The question of which political party owned slaves is a complex and historically nuanced issue, deeply rooted in the early 19th-century United States. During this period, slavery was a widespread institution, and both major political parties of the time—the Democratic Party and the Whig Party—included members who were slaveholders. The Democratic Party, particularly in the South, was more closely associated with the defense of slavery, as its platform often aligned with the interests of plantation owners and the agrarian economy. However, individual members of the Whig Party, especially in the South, also owned slaves, though the party itself was more divided on the issue. The moral and political debates surrounding slavery eventually led to the emergence of the Republican Party in the 1850s, which was founded on an anti-slavery platform, further polarizing the nation and setting the stage for the Civil War. Understanding the historical context of slavery and its ties to political parties is crucial for comprehending the evolution of American politics and the enduring legacy of this institution.

Explore related products

$17.29 $27.95

What You'll Learn

Democratic Party's Historical Ties to Slavery

The Democratic Party's historical ties to slavery are deeply rooted in the 19th-century political landscape of the United States. During this period, the Democratic Party was the dominant political force in the Southern states, where slavery was a cornerstone of the economy and social structure. Prominent Democratic figures, including presidents like Andrew Jackson and John Tyler, were slaveholders. Jackson, for instance, owned over 150 enslaved individuals at his Hermitage plantation, and his policies, such as the Indian Removal Act, indirectly supported the expansion of slavery by clearing land for plantation agriculture. This era underscores the party’s early alignment with the institution of slavery, a fact often overlooked in modern political discourse.

Analyzing the Democratic Party’s platform during the mid-1800s reveals its staunch defense of slavery. The party’s 1848 and 1856 platforms explicitly endorsed the expansion of slavery into new territories, a position that directly opposed the growing abolitionist movement. Democrats like Senator John C. Calhoun became vocal advocates for states’ rights, a doctrine used to protect slavery from federal interference. The party’s leadership also played a pivotal role in the Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Act, a law that compelled Northerners to assist in the capture and return of escaped enslaved individuals. These actions highlight the Democratic Party’s active role in perpetuating and expanding the institution of slavery.

A comparative examination of the Democratic and Republican parties during this period further illuminates the Democrats’ ties to slavery. The Republican Party, founded in 1854, emerged as a direct response to the Democratic Party’s pro-slavery stance. While the Democrats championed slavery’s expansion, the Republicans, led by figures like Abraham Lincoln, advocated for its containment and eventual abolition. The 1860 presidential election, which pitted Lincoln against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, was a referendum on slavery’s future. Douglas’s support for popular sovereignty, which allowed territories to decide on slavery, was seen as a concession to pro-slavery interests. This contrast underscores the Democratic Party’s historical alignment with slavery in opposition to the emerging anti-slavery movement.

Understanding the Democratic Party’s historical ties to slavery requires acknowledging the post-Civil War era, known as Reconstruction. During this period, many Southern Democrats, known as “Redeemers,” resisted federal efforts to grant civil rights to formerly enslaved individuals. They employed tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence to disenfranchise Black voters and maintain white supremacy. The party’s association with groups like the Ku Klux Klan further solidified its legacy of racial oppression. While the Democratic Party eventually shifted its stance on civil rights in the mid-20th century, its historical ties to slavery and its aftermath remain a critical aspect of its legacy.

In practical terms, recognizing the Democratic Party’s historical ties to slavery offers valuable lessons for contemporary political discourse. It reminds us that political parties evolve over time, and their current platforms may bear little resemblance to their origins. For educators and historians, this history provides a nuanced narrative of American politics, challenging simplistic narratives of “good” and “evil” parties. For voters, understanding this history encourages critical engagement with political ideologies and their roots. By confronting this past, we can foster a more informed and empathetic dialogue about race, power, and justice in the United States.

