The question of which political party has borrowed most from social security is a contentious and complex issue, rooted in the financial mechanisms and policy decisions surrounding the Social Security Trust Fund. In the United States, both major political parties—the Democratic Party and the Republican Party—have, at various times, been accused of utilizing Social Security surpluses to fund other government programs, effectively borrowing from the fund. Historically, the federal government has issued special-issue Treasury bonds to the Trust Fund when payroll tax revenues exceeded benefit payouts, but these bonds represent an intra-governmental debt rather than external borrowing. Critics argue that this practice has undermined the long-term solvency of Social Security, as the funds are effectively redirected to cover general budget deficits. While both parties have supported policies that impact Social Security’s finances, the extent of borrowing and the responsibility for it remain subjects of partisan debate, with each side often pointing fingers at the other. Understanding the nuances of this issue requires examining legislative histories, budgetary practices, and the broader political context in which these decisions were made.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical borrowing trends of major political parties from social security funds

- Democratic Party’s reliance on social security surpluses for spending programs

- Republican Party’s use of social security funds for tax cuts

- Impact of borrowing on social security’s long-term financial sustainability

- Cross-party comparisons of social security borrowing and repayment strategies

Historical borrowing trends of major political parties from social security funds

The practice of borrowing from social security funds has been a contentious issue in American politics, with both major parties engaging in this fiscal maneuver at various points in history. A closer look at the data reveals a nuanced picture, where the extent and rationale for borrowing differ significantly between the Democratic and Republican parties. For instance, during the Reagan administration, the federal government borrowed heavily from the Social Security Trust Fund to finance tax cuts and increase defense spending, a move that set a precedent for future administrations.

To understand the historical borrowing trends, it's essential to examine the legislative actions and economic contexts that facilitated these transactions. The Social Security Act of 1935 established the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which began collecting payroll taxes in 1937. However, it wasn't until the 1980s that large-scale borrowing from this fund became a common practice. The Greenspan Commission, appointed by President Reagan, recommended a series of changes to Social Security, including the advance funding of the program through increased payroll taxes. This resulted in a surplus of funds, which the government subsequently borrowed to offset deficits in the general fund.

A comparative analysis of borrowing patterns reveals that Republican administrations have historically borrowed more from social security funds than their Democratic counterparts. For example, during the George W. Bush administration, the government borrowed approximately $1.4 trillion from the Social Security Trust Fund to finance tax cuts and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In contrast, the Obama administration borrowed around $300 billion, primarily to stimulate the economy during the Great Recession. These figures highlight the differing fiscal priorities and economic philosophies of the two parties.

When evaluating the implications of borrowing from social security funds, it's crucial to consider the long-term consequences for the program's solvency. While borrowing can provide temporary relief for budget shortfalls, it also reduces the funds available for future Social Security beneficiaries. To mitigate this risk, policymakers should consider implementing safeguards, such as: (1) establishing a separate budget for Social Security, (2) imposing penalties for excessive borrowing, and (3) requiring congressional approval for any borrowing from the Trust Fund. By adopting these measures, lawmakers can ensure the sustainability of Social Security while still addressing pressing fiscal challenges.

In recent years, the issue of borrowing from social security funds has gained renewed attention, particularly in light of the program's projected insolvency in 2034. As policymakers debate potential solutions, including benefit cuts, tax increases, and further borrowing, it's essential to learn from historical trends. A comprehensive understanding of past borrowing patterns can inform more effective and equitable policy decisions, ensuring the long-term viability of Social Security for future generations. By examining the specific actions and rationales of each administration, we can develop a more nuanced approach to fiscal policy, one that balances the needs of the present with the obligations of the future.

Why Join a Political Party? Exploring Purpose and Impact

You may want to see also

Democratic Party’s reliance on social security surpluses for spending programs

The Democratic Party has historically leveraged Social Security surpluses to fund ambitious spending programs, a strategy that reflects both its policy priorities and fiscal pragmatism. Since the 1980s, when Social Security began running annual surpluses, these excess funds have been deposited into the Social Security Trust Fund and invested in U.S. Treasury bonds. This mechanism effectively allows the federal government to borrow from Social Security to finance other expenditures. Democrats, in particular, have championed this approach to support initiatives like healthcare expansion, education, and infrastructure, arguing that these investments benefit the broader population, including Social Security recipients.

