The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment aimed at guaranteeing equal rights for all citizens regardless of sex, has a complex legislative history intertwined with the efforts of multiple political parties. While the Democratic Party is often credited with championing the ERA, particularly through the leadership of figures like Alice Paul and Representative Martha Griffiths, who introduced the amendment in Congress in 1971, the Republican Party also played a significant role in its early stages. In fact, the ERA was first introduced in Congress in 1923 by Republican Senator Charles Curtis and Representative Daniel Read Anthony, Jr., both associated with the women’s suffrage movement. However, it was not until the 1970s, with bipartisan support, that the ERA gained substantial momentum, ultimately passing in the House and Senate before facing challenges during the ratification process. Thus, while the Democratic Party is frequently associated with its modern push, the origins of the ERA involved contributions from both major political parties.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of the Equal Rights Act: Which party initiated the legislation for gender equality in the workplace

- Democratic Party's Role: Did Democrats champion the Equal Rights Act in Congress

- Republican Contributions: Were Republicans key in drafting or supporting the Act

- Historical Context: What political climate led to the Act's introduction

- Key Figures Involved: Which politicians or leaders pushed for the Act's passage

Origins of the Equal Rights Act: Which party initiated the legislation for gender equality in the workplace?

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a landmark piece of legislation aimed at guaranteeing equal rights for women under the law, has a complex and often misunderstood history. While the ERA is commonly associated with the women's rights movement of the 1970s, its origins can be traced back to the early 20th century, and its legislative journey involved both major political parties. Contrary to popular belief, the ERA was not the brainchild of a single party but rather a bipartisan effort that evolved over decades.

Historical Context and Early Efforts

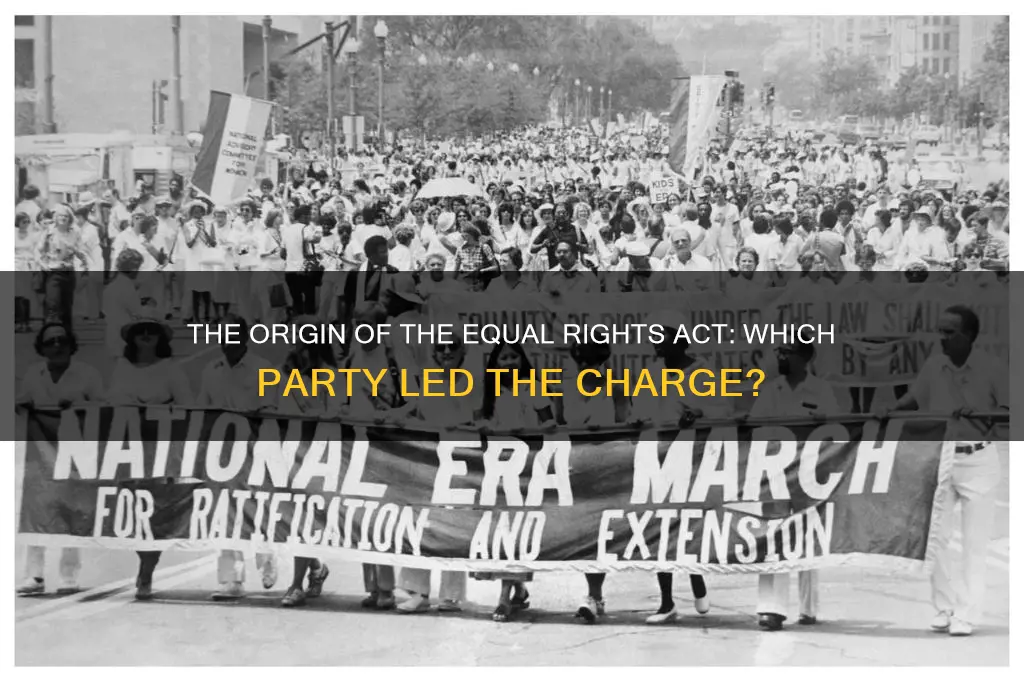

The roots of the ERA lie in the women’s suffrage movement, which culminated in the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Shortly after, Alice Paul, a prominent suffragist, drafted the ERA in 1923. The amendment stated simply: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." Initially, the ERA was championed by the National Woman's Party, a non-partisan organization. However, early attempts to pass the amendment were met with resistance, particularly from labor groups concerned about protective laws for women workers. Despite this, the ERA gained traction in the 1940s, with both Republicans and Democrats introducing versions of the amendment in Congress. For instance, in 1945, Republican Congresswoman Winifred Huck introduced the ERA, while Democratic Senator Claude Pepper supported it in the Senate. This early bipartisan support underscores that neither party exclusively "started" the ERA.

