Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics, with both major parties accused of engaging in this tactic to secure electoral advantages. While instances of gerrymandering can be found across the political spectrum, recent analyses and legal challenges have highlighted a disproportionate number of cases involving Republican-controlled state legislatures redrawing maps to dilute Democratic voting power, particularly in key battleground states. However, Democrats have also been implicated in gerrymandering efforts, albeit to a lesser extent, in states where they hold legislative control. The debate over which party is more guilty of gerrymandering often hinges on the frequency, scale, and impact of these actions, as well as the broader political and legal contexts in which they occur. Ultimately, the pervasive nature of gerrymandering underscores the need for systemic reforms, such as independent redistricting commissions, to ensure fair and impartial electoral processes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical cases of gerrymandering by Democrats

While both major U.S. political parties have engaged in gerrymandering, historical cases involving Democrats offer critical insights into the tactics and consequences of this practice. One notable example occurred in Illinois during the 1980s and 1990s, where Democrats redrew congressional districts to dilute Republican voting strength. The infamous "earmuff" district, connecting Chicago to the state’s southern tip via a thin strip of land, was designed to pack Republican voters into fewer districts while maximizing Democratic representation. This maneuver exemplifies how gerrymandering can distort electoral outcomes, even in a nominally democratic process.

In Maryland, Democrats have been accused of gerrymandering to maintain their political dominance in a state where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans 2-to-1. The 2011 redistricting plan, spearheaded by Democratic Governor Martin O’Malley, was particularly egregious. It targeted the 6th Congressional District, held by Republican Roscoe Bartlett, by redrawing its boundaries to include heavily Democratic areas. This shift flipped the district from Republican to Democratic in the 2012 election, illustrating how gerrymandering can effectively nullify the will of local voters.

Another case emerged in North Carolina during the 1990s, though often overshadowed by later Republican efforts, Democrats initially drew maps favoring their candidates. In 1992, Democrats controlled the redistricting process and created districts that packed African American voters into a few majority-minority districts, diluting their influence in surrounding areas. While this strategy aimed to comply with the Voting Rights Act, it also served to consolidate Democratic power by ensuring safe seats in those districts.

These historical cases reveal a recurring pattern: Democrats, like their Republican counterparts, have exploited redistricting to entrench their political advantage. While the specifics vary by state, the underlying strategy remains consistent—manipulating district boundaries to favor one party at the expense of fair representation. Critics argue that such practices undermine democratic principles, regardless of the party responsible. Understanding these examples is crucial for addressing gerrymandering comprehensively, as it highlights the need for nonpartisan redistricting reforms to restore electoral integrity.

Politics and Finance: How Government Policies Shape Economic Outcomes

You may want to see also

Historical cases of gerrymandering by Republicans

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, has a long and contentious history in the United States. While both major political parties have engaged in this tactic, the Republican Party has been particularly prominent in recent decades. Historical cases of gerrymandering by Republicans reveal a strategic effort to consolidate power, often at the expense of fair representation. One notable example is the 2010 redistricting cycle, where Republicans, leveraging their control of state legislatures following the midterm elections, redrew maps in key states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and North Carolina. These efforts resulted in disproportionately favorable outcomes for Republican candidates, even when their overall vote share did not significantly outpace their Democratic counterparts.

Consider the case of North Carolina in 2011, where Republicans controlled the redistricting process after gaining a majority in the state legislature. Despite a nearly even split in statewide votes between Democrats and Republicans, the newly drawn congressional map yielded a 10-3 Republican advantage in the U.S. House delegation. This outcome was not accidental but a direct result of packing Democratic voters into a few districts and cracking others across multiple districts to dilute their influence. The map was so extreme that it was later struck down by federal courts for violating the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act, though not before it had secured Republican dominance for several election cycles.