Consider the mechanics of this process: When Social Security collects more in payroll taxes than it pays out in benefits, the surplus is used to purchase Treasury bonds, which are then spent on federal programs. This intergovernmental borrowing has enabled Democrats to advance their agenda without directly raising taxes or cutting other programs. For instance, during the Obama administration, Social Security surpluses helped fund the Affordable Care Act, which expanded healthcare access to millions of Americans. Critics argue this practice undermines the financial stability of Social Security, but proponents counter that it ensures the program’s surpluses are reinvested in societal well-being rather than left idle.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both parties have utilized Social Security surpluses, Democrats have done so more systematically to fund progressive initiatives. Republicans, by contrast, have often prioritized tax cuts and defense spending, sometimes at the expense of domestic programs. For example, the George W. Bush administration’s tax cuts and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were partially financed through borrowing from Social Security, but these expenditures did not align with the safety net expansion Democrats typically pursue. This divergence highlights the Democratic Party’s unique reliance on Social Security surpluses as a tool for advancing its policy goals.

Practical implications of this strategy are significant. By redirecting Social Security surpluses, Democrats have been able to address pressing societal needs without exacerbating budget deficits in the short term. However, this approach carries long-term risks, as it accelerates the depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund. For individuals aged 50 and older, this raises concerns about the program’s solvency when they retire. To mitigate these risks, policymakers could explore reforms such as raising the payroll tax cap or adjusting benefit formulas, ensuring Social Security remains viable while continuing to fund critical programs.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party’s reliance on Social Security surpluses for spending programs reflects a strategic use of fiscal resources to advance progressive priorities. While this approach has enabled significant investments in healthcare, education, and infrastructure, it also underscores the need for sustainable reforms to safeguard Social Security’s future. Balancing immediate policy goals with long-term financial stability remains a critical challenge for Democrats as they navigate this complex fiscal landscape.

Party Politics: Impact on Congressional Efficiency and Governance

You may want to see also

Republican Party’s use of social security funds for tax cuts

The Republican Party has historically advocated for tax cuts as a cornerstone of its economic policy, often prioritizing them over the long-term solvency of social security. While social security is funded through payroll taxes and intended to be a self-sustaining program, its surplus has been a tempting target for politicians seeking to finance other priorities. Since the 1980s, Republican administrations have repeatedly pushed for tax cuts, particularly for high-income earners and corporations, which have contributed to growing federal deficits. To offset these deficits, funds from the social security trust fund have been used, effectively borrowing from future retirees to finance current tax reductions. This practice raises concerns about the sustainability of social security and the fairness of shifting the burden of tax cuts onto future generations.

Consider the mechanics of how this borrowing occurs. When the federal government runs a deficit, it issues Treasury bonds to cover the shortfall. The social security trust fund, which holds a surplus of payroll tax revenues, invests in these bonds, effectively lending money to the general fund. While these bonds are considered secure investments, they represent an intergovernmental debt that must be repaid with interest. When tax cuts reduce federal revenue, the government’s ability to repay this debt is compromised, increasing the risk that future social security benefits may be reduced or that payroll taxes will need to be raised. This dynamic highlights the trade-off between immediate tax relief and the long-term health of social security.

A persuasive argument can be made that this approach undermines the very purpose of social security. Established in 1935 as a safety net for retirees, disabled individuals, and survivors, social security relies on a pay-as-you-go system where current workers fund benefits for current retirees. By diverting funds to finance tax cuts, Republicans risk eroding public trust in the program and jeopardizing its ability to fulfill its mission. For example, the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts, which disproportionately benefited high-income earners, contributed to a significant increase in federal debt. While these cuts were touted as stimulative for the economy, their long-term impact on social security’s financial stability has been a point of contention. Critics argue that such policies prioritize short-term political gains over the welfare of future retirees.

Comparatively, the Democratic Party has generally taken a more protective stance toward social security, advocating for its preservation and expansion. However, the focus here is on the Republican Party’s specific use of social security funds for tax cuts, a strategy that has been both a policy choice and a political calculation. By framing tax cuts as a means to boost economic growth, Republicans appeal to their base, even if it means increasing reliance on social security’s surplus. This approach, while politically expedient, raises ethical questions about intergenerational equity. Are current taxpayers justified in enjoying lower taxes if it means future retirees face reduced benefits or higher payroll taxes?

