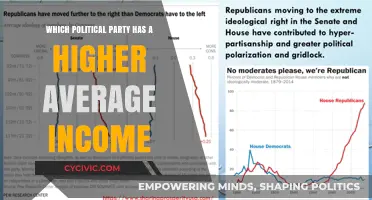

The question of which political party has overseen the worst economies in American history is a contentious and complex issue, often debated through partisan lenses. Economic performance is influenced by a myriad of factors, including global events, policy decisions, and unforeseen crises, making it difficult to attribute blame or credit solely to a political party. Critics of both major parties—Democrats and Republicans—point to specific periods of economic hardship under their respective administrations. For instance, the Great Depression occurred under Republican President Herbert Hoover, though the recovery efforts were largely associated with Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Similarly, the 2008 financial crisis unfolded under Republican President George W. Bush, while the subsequent recession and recovery efforts were managed under Democratic President Barack Obama. Ultimately, evaluating economic performance requires a nuanced understanding of historical context, policy impacts, and the broader global economic environment, rather than simplistic partisan blame.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Great Depression under Hoover's Republican administration: economic collapse, mass unemployment, bank failures

- s stagflation crisis: Carter's Democratic era marked by high inflation, slow growth

- financial crisis: Bush's Republican term saw housing collapse, bank bailouts

- Post-WWII recession: Truman's Democratic policies led to severe economic downturn in 1949

- Early 1800s Panic: Democratic-Republican Party faced economic chaos during the Panic of 1819

Great Depression under Hoover's Republican administration: economic collapse, mass unemployment, bank failures

The Great Depression, a cataclysmic economic downturn, remains one of the most devastating periods in American history. It began in 1929, during the Republican administration of President Herbert Hoover, and its effects were felt for over a decade. Hoover’s presidency became synonymous with economic collapse, mass unemployment, and widespread bank failures, raising questions about the role of his policies in exacerbating the crisis. While some argue that Hoover’s interventions were insufficient, others contend that his attempts to stabilize the economy were constrained by the era’s economic orthodoxy and the sheer scale of the disaster.

Consider the numbers: by 1933, unemployment had soared to 25%, leaving over 15 million Americans jobless. Industrial production plummeted by nearly 50%, and thousands of banks failed, erasing billions in savings. Hoover’s administration responded with measures like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which raised tariffs on imports, and the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide loans to banks and businesses. However, these efforts were widely criticized as too little, too late. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, in particular, is often cited as a policy blunder that deepened the global economic crisis by stifling international trade.

A closer analysis reveals that Hoover’s approach was rooted in a belief in limited government intervention, a hallmark of Republican economic philosophy at the time. He resisted direct relief efforts, fearing they would undermine individual initiative and create dependency on the federal government. Instead, he emphasized voluntary cooperation and local solutions, such as encouraging businesses to maintain wages and supporting private charities. While these principles aligned with his party’s ideology, they proved inadequate in the face of a crisis of such magnitude. The result was a deepening of public suffering and a loss of confidence in Hoover’s leadership.

To understand the impact of Hoover’s policies, compare them to the New Deal initiatives implemented by his successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s administration took a more interventionist approach, launching massive public works projects, establishing social safety nets, and regulating the financial sector. These measures, though not without flaws, helped stabilize the economy and restore public trust. In contrast, Hoover’s reluctance to embrace bold federal action left his administration struggling to contain the crisis, cementing the Great Depression as a defining failure of Republican economic stewardship during his tenure.

For those studying economic history or seeking lessons for modern policy, the Hoover administration’s handling of the Great Depression offers a cautionary tale. It underscores the importance of timely and decisive action in the face of economic collapse. While ideological principles are valuable, they must be balanced with pragmatic responses to crises. The mass unemployment, bank failures, and widespread suffering under Hoover’s watch serve as a stark reminder of the consequences when policy falls short of the moment’s demands.

