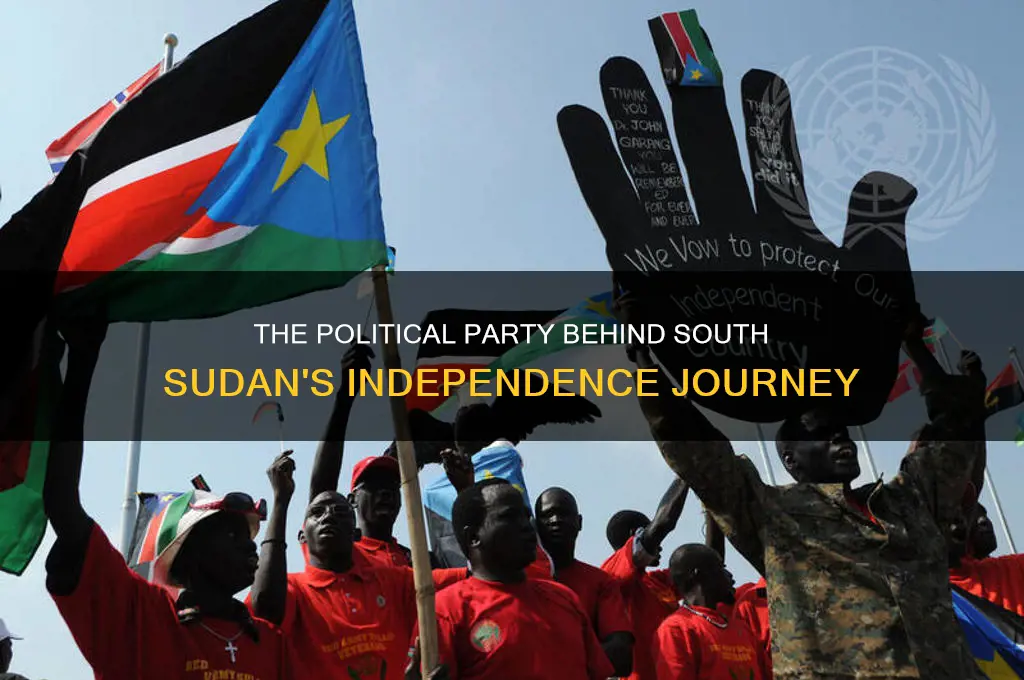

The journey to South Sudan's independence was significantly shaped by the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), a political party that emerged from the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005). Under the leadership of figures like John Garang and later Salva Kiir, the SPLM championed the cause of self-determination for the predominantly Christian and animist southern Sudanese population, who had long been marginalized by the Arab-dominated government in Khartoum. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005, brokered with the SPLM's involvement, laid the groundwork for a referendum on independence, which was held in January 2011. The overwhelming majority of South Sudanese voted in favor of secession, leading to the formal declaration of independence on July 9, 2011, with the SPLM playing a central role in guiding the nation toward sovereignty.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) |

| Founded | 1983 |

| Founder | Dr. John Garang de Mabior |

| Ideology | Secessionism (initially), Social democracy, Pan-Africanism |

| Role in Independence | Led the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) against the Sudanese government, culminating in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) which granted South Sudan autonomy and a referendum on independence. |

| Referendum Result | 98.83% voted for independence in the 2011 referendum |

| Independence Date | July 9, 2011 |

| Current Status | Ruling party in South Sudan, though facing internal divisions and criticism for governance issues |

| Key Figures | Salva Kiir Mayardit (current President of South Sudan and SPLM leader), Riek Machar (former Vice President and SPLM-IO leader) |

| Challenges | Internal power struggles, ethnic tensions, economic difficulties, ongoing violence |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Role of the SPLM/A

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) was the driving force behind South Sudan's independence, a journey marked by decades of armed struggle and political maneuvering. Founded in 1983 by John Garang, the SPLM/A emerged as a response to the marginalization and oppression of southern Sudanese by the Khartoum-based government. Their initial goal was to establish a united, secular Sudan, but the persistence of northern dominance led to a shift in focus toward self-determination for the south. This transformation laid the groundwork for the eventual secession in 2011.

