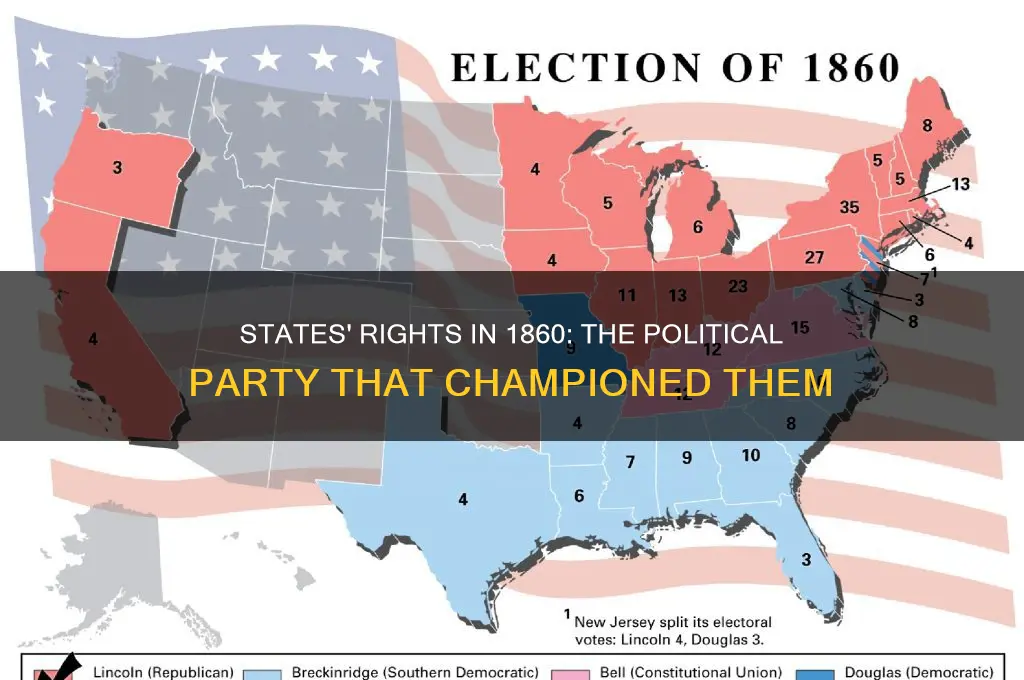

In 1860, the Democratic Party was the primary political party that strongly supported states' rights, a principle rooted in the belief that individual states should retain sovereignty and autonomy over federal authority. This stance was particularly prominent among Southern Democrats, who viewed states' rights as essential to protecting their agrarian economy, slavery, and regional interests against perceived Northern dominance and federal overreach. The party's platform during the 1860 presidential election, which saw the nomination of John C. Breckinridge as the Southern Democratic candidate, explicitly emphasized the right of states to secede from the Union if they deemed it necessary, reflecting the deep ideological divide that ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Democratic Party |

| Year | 1860 |

| Core Belief | Strong support for states' rights and limited federal government |

| Key Issue | Opposition to federal restrictions on slavery in new territories |

| Platform | Emphasized state sovereignty and the right to decide on slavery locally |

| Prominent Figures | John C. Breckinridge (1860 Democratic candidate), Jefferson Davis |

| Geographic Support | Primarily in the Southern United States |

| Outcome | Split in the Democratic Party led to the formation of the Confederate States of America |

| Historical Context | Supported secession as a means to protect states' rights and slavery |

| Legacy | Associated with the Confederate cause during the American Civil War |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Southern Democrats' Advocacy

In 1860, the Southern Democrats staunchly advocated for states' rights, a principle deeply intertwined with their defense of slavery and regional autonomy. This advocacy was not merely a political stance but a cornerstone of their identity, shaping their response to the growing sectional tensions in the United States. By framing states' rights as a bulwark against federal overreach, Southern Democrats sought to protect their economic and social systems, which were inextricably linked to enslaved labor. Their arguments often revolved around the Tenth Amendment, asserting that powers not granted to the federal government were reserved for the states or the people.

