The question of which political party moved Social Security to the general fund is a complex and often misunderstood aspect of U.S. fiscal history. Social Security, established in 1935 under the Social Security Act, has always been funded through dedicated payroll taxes and held in trust funds separate from the federal government's general fund. However, there have been instances where surplus Social Security funds were used to offset deficits in the general fund, effectively commingling the two. This practice, often referred to as unified budgeting, began in the 1960s under the Johnson administration and continued under both Democratic and Republican leadership. While no single party exclusively moved Social Security to the general fund, both parties have, at various times, supported policies that allowed surplus Social Security revenues to be used for general government spending, leading to ongoing debates about the program's financial sustainability and independence.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- FDR's New Deal Legacy: Social Security's creation and initial funding structure under Roosevelt's administration

- Unification: Johnson administration's move of Social Security into the unified federal budget

- Fiscal Implications: How the shift affected federal deficits and trust fund accounting

- Political Motivations: Reasons behind the decision, including Vietnam War funding pressures

- Long-Term Consequences: Impact on Social Security's solvency and public perception of the program

FDR's New Deal Legacy: Social Security's creation and initial funding structure under Roosevelt's administration

Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal legacy is indelibly marked by the creation of Social Security, a program that fundamentally reshaped the American social safety net. Enacted in 1935 as part of the Social Security Act, this program was designed to provide financial security to the elderly, the unemployed, and vulnerable children during the Great Depression. FDR envisioned Social Security as a self-sustaining system, funded through payroll taxes rather than general revenue, to ensure its stability and insulate it from political whims. This initial funding structure was a deliberate choice, reflecting Roosevelt’s commitment to creating a program that would endure beyond his administration.

The funding mechanism for Social Security was straightforward yet innovative: a dedicated payroll tax levied on both employers and employees. In 1937, the tax rate began at 1% on the first $3,000 of earnings, with the revenue deposited into a trust fund specifically designated for Social Security benefits. This trust fund model was critical to FDR’s vision, as it created a firewall between Social Security and the federal government’s general fund, safeguarding the program’s finances from being diverted to other purposes. This structure also fostered public trust by ensuring that the money workers paid into the system would directly fund their future benefits.

Despite FDR’s careful design, the question of whether Social Security funds were ever moved to the general fund has persisted in political discourse. Historically, the trust fund model has remained intact, but debates over its management have flared periodically. For instance, in the 1960s, the Social Security trust funds were consolidated with the general fund for accounting purposes, though this was a bookkeeping change rather than a redirection of funds. This move, often misconstrued as a shift to the general fund, was intended to streamline federal budgeting but did not alter the program’s dedicated revenue stream.

FDR’s New Deal legacy in Social Security’s creation underscores the importance of its initial funding structure as a bulwark against political interference. By establishing a trust fund financed through payroll taxes, Roosevelt ensured that Social Security would remain a distinct and protected program. This design has allowed Social Security to survive nearly a century of political and economic shifts, providing a critical safety net for millions of Americans. As debates continue over the program’s future, FDR’s foresight in creating a self-sustaining funding model remains a cornerstone of its resilience.

How Political Parties Shape Congressional Members' Decisions and Actions

You may want to see also

1968 Unification: Johnson administration's move of Social Security into the unified federal budget

In 1968, the Johnson administration made a pivotal decision to integrate Social Security into the unified federal budget, a move that reshaped the financial landscape of the program. This action, often referred to as the "1968 Unification," marked the first time Social Security funds were commingled with the general fund of the U.S. Treasury. Prior to this, Social Security revenues and expenditures were accounted for separately, creating a firewall that protected the program’s finances from being used for other government purposes. The unification was part of a broader effort to streamline federal budgeting, but it also opened the door to debates about the program’s fiscal independence and long-term sustainability.

The decision to unify Social Security with the general fund was driven by both practical and political considerations. From a practical standpoint, the Johnson administration sought to simplify the federal budgeting process by consolidating all government revenues and expenditures into a single framework. This approach aimed to provide a clearer picture of the nation’s fiscal health and make it easier to manage deficits and surpluses. However, critics argued that this move undermined the trust fund structure of Social Security, which had been designed to ensure that payroll taxes were dedicated exclusively to the program’s beneficiaries. By blending Social Security funds with the general fund, the program became more vulnerable to being used to offset other government spending, potentially jeopardizing its solvency.