Why PTT is Polite: Enhancing Communication with Respect and Efficiency

You may want to see also

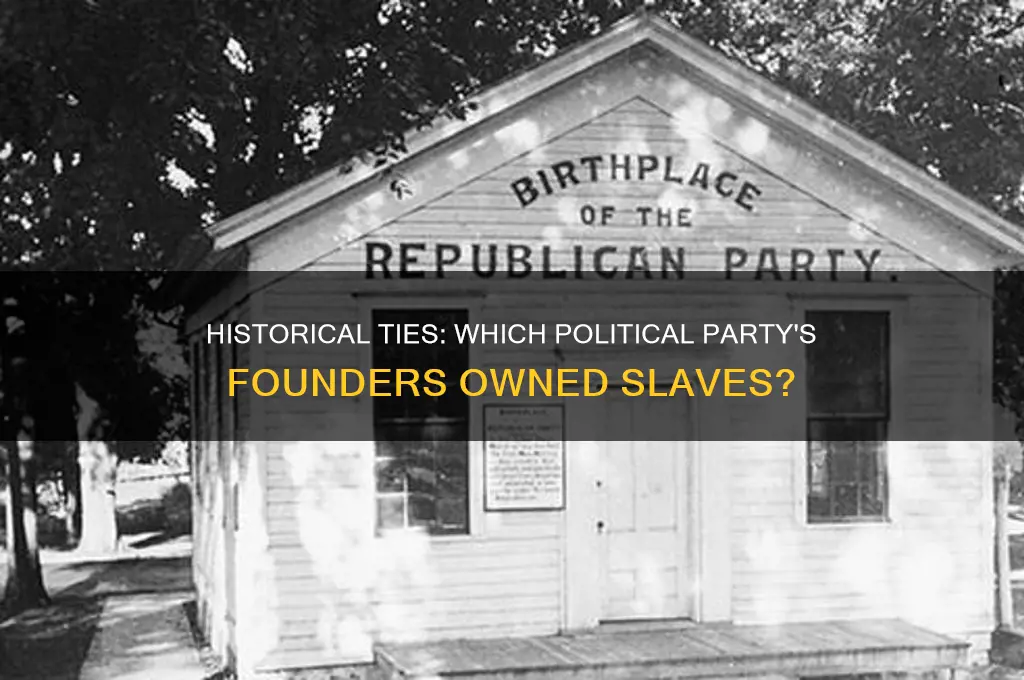

Republican Party's Stance on Abolition

The Republican Party, founded in 1854, emerged as a direct response to the moral and political crisis of slavery in the United States. Its formation was rooted in the principle of opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories, a stance that sharply contrasted with the Democratic Party’s more ambivalent position. Early Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, framed their mission as one of preventing the spread of what they called a "moral and political evil." This abolitionist lean was not merely rhetorical; it was enshrined in the party’s platform, which explicitly rejected the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s doctrine of popular sovereignty, which allowed territories to decide on slavery for themselves.

To understand the Republican Party’s stance on abolition, consider its strategic focus on containment rather than immediate eradication. Unlike more radical abolitionists who demanded the instant end of slavery everywhere, Republicans prioritized halting its growth. This pragmatic approach was both a political calculation and a moral compromise. By preventing slavery’s expansion, they aimed to gradually weaken its economic and political power, setting the stage for its eventual demise. This strategy is evident in Lincoln’s 1858 House Divided Speech, where he warned, "A house divided against itself cannot stand," emphasizing the nation’s untenable split over slavery.

A key example of the Republican Party’s abolitionist stance in action is the 1860 presidential election. Lincoln’s victory, achieved without a single Southern electoral vote, signaled a mandate for limiting slavery’s reach. His administration’s actions, including the Emancipation Proclamation and support for the 13th Amendment, were direct outgrowths of the party’s foundational principles. However, it’s crucial to note that these measures were not immediate or universal. The Emancipation Proclamation, for instance, applied only to states in rebellion, reflecting the party’s incremental approach to abolition.

Critics argue that the Republican Party’s stance on abolition was more politically expedient than morally pure. While the party opposed slavery’s expansion, many of its members were not outright abolitionists. Some, like Lincoln, initially supported colonizing freed slaves in Africa, a position that reflected racial prejudices of the time. This nuance highlights the complexity of the party’s stance: it was a coalition of anti-slavery activists, but not all members shared the same vision for racial equality. Practical tip: When analyzing historical political stances, distinguish between stated principles and the actions or beliefs of individual members.

