The question of which political party has historically controlled Congress is a central aspect of understanding American political dynamics. Since the founding of the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties have dominated congressional leadership, with periods of control shifting between them based on electoral outcomes, societal changes, and policy priorities. Historically, the Democratic Party held significant majorities in both the House and Senate for much of the 20th century, particularly during the New Deal and Great Society eras. However, the Republican Party has also experienced extended periods of control, notably during the Reagan era and more recently in the early 21st century. These shifts reflect broader ideological and demographic trends, as well as the parties' ability to adapt to the evolving needs and preferences of the American electorate. Analyzing this historical control provides valuable insights into the balance of power, legislative achievements, and the ongoing struggle for political dominance in the United States.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Democratic Control of Congress

The Democratic Party has historically held control of Congress for significant periods, particularly during the 20th century. From 1932 to 1994, Democrats maintained a majority in the House of Representatives for all but four years, a dominance largely attributed to the New Deal coalition forged under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This coalition, comprising labor unions, urban voters, ethnic minorities, and Southern conservatives, solidified Democratic control and enabled the passage of landmark legislation like the Social Security Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

To understand the mechanics of Democratic control, consider the Senate, where the party’s majority has often hinged on narrow margins. For instance, during the 117th Congress (2021–2023), Democrats held a 50-50 tie with Republicans, with Vice President Kamala Harris casting tie-breaking votes. This razor-thin majority highlights the fragility of control and the importance of strategic coalition-building within the party. Practical tip: Tracking Senate elections in swing states like Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Arizona can provide early indicators of potential shifts in Democratic control.

A comparative analysis reveals that Democratic control of Congress has often coincided with periods of progressive policy advancement. For example, the 111th Congress (2009–2011), with a Democratic majority in both chambers, passed the Affordable Care Act, a transformative healthcare reform. In contrast, Republican-controlled Congresses have tended to prioritize tax cuts and deregulation. This pattern underscores the ideological differences in legislative priorities and the impact of party control on policy outcomes.

Maintaining Democratic control requires addressing demographic and geographic challenges. While Democrats excel in urban and suburban areas, they struggle in rural districts, where Republican support remains strong. To counterbalance this, the party has increasingly focused on mobilizing young voters, who lean Democratic by a 2:1 margin, and engaging minority communities. Dosage value: In the 2020 election, voters under 30 supported Democratic House candidates by 65%, compared to 39% among voters over 65.

Finally, historical trends suggest that Democratic control of Congress is often reactive to Republican presidencies. For instance, Democrats gained control of both chambers in 2006 as a backlash to President George W. Bush’s handling of the Iraq War and Hurricane Katrina. Similarly, the 2018 midterms saw Democrats retake the House amid opposition to President Donald Trump’s policies. This reactive dynamic highlights the cyclical nature of congressional control and the role of voter sentiment in shifting majorities. Practical tip: Monitoring presidential approval ratings can provide insights into potential congressional power shifts in upcoming elections.

New York's Political Landscape: Which Party Dominates the Empire State?

You may want to see also

Republican Dominance in Senate

The Republican Party has maintained a notable dominance in the Senate during specific periods, particularly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. From 1981 to 1987, and again from 1995 to 2001, Republicans held the majority, shaping key legislative agendas. This control was further solidified between 2015 and 2021, with a brief interruption in 2019–2020. These periods highlight the party’s strategic effectiveness in securing and retaining Senate seats, often leveraging regional strongholds in the South and Midwest.

Analyzing the reasons behind this dominance reveals a combination of demographic trends and political strategies. Republicans have historically performed well in rural and suburban areas, which are overrepresented in the Senate due to its structure. Each state, regardless of population size, has two senators, giving less populous, Republican-leaning states disproportionate influence. Additionally, the party’s focus on issues like fiscal conservatism and states’ rights resonates strongly in these regions, solidifying voter loyalty.

To understand the practical implications, consider the legislative outcomes during Republican-controlled Senates. For instance, the 1996 welfare reform bill and the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act were both passed under Republican majorities, reflecting the party’s policy priorities. These examples demonstrate how Senate dominance translates into tangible policy changes, often with long-term effects on the economy and social programs.

For those interested in political strategy, studying Republican Senate campaigns offers valuable insights. The party has consistently targeted competitive races in swing states, investing heavily in grassroots mobilization and digital advertising. A practical tip for campaigns: focus on local issues and tailor messaging to regional concerns, as Republicans have done effectively in states like Ohio and Florida.

In conclusion, Republican dominance in the Senate is not merely a historical footnote but a recurring pattern with significant implications. By understanding the demographic, structural, and strategic factors at play, observers can better predict future political dynamics and the potential direction of federal legislation. This analysis underscores the importance of the Senate in American politics and the Republican Party’s ability to capitalize on its unique features.

