The controversial policy of bussing, aimed at desegregating schools by transporting students to different districts, was prominently proposed and supported by the Democratic Party during the 1960s and 1970s. As part of broader efforts to address racial inequality and comply with federal court orders, such as the landmark *Brown v. Board of Education* decision, Democratic leaders and administrations, including President Lyndon B. Johnson and later President Jimmy Carter, advocated for bussing as a means to achieve racial integration in public schools. While the policy was intended to rectify decades of segregation, it sparked intense public debate, resistance, and political backlash, particularly in urban areas, where it became a divisive issue that influenced electoral politics and reshaped the political landscape.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origins of Bussing Policies

The concept of bussing, or the practice of transporting students to schools outside their local neighborhoods to achieve racial integration, has its roots in the mid-20th century United States. While often associated with liberal policies, the origins of bussing are more complex and bipartisan than commonly assumed. The 1954 Supreme Court decision in *Brown v. Board of Education* declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, but it did not provide a clear mechanism for implementation. This legal vacuum set the stage for bussing as a potential solution, though its proponents and opponents would span the political spectrum.

Analytically, the first significant push for bussing came from federal courts in the 1960s and 1970s, not directly from a political party. Judges, interpreting the *Brown* decision, ordered school districts to integrate, often mandating bussing as the most effective means. However, the Democratic Party, particularly under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, played a pivotal role in advancing civil rights legislation that indirectly supported these court orders. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 laid the groundwork for federal intervention in desegregation efforts, though they did not explicitly endorse bussing.

Instructively, it’s crucial to distinguish between the legal mandates and the political backlash. While the Democratic Party’s liberal wing championed integration, the Republican Party, under President Richard Nixon, initially opposed forced bussing. Nixon’s administration sought to appeal to white suburban voters by criticizing bussing as an overreach of federal power. However, this stance was not uniform; some moderate Republicans supported desegregation efforts, reflecting the party’s internal divisions. The issue became a political football, with both parties navigating the complexities of racial justice and voter sentiment.

Persuasively, the origins of bussing policies highlight the tension between legal imperatives and political pragmatism. Courts, driven by the mandate of *Brown v. Board of Education*, saw bussing as a necessary tool to dismantle segregation. Politicians, however, faced the challenge of balancing moral imperatives with electoral realities. The Democratic Party’s embrace of integration alienated some white voters, while the Republican Party’s opposition risked alienating minority communities. This dynamic underscores the difficulty of implementing policies that challenge deeply entrenched social structures.

Comparatively, bussing policies in the U.S. can be contrasted with desegregation efforts in other countries. For example, Canada’s approach to school integration relied more on neighborhood diversity and voluntary programs, avoiding the contentious bussing debates seen in the U.S. This comparison suggests that while bussing was a direct response to systemic segregation, it was not the only possible solution. Its adoption in the U.S. reflects the specific historical and legal context of American racial politics.

In conclusion, the origins of bussing policies are rooted in the legal mandate of *Brown v. Board of Education* and the subsequent federal court orders, rather than the direct proposal of a single political party. While the Democratic Party’s civil rights agenda provided a supportive framework, the issue transcended party lines, sparking debate and division within both major parties. Understanding this history offers insights into the challenges of implementing policies aimed at racial equity, particularly when they require significant social and political change.

Political Affiliations and Water Authorities: A Global Governance Perspective

You may want to see also

Democratic Party’s Role in Bussing

The Democratic Party's role in bussing is a complex and often misunderstood chapter in American political history. While the party is frequently associated with the policy, the reality is nuanced. Bussing, or the practice of transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods to achieve racial integration, was not exclusively a Democratic initiative. However, Democratic leaders and administrations played pivotal roles in its implementation and expansion, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s. This involvement was driven by the party's commitment to civil rights and desegregation, but it also sparked intense political and social backlash.

To understand the Democratic Party's role, consider the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision *Brown v. Board of Education*, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. While the ruling was a legal victory, its enforcement fell to federal and local governments. Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration took significant steps to address school segregation through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. These laws provided the legal and financial framework for bussing as a tool for integration. However, it was under the Nixon administration, a Republican presidency, that the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare began mandating bussing plans for districts with segregated schools. This historical context underscores that while Democrats championed the broader goals of integration, the mechanics of bussing involved both parties.

The Democratic Party's stance on bussing became a political liability in the 1970s, particularly after the 1974 *Milliken v. Bradley* decision, which limited the scope of bussing across district lines. Liberal Democrats, such as Senator Ted Kennedy, supported bussing as a necessary measure to combat entrenched segregation, while others within the party, like Senator Walter Mondale, sought to balance integration efforts with local concerns. This internal divide reflected broader societal tensions. Bussing became a rallying point for conservative opposition, with critics arguing it disrupted communities and imposed undue burdens on families. The policy's unpopularity contributed to the erosion of Democratic support in working-class and suburban areas, a trend that reshaped the party's electoral strategy in subsequent decades.