Politically, the 1968 Unification reflected the Democratic Party’s priorities under President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was committed to expanding the Great Society programs. By integrating Social Security into the unified budget, the administration gained greater flexibility to fund its ambitious domestic agenda without appearing to increase the deficit. This strategic maneuver allowed Johnson to maintain the appearance of fiscal responsibility while pursuing expansive social policies. However, it also set a precedent that would later be criticized for blurring the lines between Social Security’s dedicated funding and general government revenues.

The long-term implications of the 1968 Unification remain a subject of debate. On one hand, the move facilitated a more holistic approach to federal budgeting, enabling policymakers to consider Social Security within the broader context of national finances. On the other hand, it raised concerns about the program’s financial security, as the commingling of funds made it easier for politicians to use Social Security surpluses to mask deficits in other areas of the budget. This tension highlights the trade-offs inherent in fiscal policy and underscores the importance of transparency and accountability in managing trust fund programs.

For individuals and policymakers alike, understanding the 1968 Unification is crucial for navigating contemporary discussions about Social Security reform. While the move was intended to modernize federal budgeting, it also introduced complexities that continue to shape debates about the program’s future. Practical tips for engaging with this issue include examining the annual Social Security Trustees Report, which provides insights into the program’s financial status, and advocating for policies that prioritize the long-term solvency of Social Security. By learning from the lessons of 1968, stakeholders can work toward solutions that balance fiscal responsibility with the program’s mission to provide economic security for retirees, survivors, and individuals with disabilities.

Welfare Dependency: Analyzing Political Party Affiliations and Public Assistance Usage

You may want to see also

Fiscal Implications: How the shift affected federal deficits and trust fund accounting

The unification of the Social Security Trust Funds into the federal budget under President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968 marked a pivotal shift in fiscal policy. Prior to this, Social Security revenues and expenditures were accounted for separately, creating the illusion of a self-sustaining program. By moving these funds into the general fund, Social Security’s surpluses were effectively used to offset deficits in other areas of the federal budget. This change obscured the program’s long-term solvency issues, as surpluses were spent rather than saved, and introduced a new dynamic to federal deficit accounting. The immediate effect was a reduction in the reported deficit, but at the cost of long-term financial stability for Social Security.