Steve Scully's Political Party Affiliation: Uncovering His Ideological Leanings

You may want to see also

Historical Shifts in House Majority

The House of Representatives has witnessed numerous shifts in party control throughout its history, reflecting the dynamic nature of American politics. One notable trend is the pendulum-like swing between Democratic and Republican majorities, often influenced by economic conditions, social issues, and presidential popularity. For instance, the Democratic Party dominated the House for much of the 20th century, holding the majority from 1931 to 1995, with only brief interruptions. This era coincided with significant legislative achievements, such as the New Deal and the Great Society programs, which solidified Democratic control by appealing to a broad coalition of voters.

Analyzing these shifts reveals the impact of external events on congressional elections. The 1994 midterms, for example, marked a dramatic shift when Republicans gained 54 seats, securing their first House majority in 40 years. This "Republican Revolution," led by Newt Gingrich, was fueled by voter dissatisfaction with Democratic policies and a focus on fiscal conservatism and smaller government. Similarly, the 2006 midterms saw Democrats regain control, capitalizing on public discontent with the Iraq War and Republican scandals. These examples illustrate how national issues and voter sentiment can swiftly alter the balance of power in the House.

To understand the mechanics of these shifts, consider the role of redistricting and demographic changes. Redistricting, often controlled by state legislatures, can favor one party by gerrymandering districts. For instance, after the 2010 census, Republican-controlled states redrew maps that helped maintain their House majority for several cycles. Conversely, demographic shifts, such as urbanization and changing voter preferences, can undermine these efforts. The rise of suburban voters leaning Democratic in recent years has contributed to the party's gains in traditionally Republican districts, demonstrating how long-term trends can gradually erode one party's dominance.

A persuasive argument can be made that presidential elections often set the stage for House majority shifts. Midterm elections, in particular, frequently serve as a referendum on the sitting president's performance. Since World War II, the president's party has lost an average of 26 House seats in midterms, a phenomenon known as the "midterm curse." This trend underscores the importance of presidential leadership and its downstream effects on congressional races. For voters, this means that holding the president accountable through midterm elections is a powerful tool to check their party's control in Congress.

In practical terms, tracking these historical shifts can help voters and analysts predict future trends. Key indicators include economic performance, presidential approval ratings, and the salience of social issues. For instance, the 2018 midterms saw Democrats gain 41 House seats, driven by opposition to President Trump and concerns over healthcare policy. To stay informed, follow polling data, economic reports, and legislative actions leading up to elections. Understanding these patterns not only enriches political knowledge but also empowers individuals to engage more effectively in the democratic process.

Funding Democracy: Strategies Political Parties Use to Raise Campaign Money

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Third-Party Influence on Congress

Historically, the Democratic and Republican parties have dominated control of Congress, but third parties have occasionally exerted significant influence, often by shaping debates, forcing major parties to adopt their policies, or acting as spoilers in elections. While third-party candidates rarely win congressional seats, their impact on the political landscape is measurable and strategic. For instance, the Progressive Party in the early 20th century pushed for labor rights and antitrust legislation, forcing both major parties to address these issues. Similarly, the Libertarian Party’s emphasis on limited government has nudged Republicans toward more fiscally conservative positions. These examples illustrate how third parties can drive policy shifts without holding office.

To understand third-party influence, consider their role in elections. Third-party candidates often siphon votes from major-party contenders, altering outcomes in close races. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential campaign, for example, drew votes primarily from Republicans, potentially costing George H.W. Bush reelection. In congressional races, this dynamic can weaken a major party’s grip on a district, indirectly influencing which party controls Congress. While third parties rarely win, their ability to disrupt electoral math makes them a force to be reckoned with, especially in polarized political climates.

Third parties also serve as incubators for ideas that later become mainstream. The Green Party’s focus on environmental sustainability, once considered fringe, has pushed Democrats to prioritize climate change legislation. Similarly, the Reform Party’s advocacy for campaign finance reform in the 1990s laid the groundwork for later bipartisan efforts. This process of idea adoption demonstrates how third parties can shape congressional agendas even when they lack representation. By championing specific issues, they create pressure for major parties to respond, effectively influencing policy direction.

However, third-party influence is not without challenges. The winner-take-all electoral system and stringent ballot access laws often marginalize third-party candidates, limiting their direct impact. To maximize influence, third parties must strategically target races where their presence can sway outcomes or force policy concessions. For instance, focusing on swing districts or aligning with grassroots movements can amplify their voice. Practical steps include coalition-building with like-minded groups, leveraging social media for outreach, and fielding candidates in local races to build credibility.

In conclusion, while third parties rarely control Congress, their influence is felt through electoral disruption, policy innovation, and issue advocacy. By understanding their strategic role, voters and policymakers can better appreciate how these parties shape the political discourse and, ultimately, the balance of power in Congress. Third parties may not dominate the legislative branch, but their impact on its direction is undeniable.