A critical takeaway is that the Democratic Party's role in bussing was not monolithic. While the party's leadership and base were largely aligned on the principle of racial integration, the implementation of bussing exposed fault lines within the party and the nation. For instance, the 1976 presidential campaign highlighted these divisions, with candidates like Jimmy Carter navigating the issue cautiously to appeal to both liberal and moderate voters. This pragmatic approach reflected the party's recognition of bussing's limitations as a policy tool and its unintended consequences, such as white flight and increased racial polarization.

In retrospect, the Democratic Party's involvement with bussing serves as a case study in the challenges of translating legal victories into societal change. While the policy advanced racial integration in some districts, it also underscored the complexities of addressing systemic inequality. Today, as debates over school segregation persist, the lessons of bussing remain relevant. Policymakers and advocates must consider not only the moral imperative of integration but also the practical and political realities of implementation. The Democratic Party's experience with bussing offers a cautionary tale about the importance of balancing ideals with feasibility in pursuit of equity.

Understanding Political Party Policies: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Stances

You may want to see also

Republican Opposition to Bussing

The Republican Party's opposition to bussing in the 1970s was a pivotal moment in the debate over school desegregation. At its core, this resistance was fueled by concerns about federal overreach, local control, and the perceived inefficiency of forced integration. Republicans argued that bussing disrupted communities, imposed unnecessary burdens on families, and often failed to achieve its intended goal of racial equality. This stance was not merely a reaction to the policy itself but a reflection of broader conservative principles emphasizing states' rights and individual choice.

Analytically, the Republican opposition to bussing can be understood through the lens of political strategy and ideological consistency. By framing bussing as an example of government overreach, Republicans tapped into widespread anxieties about federal intervention in local affairs. This narrative resonated particularly in suburban and rural areas, where voters were more likely to view bussing as an imposition rather than a solution. The party's leaders, including President Richard Nixon, leveraged this sentiment to solidify their base and appeal to white working-class voters who felt alienated by progressive policies.

Instructively, understanding Republican opposition to bussing requires examining the specific arguments they employed. One key claim was that bussing did not address the root causes of educational inequality, such as funding disparities and systemic racism. Instead, Republicans proposed alternatives like magnet schools and neighborhood-based integration efforts, which they argued were more practical and less disruptive. This approach allowed them to position themselves as advocates for educational reform without endorsing policies they deemed coercive.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that the Republican stance on bussing was not without its critics, even within the party. Some moderate Republicans, particularly in urban areas, acknowledged the necessity of desegregation efforts and questioned whether opposition to bussing was morally defensible. However, the party’s leadership largely succeeded in framing the issue as a matter of principle, emphasizing freedom of choice over mandated integration. This strategic framing helped Republicans maintain a unified front against bussing, despite internal disagreements.

Comparatively, the Republican opposition to bussing stands in stark contrast to the Democratic Party’s embrace of the policy as a tool for racial justice. While Democrats viewed bussing as a necessary step toward dismantling segregation, Republicans saw it as a symbol of liberal excess. This divergence highlights the deeper ideological divide between the two parties on issues of race, education, and federal power. The bussing debate thus became a proxy for broader disagreements about the role of government in addressing societal inequities.

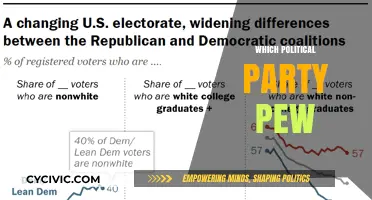

Descriptively, the impact of Republican opposition to bussing was profound, shaping the political landscape for decades. It contributed to the realignment of the American electorate, as white voters increasingly identified with the Republican Party’s emphasis on local control and individual rights. Simultaneously, the policy’s failure to achieve widespread desegregation underscored the limitations of federal intervention in the absence of broader societal support. Today, the legacy of this opposition continues to influence debates over school integration, with Republicans often advocating for market-based solutions like school choice as alternatives to forced bussing.

Understanding Family Politics: Dynamics, Power, and Relationships Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.64 $8.99

Bussing in the 1970s

The 1970s marked a pivotal era in American education, characterized by the contentious practice of bussing as a means to achieve racial desegregation in schools. While often associated with liberal policies, the origins of bussing are more nuanced. The Democratic Party, under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, laid the groundwork for desegregation efforts through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. However, it was the Supreme Court’s 1971 *Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education* decision that explicitly upheld bussing as a constitutional tool to address racial imbalance in schools. This ruling empowered federal judges to mandate bussing programs, but it was not a policy directly proposed by a political party. Instead, bussing became a judicially enforced measure, with Democrats generally supporting it as a means to fulfill civil rights promises and Republicans often opposing it as federal overreach.

Implementing bussing was far from straightforward. Cities like Boston, Detroit, and Los Angeles became flashpoints for resistance, with white communities protesting what they saw as forced integration and disruptions to neighborhood schools. The logistical challenges were immense: students faced longer commutes, schools struggled to accommodate diverse populations, and parents on both sides of the racial divide expressed frustration. For example, in Boston, the 1974 bussing program led to violent clashes and a sharp decline in white enrollment as families opted for private schools or moved to the suburbs. Despite these challenges, bussing did achieve measurable desegregation in some districts, with studies showing increased racial diversity in schools where it was rigorously enforced.