Analyzing the SPLM/A’s role reveals a dual identity: a military force and a political movement. As an army, the SPLM/A waged one of Africa’s longest civil wars, leveraging guerrilla tactics to counter the Sudanese government’s superior resources. Their ability to mobilize southern communities and sustain a prolonged insurgency was pivotal. Politically, the SPLM/A evolved into a negotiating entity, culminating in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). This agreement granted South Sudan autonomy and paved the way for the 2011 independence referendum, where 98.8% of voters chose secession.

However, the SPLM/A’s legacy is not without controversy. Internal divisions, often along ethnic lines, plagued the movement, foreshadowing the instability that would later grip independent South Sudan. John Garang’s death in 2005 exacerbated these fractures, as his successor, Salva Kiir, struggled to unify the party. Despite these challenges, the SPLM/A’s role in securing independence remains undeniable, making it the central actor in South Sudan’s quest for sovereignty.

To understand the SPLM/A’s impact, consider this practical takeaway: their success was rooted in adaptability. They transitioned from a rebel group to a governing party, navigating both battlefield and diplomatic arenas. For movements seeking self-determination, the SPLM/A’s example underscores the importance of balancing military pressure with political engagement. However, their post-independence struggles serve as a cautionary tale about the need for inclusive leadership and institutional stability.

In conclusion, the SPLM/A’s role in South Sudan’s independence is a testament to resilience and strategic evolution. While their achievements are historic, the movement’s challenges highlight the complexities of transitioning from liberation struggle to state-building. Studying the SPLM/A offers valuable insights for both historical analysis and contemporary efforts toward self-determination.

Justice Jamie Grosshans' Political Party Affiliation: Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Key leaders in the movement

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) was the primary political party that spearheaded South Sudan's journey to independence. Within this movement, several key leaders played pivotal roles in shaping the nation's destiny. Their leadership, vision, and sacrifices were instrumental in mobilizing the South Sudanese people and navigating the complex path to sovereignty.

One of the most prominent figures was Dr. John Garang de Mabior, the founding leader of the SPLM and its armed wing, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA). Garang, a former colonel in the Sudanese army, emerged as a charismatic and strategic leader. His ability to unite diverse ethnic groups under a common cause was unparalleled. Garang's vision of a "New Sudan"—a united country based on equality and justice—inspired millions, though his sudden death in a helicopter crash in 2005 left a void in the movement. His legacy, however, continued to fuel the struggle for independence.

Following Garang's death, Salva Kiir Mayardit assumed leadership of the SPLM. Kiir, a seasoned military commander and Garang's longtime deputy, shifted the movement's focus toward achieving independence for South Sudan. His pragmatic approach and deep roots in the SPLA earned him respect among the ranks. As the first president of independent South Sudan, Kiir faced the daunting task of nation-building, though his tenure has been marked by challenges, including internal conflicts and governance issues.

Another critical figure was Riek Machar, a PhD-holder in engineering and a key SPLM leader. Machar's intellectual prowess and political acumen made him a formidable force within the movement. However, his relationship with the SPLM was tumultuous, marked by defections and reconciliations. Despite these divisions, Machar's contributions to the independence struggle, particularly in mobilizing support and negotiating with the Sudanese government, cannot be overlooked. His role as vice president post-independence further underscores his significance in South Sudan's political landscape.

Lastly, Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior, widow of John Garang, emerged as a powerful voice for peace and unity. Her advocacy for women's rights and her efforts to bridge ethnic divides have made her a respected figure both within South Sudan and internationally. Nyandeng's leadership exemplifies the role of women in the independence movement, highlighting their resilience and influence in shaping the nation's future.

These leaders, each with their unique strengths and challenges, formed the backbone of the SPLM's struggle for independence. Their collective efforts, marked by sacrifice and determination, laid the foundation for South Sudan's emergence as Africa's newest nation. Understanding their roles provides invaluable insights into the complexities of the independence movement and the ongoing efforts to build a stable and prosperous South Sudan.

