The 1964 Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aimed to guarantee equal rights for women under the U.S. Constitution, was not passed into law but was introduced and championed primarily by the Democratic Party. The ERA was first proposed by Alice Paul, a prominent suffragist, in 1923, but it gained significant momentum in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1972, the amendment was passed by the U.S. Congress, with strong support from Democratic lawmakers, and sent to the states for ratification. Despite its initial bipartisan support, the ERA became a divisive issue, with conservative groups, particularly those aligned with the Republican Party, opposing it. Although the Democratic Party played a pivotal role in advancing the ERA, it ultimately fell short of the required number of state ratifications to become part of the Constitution.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of the ERA: Early 20th-century feminist movements pushed for gender equality, leading to the ERA's creation

- Legislative Push: The Democratic Party championed the ERA's passage in Congress during the Civil Rights era

- Key Supporters: Prominent Democrats like Rep. Martha Griffiths and President Kennedy backed the amendment

- Republican Role: Some Republicans supported the ERA, but the Democratic majority led its passage

- Post-1964 Challenges: Despite passing, the ERA faced ratification struggles in the following decades

Origins of the ERA: Early 20th-century feminist movements pushed for gender equality, leading to the ERA's creation

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a constitutional amendment aimed at guaranteeing equal rights for all citizens regardless of sex, was not passed in 1964. Instead, it was first introduced in Congress in 1923, just three years after the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote. The ERA's origins are deeply rooted in the early 20th-century feminist movements, which fought tirelessly for gender equality across various spheres of life. These movements laid the groundwork for the ERA, pushing it to the forefront of legislative discussions decades later.

Analytically, the early feminist movements of the 20th century were characterized by their multifaceted approach to gender equality. The National Woman's Party, led by Alice Paul, was a key player in advocating for the ERA. Unlike the suffrage movement, which primarily focused on voting rights, the National Woman's Party sought comprehensive legal equality. They argued that women needed equal protection under the law in employment, education, and property rights. This shift in focus from a single issue to a broader framework of equality was pivotal in shaping the ERA's content and purpose.

Instructively, understanding the ERA's origins requires examining the social and political climate of the early 1900s. The post-suffrage era saw women entering the workforce in greater numbers, yet they faced systemic discrimination and legal barriers. For instance, women were often paid less than men for the same work, and many states had laws restricting women's employment opportunities. Early feminists responded by organizing campaigns, lobbying legislators, and raising public awareness. Their efforts culminated in the drafting of the ERA, which succinctly stated, "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

Persuasively, the ERA's creation was not just a legislative act but a reflection of the enduring struggle for gender equality. Early feminists like Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman envisioned a society where women were not merely granted rights but were legally and socially equal to men. Their persistence in the face of opposition—often from within the political establishment—demonstrates the power of grassroots movements in driving constitutional change. While the ERA did not pass in 1964, its introduction in 1923 marked a turning point in the fight for gender equality, setting the stage for future legislative battles.

Comparatively, the ERA's origins highlight the contrast between the suffrage movement and the broader feminist agenda of the early 20th century. While suffrage was a critical milestone, it was only the beginning. The ERA represented a more ambitious goal: embedding gender equality into the Constitution itself. This distinction underscores the evolution of feminist thought, from securing basic political rights to demanding comprehensive legal and social parity. By examining this progression, we gain insight into the enduring relevance of the ERA and its continued impact on contemporary discussions about gender equality.

Founding Fathers' Views on Political Parties: Essential or Detrimental?

