fierce that not a single Democratic representative from the South voted in favor of the amendment in the House.

Northern Democrats, however, presented a more nuanced opposition. While some genuinely supported slavery, others were motivated by political pragmatism. Many feared alienating Southern constituents or disrupting party unity. Others opposed the amendment on constitutional grounds, arguing that it overstepped federal authority. This ideological divide within the party highlights the complexity of Democratic resistance, which was not monolithic but rather a reflection of regional and personal interests.

The Democratic Party’s opposition had tangible consequences for the amendment’s passage. In the House, only a handful of Northern Democrats voted in favor, forcing Republicans to rely almost exclusively on their own party members. This partisan divide underscored the growing rift between the two parties over the issue of slavery and foreshadowed the realignment of American politics in the post-Civil War era. Despite Democratic resistance, the amendment ultimately passed, but the party’s opposition delayed its ratification and influenced its implementation.

Understanding Democratic opposition to the 13th Amendment offers critical insights into the complexities of political change. It reminds us that progress is often met with resistance, even within the very institutions tasked with enacting it. For historians and educators, this chapter serves as a cautionary tale about the enduring power of regional and ideological divides. For modern readers, it underscores the importance of examining the motivations behind political actions, even when they seem morally indefensible in hindsight. By studying this opposition, we gain a more nuanced understanding of the forces that shape history and the ongoing struggle for equality.

MSNBC's Political Leanings: Uncovering the Network's Ideological Stance

You may want to see also

Key Figures in the Amendment’s Approval

The 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, was a pivotal moment in American history. Its passage required the concerted efforts of key figures who navigated the complex political landscape of the Civil War era. Among these figures, President Abraham Lincoln stands out as the driving force behind the amendment’s approval. Lincoln’s unwavering commitment to ending slavery, despite political opposition, was instrumental in rallying support. His issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 laid the groundwork for the amendment, signaling a shift in the war’s purpose from merely preserving the Union to eradicating slavery. Lincoln’s strategic timing in pushing for the amendment’s passage during the lame-duck session of Congress in 1865 ensured its success, as he leveraged the absence of lame-duck Democrats who opposed it.

While Lincoln’s leadership was crucial, the role of congressional figures cannot be overlooked. Representative James M. Ashley, a Republican from Ohio, introduced the resolution for the 13th Amendment in December 1863. Ashley’s persistence in advocating for the amendment, despite initial resistance, was vital in keeping it on the legislative agenda. Similarly, Senator Charles Sumner, a Radical Republican from Massachusetts, played a key role in shaping the amendment’s language and ensuring its passage in the Senate. Sumner’s lifelong dedication to abolitionism and his collaboration with Frederick Douglass, a prominent Black activist, bridged the gap between political action and grassroots advocacy.

The Democratic Party’s stance on the 13th Amendment was largely one of opposition, particularly among its Southern and border state members. However, the amendment’s passage required a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, necessitating some Democratic support. Key figures like Representative Samuel Shellabarger of Ohio, a War Democrat, broke party ranks to vote in favor of the amendment. Their willingness to defy their party’s majority position highlights the moral and political complexities of the time. These Democrats, often referred to as “conservative abolitionists,” prioritized the end of slavery over party loyalty, demonstrating that individual conviction could transcend partisan divides.

Beyond politicians, the influence of activists and public intellectuals was critical in shaping public opinion and pressuring lawmakers. Frederick Douglass, whose eloquence and moral authority made him a leading voice in the abolitionist movement, met with Lincoln at the White House to discuss the amendment’s importance. Douglass’s advocacy helped galvanize public support, particularly among Northern voters. Similarly, women like Lydia Maria Child and Harriet Beecher Stowe used their writing to expose the horrors of slavery and build a moral case for abolition. Their efforts, combined with those of political leaders, created a cultural and political climate conducive to the amendment’s approval.

In conclusion, the approval of the 13th Amendment was the result of a multifaceted effort involving political strategists, legislative champions, dissenting party members, and grassroots activists. Each of these key figures played a unique role in overcoming the obstacles to abolition. Their collective actions remind us that monumental change often requires the convergence of leadership, moral courage, and public engagement. Understanding their contributions not only sheds light on the past but also offers lessons for addressing contemporary struggles for justice and equality.

Why Progressives Broke Away: The Birth of a New Political Party

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Congressional Vote Breakdown by Party

The 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, was passed by Congress in 1864 and ratified in 1865. A breakdown of the congressional vote reveals significant partisan divides that reflect the political landscape of the time. In the House of Representatives, the amendment passed with 119 Republican votes in favor and only 8 against, while Democrats were split, with 56 voting against and 16 in favor. This stark contrast highlights the Republican Party’s near-unanimous support for abolition, driven by their anti-slavery platform, versus the Democratic Party’s internal divisions, particularly among Southern Democrats who staunchly opposed the measure.