Analyzing these cases reveals a pattern of intentionality and sophistication. Republicans have employed advanced data analytics and mapping software to precision-engineer districts that maximize their electoral gains. For instance, in Wisconsin in 2011, Republicans drew a state assembly map that allowed them to win 60 of 99 seats with just 48.6% of the statewide vote. This efficiency gap, as it’s often called, underscores the effectiveness of their gerrymandering strategies. Critics argue that such tactics undermine democratic principles by distorting the principle of "one person, one vote" and reducing the competitiveness of elections.

However, defenders of these practices often argue that gerrymandering is a legitimate tool within the rules of the political game. They point to the fact that the party in power has historically redrawn maps to their advantage, suggesting that Republicans are merely following precedent. Yet, this perspective ignores the disproportionate impact of recent Republican gerrymandering, which has been facilitated by technological advancements and a lack of federal oversight following the Supreme Court’s 2013 gutting of the Voting Rights Act. The result has been a systemic tilt in favor of Republican candidates, raising questions about the fairness and legitimacy of electoral outcomes.

Practical efforts to combat gerrymandering have gained momentum in recent years, with some states adopting independent redistricting commissions to remove the process from partisan hands. For example, California established such a commission in 2010, leading to more competitive districts and a reduction in partisan bias. While these reforms offer a path forward, the legacy of Republican gerrymandering remains a significant challenge. Voters and advocates must remain vigilant, pushing for transparency and fairness in redistricting processes to ensure that electoral maps reflect the will of the people, not the interests of one party.

Understanding Voter Demographics: Who Participates in Political Elections and Why

You may want to see also

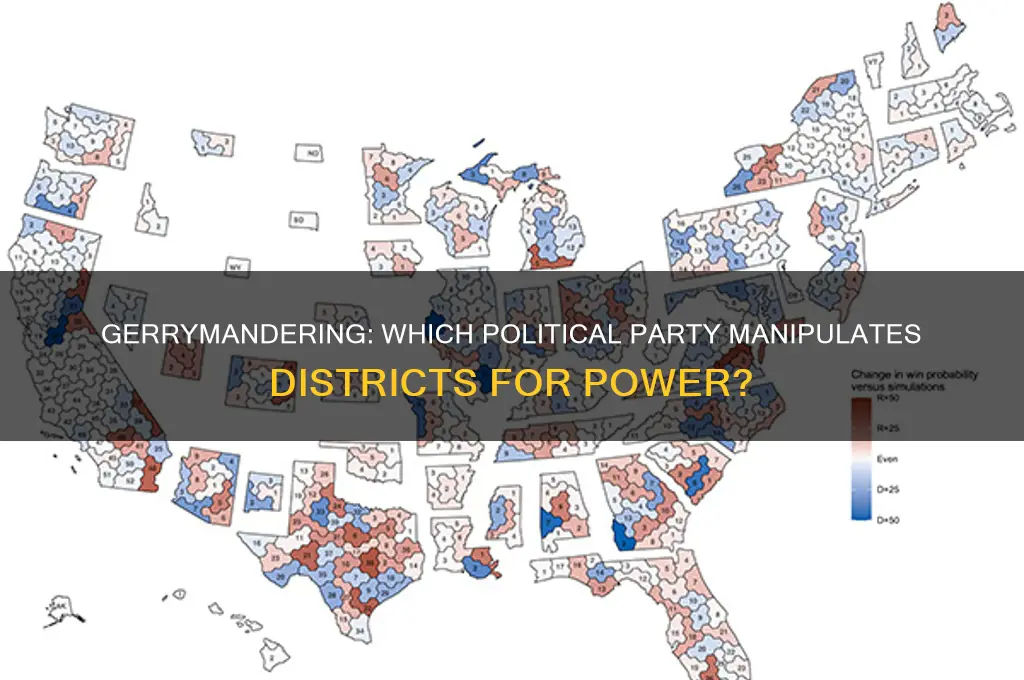

Impact of gerrymandering on election outcomes

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has a profound and measurable impact on election outcomes. By strategically clustering or dispersing voters based on their political leanings, parties can secure more seats than their overall vote share would otherwise warrant. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. House elections, Democrats won 1.4 million more votes nationwide than Republicans but still secured 33 fewer seats due to Republican-drawn district maps in key states like Pennsylvania and Michigan. This disparity illustrates how gerrymandering can distort democratic representation, amplifying one party’s power while marginalizing the other.