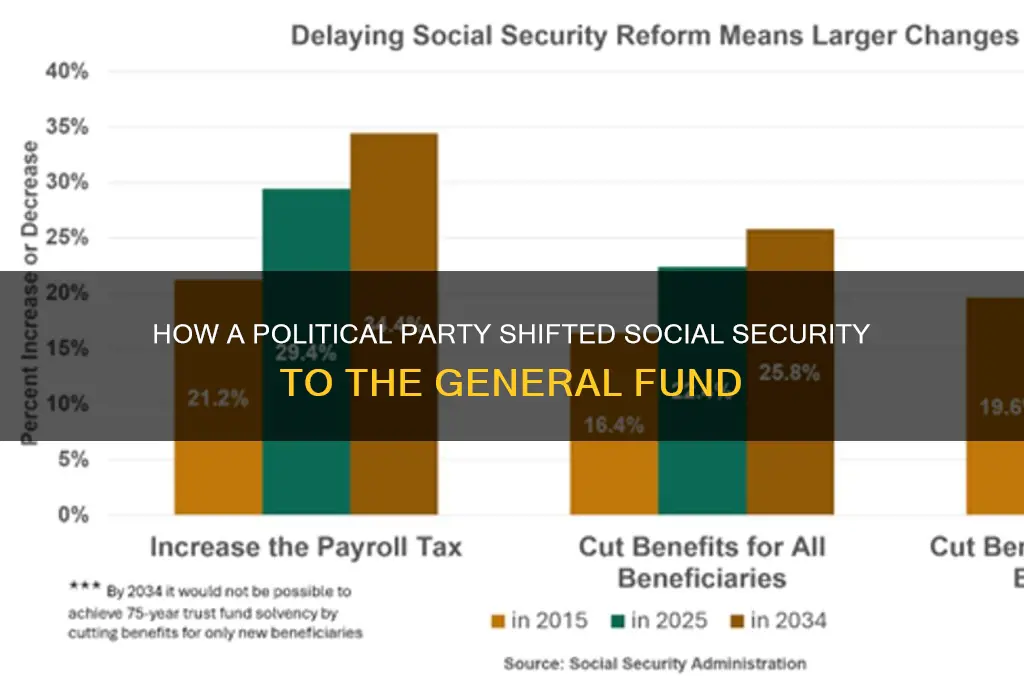

Analyzing the fiscal implications reveals a trade-off between short-term budgetary relief and long-term sustainability. When Social Security surpluses were unified with the general fund, they artificially lowered the federal deficit, making the government’s fiscal position appear healthier than it was. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, Social Security surpluses masked the true size of deficits caused by tax cuts and increased spending. However, this practice also meant that funds intended for future retirees were spent on current obligations, leaving the trust fund with non-marketable Treasury securities rather than cash reserves. This accounting maneuver delayed necessary reforms and exacerbated the program’s funding gap.

From a practical standpoint, the shift complicated trust fund accounting and eroded public trust in Social Security’s financial health. The trust fund’s surpluses were invested in government bonds, which were essentially IOUs from the Treasury. While these bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, they do not represent real assets that can be liquidated to pay benefits. As the trust fund’s balance grew, so did the government’s obligation to repay it, creating a circular liability. This accounting method obscured the distinction between Social Security’s dedicated revenue stream and general tax revenues, making it harder for policymakers and the public to assess the program’s true financial condition.

To address these challenges, policymakers must reconsider the relationship between Social Security and the federal budget. One potential solution is to restore the trust fund’s independence by prohibiting the use of its surpluses to offset other spending. Another approach is to reform the budget process to account for trust fund obligations more transparently. For instance, adopting a “unified budget” that excludes trust fund transactions would provide a clearer picture of the government’s fiscal health. Additionally, increasing public awareness of Social Security’s funding structure could build support for necessary reforms, such as raising the payroll tax cap or adjusting benefit formulas.

In conclusion, the shift of Social Security to the general fund had profound fiscal implications, distorting deficit reporting and undermining the program’s long-term solvency. While it provided temporary budgetary relief, it created a structural imbalance that requires urgent attention. By reevaluating trust fund accounting practices and fostering transparency, policymakers can restore confidence in Social Security and ensure its viability for future generations. This is not merely a technical issue but a critical step toward fiscal responsibility and intergenerational equity.

Should You Declare a Political Party? Understanding the Pros and Cons

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Motivations: Reasons behind the decision, including Vietnam War funding pressures

The decision to move Social Security funds to the general fund was not a sudden policy shift but a calculated move driven by overlapping fiscal and political pressures. One of the most significant catalysts was the escalating cost of the Vietnam War, which strained the federal budget to its limits. By the mid-1960s, war expenditures had soared to over $2 billion per month, forcing the Johnson administration to seek creative ways to balance the budget without raising taxes or cutting popular domestic programs. Social Security, with its substantial surplus at the time, became a tempting target for reallocation. This move allowed the government to use those funds to offset war costs while maintaining the appearance of fiscal responsibility.

Analyzing the political motivations reveals a strategic effort to avoid public backlash. The Johnson administration, already under fire for the war’s mounting casualties and costs, sought to shield Social Security beneficiaries from direct cuts. By moving the surplus to the general fund, the administration effectively blurred the lines between Social Security’s dedicated funding and the broader federal budget. This maneuver enabled them to fund the war without explicitly raiding Social Security, a program with broad bipartisan support. However, this decision set a precedent for treating Social Security as a general revenue source rather than a protected trust fund, raising questions about its long-term sustainability.

The role of political expediency cannot be overstated. Democrats, who controlled both the White House and Congress at the time, faced the challenge of funding an unpopular war while maintaining their base of support. Moving Social Security funds to the general fund provided a short-term solution, allowing them to allocate resources to the war effort without alienating older voters, a key demographic for the party. This decision, however, came at the cost of eroding the firewall between Social Security and the federal budget, a move that would later be criticized as fiscally irresponsible.

Comparatively, Republicans initially opposed this reallocation, arguing it undermined the integrity of Social Security. However, their stance softened as they recognized the political benefits of avoiding tax increases or drastic spending cuts. This bipartisan acquiescence highlights how fiscal pressures can override ideological differences, particularly when national security is at stake. The Vietnam War served as a unique stress test for federal budgeting, revealing the lengths to which policymakers would go to fund a war without triggering public outrage.