In the Senate, the vote followed a similar pattern. Republicans, who held a majority, voted overwhelmingly in favor, with 30 supporting and only 2 opposing the amendment. Democrats, however, were more unified in opposition, with 12 voting against and only 3 in favor. This breakdown underscores the role of party ideology in shaping the vote, as Republicans championed abolition as a central tenet of their party, while many Democrats, particularly those from Southern states, resisted the erosion of the slave-based economy.

Analyzing these numbers reveals the 13th Amendment as a partisan issue rather than a universally supported moral imperative. The Republican Party’s near-unanimous backing was a strategic and ideological choice, solidifying their stance as the party of freedom and progress. Conversely, the Democratic Party’s divided vote reflects the complexities of regional interests and the lingering influence of pro-slavery sentiments within their ranks. This partisan split would have lasting implications for the political realignment of the post-Civil War era.

For those studying legislative history or political science, this vote breakdown serves as a practical example of how party affiliation can dictate outcomes on transformative issues. To further explore this dynamic, examine roll call votes from both chambers, available in congressional records, to identify individual lawmakers’ stances. Additionally, compare these votes with party platforms from the 1860s to understand the ideological underpinnings of each party’s position. This approach provides a nuanced understanding of how political parties shape—and are shaped by—landmark legislation.

Finally, the 13th Amendment’s passage offers a cautionary tale about the limitations of bipartisanship in the face of deeply entrenched interests. While the amendment ultimately succeeded, its partisan nature delayed its passage and foreshadowed ongoing struggles over civil rights. For modern policymakers, this history underscores the importance of building coalitions that transcend party lines when addressing systemic injustices. By studying this vote breakdown, we gain insights into the mechanics of legislative change and the enduring impact of political polarization.

No Parties, New Politics: Reimagining American Democracy Without Divisions

You may want to see also

Impact of the 1864 Election on the Vote

The 1864 presidential election, occurring amidst the Civil War, played a pivotal role in shaping the political landscape for the passage of the 13th Amendment. Abraham Lincoln, running as the National Union Party candidate (a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats), faced off against George B. McClellan, the Democratic nominee. Lincoln’s reelection was critical because it ensured continued Republican control of the executive branch, a party staunchly committed to abolition. Had McClellan, who advocated for a negotiated peace with the Confederacy, won, the momentum for abolition might have stalled, as many Democrats were skeptical of or outright opposed to the 13th Amendment.

Analyzing the election’s impact reveals a strategic shift in Republican efforts. Lincoln’s victory provided the political capital needed to push the amendment through Congress. The Republican Party, which had already passed the amendment in the Senate in April 1864, intensified its campaign in the House. Lincoln himself lobbied wavering representatives, offering political favors and even appointing pro-amendment Democrats to government posts. This aggressive strategy was only possible because the election had solidified Republican dominance and Lincoln’s leadership.

Comparatively, the Democratic Party’s stance on the 13th Amendment was far less unified. While some War Democrats supported abolition, the party’s platform in 1864 emphasized states’ rights and opposition to what they saw as Republican overreach. McClellan’s defeat weakened the Democratic Party’s influence in Congress, making it easier for Republicans to secure the two-thirds majority required for passage. Without Lincoln’s reelection, the amendment’s fate might have hinged on protracted negotiations or even failed entirely.

Practically, the 1864 election served as a referendum on emancipation. Lincoln’s win demonstrated public support for ending slavery, emboldening Republicans to act decisively. The amendment was passed by the House in January 1865, just months after the election, and ratified later that year. This timeline underscores how the election’s outcome directly accelerated the abolition process. For historians and political analysts, this case study highlights the interplay between electoral politics and constitutional change, offering a blueprint for understanding how elections can shape legislative outcomes.

In conclusion, the 1864 election was not merely a contest between Lincoln and McClellan but a turning point in the fight for abolition. It provided the political mandate and momentum necessary for the 13th Amendment’s passage, illustrating how electoral victories can translate into transformative policy changes. This historical moment remains a testament to the power of elections in shaping the course of history.

Which Political Party Does Donald Trump Currently Align With?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party overwhelmingly supported and voted for the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude.

Most Democrats opposed the 13th Amendment, with only a small fraction voting in favor. The majority of support came from Republicans.

Yes, while Republicans largely supported it, some Democrats from border states voted in favor, and a few Republicans opposed it, though the overall trend followed party lines.