To understand their advocacy, consider the Southern Democrats' strategy in the 1860 presidential election. They vehemently opposed the Republican Party, which sought to restrict the expansion of slavery into new territories. Southern Democrats argued that such restrictions violated states' rights, as they believed each state should have the autonomy to decide on slavery within its borders. This position was not just theoretical; it was a practical defense of their way of life. For instance, the Democratic Party’s split into Northern and Southern factions in 1860 highlighted the irreconcilable differences over states' rights and slavery, with Southern Democrats ultimately supporting John C. Breckinridge, who championed their cause.

A key example of Southern Democrats' advocacy is their reaction to federal legislation like the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision. They lauded these measures as affirmations of states' rights, ensuring that Southern states could enforce their property rights in enslaved individuals even in free states. Conversely, they vehemently opposed laws like the Missouri Compromise and the Wilmot Proviso, which they viewed as federal encroachment on state sovereignty. This selective interpretation of states' rights reveals their primary goal: preserving slavery and the economic power it conferred upon the South.

Practically, Southern Democrats' advocacy for states' rights had far-reaching implications. It influenced their secessionist movement, culminating in the formation of the Confederate States of America. By framing secession as an exercise of states' rights, they justified their break from the Union, even though such an act was unprecedented and controversial. This narrative was not just for internal consumption; it was also a tool to garner international support, particularly from European powers that might sympathize with the principle of self-determination.

In conclusion, Southern Democrats' advocacy for states' rights in 1860 was a calculated and multifaceted strategy to protect slavery and regional autonomy. Their arguments, rooted in constitutional interpretation and economic self-interest, shaped the political landscape of the era. While their stance ultimately led to the Civil War, it remains a critical case study in the tension between federal authority and state sovereignty. Understanding this advocacy provides insight into the complexities of American political history and the enduring debates over the balance of power in the United States.

How Political Parties Shape Policy: Strategies, Power, and Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Constitutional Interpretation

The 1860 presidential election exposed a deep rift in American politics, with the issue of states' rights at its core. The Democratic Party, fractured by regional divisions, emerged as the primary advocate for states' rights, particularly in the South. Their platform emphasized the sovereignty of individual states and the right to secede from the Union, a position rooted in a specific interpretation of the Constitution.

Southern Democrats, fearing federal encroachment on slavery, championed a strict constructionist view of the Constitution. They argued that the document granted limited powers to the federal government, with all remaining authority reserved for the states. This interpretation, often referred to as "states' rights," became a rallying cry for those seeking to protect the institution of slavery and resist federal intervention.

This interpretation, however, was not universally accepted. Republicans, led by Abraham Lincoln, held a different view. They believed in a more expansive federal government with the authority to regulate certain aspects of national life, including the morality of slavery. Lincoln famously argued that the Declaration of Independence's principle of equality applied to all Americans, and that the federal government had a role in ensuring those rights.

This clash of interpretations highlights the inherent flexibility and ambiguity of the Constitution. The document, while providing a framework for governance, leaves room for differing readings, allowing for competing political ideologies to claim legitimacy.

Understanding these competing interpretations is crucial for comprehending the political landscape of 1860. The Democratic Party's embrace of states' rights was not merely a political tactic but a reflection of a deeply held belief in the primacy of state sovereignty. This belief, rooted in a particular reading of the Constitution, ultimately contributed to the secession of Southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War.

Understanding the Structure and Organization of Political Parties in AP Gov

You may want to see also

Nullification Doctrine

The Nullification Doctrine, a cornerstone of states' rights advocacy in the early 19th century, posits that individual states possess the authority to invalidate, or "nullify," federal laws they deem unconstitutional. This principle, championed by figures like John C. Calhoun, emerged as a direct challenge to federal supremacy and became a rallying cry for states seeking to protect their autonomy. By 1860, the doctrine had become closely associated with the Southern states, particularly those in the Democratic Party, which increasingly viewed nullification as a means to resist federal interference with slavery.