Unveiling Ted Bundy's Political Affiliation: A Surprising Party Connection

You may want to see also

Referendum process and outcomes

The 2011 South Sudan independence referendum stands as a pivotal moment in the nation’s history, marking the culmination of decades of struggle and negotiation. Held from January 9 to 15, 2011, the referendum was the result of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005 between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Government of Sudan. This process was not merely a vote but a carefully orchestrated mechanism to determine the future of Southern Sudan, offering its people the choice between remaining united with Sudan or seceding to form an independent state. The referendum’s outcome, with 98.83% of voters opting for independence, was a resounding affirmation of the SPLM’s leadership and the aspirations of the Southern Sudanese people.

The referendum process was governed by strict criteria to ensure fairness and legitimacy. Voters had to be at least 18 years old, a resident of Southern Sudan, and registered through a meticulous identification process. Over 3.7 million people registered, with voting centers established across Southern Sudan and in eight countries with significant South Sudanese diaspora populations. The African Union, United Nations, and international observers monitored the process to prevent fraud and ensure transparency. Despite logistical challenges, such as inaccessible rural areas and limited infrastructure, the referendum proceeded with remarkable efficiency, a testament to the organizational capabilities of the SPLM and the determination of the electorate.

Analyzing the outcomes reveals the profound impact of the SPLM’s leadership. The party had long advocated for self-determination, framing independence as the solution to decades of marginalization and conflict. The overwhelming vote for secession was not just a rejection of unity with Sudan but an endorsement of the SPLM’s vision for a sovereign South Sudan. However, the referendum also exposed underlying tensions within the region, including disputes over borders, oil revenues, and citizenship rights. These issues would later contribute to internal conflicts within South Sudan, highlighting the complexities of transitioning from liberation movement to governing party.

A comparative perspective underscores the uniqueness of South Sudan’s referendum. Unlike other secessionist movements, such as Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia, South Sudan’s process was formally sanctioned by an international agreement and conducted under global scrutiny. This legitimacy was crucial in gaining international recognition, with the new state admitted to the United Nations just days after declaring independence. Yet, the referendum’s success also set a precedent for other regions seeking self-determination, raising questions about the balance between national sovereignty and the right to secession in international law.

Instructively, the South Sudan referendum offers practical lessons for future independence movements. First, a clear and unified leadership, as demonstrated by the SPLM, is essential for mobilizing public support and navigating complex negotiations. Second, international involvement, while beneficial for legitimacy, must be balanced with local ownership to ensure the process reflects the will of the people. Finally, post-referendum planning is critical; South Sudan’s experience highlights the need for robust institutions and inclusive governance to address the challenges of statehood. For those studying or involved in similar processes, these insights provide a roadmap for achieving and sustaining independence.

Understanding Left-Wing Political Parties: Ideologies, Goals, and Global Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

International support and recognition

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) was the primary political party that spearheaded South Sudan's struggle for independence. However, the success of this movement was not solely an internal affair; it was significantly bolstered by international support and recognition. This external backing played a pivotal role in legitimizing the SPLM’s cause and pressuring the Sudanese government to negotiate.

One of the most critical forms of international support came from the United States, which became a vocal advocate for South Sudan’s right to self-determination. Through diplomatic channels, economic sanctions, and humanitarian aid, the U.S. exerted pressure on Khartoum while providing resources to the SPLM. For instance, the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which paved the way for the 2011 independence referendum, was heavily mediated by U.S. diplomats. Practical tip: When analyzing international support, always trace the timeline of diplomatic interventions to understand their cumulative impact.

African nations also played a crucial role in recognizing and supporting South Sudan’s independence. The African Union (AU) and regional bodies like the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) provided a platform for negotiations and ensured that the SPLM’s grievances were heard on a continental stage. Kenya and Uganda, in particular, offered logistical support and safe havens for SPLM leaders during the conflict. Comparative analysis reveals that regional solidarity often amplifies the effectiveness of international recognition, as it aligns with shared geopolitical interests.