To understand the mechanics, consider a hypothetical state with 100 voters, 55 of whom support Party A and 45 Party B. If districts are drawn fairly, Party A might win 5 or 6 out of 10 seats, reflecting their slight majority. However, through gerrymandering, Party A could pack Party B voters into a few districts, ensuring overwhelming victories there, while spreading their own voters across the remaining districts to secure narrow wins. The result? Party A wins 7 or 8 seats, despite their modest vote advantage. This tactic, known as "cracking and packing," is a cornerstone of gerrymandering and has been employed by both major U.S. parties, though Republicans have been more aggressive in recent decades due to their control of state legislatures during redistricting cycles.

The impact of gerrymandering extends beyond individual elections, shaping the ideological tilt of legislative bodies and policy outcomes. In states like North Carolina and Wisconsin, Republican-drawn maps have entrenched GOP majorities in state legislatures and congressional delegations, even as Democratic candidates consistently win a majority of the statewide vote. This imbalance undermines the principle of "one person, one vote," as voters in gerrymandered districts effectively have less say in electing their representatives. Moreover, it stifles political competition, as incumbents in safe districts face little incentive to moderate their positions or engage with constituents, knowing their reelection is virtually assured.

Combating gerrymandering requires structural reforms, such as independent redistricting commissions, which have been adopted in states like California and Arizona. These bodies remove map-drawing authority from self-interested legislators, prioritizing compact, contiguous districts that reflect natural communities. Additionally, judicial intervention has played a role, with courts striking down egregiously gerrymandered maps in cases like *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), though the Supreme Court has declined to set a federal standard for partisan gerrymandering claims. Voters themselves can also drive change through ballot initiatives, as seen in Michigan and Colorado, where citizens successfully pushed for fairer redistricting processes.

Ultimately, the impact of gerrymandering on election outcomes is a stark reminder of the fragility of democratic systems. While both parties have engaged in this practice, its prevalence in recent years has disproportionately benefited Republicans, raising questions about the legitimacy of their legislative majorities. Addressing gerrymandering is not just a matter of political fairness but a necessary step toward restoring trust in electoral institutions and ensuring that every vote counts equally. Without meaningful reforms, the distortion of election results will continue to undermine the democratic ideals upon which the U.S. was founded.

The Perils of Political Activism: Risks, Repression, and Resilience

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal challenges against partisan gerrymandering

Partisan gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district lines to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. Both major parties have engaged in this tactic, but legal challenges have increasingly sought to curb its impact. These challenges often hinge on constitutional arguments, statistical evidence, and evolving judicial standards. The Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* held that federal courts cannot adjudicate partisan gerrymandering claims, leaving the issue to state courts and legislatures. However, this hasn’t stopped advocates from pursuing creative legal strategies to challenge egregious cases.

One key approach in legal challenges involves demonstrating intentional discrimination through statistical analysis. Plaintiffs often use metrics like the efficiency gap, which measures the disparity in wasted votes between parties, to prove that district maps were drawn with partisan intent. For example, in *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), Wisconsin’s Republican-drawn map was challenged using this method, though the case was ultimately dismissed on standing grounds. State courts have been more receptive to such arguments, as seen in Pennsylvania’s 2018 decision to strike down a Republican-gerrymandered map for violating the state constitution’s free and equal elections clause. This highlights the importance of leveraging state-level protections when federal avenues are limited.

Another strategy involves framing gerrymandering as a violation of voters’ rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. In *Common Cause v. Lewis* (2020), North Carolina’s Democratic voters argued that extreme partisan gerrymandering unconstitutionally burdened their right to representation. While federal courts remain hesitant to intervene, state constitutions often provide stronger grounds for such claims. For instance, North Carolina’s Supreme Court struck down a Republican-drawn map in 2022, citing violations of the state constitution’s equal protection clause. This underscores the need for plaintiffs to tailor their arguments to specific state constitutional provisions.

