During the late 1700s, the Federalists, who championed a strong central government and the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, faced significant opposition from the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. This party, often referred to simply as the Jeffersonian Republicans, advocated for states' rights, limited federal authority, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution, contrasting sharply with the Federalists' vision of a more centralized and expansive national government. The rivalry between these two factions defined much of the early political landscape of the United States, shaping debates over economic policies, foreign relations, and the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

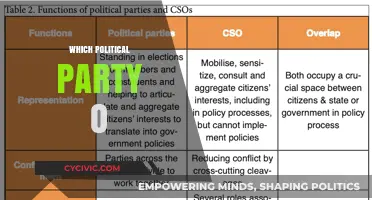

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Democratic-Republican Party |

| Founding Period | Late 1790s |

| Key Leaders | Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Aaron Burr |

| Ideological Stance | Anti-Federalist, States' Rights, Agrarianism |

| Central Beliefs | Limited federal government, strict interpretation of the Constitution |

| Economic Focus | Supported agrarian economy, opposed industrialization |

| Foreign Policy | Favored closer ties with France, skeptical of Britain |

| Support Base | Farmers, rural populations, and states' rights advocates |

| Opposition to Federalists | Opposed strong central government, national bank, and Hamiltonian policies |

| Major Achievements | Election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800, Louisiana Purchase |

| Decline | Gradually dissolved after the War of 1812, leading to the Second Party System |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- The Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, it favored states' rights and agrarian interests

- Anti-Federalist Movement: Opposed strong central government, advocating for individual liberties and local control

- Key Figures: Patrick Henry and George Mason led the opposition, criticizing the Constitution's ratification

- Philosophical Differences: Emphasized strict interpretation of the Constitution versus Federalist flexibility and implied powers

- Economic Views: Supported small farmers and rural economies, opposing Federalist pro-commerce and banking policies

The Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, it favored states' rights and agrarian interests

The late 1700s in American politics were marked by a sharp divide between two dominant factions: the Federalists and their staunch opponents, the Democratic-Republicans. Founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the Democratic-Republican Party emerged as a counterforce to Federalist centralization, championing states’ rights and agrarian interests. This ideological clash shaped the nation’s early political landscape, setting the stage for debates that resonate even today.

At the heart of the Democratic-Republican Party’s philosophy was a commitment to decentralized governance. Jefferson and Madison argued that power should reside primarily with the states, not the federal government. This stance was rooted in their belief that local communities understood their needs better than a distant central authority. For instance, while Federalists like Alexander Hamilton pushed for a strong national bank, Democratic-Republicans saw this as an overreach, fearing it would undermine state autonomy and favor urban commercial interests over rural farmers. This emphasis on states’ rights wasn’t merely theoretical; it was a practical response to the concerns of agrarian societies, which constituted the majority of the American population at the time.

Agrarian interests were another cornerstone of the Democratic-Republican platform. Jefferson, often referred to as the "Father of Democracy," idealized the yeoman farmer as the backbone of the nation. He believed that a society rooted in agriculture was more virtuous and stable than one dominated by commerce or industry. This vision was reflected in policies that favored land ownership, westward expansion, and reduced tariffs on agricultural goods. For example, the party supported the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation’s size and provided vast new territories for farming. In contrast, Federalists’ focus on manufacturing and trade was seen as a threat to the agrarian way of life, further deepening the divide between the two parties.

The Democratic-Republican Party’s rise also marked a shift in political participation. While Federalists tended to appeal to the elite and urban classes, Jefferson and Madison sought to mobilize the common man, particularly farmers and rural voters. Their party’s success in the 1800 election, known as the "Revolution of 1800," demonstrated the power of this grassroots approach. By framing their opposition to Federalists as a defense of ordinary Americans against aristocratic ambitions, they built a broad coalition that reshaped the nation’s political dynamics.

In retrospect, the Democratic-Republican Party’s legacy lies in its enduring influence on American political thought. Their advocacy for states’ rights and agrarian interests laid the groundwork for future debates about federalism and economic policy. While the party itself eventually evolved into the modern Democratic Party, its core principles continue to resonate in discussions about the balance of power between the federal government and the states. Understanding this historical context offers valuable insights into the roots of contemporary political divisions and the ongoing struggle to define the role of government in American society.

Political Polarization: Uniting Through Division for Stronger Democracy

You may want to see also

Anti-Federalist Movement: Opposed strong central government, advocating for individual liberties and local control

During the late 1700s, as the United States grappled with the question of governance, the Anti-Federalist movement emerged as a powerful counterforce to the Federalists. This movement was not merely a political faction but a philosophical stance rooted in a deep skepticism of centralized authority. Anti-Federalists feared that a strong central government would erode individual liberties and undermine the sovereignty of states. Their advocacy for local control and personal freedoms set them apart, offering a stark contrast to the Federalist vision of a consolidated national government.