European countries and international organizations contributed through humanitarian aid and development programs, which indirectly strengthened the SPLM’s position by alleviating suffering in war-affected areas. The European Union, for example, funded infrastructure projects and peacekeeping missions post-independence, signaling long-term commitment to South Sudan’s stability. Caution: While humanitarian aid is vital, it should not overshadow the need for political solutions, as over-reliance on aid can create dependency rather than self-sufficiency.

Finally, the United Nations’ role in monitoring the 2011 referendum and its subsequent recognition of South Sudan as a sovereign state cemented the international community’s endorsement of the SPLM’s efforts. This recognition was not merely symbolic; it opened doors for South Sudan to join global institutions like the UN and access international funding. Takeaway: International recognition is a powerful tool in state-building, but it must be accompanied by sustained support to address the challenges of newly independent nations.

Exploring the Diversity of Political Parties in the National Assembly

You may want to see also

Challenges during the independence struggle

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) played a pivotal role in South Sudan's journey to independence, but this path was fraught with immense challenges. One of the primary obstacles was the complex and often violent relationship with the Sudanese government in Khartoum. The struggle for independence was not merely a political negotiation; it was a protracted conflict marked by two civil wars spanning over five decades. The First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972) and the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) were characterized by brutal fighting, with the SPLM and its armed wing, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), at the forefront of the southern resistance.

The Human Cost and Strategic Dilemmas

The human toll of these conflicts was devastating. Estimates suggest that over 2 million people lost their lives, primarily in the south, due to violence, famine, and disease. The SPLA, led by figures like John Garang, faced the daunting task of not only fighting a well-equipped Sudanese army but also managing internal divisions and maintaining popular support. The movement had to navigate the delicate balance between military strategy and political objectives, ensuring that their armed struggle did not alienate the very people they aimed to liberate. This involved making difficult choices, such as deciding when to engage in peace talks and when to intensify military operations.

International Dynamics and Resource Constraints

The independence struggle was further complicated by international dynamics and resource limitations. The SPLM/A received support from various countries, including Ethiopia, Uganda, and, at times, the United States, but this support was often contingent on regional power struggles and shifting geopolitical interests. Managing these external relationships while maintaining a unified front was a significant challenge. Additionally, the movement had to contend with limited resources, especially during the early years, which affected their ability to sustain a prolonged war effort and provide for the civilian population in the liberated areas.

Unity in Diversity: A Political Challenge

South Sudan's diversity presented another layer of complexity. The region is home to numerous ethnic groups, each with its own interests and historical grievances. The SPLM had to foster a sense of national unity while respecting these diverse identities. This involved intricate political maneuvering, ensuring that the movement's leadership and policies represented the aspirations of all southern Sudanese. The challenge was to create a cohesive political entity capable of negotiating with Khartoum and, eventually, governing an independent state.

In the final stages of the struggle, the SPLM's ability to adapt and negotiate was crucial. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005, which paved the way for the 2011 independence referendum, was a result of years of diplomatic efforts and strategic compromises. This agreement, however, did not mark the end of challenges, as the newly independent South Sudan soon faced internal conflicts and governance issues, highlighting the enduring complexities of nation-building.

How Political Parties Shape Public Policy: Key Strategies and Tactics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) was the primary political party that led South Sudan to independence.

The SPLM, through its armed wing the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), fought a long struggle against the Sudanese government, culminating in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which paved the way for the 2011 independence referendum.

Dr. John Garang de Mabior was the founding leader of the SPLM until his death in 2005. After his passing, Salva Kiir Mayardit took over and led the movement to independence.

While the SPLM was the dominant force, other Southern Sudanese political groups and civil society organizations also played roles in advocating for self-determination and independence.

The SPLM negotiated the CPA in 2005, which granted South Sudan autonomy and set the stage for a referendum on independence. In 2011, the referendum resulted in an overwhelming vote for secession, leading to South Sudan's independence on July 9, 2011.