In practical terms, understanding this issue requires examining the numbers. As of 2023, the social security trust fund holds approximately $2.9 trillion in assets, primarily in Treasury bonds. However, the program is projected to face a funding shortfall by 2034, after which it will only be able to pay about 77% of scheduled benefits. While multiple factors contribute to this shortfall, the repeated use of social security funds to finance tax cuts has played a role. For individuals planning for retirement, this uncertainty underscores the importance of diversifying income sources and staying informed about policy changes. Policymakers, meanwhile, must balance the desire for tax relief with the need to ensure social security’s long-term viability. The Republican Party’s approach to this balance remains a critical point of debate in discussions about fiscal responsibility and social welfare.

Understanding Vox's Political Bias: A Comprehensive Analysis and Evaluation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of borrowing on social security’s long-term financial sustainability

The practice of borrowing from Social Security has become a contentious issue, with significant implications for the program's long-term financial sustainability. Historically, both major political parties in the United States have engaged in this practice, albeit with varying degrees and rationales. However, the focus here is not on assigning blame but on understanding the consequences of such actions. When funds are diverted from Social Security, it creates a ripple effect that extends far beyond the immediate financial shortfall. The program's trust funds, which are intended to ensure benefits for future retirees, become depleted at an accelerated rate, raising concerns about the ability to meet obligations in the coming decades.

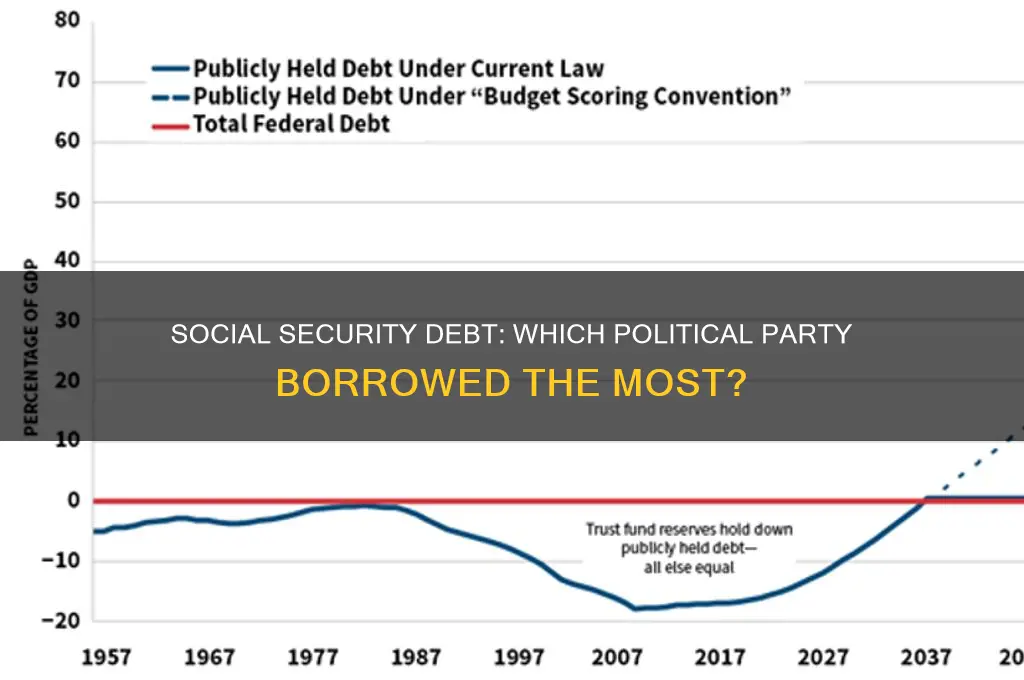

Consider the mechanics of Social Security funding: payroll taxes from current workers are meant to cover benefits for current retirees, with any surplus being invested in special Treasury bonds. Borrowing from these funds disrupts this delicate balance. For instance, if a political party authorizes the transfer of Social Security funds to cover general budget shortfalls, it effectively reduces the surplus available for investment. Over time, this diminishes the trust funds' ability to earn interest, which is crucial for their long-term solvency. By 2034, the Social Security Administration projects that the combined trust funds will be exhausted, leading to automatic benefit cuts unless Congress intervenes. Accelerated borrowing only hastens this timeline, exacerbating the financial strain on the program.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both parties have borrowed from Social Security, the scale and frequency of such actions have differed. For example, during periods of unified government control, one party may have had more opportunities to redirect funds. However, the impact of borrowing transcends partisan politics. Every dollar borrowed today is a dollar not available for future retirees, many of whom rely on Social Security as their primary source of income. For individuals aged 65 and older, Social Security constitutes approximately 33% of their total income. Reducing benefits due to financial shortfalls could force millions into poverty, particularly those without substantial savings or alternative retirement plans.