To understand the Nullification Doctrine’s appeal in 1860, consider its application during the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833. South Carolina, arguing that federal tariffs unfairly burdened its economy, declared the tariffs null and void within its borders. This act of defiance, though ultimately resolved through compromise, set a precedent for states to challenge federal authority. By 1860, Southern Democrats embraced this precedent as a tool to safeguard slavery, fearing that federal laws restricting its expansion would undermine their economic and social systems. The doctrine thus became a political weapon, not merely a theoretical principle.

Implementing nullification, however, was fraught with risks. It required a state to openly defy federal law, potentially triggering a constitutional crisis. For instance, if a state nullified a federal law and the federal government enforced it anyway, the result could be a dangerous standoff. This was evident in the lead-up to the Civil War, when Southern states threatened to nullify federal laws they perceived as anti-slavery. The practical challenge lay in determining which entity—the state or the federal government—held the ultimate authority to interpret the Constitution.

Critics of the Nullification Doctrine argue that it undermines the very foundation of a unified nation. If every state could nullify laws it disliked, the federal government’s ability to function would be severely compromised. Proponents, however, contend that it serves as a vital check on federal overreach, ensuring that states retain the power to protect their interests. By 1860, this debate had become deeply polarized, with the Democratic Party, particularly its Southern faction, staunchly defending nullification as essential to states' rights.

In practice, the Nullification Doctrine was less a legal mechanism than a political strategy. It relied on collective state action and public support to be effective. For example, if multiple states nullified a federal law simultaneously, the federal government might be forced to reconsider its position. However, this approach required unity among states, which was increasingly difficult to achieve by 1860 as the nation divided over slavery. The doctrine’s limitations became evident as it failed to prevent the secession crisis, highlighting its inadequacy as a long-term solution to constitutional disputes.

In conclusion, the Nullification Doctrine represented a bold assertion of states' rights in 1860, particularly within the Democratic Party’s Southern wing. While it offered a theoretical framework for resisting federal authority, its practical application was fraught with challenges and risks. As a political tool, it underscored the deepening divide between states' rights advocates and proponents of federal supremacy, ultimately contributing to the tensions that led to the Civil War. Understanding its role in 1860 provides critical insight into the complexities of American political thought during this pivotal era.

Exploring the Role and Impact of Third Political Parties in Democracy

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Secession Movement

The 1860 presidential election exposed deep fractures in American politics, with the issue of states' rights at the forefront. The Democratic Party, traditionally a champion of states' rights, found itself divided over the question of secession. Southern Democrats, fearing that the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party would threaten their way of life, particularly slavery, began to advocate for secession as a means to preserve their autonomy. This movement was not merely a political strategy but a reflection of the South's growing conviction that states had the right to withdraw from the Union if they deemed it necessary.

To understand the secession movement, consider the steps Southern leaders took to justify their actions. First, they relied on the doctrine of states' rights, arguing that the Constitution was a compact among sovereign states, and thus, any state could nullify federal laws or secede if those laws infringed on their rights. Second, they framed secession as a defensive measure, portraying the North as an aggressor intent on destroying the Southern economy and social structure. Third, they mobilized public opinion through newspapers, speeches, and local conventions, creating a sense of unity and urgency. These steps were not spontaneous but part of a calculated effort to legitimize secession in the eyes of both Southerners and the international community.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the secession movement and the stance of the Republican Party. While Southern Democrats championed states' rights as a justification for secession, Republicans viewed such actions as a violation of the Union’s integrity. Lincoln, in his inaugural address, argued that the Union was perpetual and indivisible, rejecting the idea that states could unilaterally withdraw. This ideological clash underscores the fundamental difference in how the two parties interpreted the Constitution and the nature of the American republic. The secession movement, therefore, was not just about states' rights but also about competing visions of national identity and governance.

Practically, the secession movement had immediate and far-reaching consequences. By February 1861, seven Southern states had seceded, forming the Confederate States of America. This act of defiance precipitated the Civil War, a conflict that would claim hundreds of thousands of lives and reshape the nation. For those studying this period, it’s crucial to examine primary sources such as the Declaration of the Immediate Causes of Secession issued by South Carolina. These documents provide insight into the motivations and rhetoric of secessionists, offering a clearer understanding of why they believed states' rights justified such drastic action.