The 1970s and Bipartisan Momentum

The ERA’s most significant push came in the 1970s, fueled by the second-wave feminist movement. In 1972, the amendment passed both the House and Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support. In the Senate, the vote was 84-8, with a majority of both Democrats (43 out of 58) and Republicans (41 out of 42) voting in favor. Similarly, in the House, the vote was 354-24, with both parties showing strong support. President Richard Nixon, a Republican, endorsed the ERA, as did his Democratic successor, Jimmy Carter. This era highlights that the ERA was not a partisan issue but a shared goal across the political spectrum. However, the narrative often oversimplifies this history, attributing the ERA’s origins to one party or another.

Role of Individual Leaders

While the ERA was a bipartisan effort, individual leaders from both parties played pivotal roles in advancing the legislation. For example, Republican Congresswoman Martha Griffiths is often credited with reviving the ERA in the 1970s. She reintroduced the amendment in 1970 and successfully pushed it through the House. On the Democratic side, Representative Bella Abzug and Senator Birch Bayh were staunch advocates. These leaders demonstrate that progress on the ERA was driven by individuals committed to gender equality, regardless of party affiliation.

Takeaway: A Shared Legacy

The question of which party "started" the Equal Rights Act (or ERA) is a misframing of history. The ERA’s origins and advancement were the result of decades of bipartisan effort, driven by activists, legislators, and advocates from both major parties. While individual leaders and moments may be more prominently remembered, the ERA’s legacy is one of collaboration, not partisanship. Understanding this history is crucial for appreciating the ongoing struggle for gender equality and the role of cross-party cooperation in achieving legislative milestones.

Which Political Party Holds the Majority in Parliament Today?

You may want to see also

Democratic Party's Role: Did Democrats champion the Equal Rights Act in Congress?

The Democratic Party has historically been associated with progressive social policies, but its role in championing the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in Congress is a nuanced narrative. The ERA, first introduced in 1923, aimed to guarantee equal legal rights for all citizens regardless of sex. While the Democratic Party has often been at the forefront of civil rights issues, its support for the ERA has been marked by both leadership and internal divisions. Key Democratic figures, such as Representative Martha Griffiths and Senator Birch Bayh, played pivotal roles in reintroducing and advancing the ERA in the 1970s. Griffiths, in particular, was instrumental in securing House approval in 1971, demonstrating the party’s capacity to drive legislative progress on gender equality.

However, the Democratic Party’s role in the ERA’s journey cannot be viewed in isolation from broader political and social dynamics. While many Democrats championed the amendment, others, particularly those from conservative Southern states, opposed it. This internal divide mirrored the national debate, where concerns about the ERA’s implications for issues like abortion, military draft, and traditional gender roles created friction. The party’s inability to unify fully behind the ERA contributed to its eventual failure to secure ratification by the 1982 deadline, despite passing Congress with bipartisan support in 1972.

A comparative analysis reveals that while Democrats were essential in advancing the ERA, their efforts were often hindered by strategic miscalculations and external pressures. For instance, the party’s focus on other legislative priorities, such as economic policies and healthcare, sometimes overshadowed the ERA. Additionally, the rise of conservative opposition, including Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP ERA campaign, exploited fears and misinformation, further complicating Democratic efforts. This highlights the challenges of championing progressive legislation in a polarized political landscape.

To understand the Democratic Party’s role effectively, it’s instructive to examine specific actions and timelines. In 1972, after decades of stagnation, the ERA passed both chambers of Congress with significant Democratic support. However, during the ratification process, only 15 of the 33 states that ratified the amendment had Democratic-majority legislatures at the time. This suggests that while Democrats were crucial in congressional approval, state-level ratification efforts were less partisan, reflecting broader societal attitudes rather than party loyalty.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party’s role in championing the ERA in Congress was marked by both leadership and limitations. Key Democratic figures drove the amendment’s progress, but internal divisions and external opposition underscored the complexities of advancing gender equality legislation. This history serves as a reminder that while political parties can be catalysts for change, their success often depends on navigating broader social, cultural, and strategic challenges. For advocates today, this narrative offers practical insights: building bipartisan coalitions, addressing misinformation, and prioritizing sustained grassroots support are essential for advancing equality initiatives.

