The question of which political party has obstructed the most is a contentious and complex issue, often fueled by partisan narratives and selective interpretations of legislative history. Obstruction, whether through filibusters, procedural delays, or outright opposition, is a tactic employed by both major parties in the United States, depending on their position in power. Democrats and Republicans alike have pointed fingers at one another, accusing the other side of gridlocking government to advance their agendas or block progress. Historically, the use of the filibuster in the Senate has been a significant tool for obstruction, with both parties leveraging it when in the minority to stall legislation. However, quantifying which party has obstructed the most is challenging, as it depends on the timeframe, context, and specific metrics used. Ultimately, the perception of obstruction often aligns with one’s political leanings, making it a deeply polarized and subjective debate.

Explore related products

$12.42 $27.99

What You'll Learn

- Historical Obstructionism: Analyzing long-term patterns of filibusters, vetoes, and legislative delays by major parties

- Senate Tactics: Examining the use of procedural tools like holds and cloture by parties

- Presidential Vetoes: Comparing veto rates and impacts across party-affiliated presidents

- Judicial Nominations: Assessing party-led blockades of Supreme Court and federal judge appointments

- Budget Impasses: Investigating party roles in government shutdowns and debt ceiling crises

Historical Obstructionism: Analyzing long-term patterns of filibusters, vetoes, and legislative delays by major parties

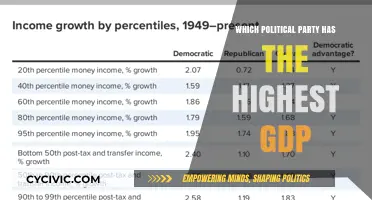

The filibuster, a procedural tactic allowing a minority to delay or block legislation, has been a cornerstone of legislative obstruction in the United States Senate. Historically, both major parties have employed this tool, but the frequency and impact of its use have shifted dramatically over time. In the early 20th century, filibusters were relatively rare, reserved for issues of profound national significance. However, since the 1970s, their use has skyrocketed, becoming a routine part of legislative maneuvering. Data from the Senate Historical Office reveals that the number of cloture motions—a procedural move to end a filibuster—has increased from an average of 8 per Congress in the 1960s to over 150 per Congress in recent decades. This trend underscores a broader normalization of obstructionism, raising questions about its long-term effects on governance.

Vetoes, another powerful tool of obstruction, offer a different lens through which to analyze partisan tactics. Presidents from both parties have used veto power to block legislation, but the context and frequency vary. For instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, vetoed 635 bills during his presidency, often to protect New Deal programs. In contrast, Barack Obama, also a Democrat, issued only 12 vetoes, reflecting a Congress dominated by Republican opposition. On the Republican side, George W. Bush vetoed 12 bills, while Ronald Reagan vetoed 78, many aimed at curbing Democratic spending initiatives. These numbers highlight how vetoes are not just a reflection of presidential ideology but also a strategic response to congressional dynamics. Analyzing veto patterns reveals how presidents adapt their obstructionist tactics based on the political landscape.

Legislative delays, often less visible than filibusters or vetoes, are equally significant in the history of obstructionism. Committees, controlled by the majority party, can indefinitely stall bills by refusing to schedule hearings or markups. This tactic has been employed by both parties to bury legislation they oppose. For example, during the Obama administration, Republican-controlled committees in the House systematically delayed or blocked bills on climate change, immigration, and healthcare. Similarly, during the Trump administration, Democratic-controlled House committees slowed the advancement of conservative priorities. Such delays are harder to quantify than filibusters or vetoes but are no less impactful, as they effectively kill bills without public debate or votes.

Comparing these obstructionist tactics across parties reveals a nuanced picture. While both Democrats and Republicans have used filibusters, vetoes, and legislative delays, the context and rationale often differ. Democrats have historically employed filibusters to protect civil rights and social welfare programs, as seen in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which faced a 75-day filibuster led by Southern Democrats. Republicans, on the other hand, have increasingly used the filibuster to block expansive government programs and regulatory measures, as evidenced by their opposition to the Affordable Care Act and climate legislation. Vetoes and legislative delays similarly reflect partisan priorities, with each party leveraging these tools to safeguard their core agendas.