In conclusion, the secession movement of 1860 was a pivotal moment in American history, driven by the Democratic Party’s Southern faction and their unwavering commitment to states' rights. It was a movement rooted in legal theory, economic self-interest, and cultural identity, yet it ultimately led to a catastrophic war. By examining its origins, strategies, and outcomes, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of states' rights and their role in shaping the nation’s future.

Robert Downey Jr.'s Political Party: Unveiling His Affiliation and Views

You may want to see also

States' Rights vs. Federalism

The 1860 U.S. presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, with the issue of states' rights versus federal authority at its core. The Democratic Party, deeply divided over slavery, emerged as the primary advocate for states' rights, particularly in the South. Their platform emphasized the sovereignty of individual states to determine their own policies, including the legality of slavery, in direct opposition to growing federal intervention. This stance was not merely a political strategy but a reflection of the South’s economic and cultural dependence on slave labor, which they feared would be threatened by a stronger federal government.

To understand the Democrats' position, consider the analytical framework of federalism as a balance of power. States' rights were seen as a safeguard against federal overreach, ensuring that local interests and traditions were preserved. For Southern Democrats, this meant protecting slavery as an institution vital to their agrarian economy. In contrast, the Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, championed federal authority to limit the expansion of slavery, viewing it as a moral and economic imperative. This ideological clash set the stage for the election and, ultimately, the Civil War.

A comparative analysis reveals the practical implications of these competing ideologies. Southern states, under the banner of states' rights, sought to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional, such as the Fugitive Slave Act. Northern states, meanwhile, used federalism to push for tariffs and internal improvements that benefited their industrial economies. The Democrats' support for states' rights was thus not a universal principle but a tool to defend specific regional interests. This selective application of states' rights highlights its limitations as a governing philosophy, as it often prioritized local autonomy over national unity.

Persuasively, one could argue that the Democrats' emphasis on states' rights was a reactionary stance, rooted in fear of change rather than a principled commitment to decentralization. By framing the debate as states' rights versus federal tyranny, they sought to rally Southern voters against perceived Northern aggression. However, this approach ignored the complexities of federalism, which requires a delicate balance between state and national authority. The Civil War would ultimately prove that states' rights could not be absolute without jeopardizing the Union itself.

Instructively, the 1860 election offers a cautionary tale for modern political discourse. Advocates of states' rights today often cite historical precedents like the Democrats of 1860, but they must recognize the context in which these arguments were made. States' rights should not be a shield for defending unjust practices, as it was with slavery. Instead, it should foster innovation and responsiveness at the local level while adhering to a shared national framework. Striking this balance requires nuanced policymaking, not rigid adherence to ideology.

Descriptively, the tension between states' rights and federalism in 1860 mirrored the geographical and cultural divides of the nation. The South's vast plantations and slave-dependent economy stood in stark contrast to the North's industrialized cities and wage-based labor. The Democrats' support for states' rights was a reflection of this regional identity, a last-ditch effort to preserve a way of life under threat. Yet, this focus on local control came at the expense of national cohesion, leading to a conflict that would redefine the role of the federal government in American life.

Can We Achieve Polite Communication in Today's Fast-Paced World?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party was the primary political party that strongly supported states' rights in 1860, particularly in the context of the debate over slavery and secession.

No, the Republican Party in 1860, led by Abraham Lincoln, emphasized federal authority and opposed the expansion of slavery, which clashed with the states' rights arguments of the South.

Southern Democrats strongly advocated for states' rights, particularly to protect slavery, while Northern Democrats were more divided, with some supporting states' rights but others seeking compromise to preserve the Union.

The Constitutional Union Party, formed in 1860, focused on preserving the Union and avoided taking a strong stance on states' rights, instead emphasizing adherence to the Constitution and existing laws.

![Civil War [Marvel Premier Collection]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81GCzQDerqL._AC_UY218_.jpg)