Who Said Personal is Political? Unraveling the Intersection of Identity and Activism

You may want to see also

Republican Contributions: Were Republicans key in drafting or supporting the Act?

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), first introduced in 1923, has a complex legislative history marked by bipartisan efforts and shifting political landscapes. While the Democratic Party is often associated with progressive social policies, Republicans played a significant role in the ERA's early stages. In 1943, for instance, Republican Congresswoman Winifred Huck introduced a revised version of the ERA, which gained traction and passed the Senate in 1950 with support from both parties. This early Republican involvement highlights a period when the ERA was not yet polarized along partisan lines.

Analyzing the 1970s, a pivotal decade for the ERA, reveals a more nuanced Republican contribution. In 1972, the ERA passed Congress with substantial Republican support: 47 of 176 House Republicans and 21 of 42 Senate Republicans voted in favor. Notably, Republican leaders like Senator Barry Goldwater and President Richard Nixon endorsed the amendment, with Nixon signing the joint resolution and stating, "I urge the prompt ratification of this constitutional amendment by the States." This era demonstrates that, at one point, the ERA was a bipartisan issue with key Republican figures advocating for its passage.

However, the narrative shifted dramatically in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the ERA became entangled in cultural and political battles. The rise of the conservative movement, led by figures like Phyllis Schlafly, mobilized opposition to the ERA, particularly within the Republican Party. By 1982, when the ratification deadline approached, many Republicans had withdrawn their support, and the party's platform began to reflect skepticism toward the amendment. This reversal underscores how Republican contributions to the ERA were not consistent but rather evolved in response to changing political dynamics.

Instructively, understanding Republican involvement in the ERA requires examining individual actions rather than party-wide uniformity. For example, Republican Congresswoman Marjorie Holt of Maryland was a vocal ERA supporter, working across party lines to advance the cause. Conversely, other Republicans, like Senator Jesse Helms, actively campaigned against it. This diversity within the party illustrates that while Republicans were not uniformly key in drafting or supporting the ERA, individual members and leaders made significant contributions during critical phases of its journey.

Persuasively, the question of Republican key involvement in the ERA hinges on perspective. If measured by early legislative efforts and bipartisan endorsements in the 1970s, Republicans were indeed instrumental. However, if judged by long-term commitment and ultimate impact, their role becomes more ambiguous. The ERA's failure to secure ratification by 1982 cannot be solely attributed to Republican opposition, but the party's shift away from support undoubtedly played a role. Thus, while Republicans were not the sole architects of the ERA, their contributions were pivotal in shaping its trajectory and eventual stall.

Washington's Second Term: The Birth of Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.65 $28.99

Historical Context: What political climate led to the Act's introduction?

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), not the Equal Rights Act, emerged from a tumultuous political climate marked by the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. This era saw women demanding legal, social, and economic equality, fueled by frustrations over persistent gender discrimination in employment, education, and family law. The Democratic Party, under President John F. Kennedy’s administration, established the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1961, which laid the groundwork for legislative action. However, it was the bipartisan effort in Congress, led by figures like Representative Martha Griffiths (D-MI) and Senator Birch Bayh (D-IN), that propelled the ERA’s introduction in 1972. This cross-party collaboration reflected a growing national consensus that constitutional protection for gender equality was overdue.

The political climate of the early 1970s was ripe for such a proposal, as the civil rights movement had already set a precedent for challenging systemic inequalities. The ERA’s introduction capitalized on this momentum, framing gender equality as the next logical step in America’s pursuit of justice. Yet, the ERA’s journey was not without contention. While the Democratic Party largely championed the amendment, it also garnered initial support from moderate Republicans, including President Richard Nixon, who endorsed it in 1972. This bipartisan backing, however, began to fracture as conservative backlash mounted, particularly from groups like the Eagle Forum, led by Phyllis Schlafly, who argued the ERA would undermine traditional family structures.

The ERA’s introduction also coincided with a broader cultural shift, as second-wave feminism challenged societal norms and demanded institutional change. High-profile cases like *Reed v. Reed* (1971), in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Equal Protection Clause applied to women, signaled a judicial willingness to address gender discrimination. This legal backdrop provided a strategic opportunity for advocates to push for constitutional protection, ensuring that future legislation and court decisions would be grounded in an explicit guarantee of equality. The ERA’s proposal was thus both a response to and a catalyst for this evolving political and cultural landscape.