In conclusion, the Republican Party’s stance on abolition was a defining feature of its early identity, shaped by a commitment to halting slavery’s spread rather than immediate eradication. This approach, while not without its limitations, laid the groundwork for the eventual end of slavery in the United States. By focusing on containment, the party navigated the political realities of its time while advancing a moral cause. This historical context offers valuable insights into how political movements balance idealism with pragmatism, a lesson relevant to contemporary debates on social and moral issues.

Understanding the Role and Influence of Political Doctrinaires in History

You may want to see also

Slave Ownership Among Southern Politicians

The historical record reveals a stark reality: slave ownership was pervasive among Southern politicians in the antebellum United States, particularly within the Democratic Party. This phenomenon wasn't merely a coincidence of geography or individual morality; it was deeply intertwined with the party's platform and the economic structure of the South.

A key example is John C. Calhoun, a prominent Democratic senator from South Carolina and vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Calhoun was a staunch defender of slavery, famously declaring it a "positive good" and arguing for its expansion into new territories. His own ownership of slaves on his Fort Hill plantation exemplified the alignment between his political ideology and personal interests.

This pattern wasn't limited to national figures. State-level politicians across the South, overwhelmingly Democrats, were also slaveholders. In Mississippi, for instance, a study of gubernatorial elections from 1798 to 1860 reveals that every single governor was a slave owner. This near-unanimity underscores the inextricable link between political power and slaveholding in the region.

Understanding this historical reality is crucial for comprehending the political dynamics leading up to the Civil War. The Democratic Party's staunch defense of slavery wasn't merely a philosophical stance; it was a defense of the economic and social system upon which their power base relied. This highlights the dangerous intersection of personal gain and political ideology, a lesson that resonates beyond the specific context of 19th-century America.

Estonia's Political Landscape: Which Party Holds the Majority?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Leaders Who Owned Slaves

The historical entanglement of political leaders with slavery reveals a complex and often uncomfortable truth: many figures who shaped nations were also slaveholders. This reality transcends party lines, as both Democratic and Republican leaders in the United States, for instance, have roots tied to this institution. Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father and Democratic-Republican, owned over 600 enslaved individuals at Monticello, despite penning the Declaration of Independence’s assertion of equality. Similarly, George Washington, the nation’s first president and a Federalist, held over 300 enslaved people at Mount Vernon. These examples underscore how slavery was deeply embedded in the political and economic fabric of early America, irrespective of party affiliation.

Analyzing the global context, the phenomenon of political leaders owning slaves is not confined to the United States. In Brazil, Emperor Pedro II, a monarch who ruled until 1889, owned enslaved individuals despite his later role in the abolition of slavery in Brazil. This paradox highlights the gradual and often contradictory nature of political leaders’ relationships with slavery. While some leaders eventually supported abolition, their personal histories as slaveholders complicate their legacies. Understanding these nuances is crucial for a balanced assessment of historical figures and their contributions to society.

A comparative examination of political parties and slavery reveals that the issue often transcended ideological boundaries. In the antebellum U.S., the Democratic Party in the South staunchly defended slavery, with leaders like John C. Calhoun advocating for its expansion. Conversely, the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party, included both abolitionists and those who tolerated slavery for political expediency. Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, famously opposed the expansion of slavery but initially focused on preserving the Union rather than immediate abolition. This complexity demonstrates that party platforms and individual beliefs did not always align neatly on the issue of slavery.

For those studying history or engaging in political discourse, it is instructive to approach this topic with a critical eye. Start by examining primary sources, such as plantation records or personal correspondence, to uncover the extent of leaders’ involvement with slavery. Pair this with secondary analyses that contextualize these actions within broader political and social movements. For instance, while Jefferson’s ownership of enslaved individuals is well-documented, exploring his contradictory views on slavery—as expressed in his writings—provides a fuller picture of his mindset. This method ensures a nuanced understanding of historical figures and their roles in perpetuating or challenging slavery.