To understand the Anti-Federalist perspective, consider their core argument: power concentrated in a distant federal authority would inevitably lead to tyranny. They pointed to historical examples, such as the British monarchy, to illustrate how unchecked central power could suppress local interests and individual rights. Anti-Federalists championed the idea that communities and states were better equipped to govern themselves, as they had a more intimate understanding of their unique needs and challenges. This belief was not just theoretical; it was grounded in the lived experiences of a populace wary of repeating the mistakes of the past.

One of the most practical contributions of the Anti-Federalists was their insistence on the inclusion of a Bill of Rights in the Constitution. They argued that without explicit protections for individual liberties—such as freedom of speech, religion, and the press—the new government could easily overstep its bounds. This advocacy was not merely a reactionary stance but a proactive measure to safeguard the rights of citizens. The eventual adoption of the Bill of Rights stands as a testament to the Anti-Federalists' influence, ensuring that the Constitution balanced federal authority with individual freedoms.

Comparatively, while Federalists like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison emphasized the need for a robust central government to ensure national stability and economic growth, Anti-Federalists like Patrick Henry and George Mason prioritized the preservation of local autonomy and personal liberties. This ideological divide was not just about governance structures but about the very essence of American identity. Anti-Federalists believed that a nation built on the principles of liberty and self-determination could not thrive under a centralized system that might stifle diversity and dissent.

In practical terms, the Anti-Federalist movement offers a timeless lesson in the importance of balancing power. Their advocacy for local control and individual rights serves as a reminder that governance should be responsive to the needs of the people it serves. For modern readers, this historical perspective underscores the value of decentralized decision-making and the need to vigilantly protect civil liberties. By studying the Anti-Federalists, we gain insights into how diverse voices and local perspectives can strengthen a nation, ensuring that power remains in the hands of the people rather than a distant elite.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Role in Shaping Government and Policies

You may want to see also

Key Figures: Patrick Henry and George Mason led the opposition, criticizing the Constitution's ratification

During the late 1700s, as the Federalist Party championed the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, a formidable opposition emerged, led by Patrick Henry and George Mason. These two figures, both influential Virginians, became the voices of the Anti-Federalists, a loosely organized group that feared the Constitution would centralize power and erode individual liberties. Their critiques were not mere dissent but a call to safeguard the principles of limited government and states’ rights.

Patrick Henry, renowned for his oratorical prowess, argued that the Constitution granted too much authority to the federal government. In his speeches, he warned that the document lacked a Bill of Rights, leaving citizens vulnerable to tyranny. Henry’s fiery rhetoric resonated with those who distrusted centralized power, particularly in rural areas. For instance, during the Virginia Ratifying Convention, he declared, “The Constitution is said to have beautiful features, but when I come to examine it, I find it dangerously defective.” His ability to articulate these fears made him a pivotal figure in the Anti-Federalist movement.

George Mason, a seasoned statesman and author of Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, took a more analytical approach. He meticulously critiqued the Constitution’s structure, particularly the absence of explicit protections for individual freedoms. Mason refused to sign the final draft at the Constitutional Convention, penning a list of objections that later influenced the Bill of Rights. His pragmatic concerns, such as the lack of safeguards against federal overreach, provided a substantive foundation for Anti-Federalist arguments. For those studying this period, Mason’s writings offer a detailed roadmap of early constitutional debates.

Together, Henry and Mason exemplified the Anti-Federalist strategy: combine emotional appeals with intellectual rigor. While Henry stirred public sentiment, Mason provided the legal and philosophical underpinnings. Their collaboration ensured that the opposition was not dismissed as mere obstructionism but recognized as a legitimate critique of the Constitution’s potential flaws. This dual approach forced Federalists to address concerns about individual liberties, ultimately leading to the addition of the Bill of Rights.

For modern readers, understanding Henry and Mason’s roles offers a practical lesson in political opposition. Their efforts demonstrate how critique can shape foundational documents, ensuring they better serve the people. By focusing on specific weaknesses—like the absence of a Bill of Rights—they transformed dissent into constructive dialogue. This historical example underscores the importance of balanced debate in constitutional governance, a principle as relevant today as it was in the late 1700s.

Working Class Politics: Which Party Truly Represents Labor Interests?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.7 $23

Philosophical Differences: Emphasized strict interpretation of the Constitution versus Federalist flexibility and implied powers

The late 1700s in American politics were marked by a profound philosophical divide between the Federalists and their opponents, the Democratic-Republicans, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. At the heart of this division was a fundamental disagreement over the interpretation of the Constitution. While Federalists championed a flexible reading that allowed for implied powers, their adversaries insisted on a strict, literal interpretation. This clash was not merely academic; it shaped the nation’s early policies, institutions, and identity.