To understand which party has obstructed the most, one must consider not just the frequency of these tactics but their impact on policy outcomes. For instance, while Republicans have used the filibuster more frequently in recent decades, Democrats have successfully passed transformative legislation like the Civil Rights Act and the Affordable Care Act despite significant obstruction. Conversely, Republican obstruction has effectively blocked major Democratic initiatives, such as gun control and immigration reform. Ultimately, the question of which party has obstructed the most depends on the metric used: raw numbers, legislative impact, or historical context. What is clear, however, is that obstructionism has become a defining feature of American politics, with both parties wielding these tools to advance their agendas and stymie their opponents.

Empowering Smaller Parties: Exploring Fairer Voting Systems for Diverse Representation

You may want to see also

Senate Tactics: Examining the use of procedural tools like holds and cloture by parties

The U.S. Senate, often referred to as the world's greatest deliberative body, has increasingly become a battleground where procedural tools like holds and cloture motions are wielded as weapons of obstruction. These tactics, while rooted in the Senate's rules, have been exploited by both parties to stall legislation, nominations, and other business. Understanding how and why these tools are used is critical to identifying which party has historically obstructed the most.

Step 1: Understand the Tools

A *hold* is an informal Senate practice allowing a senator to anonymously prevent a motion from reaching the floor, effectively freezing a bill or nomination. *Cloture*, on the other hand, is a procedural motion to end debate, requiring 60 votes to invoke. These tools are not inherently obstructive—they were designed to ensure thorough deliberation and protect the minority party. However, their misuse has transformed them into instruments of gridlock. For instance, in the 111th Congress (2009–2011), Republicans set a record by filing 137 cloture motions, reflecting a surge in obstructionist tactics.

Step 2: Analyze Historical Trends

Data from the Senate reveals a clear pattern: the party out of power tends to use these tools more aggressively. During the Obama administration, Republicans frequently employed holds and cloture motions to block judicial and executive nominations, culminating in the 2013 "nuclear option" when Democrats eliminated the filibuster for most nominations. Conversely, during the Trump administration, Democrats used holds to delay confirmations, though not at the same scale as their Republican counterparts in previous years. This suggests obstruction is often a reaction to political opposition rather than a consistent strategy.

Caution: Context Matters

While raw numbers can indicate obstruction, they don’t tell the whole story. For example, the increased use of holds in recent decades coincides with the erosion of bipartisanship and the rise of polarization. Additionally, some obstruction is justified—senators may use holds to demand amendments or transparency. Critics argue, however, that the frequency and scale of these tactics have undermined the Senate's ability to function effectively.

Takeaway: A Shifting Landscape

The party that has obstructed the most varies by era and context, but the trend is undeniable: procedural tools are increasingly used to stall rather than deliberate. Both parties share blame, though Republicans have set records in recent decades. As polarization deepens, these tactics will likely persist, raising questions about the Senate's future as a legislative body. To restore functionality, reforms such as limiting holds or lowering the cloture threshold may be necessary, though such changes would require bipartisan cooperation—a rarity in today’s Senate.

Understanding Representative Politics: Democracy's Core Mechanism Explained Simply

You may want to see also

Presidential Vetoes: Comparing veto rates and impacts across party-affiliated presidents

The power of the presidential veto is a critical tool in the American political system, allowing the executive branch to check the legislative branch. When examining which political party has obstructed the most, a natural starting point is to compare veto rates and impacts across party-affiliated presidents. Historical data reveals that both Democratic and Republican presidents have wielded the veto power, but the frequency, context, and consequences of these vetoes vary significantly. For instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, holds the record for the most vetoes at 635, many of which were tied to shaping New Deal legislation. In contrast, Republican presidents like George W. Bush and Donald Trump used vetoes more sparingly, often to block legislation perceived as overreaching or misaligned with conservative principles.