Practical tips for mounting successful legal challenges include building coalitions with nonpartisan groups, such as the League of Women Voters or the NAACP, to strengthen credibility and public support. Additionally, leveraging technology, like open-source mapping tools, can help plaintiffs present compelling visual evidence of gerrymandering. Finally, focusing on state-level litigation and ballot initiatives, as seen in Michigan and Colorado, where independent redistricting commissions were established, offers a viable path forward. While federal courts may remain reluctant to act, state-level victories demonstrate that legal challenges can still reshape the gerrymandering landscape.

Keynesian Economics: Which Political Party Champions This Economic Theory?

You may want to see also

Role of state legislatures in redistricting

State legislatures wield significant power in the redistricting process, a decennial task that reshapes electoral boundaries to reflect population changes. This authority, granted by Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, allows state lawmakers to redraw congressional and state legislative districts. While this responsibility is ostensibly about ensuring equal representation, it often becomes a tool for political manipulation, with both major parties engaging in gerrymandering to secure electoral advantages. The party in control of the state legislature at the time of redistricting typically dictates the outcome, drawing maps that favor their candidates and dilute the influence of opposing voters.

Consider the mechanics of this process. After the Census releases population data, state legislatures begin the intricate work of redistricting. They must adhere to criteria like equal population size per district and compliance with the Voting Rights Act, but beyond these constraints, creativity—or manipulation—flourishes. For instance, a party might "pack" opposition voters into a single district, minimizing their impact elsewhere, or "crack" them across multiple districts to dilute their voting power. The 2020 redistricting cycle saw Republicans controlling more state legislatures, leading to accusations of aggressive gerrymandering in states like Texas and North Carolina. Democrats, though less dominant, were not immune to the practice, as seen in Illinois and New York.

The consequences of this partisan control are profound. Gerrymandered maps can entrench political majorities, stifle competition, and distort representation. For example, in 2019, North Carolina’s state supreme court struck down a Republican-drawn map for being an "unconstitutional gerrymander," highlighting how extreme manipulation can undermine democratic principles. Conversely, in states like California, where an independent commission handles redistricting, maps tend to reflect demographic realities more accurately, fostering competitive elections. This contrast underscores the critical role state legislatures play—and the potential for abuse when partisan interests drive the process.

To mitigate these issues, reformers advocate for independent or bipartisan redistricting commissions. Currently, 15 states use such bodies to varying degrees, removing direct legislative control. For instance, Michigan’s 2018 ballot initiative created an independent commission, leading to fairer maps in 2020. However, transitioning to these models requires overcoming political resistance, as legislators are reluctant to surrender power. Until then, the redistricting process remains a high-stakes game of political chess, where state legislatures are both players and rulemakers.

In practical terms, citizens can engage by monitoring their state legislature’s redistricting efforts, attending public hearings, and advocating for transparency. Tools like online mapping software allow voters to propose alternative district lines, challenging partisan gerrymanders. While the fight against manipulation is ongoing, understanding the role of state legislatures in redistricting is the first step toward demanding a fairer, more representative system.

The Progressive Party's Rise: 1912's Third-Party Political Revolution Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both major political parties, Democrats and Republicans, have engaged in gerrymandering, though the extent varies by state and election cycle. Historically, the party in control of state legislatures during redistricting periods is more likely to manipulate district boundaries to favor their candidates.

There is no definitive answer, as both parties have been accused of gerrymandering. Republicans have been criticized for aggressive redistricting in states like Texas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, while Democrats have faced scrutiny in states like Maryland and Illinois.

Gerrymandering is a partisan issue, but both parties participate in it when they have the opportunity. The degree of gerrymandering often depends on which party controls the redistricting process in a given state.

No, gerrymandering cannot be attributed to one party nationwide. It is a localized issue, with the guilty party varying by state based on which party holds power during the redistricting process.