You may want to see also

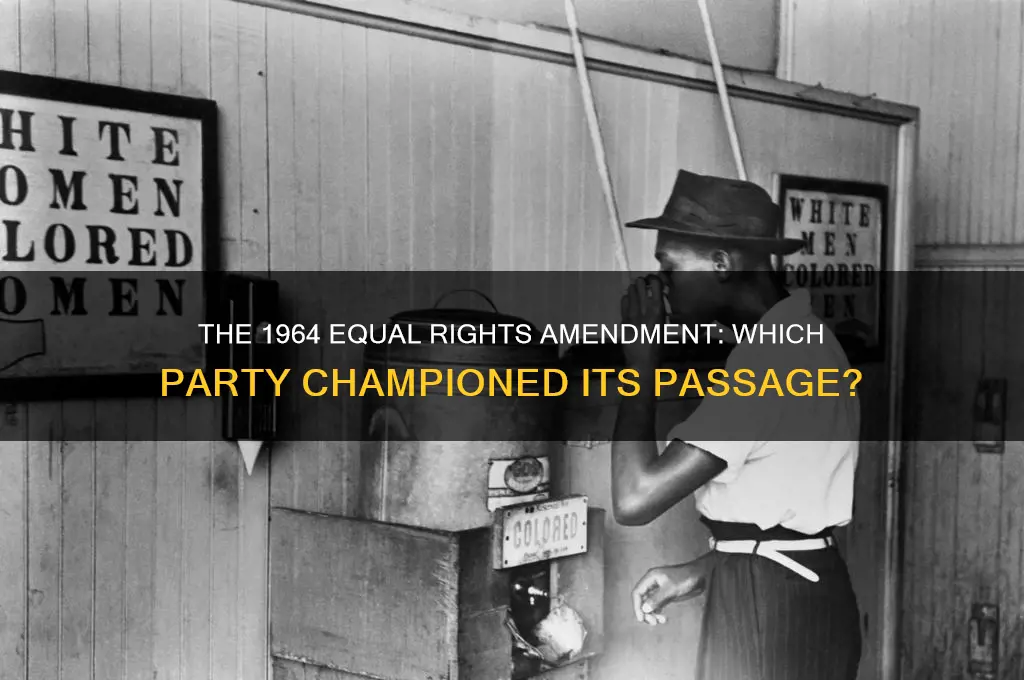

1964 Legislative Push: The Democratic Party championed the ERA's passage in Congress during the Civil Rights era

The 1964 legislative push for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a pivotal moment in American political history, deeply intertwined with the broader Civil Rights Movement. It was the Democratic Party that took the lead in championing the ERA's passage through Congress, reflecting the party's commitment to expanding equality beyond racial justice to include gender parity. This effort was not merely symbolic; it was a strategic move to codify women's rights into the Constitution, ensuring legal protections against discrimination based on sex. The ERA's journey through Congress in 1964 highlights the Democratic Party's role as a driving force in advancing progressive legislation during a tumultuous era.

To understand the Democratic Party's leadership in this effort, consider the political climate of 1964. The Civil Rights Act had just been signed into law, marking a significant victory for racial equality. However, women's rights advocates saw an opportunity to build on this momentum. The ERA, first introduced in 1923, had languished for decades, but Democratic leaders like Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan revitalized the push. Griffiths, a staunch feminist, successfully steered the ERA through the House of Representatives, where it passed with a bipartisan majority. This legislative victory was a testament to the Democratic Party's ability to mobilize support for progressive causes, even as it navigated internal divisions and external opposition.

The Senate's passage of the ERA in 1964 further underscores the Democratic Party's central role. Key Democratic senators, including George McGovern of South Dakota and Birch Bayh of Indiana, were instrumental in securing the necessary votes. Bayh, in particular, chaired the Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments and worked tirelessly to address concerns from both conservatives and labor groups, who feared the ERA might undermine protective labor laws for women. By framing the ERA as a natural extension of the Civil Rights Movement, Democrats positioned it as a moral imperative, aligning it with the broader struggle for equality. This strategic framing was crucial in gaining bipartisan support, though the bulk of the momentum came from Democratic lawmakers.

Despite the ERA's success in Congress, its journey was far from over. The amendment required ratification by three-fourths of the states, a process that would stall in the decades to follow. However, the 1964 legislative push remains a critical chapter in the ERA's history, demonstrating the Democratic Party's proactive role in advancing women's rights. This effort also highlights the intersectionality of the Civil Rights era, where the fight for racial equality and gender equality often converged. By championing the ERA, the Democratic Party not only addressed a longstanding issue of gender discrimination but also laid the groundwork for future feminist movements and legislative victories.