Consider the Federalist approach as a craftsman who sees the Constitution as a living document, adaptable to the needs of a growing nation. They argued that the "necessary and proper" clause granted Congress the authority to take actions not explicitly listed but essential for governing effectively. For instance, Alexander Hamilton’s creation of the First Bank of the United States relied on this interpretation, despite no direct mention of banking in the Constitution. Federalists viewed such flexibility as vital for national stability and economic growth.

In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans approached the Constitution like a scientist adhering strictly to a formula. They believed that any power not explicitly granted to the federal government was reserved for the states or the people, as stated in the Tenth Amendment. Jefferson famously warned that loose interpretations could lead to tyranny, eroding individual liberties and state sovereignty. This philosophy was evident in their opposition to the Bank of the United States, which they deemed unconstitutional overreach.

This philosophical difference had practical implications. For example, Federalists supported a strong central government to foster commerce and industry, while Democratic-Republicans prioritized agrarian interests and local control. The debate over the Jay Treaty (1795) highlighted this divide: Federalists saw it as essential for economic ties with Britain, whereas their opponents viewed it as a betrayal of France and an overreach of federal authority.

To navigate this tension today, one might draw parallels to modern debates over executive power or federal versus state rights. A strict interpretation can safeguard against government overreach, but it may hinder progress in complex, evolving societies. Conversely, flexibility allows for adaptability but risks unchecked authority. The key takeaway is balance: understanding both perspectives ensures a Constitution that endures while remaining relevant. For instance, when evaluating contemporary policies, ask whether they align with the document’s original intent or if they stretch its boundaries for pragmatic purposes. This approach honors the framers’ vision while addressing current challenges.

Unveiling the Political Party Opposing Andrew Cuomo's Policies and Legacy

You may want to see also

Economic Views: Supported small farmers and rural economies, opposing Federalist pro-commerce and banking policies

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, emerged as the primary opposition to the Federalists in the late 1700s, championing the interests of small farmers and rural economies. This party’s economic philosophy was rooted in a deep skepticism of centralized power and a belief that the nation’s strength lay in its agrarian base. While Federalists favored pro-commerce policies, banking institutions, and industrial growth, Democratic-Republicans argued that such measures disproportionately benefited urban elites and threatened the independence of rural communities. This ideological clash shaped early American economic policy and highlighted the tension between competing visions of the nation’s future.

To understand the Democratic-Republicans’ stance, consider their advocacy for decentralized economic systems. They believed that small farmers, who constituted the majority of the population, were the backbone of the American economy. By supporting policies that protected land ownership, reduced taxes on agricultural products, and limited federal interference in local markets, they aimed to ensure that rural economies thrived. For instance, Jeffersonian policies often opposed tariffs that could harm farmers by increasing the cost of imported goods they relied on, such as tools and clothing. This focus on agrarian stability was not merely economic but also a moral and political stance, as it sought to preserve the self-reliance and virtue they associated with rural life.

In contrast to Federalist support for a national bank, Democratic-Republicans viewed such institutions as tools of corruption and inequality. They argued that banks concentrated wealth in the hands of a few, often urban merchants and financiers, while burdening small farmers with debt and interest payments. Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States, a cornerstone of Federalist economic policy, was a particular target of their criticism. Democratic-Republicans believed that hard currency, such as gold and silver, and local barter systems were more equitable and less prone to manipulation. This opposition to banking was not just theoretical; it reflected the lived experiences of rural Americans who often struggled with access to credit and faced exploitation by distant financial institutions.

A practical example of this economic philosophy in action can be seen in the Democratic-Republicans’ push for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. By acquiring vast western territories, Jefferson’s administration aimed to provide land for small farmers to expand and settle, thereby strengthening the agrarian base of the nation. This move not only supported rural economies but also aligned with their vision of a decentralized, self-sufficient America. In contrast, Federalists criticized the purchase as unnecessary and fiscally irresponsible, highlighting the stark differences in their economic priorities.

In conclusion, the Democratic-Republicans’ economic views were a direct response to Federalist policies that favored commerce and banking at the expense of rural interests. By championing small farmers and agrarian economies, they offered a counterbalance to the urban and industrial focus of their opponents. This ideological divide was not merely about economic policy but also about the identity and future of the United States. For those interested in early American history, understanding this conflict provides valuable insights into the enduring debate between centralized and decentralized economic systems. Practical takeaways include the importance of considering the impact of policies on diverse populations and the role of land and labor in shaping national economies.

The Conservative Party's Triumphant Return to Power in 1874

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, opposed the Federalists during the late 1700s.

The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while their opponents, the Democratic-Republicans, advocated for states' rights, agrarianism, and a more democratic government.

The opposition to the Federalists, led by the Democratic-Republicans, shaped early American politics by fostering a two-party system, emphasizing the importance of limited government, and influencing key policies such as the Bill of Rights and the Louisiana Purchase.