Despite its initial promise, the ERA’s ratification process revealed deep political divisions. By 1977, 35 of the required 38 states had ratified the amendment, but the deadline for ratification was extended to 1982 amid fierce opposition. The failure to secure ratification by this deadline underscored the limits of bipartisan cooperation in the face of ideological polarization. The ERA’s history serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of political consensus and the enduring challenges of achieving constitutional change in a divided nation. Its legacy, however, continues to inspire contemporary efforts to enshrine gender equality in law.

Who's in Charge? Understanding the UK's Current Ruling Political Party

You may want to see also

Key Figures Involved: Which politicians or leaders pushed for the Act's passage?

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), not the Equal Rights Act, has been a cornerstone of the fight for gender equality in the United States. While the ERA never fully ratified, its history is marked by the tireless efforts of key political figures and leaders who championed its passage. Understanding their roles provides insight into the complexities of legislative advocacy and the enduring struggle for equal rights.

One of the most prominent figures in the ERA’s history is Alice Paul, a suffragist and feminist who drafted the amendment in 1923. Paul, a founding member of the National Woman’s Party, modeled the ERA after the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. Her strategic vision and unwavering commitment laid the groundwork for decades of advocacy. Paul’s approach was both analytical and instructive; she understood that legal equality required constitutional protection, not just legislative action. Her work exemplifies how a single individual’s persistence can shape a movement.

In the political arena, Representative Martha Griffiths played a pivotal role in advancing the ERA. Griffiths, a Democrat from Michigan, reintroduced the amendment in Congress in 1970, where it had languished for decades. Her persuasive speeches and bipartisan efforts led to its passage in the House and Senate in 1972. Griffiths’s ability to bridge party divides highlights the importance of pragmatic leadership in pushing for progressive legislation. Her success underscores a key takeaway: even in polarized environments, strategic collaboration can yield breakthroughs.

On the other side of the aisle, Republican Senator Charles Mathias of Maryland emerged as a critical ally. Mathias cosponsored the ERA in the Senate, demonstrating that support for gender equality was not confined to a single party. His comparative approach—framing the ERA as a matter of fundamental fairness rather than partisan politics—helped garner broader support. Mathias’s role serves as a cautionary reminder that progress often requires leaders willing to transcend ideological boundaries.

Beyond Congress, President Richard Nixon’s endorsement of the ERA in 1972 was a significant turning point. While Nixon’s support was partly strategic, it provided the amendment with presidential legitimacy. His administration’s descriptive rhetoric—portraying the ERA as a natural extension of American ideals—resonated with the public. However, Nixon’s involvement also illustrates the limitations of top-down advocacy; despite his backing, the ERA ultimately fell short of ratification.

Finally, the grassroots efforts of leaders like Bella Abzug, a Democratic congresswoman from New York, cannot be overlooked. Abzug, a fierce advocate for women’s rights, mobilized public support for the ERA through her descriptive and impassioned speeches. Her practical tips for activists—such as organizing local campaigns and leveraging media—were instrumental in keeping the amendment in the national spotlight. Abzug’s legacy reminds us that legislative change requires both high-level advocacy and ground-level mobilization.

In summary, the push for the ERA’s passage was driven by a diverse array of figures, each contributing unique strategies and perspectives. From Alice Paul’s visionary drafting to Martha Griffiths’s bipartisan efforts, Charles Mathias’s cross-party support, Richard Nixon’s presidential endorsement, and Bella Abzug’s grassroots mobilization, these leaders demonstrate the multifaceted nature of political advocacy. Their collective work offers a practical guide for future movements: success hinges on persistence, collaboration, and the ability to engage both institutions and communities.

Understanding Political Elites: Power, Influence, and Decision-Making Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Equal Rights Amendment was first introduced by the National Woman's Party in 1923, but it gained significant momentum when it was reintroduced by Democratic Congresswoman Martha Griffiths in 1970.

The Democratic Party played a leading role in advancing the ERA, particularly through the efforts of Congresswoman Martha Griffiths and later with strong support from Democratic President Jimmy Carter.

Initially, the ERA had bipartisan support, with both Democrats and Republicans endorsing it. However, it later became more polarized, with opposition primarily coming from conservative groups, including some within the Republican Party.

While opposition to the ERA was not exclusively tied to one party, conservative factions, particularly within the Republican Party, and groups like the Phyllis Schlafly-led STOP ERA campaign, were prominent in opposing its ratification.