In retrospect, the decision to move Social Security to the general fund was a pragmatic yet problematic response to the fiscal demands of the Vietnam War. It exemplifies how wartime pressures can reshape fiscal policies, often with long-term consequences. While it provided temporary relief, it also set a precedent for treating Social Security as a piggy bank for general government spending. This history serves as a cautionary tale for policymakers today, underscoring the need to protect dedicated funds from being co-opted for unrelated purposes, even in times of crisis.

When Oscars Turned Political: A Historical Shift in Hollywood's Spotlight

You may want to see also

Long-Term Consequences: Impact on Social Security's solvency and public perception of the program

The move of Social Security funds into the general fund, a decision historically attributed to both Democratic and Republican administrations, has had profound long-term consequences on the program's solvency and public perception. By commingling these dedicated payroll taxes with general revenues, the government effectively blurred the lines between Social Security’s financial health and the broader federal budget. This decision, often justified as a short-term fiscal maneuver, has led to a structural vulnerability: Social Security’s surplus revenues, once held in a trust fund, are now subject to the whims of annual budgeting and political priorities. As a result, the program’s solvency is increasingly tied to the federal government’s overall financial stability, which has been marked by recurring deficits and debt ceiling crises.

Analytically, the impact on solvency is clear. When Social Security surpluses are used to offset deficits in the general fund, the program’s trust fund accumulates special-issue Treasury bonds rather than cash reserves. While these bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, they represent an intra-governmental IOU rather than a liquid asset. As the trust fund’s bond holdings grow, the government’s ability to redeem them depends on its capacity to raise revenues or borrow—a precarious position in an era of escalating national debt. By 2034, the Social Security Administration projects that the trust fund will be depleted, at which point benefits would need to be cut by approximately 20% unless Congress acts. This looming shortfall is a direct consequence of treating Social Security revenues as part of the general fund, rather than safeguarding them as a dedicated resource.

Public perception of Social Security has also been significantly altered by this fiscal integration. Initially designed as a self-sustaining program with a clear social contract—workers pay into the system and receive benefits in retirement—Social Security is now often viewed through the lens of federal spending and deficits. This shift has fueled misconceptions that the program is a drain on the budget, despite the fact that it has run a surplus for decades. Politically, this narrative has been exploited to justify calls for benefit cuts or privatization, eroding public confidence in the program’s long-term viability. Polls consistently show that younger generations, in particular, are skeptical about receiving full benefits, a sentiment exacerbated by the program’s entanglement with general fund politics.

To mitigate these consequences, policymakers must take decisive steps to restore Social Security’s financial independence. One practical solution is to reintroduce a firewall between Social Security revenues and the general fund, ensuring that payroll taxes are exclusively used to fund the program. Additionally, Congress could explore revenue-enhancing measures, such as lifting the payroll tax cap or gradually increasing the tax rate, to address the projected shortfall. Public education campaigns could also play a critical role in clarifying how Social Security operates and dispelling myths about its financial status. By refocusing the narrative on the program’s self-funding nature, policymakers can rebuild trust and ensure its solvency for future generations.

In conclusion, the decision to move Social Security funds into the general fund has had far-reaching implications for both the program’s solvency and its public image. While this move provided temporary fiscal relief, it has created a structural vulnerability that threatens the program’s long-term stability. Addressing this issue requires not only financial reforms but also a concerted effort to reshape public understanding of Social Security’s role in the federal budget. By taking these steps, policymakers can safeguard the program’s future and uphold its promise to millions of Americans.

Exploring Jamaica's Political Landscape: Major Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Neither major political party has moved Social Security to the general fund. Social Security funds are held in trust funds separate from the general fund, as established by law.

No, the Democratic Party has not moved Social Security to the general fund. Social Security remains in its designated trust funds, independent of the general fund.

No, the Republican Party has not moved Social Security to the general fund. The program’s funds are still managed through the Social Security Trust Funds, separate from the general fund.

While there have been debates and proposals about Social Security’s funding and management, no major political party has successfully moved Social Security to the general fund. It remains in its dedicated trust funds.