In retrospect, the 1964 legislative push for the ERA serves as a case study in how political parties can drive transformative change. The Democratic Party's leadership in this effort reflects its commitment to progressive ideals during a pivotal moment in American history. While the ERA's ultimate ratification remains incomplete, the 1964 congressional passage stands as a testament to the power of legislative advocacy and the enduring struggle for equality. For historians, activists, and policymakers, this chapter offers valuable insights into the complexities of advancing constitutional amendments and the role of political parties in shaping societal norms.

Discover Your Political Identity: Unraveling the Spectrum You Belong To

You may want to see also

Key Supporters: Prominent Democrats like Rep. Martha Griffiths and President Kennedy backed the amendment

The 1964 Civil Rights Act stands as a monumental legislative achievement, but the push for gender equality through the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) faced a more protracted battle. While the ERA itself wasn't passed in 1964, its journey through Congress was significantly shaped by key Democratic supporters.

Rep. Martha Griffiths, a Michigan Democrat, emerged as a tireless champion. She first introduced the ERA in 1955, facing consistent defeat until her strategic shift in 1970. Griffiths reframed the amendment as a matter of simple justice, arguing that women deserved equal protection under the law. Her persistence paid off in 1972 when the House finally passed the ERA with a resounding 354-24 vote.

President John F. Kennedy, though his presidency was cut short, played a crucial role in setting the stage for the ERA's eventual success. His administration actively supported women's rights initiatives, and he publicly endorsed the ERA in 1962. Kennedy's backing lent significant credibility to the cause, encouraging other Democrats to follow suit. His assassination in 1963 undoubtedly slowed momentum, but his legacy of support remained a powerful motivator for Democratic advocates.

The Democratic Party's embrace of the ERA wasn't unanimous. Some Southern Democrats, traditionally resistant to progressive social change, opposed the amendment. However, the party's leadership, influenced by figures like Griffiths and Kennedy, largely rallied behind the cause. This internal struggle within the Democratic Party highlights the complexities of political coalitions and the need for persistent advocacy to overcome entrenched resistance.

The ERA's journey demonstrates the power of individual leadership within a political party. Griffiths' unwavering dedication and Kennedy's early endorsement were instrumental in pushing the amendment forward. Their efforts, combined with the broader Democratic Party's eventual support, laid the groundwork for the ERA's passage in Congress. While the amendment ultimately fell short of ratification, the story of its Democratic champions serves as a reminder of the crucial role individual leaders play in advancing social justice causes.

Soccer and Politics: The Complex Intersection of Sport and Power

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Republican Role: Some Republicans supported the ERA, but the Democratic majority led its passage

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a landmark piece of legislation aimed at guaranteeing equal rights for women under the law, was a bipartisan effort, though its passage in 1972 (not 1964, as the ERA was first proposed in 1923 and passed by Congress in 1972) was primarily driven by a Democratic majority. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the role of Republicans who supported the amendment, as their contributions were instrumental in its advancement. While the Democratic Party held the majority in both the House and Senate during the ERA's passage, a significant number of Republicans crossed party lines to vote in favor of the amendment. This bipartisan support underscores the ERA's appeal as a fundamental issue of equality, transcending partisan politics.

Analyzing the voting records reveals a nuanced picture of Republican involvement. In the Senate, 18 out of 44 Republicans voted for the ERA, while in the House, 86 out of 174 Republicans supported it. Notable Republican figures, such as Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan, played pivotal roles in championing the amendment. Griffiths, who reintroduced the ERA in every congressional session from 1953 to 1970, was a staunch advocate for women's rights and worked tirelessly to build bipartisan support. Her efforts exemplify how individual Republican leaders could drive progress on issues of equality, even when their party’s overall stance was less unified.