Critics of bussing, particularly within the Republican Party, argued that it was an ineffective and divisive solution to racial inequality. They contended that it ignored the root causes of segregation, such as housing policies and economic disparities, while alienating white voters. This opposition was strategically leveraged by Republicans, including President Richard Nixon, who initially supported desegregation efforts but later shifted to a more conservative stance. By the mid-1970s, the GOP began to frame bussing as a symbol of government intrusion, a narrative that resonated with white suburban voters and contributed to the party’s "Southern Strategy" to appeal to conservative Democrats in the South.

From a practical standpoint, bussing programs varied widely in scope and effectiveness. Some districts implemented "two-way bussing," transporting both white and minority students to achieve balance, while others relied on "one-way bussing," primarily moving minority students into predominantly white schools. The success of these programs often depended on community buy-in, administrative support, and supplementary initiatives like magnet schools and diversity training. However, by the late 1970s, public support for bussing had waned, and courts began to scale back mandates. The legacy of bussing remains complex: while it accelerated school desegregation in the short term, it also exposed deep racial and political divisions that continue to shape education policy today.

In retrospect, bussing in the 1970s was neither a purely Democratic nor Republican initiative but a judicially enforced measure that became a political lightning rod. Its implementation highlighted the challenges of translating legal mandates into societal change, particularly when addressing deeply entrenched racial inequalities. While bussing achieved some desegregation, its divisive nature and logistical hurdles underscore the limitations of top-down solutions. For educators and policymakers today, the bussing era serves as a cautionary tale: meaningful integration requires addressing systemic inequalities in housing, economics, and education, not just rearranging student populations.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Key Roles in Shaping Democracy

You may want to see also

Impact on Education and Politics

The concept of bussing, or the practice of transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods to achieve racial integration, was a highly controversial policy with profound implications for both education and politics. Historically, it was the Democratic Party that championed bussing as a means to address racial segregation in schools, particularly in the aftermath of the 1954 *Brown v. Board of Education* Supreme Court decision. While the policy aimed to dismantle systemic inequalities, its implementation revealed deep fissures in American society, sparking debates that continue to shape educational and political landscapes.

From an educational standpoint, bussing sought to create diverse learning environments, fostering cross-racial understanding and equalizing access to resources. However, its impact was mixed. In cities like Boston and Detroit, bussing led to protests, school boycotts, and heightened racial tensions, often undermining its intended goals. Studies show that while integrated schools can improve academic outcomes for minority students, the forced nature of bussing sometimes resulted in white flight, where white families moved to suburban districts to avoid integration. This unintended consequence exacerbated segregation in many areas, highlighting the complexities of using policy to engineer social change. Educators today grapple with these lessons, seeking more nuanced approaches to diversity and equity in schools.

Politically, bussing became a lightning rod issue, reshaping party alignments and public opinion. For Democrats, it symbolized a commitment to civil rights, but it also alienated working-class white voters who felt their communities were being disrupted. Republicans, led by figures like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, capitalized on this discontent, framing bussing as government overreach and a threat to local control. This narrative resonated with many voters, contributing to the realignment of the South and parts of the North toward the Republican Party. The bussing debate thus played a pivotal role in the rise of conservative politics in the late 20th century, illustrating how education policy can become a proxy for broader ideological battles.

To implement integration efforts effectively today, policymakers must learn from the bussing era. First, any initiative should prioritize community engagement to build trust and address concerns. Second, integration strategies should be voluntary wherever possible, offering incentives rather than mandates. For example, magnet schools and controlled-choice enrollment systems have shown promise in fostering diversity without coercion. Finally, addressing the root causes of segregation—such as housing inequality and funding disparities—is essential for sustainable change. By taking these steps, educators and politicians can work toward equitable schools without repeating the divisive mistakes of the past.

In conclusion, the legacy of bussing serves as a cautionary tale about the intersection of education and politics. While its goals were noble, its execution exposed the challenges of imposing integration from above. Today, as debates over school diversity persist, the lessons of bussing remind us that true equity requires not just policy change but also a commitment to inclusivity, empathy, and grassroots collaboration. By understanding this history, we can navigate current challenges with greater wisdom and effectiveness.

Understanding Political Raiding: Tactics, Impact, and Historical Context

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party, under the leadership of President Lyndon B. Johnson, supported and implemented bussing as part of the federal government's efforts to enforce school desegregation following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision.

The Republican Party largely opposed bussing, particularly during the 1970s, as many Republicans viewed it as federal overreach and an infringement on local control of schools. This opposition was a key part of the party's appeal to suburban and conservative voters.

The Republican Party, along with some conservative Democrats, introduced and supported legislation to limit or end bussing practices. For example, President Richard Nixon, a Republican, criticized bussing and sought to curb its use through policy changes and legal challenges.