Public Opinion Power: How Political Parties Shape Policies and Campaigns

You may want to see also

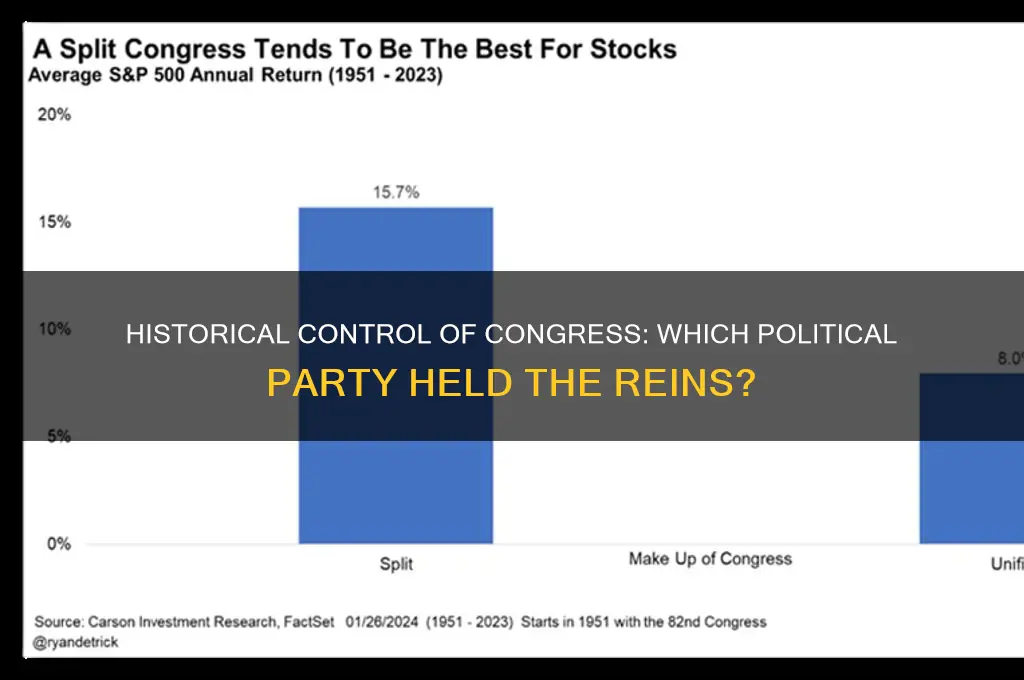

Post-War Congressional Party Trends

The post-war era in American politics has witnessed significant shifts in congressional control, with the Democratic Party dominating the House of Representatives for nearly 60 consecutive years following World War II. From 1955 to 1995, Democrats held the majority in the House, a streak that underscores the party's historical strength in congressional politics. This period, often referred to as the "Democratic era," was characterized by the implementation of landmark legislation, including the Civil Rights Act and the Great Society programs. However, the Senate exhibited more volatility, with control fluctuating between the two parties, reflecting the upper chamber's sensitivity to national political tides.

Analyzing these trends reveals the impact of presidential coattails and midterm elections on congressional control. During the post-war period, the party of the incumbent president often suffered losses in midterm elections, a phenomenon known as the "midterm curse." For instance, Republicans gained control of the Senate in 1980 following Ronald Reagan's presidential victory but lost it in 1986 during his second term. This pattern highlights the cyclical nature of congressional power and the challenges of maintaining unified government. To mitigate midterm losses, parties should focus on candidate recruitment, issue framing, and grassroots mobilization, particularly in competitive districts.

A comparative analysis of post-war congressional trends also reveals the role of redistricting in shaping party control. The 1994 Republican Revolution, which ended Democratic dominance in the House, was partly fueled by gerrymandering efforts in key states. Similarly, the 2010 Tea Party wave led to Republican gains and subsequent redistricting advantages. While redistricting is a legal process, its manipulation can distort representation and entrench partisan control. To address this, states should adopt independent redistricting commissions, as seen in California and Michigan, to ensure fairer maps and more competitive elections.

Persuasively, the post-war era demonstrates the importance of adaptability in maintaining congressional majorities. The Democratic Party's long-standing control of the House was not due to static strategies but rather its ability to evolve with changing demographics and policy priorities. For example, the party's shift from a predominantly Southern base to a more urban and suburban coalition allowed it to remain competitive. In contrast, the Republican Party's success in the late 20th century was tied to its appeal to conservative voters and its focus on economic issues. Parties seeking sustained congressional control must continually reassess their platforms, messaging, and outreach to reflect the needs and values of the electorate.

Finally, a descriptive examination of post-war trends highlights the increasing polarization of Congress. Since the 1970s, ideological sorting has led to more homogeneous party caucuses, with moderates becoming an endangered species. This polarization has been exacerbated by primary elections, where extreme candidates often outperform centrists. To foster bipartisanship and legislative productivity, Congress should consider reforms such as open primaries, ranked-choice voting, or the creation of a bipartisan problem-solving caucus. By encouraging collaboration across party lines, these measures can help break the gridlock that has defined much of the post-war congressional landscape.

Abortion Policies: How Political Parties Shape Reproductive Rights Debates

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party has historically controlled Congress for the longest periods, particularly in the House of Representatives, since its founding.

In recent decades, control of Congress has shifted between the Democratic and Republican Parties, with no single party dominating consistently.

The Democratic Party controlled Congress during the Great Depression, coinciding with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and the implementation of the New Deal.

Yes, the Republican Party held a long-standing majority in Congress during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the Senate, and regained control of both chambers in the 1990s and 2000s.