Despite this Republican support, the Democratic majority was the driving force behind the ERA's passage. Democrats held 58% of the House and 60% of the Senate seats in 1972, and their overwhelming support (94% in the House and 90% in the Senate) ensured the amendment’s success. This majority not only provided the necessary votes but also shaped the legislative agenda, prioritizing the ERA amid other pressing issues. The Democratic Party’s commitment to the ERA reflected its broader platform of expanding civil rights and social justice during this era.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrasting dynamics within the two parties. While the Democratic Party’s support for the ERA was largely unified, the Republican Party’s stance was more divided. This division was influenced by emerging conservative movements within the GOP, which began to oppose the ERA on grounds of perceived threats to traditional family structures and states’ rights. However, the presence of Republican supporters demonstrates that the ERA was not solely a Democratic initiative but a cause that resonated across party lines, albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

In conclusion, while the Democratic majority led the passage of the ERA, the role of Republican supporters should not be overlooked. Their contributions were essential in demonstrating the amendment’s bipartisan appeal and in countering narratives that framed it as a partisan issue. Understanding this dynamic provides valuable insights into how cross-party collaboration can advance significant legislative reforms, even in polarized political climates. For advocates of equality today, this history serves as a reminder of the importance of building bridges across party lines to achieve lasting change.

Understanding Iran's Political System: The Islamic Republic's Unique Party Structure

You may want to see also

Post-1964 Challenges: Despite passing, the ERA faced ratification struggles in the following decades

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which sought to guarantee equal rights for women under the Constitution, was first introduced in 1923 but did not gain significant traction until the mid-20th century. Despite being passed by Congress in 1972, not 1964 as often misstated, the ERA faced a tumultuous journey toward ratification. By 1977, 35 of the required 38 states had ratified it, but the momentum stalled. The amendment’s deadline extensions and political backlash highlighted deep divisions, revealing how legislative success does not always translate into societal acceptance.

One of the primary challenges was the rise of organized opposition, led by figures like Phyllis Schlafly, who argued the ERA would undermine traditional family structures, eliminate gender-specific protections, and even force women into the military draft. This narrative resonated in conservative circles, particularly in the South and Midwest, where ratification efforts faltered. Schlafly’s STOP ERA campaign effectively mobilized grassroots opposition, framing the amendment as a threat to cultural norms rather than a step toward equality. Her tactics included disseminating misinformation and leveraging fears, which slowed progress in key states.

Another hurdle was the amendment’s time constraints. Initially given a seven-year ratification window, the ERA’s deadline was extended to 1982, but even this proved insufficient. States like Illinois, Florida, and North Carolina, which had initially supported the ERA, faced intense pressure to rescind their ratifications. By the deadline, only 35 states had ratified it, three short of the required number. This failure underscored the difficulty of sustaining political momentum over time, especially when faced with well-organized opposition.

The ERA’s struggles also reflected broader shifts in the political landscape. The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of the New Right, a conservative movement that prioritized traditional values and opposed feminist agendas. This ideological shift influenced state legislatures, making ratification increasingly difficult. Additionally, the ERA’s proponents lacked a unified strategy, with feminist groups often divided over tactics and priorities. These internal fractures weakened their ability to counter opposition effectively.

Today, the ERA remains unratified, though recent efforts in states like Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020) have reignited the debate. However, legal challenges persist, with questions about the validity of ratifications made decades after the original deadline. The ERA’s journey serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of constitutional change, demonstrating that passing legislation is only the first step in a long battle for societal transformation. Its legacy continues to inspire advocates, but the challenges it faced remind us of the enduring resistance to gender equality in American politics.

Volunteering for a Political Party: A Step-by-Step Guide to Getting Involved

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 1964 Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was not passed into law. However, it was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1971 and the Senate in 1972, with bipartisan support, though it did not secure enough state ratifications to become part of the Constitution.

The Democratic Party played a significant role in advancing the ERA. It was reintroduced in Congress in 1970 by Representative Martha Griffiths, a Democrat, and gained substantial Democratic support during its passage in the House and Senate in the early 1970s.

While some Republicans supported the ERA, the party’s stance became more divided over time. Initially, the ERA had bipartisan backing, but opposition grew, particularly from conservative groups, including some Republicans, during the ratification process.

Key figures included Democratic Representative Martha Griffiths, who reintroduced the ERA in 1970, and feminist leaders like Alice Paul, who drafted the original amendment in 1923. Bipartisan efforts in Congress were crucial for its approval in 1972.

The ERA failed to secure ratification by the required 38 states by the 1982 deadline due to opposition from conservative groups, led by figures like Phyllis Schlafly, who argued it would undermine traditional gender roles and family structures.