To mitigate the impact of borrowing on Social Security's sustainability, policymakers must adopt a multi-pronged approach. First, they should prioritize repaying any borrowed funds with interest to restore the trust funds' balance. Second, increasing the payroll tax cap—currently set at $160,200—could inject additional revenue into the system, ensuring its solvency for future generations. Finally, fostering bipartisan cooperation is essential to implement structural reforms that address the program's long-term funding challenges without resorting to short-term borrowing. By taking these steps, Congress can safeguard Social Security's financial health and fulfill its commitment to America's retirees.

In conclusion, borrowing from Social Security undermines the program's ability to provide a safety net for millions of Americans. While political parties may differ in their approaches to fiscal policy, the consequences of such actions are universally detrimental. By understanding the mechanics of Social Security funding and the real-world implications of borrowing, stakeholders can advocate for sustainable solutions that protect the program's long-term viability. The clock is ticking, and the choices made today will determine the security of retirees for generations to come.

Tracing the Roots: When Did Political Polarization Begin?

You may want to see also

Cross-party comparisons of social security borrowing and repayment strategies

The debate over which political party has borrowed most from social security often overshadows a more critical question: how do parties differ in their strategies for borrowing and repayment? A cross-party comparison reveals distinct approaches, each with implications for fiscal sustainability and societal trust. For instance, while Party A may justify borrowing as a temporary measure during economic downturns, Party B might frame it as a long-term investment in infrastructure, promising future returns. These rationales are not just ideological stances but practical blueprints that shape policy outcomes.

Analyzing repayment strategies uncovers further divergence. Party C, for example, advocates for gradual repayment through incremental tax increases, targeting high-income earners to minimize public backlash. In contrast, Party D proposes cutting non-essential government spending, a strategy that appeals to fiscal conservatives but risks undermining public services. Both approaches carry trade-offs: the former may stifle economic growth, while the latter could exacerbate inequality. Understanding these nuances is essential for voters who prioritize financial stability over partisan loyalty.

A comparative analysis of borrowing patterns highlights another layer of complexity. Party E has historically borrowed larger sums during crises, such as recessions or pandemics, but has also demonstrated a track record of timely repayment. Party F, however, borrows smaller amounts more frequently, often for politically popular initiatives like education or healthcare, but struggles with repayment due to inconsistent revenue streams. This pattern suggests that the scale of borrowing alone is not indicative of fiscal responsibility; the context and repayment plan matter equally.

Practical tips for evaluating these strategies include examining a party’s historical fiscal behavior, scrutinizing their proposed revenue sources, and assessing the transparency of their repayment plans. For instance, does a party’s budget outline specific timelines and mechanisms for repayment, or does it rely on vague promises of future economic growth? Voters should also consider the demographic impact of borrowing and repayment strategies. A policy that burdens younger generations with debt, for example, may be unsustainable in the long term, regardless of its short-term benefits.

In conclusion, cross-party comparisons of social security borrowing and repayment strategies reveal more than just partisan differences—they expose fundamental philosophies about governance and fiscal responsibility. By focusing on the specifics of how parties borrow and repay, voters can make informed decisions that align with their values and priorities. This analytical lens shifts the conversation from blame to accountability, fostering a more constructive dialogue about the future of social security.

Switching Political Parties in Rhode Island: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both Democratic and Republican administrations have borrowed from the Social Security Trust Fund, but the exact amounts vary by year and administration. Historically, the practice of borrowing from Social Security has been bipartisan.

The federal government borrows from the Social Security Trust Fund by issuing Treasury bonds. These bonds are essentially IOUs that the government promises to repay with interest when Social Security needs the funds.

There is no clear consensus on which party has borrowed more, as the practice has occurred under both Democratic and Republican leadership. The total amount borrowed depends on the fiscal policies and budget deficits of each administration.

Borrowing itself does not directly threaten Social Security's solvency, as the Trust Fund is legally obligated to be repaid. However, long-term solvency concerns arise from demographic changes, such as an aging population and fewer workers paying into the system.

The government is legally required to repay the Social Security Trust Fund. Defaulting on this debt would require a change in law and is highly unlikely, as it would undermine the credibility of U.S. Treasury securities globally.