Finally, the legacy of political leaders who owned slaves serves as a cautionary tale for modern politics. It reminds us that moral progress is often uneven and that leaders’ actions must be scrutinized beyond their stated ideals. For contemporary policymakers, this history underscores the importance of transparency and accountability. Practical steps include supporting initiatives that address systemic inequalities rooted in slavery and engaging in open dialogue about historical injustices. By confronting this past, societies can work toward a more equitable future, ensuring that the mistakes of history are not repeated.

The Dominant Party: 7 Presidents from 1820 to 1910

You may want to see also

Slavery's Influence on Early U.S. Politics

Slavery was not merely an economic institution in early U.S. history; it was a political force that shaped the very foundation of the nation’s governance. The Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, was deeply intertwined with slavery, as many of its members were Southern plantation owners. This party, which dominated early American politics, crafted policies that protected and expanded the institution of slavery, often at the expense of national unity. For instance, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, a bipartisan effort, was a direct response to the political tensions caused by the expansion of slavery into new territories. This compromise illustrates how slavery dictated legislative priorities and forced political parties to navigate its moral and economic complexities.

To understand slavery’s influence, consider the Three-Fifths Compromise of 1787, a provision in the U.S. Constitution that counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation and taxation purposes. This compromise was not just a moral concession but a political strategy. Southern states, predominantly aligned with the Democratic-Republican Party, gained disproportionate political power in Congress because of this provision. It allowed them to maintain a stronghold on federal policy, ensuring that slavery remained protected and profitable. This constitutional loophole highlights how slavery was embedded in the political DNA of the early U.S., influencing everything from electoral outcomes to legislative agendas.

The Whig Party, which emerged in the 1830s as an opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, initially avoided taking a strong stance on slavery to maintain a broad coalition. However, this neutrality was itself a political maneuver influenced by slavery. By refusing to challenge the institution directly, the Whigs inadvertently allowed slavery to persist as a divisive issue. This strategic ambiguity ultimately contributed to the party’s fragmentation, as Northern and Southern Whigs grew apart over the morality and legality of slavery. The Whigs’ failure to address slavery head-on underscores how the issue was a political minefield, shaping party platforms and alliances.

Slavery’s influence on early U.S. politics is also evident in the rise of the Democratic Party, which became the dominant political force in the South after the 1820s. The party’s leaders, such as John C. Calhoun, fiercely defended slavery as a "positive good" and used their political power to suppress abolitionist movements. The Gag Rule of 1836, which prevented Congress from discussing petitions related to slavery, is a prime example of how Southern Democrats wielded political control to silence opposition. This rule was not just a procedural tactic but a reflection of slavery’s grip on the political system, demonstrating how it stifled debate and perpetuated its own existence.

Finally, the formation of the Republican Party in the 1850s marked a turning point in slavery’s political influence. Founded on the principle of preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories, the Republican Party directly challenged the Democratic Party’s pro-slavery stance. This ideological clash culminated in the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, which triggered the secession of Southern states and the Civil War. The Republican Party’s rise illustrates how slavery’s influence on politics eventually led to a national reckoning, as the issue could no longer be contained within the compromises and concessions of earlier decades. Slavery’s role in shaping political parties and their agendas was thus both a cause and a consequence of the nation’s deepest divisions.

Eric Woolery's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party, as it existed in the 19th century, was closely associated with slaveholding interests, particularly in the South. Many prominent Democrats were slave owners, and the party defended slavery as an institution.

The Republican Party, founded in the 1850s, was primarily an anti-slavery party. While some early Republicans may have owned slaves, the party’s platform opposed the expansion of slavery and sought its eventual abolition.

The Whig Party, which existed from the 1830s to the 1850s, had members who owned slaves, particularly in the South. However, the party was more divided on the issue of slavery compared to the Democrats.

Slavery was largely confined to the Southern states, so Northern political parties, including the Republicans and Northern Whigs, had few if any members who owned slaves. Their focus was on limiting or ending slavery.