Analyzing these patterns, it becomes clear that veto rates alone do not tell the full story of obstruction. The impact of a veto depends on its timing, the political climate, and the president’s ability to rally public or congressional support. For example, Bill Clinton’s veto of a Republican-backed welfare reform bill in 1995 forced a compromise that ultimately reshaped social policy. Conversely, Barack Obama’s veto of the Keystone XL pipeline bill in 2015 was overridden by Congress, highlighting the limits of presidential power when facing a united opposition. These examples underscore that obstruction is not merely about quantity but about strategic deployment and political leverage.

To compare party-affiliated presidents effectively, consider the following steps: First, examine the legislative context in which vetoes occurred. Were they used to block partisan bills, protect constitutional principles, or advance specific policy agendas? Second, assess the outcomes of these vetoes. Did they lead to legislative stalemate, compromise, or override? Third, evaluate the long-term impact on governance. Did the vetoes strengthen or weaken the president’s party? For instance, Ronald Reagan’s vetoes often reinforced his conservative agenda, while Jimmy Carter’s frequent use of the pocket veto reflected his struggles with a divided Congress.

A cautionary note: equating vetoes with obstruction oversimplifies the complexities of presidential power. Vetoes can be a necessary tool for balancing power, not merely a mechanism for delay or defiance. For practical analysis, focus on the *why* and *how* of vetoes rather than the *how many*. For example, a president vetoing a bill to protect minority rights differs fundamentally from one blocking legislation for partisan gain. This distinction is crucial for understanding whether a party’s obstruction is principled or purely political.

In conclusion, comparing presidential vetoes across party lines requires a nuanced approach. While Democrats like Roosevelt and Clinton have used vetoes extensively, Republicans like Reagan and Bush have employed them selectively but effectively. The true measure of obstruction lies in the intent, impact, and legacy of these actions. By examining vetoes through this lens, we gain a clearer picture of which party has obstructed the most—not in sheer numbers, but in strategic influence and lasting consequences.

Is the BBC Biased? Uncovering the Political Leanings of the BBC

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Judicial Nominations: Assessing party-led blockades of Supreme Court and federal judge appointments

The confirmation of Supreme Court and federal judges has become a battleground for partisan politics, with both major parties employing obstruction tactics to shape the judiciary. A review of recent history reveals a pattern of escalating blockades, each side accusing the other of unprecedented obstruction. The question isn’t just about which party has obstructed more, but how these tactics have evolved and their long-term impact on judicial appointments.

Consider the filibuster’s role in judicial nominations. Until 2013, Senate rules required 60 votes to end debate on nominees, allowing the minority party to block appointments. Democrats, under Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, invoked the "nuclear option," eliminating the filibuster for most judicial nominees. Republicans, led by Mitch McConnell, later extended this to Supreme Court nominees in 2017 to confirm Neil Gorsuch. This escalation illustrates how procedural tools once used sparingly have become standard weapons in partisan warfare.

Supreme Court nominations offer stark examples of party-led blockades. Merrick Garland’s 2016 nomination by President Obama was blocked by Senate Republicans, who refused to hold hearings, citing the proximity to a presidential election. In contrast, Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation in 2020, just days before the election, highlighted the reversal of this rationale. These cases demonstrate how principles are often sacrificed for political expediency, eroding norms of fairness and consistency.

Federal judge appointments tell a similar story. During the Obama administration, Republicans slowed confirmations to a crawl, leaving a record number of vacancies. Democrats, in turn, have accused Republicans of rushing through Trump-era nominees with questionable qualifications. This tit-for-tat has created a judiciary increasingly polarized along partisan lines, raising concerns about its legitimacy and independence.

To assess which party has obstructed more, one must consider both quantity and impact. While Republicans have blocked more nominees in recent decades, Democrats’ use of the nuclear option fundamentally altered the rules of engagement. The takeaway? Both parties bear responsibility for the current state of judicial nominations, and neither can claim the moral high ground. The real loser is the American public, which deserves a judiciary free from partisan manipulation.

Do Political Parties Elect Legislation? Understanding the Role of Parties in Lawmaking

You may want to see also

Budget Impasses: Investigating party roles in government shutdowns and debt ceiling crises

Government shutdowns and debt ceiling crises are not mere bureaucratic hiccups; they are high-stakes showdowns with real consequences for the economy and public trust. Since 1976, the U.S. has experienced 22 funding gaps, with 10 escalating into full shutdowns. While both parties have played roles in these impasses, a closer examination reveals recurring patterns. For instance, the 2013 shutdown, triggered by a Republican-led House demanding changes to the Affordable Care Act, lasted 16 days and cost the economy an estimated $24 billion. Similarly, the 1995-1996 shutdown, under a Republican Congress and Democratic President Clinton, lasted 21 days, highlighting how partisan gridlock often centers on budget priorities and ideological divides.

To understand party roles, consider the debt ceiling crisis, a separate but related issue. Since 2011, Republicans have consistently used the debt ceiling as leverage to extract spending cuts, arguing it forces fiscal responsibility. Democrats, in contrast, frame such tactics as reckless, pointing to the 2011 crisis that led to the first-ever U.S. credit rating downgrade. While both parties have voted against raising the debt ceiling in the past, Republicans have more frequently tied it to policy demands, creating a pattern of brinkmanship. For example, in 2013, House Republicans demanded defunding Obamacare as a condition for raising the debt limit, a move Democrats deemed hostage-taking.

Analyzing these impasses requires distinguishing between obstruction and principled opposition. Obstruction implies deliberate delay or blockage without a genuine attempt at compromise. In shutdowns, the party refusing to pass a budget or continuing resolution often bears more responsibility, as they effectively halt government operations. However, context matters. For instance, the 2018-2019 shutdown, the longest in U.S. history, occurred when President Trump demanded $5.7 billion for a border wall, a policy Democrats staunchly opposed. Here, both sides claimed the other was obstructing, but the trigger was a specific, non-negotiable demand from the executive branch.

Practical takeaways for policymakers and citizens include recognizing the asymmetry in consequences. Shutdowns disproportionately harm federal workers, contractors, and vulnerable populations reliant on government services. Debt ceiling crises threaten global financial stability, as defaulting on U.S. debt would have catastrophic ripple effects. To mitigate future impasses, Congress could adopt automatic continuing resolutions or remove the debt ceiling altogether, as it serves no functional purpose beyond political leverage. Voters, meanwhile, should scrutinize candidates’ records on budget negotiations, prioritizing those who prioritize governance over ideological purity.

In conclusion, while both parties share blame for budget impasses, historical data and case studies suggest Republicans have more frequently employed obstructionist tactics in recent decades, particularly around shutdowns and debt ceiling crises. This isn’t to absolve Democrats of responsibility but to highlight recurring patterns. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for addressing systemic issues in budget negotiations and fostering a more functional government. After all, in a democracy, the ability to govern effectively is as important as the principles one fights for.

Understanding Third Party Political Organizations: Roles, Impact, and Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Studies and analyses often point to the Republican Party as having engaged in more obstructionist tactics, particularly through the use of filibusters and procedural delays, especially since the early 2000s.

Obstruction is typically measured by tactics like filibusters, procedural votes, and refusals to cooperate on legislation, with data often sourced from congressional records and political science research.

Yes, the Democratic Party has also been accused of obstruction, particularly during periods of Republican presidential administrations, such as during the George W. Bush and Donald Trump presidencies.

The filibuster is a key tool for obstruction, allowing a minority party to block or delay legislation by requiring a supermajority (60 votes in the Senate) to proceed, often leading to gridlock.

Yes, in parliamentary systems, opposition parties often use tactics like no-confidence votes or prolonged debates to obstruct the ruling party’s agenda, as seen in countries like the UK and India.

![Gridlock'd [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71QACfSTh3L._AC_UY218_.jpg)