Political Parties' Influence: Shaping Society's Values, Policies, and Future

You may want to see also

1970s stagflation crisis: Carter's Democratic era marked by high inflation, slow growth

The 1970s stagflation crisis remains one of the most challenging economic periods in American history, and Jimmy Carter’s Democratic presidency (1977–1981) was squarely at its epicenter. Stagflation—a toxic mix of high inflation, slow economic growth, and rising unemployment—defied traditional economic remedies. By 1980, inflation had soared to 13.5%, unemployment reached 7.8%, and GDP growth stagnated at 2.5%. Carter’s era became a case study in the limitations of Keynesian policies and the complexities of managing an economy amid global oil shocks and structural shifts.

To understand the crisis, consider the perfect storm of external and internal factors. The 1973 and 1979 oil embargoes, triggered by geopolitical tensions, sent energy prices skyrocketing, disrupting industries reliant on cheap oil. Domestically, wage-price controls under Nixon and Ford had created inefficiencies, while the Federal Reserve’s accommodative monetary policy fueled inflation. Carter’s administration inherited this mess but struggled to implement effective solutions. His 1978 energy plan, for instance, called for conservation and alternative fuels but lacked immediate impact. Similarly, his appointment of Paul Volcker as Fed Chair in 1979, while pivotal in the long term, initially exacerbated economic pain through tight monetary policy.

A comparative analysis highlights the unique challenges of the Carter era. Unlike the Great Depression, which was addressed with massive fiscal stimulus, or the 2008 financial crisis, tackled with bailouts and quantitative easing, stagflation defied conventional tools. Keynesian spending risked worsening inflation, while austerity threatened growth. Carter’s attempts to balance these extremes—such as his 1978 stimulus package and subsequent budget cuts—often fell short. The result was a public perception of indecisiveness, culminating in his infamous "malaise" speech, which, though misnamed, underscored a sense of national frustration.

For policymakers today, the Carter era offers critical lessons. First, structural issues like energy dependence require long-term solutions, not quick fixes. Second, central bank independence is crucial; Volcker’s aggressive rate hikes, though painful, ultimately tamed inflation. Finally, clear communication is essential. Carter’s inability to articulate a coherent economic vision eroded public trust. Modern leaders facing similar crises—such as supply chain disruptions or climate-driven inflation—must prioritize transparency and adaptability.

In practical terms, individuals and businesses can draw actionable insights from this period. Diversifying energy sources, as Carter advocated, remains relevant in an era of volatile oil markets. For investors, stagflation underscores the importance of inflation-resistant assets like TIPS or real estate. Policymakers, meanwhile, should heed the cautionary tale of over-reliance on monetary policy alone. The 1970s stagflation crisis was not merely a Democratic failure but a reminder of the economy’s complexity—and the high stakes of getting it wrong.

Revamping Democracy: Key Political Party Reforms Shaping Modern Governance

You may want to see also

2008 financial crisis: Bush's Republican term saw housing collapse, bank bailouts

The 2008 financial crisis stands as a stark example of economic turmoil during a Republican administration, specifically under President George W. Bush. This crisis, often referred to as the Great Recession, was characterized by a catastrophic housing market collapse and the subsequent bailout of major financial institutions. The roots of this disaster can be traced back to deregulation policies and a lack of oversight in the financial sector, which allowed risky lending practices to proliferate.

The Housing Bubble Bursts

In the years leading up to 2008, the U.S. housing market experienced an unprecedented boom, fueled by low-interest rates and lax lending standards. Subprime mortgages, often given to borrowers with poor credit histories, were bundled into complex financial instruments and sold to investors worldwide. This created a false sense of security, as the value of homes seemed to rise indefinitely. However, by 2006, the bubble began to deflate. Home prices plummeted, leaving millions of homeowners with mortgages exceeding the value of their properties. Foreclosures skyrocketed, triggering a domino effect that destabilized the entire financial system.

Bank Bailouts and Public Outcry

As major financial institutions like Lehman Brothers collapsed and others teetered on the brink, the Bush administration intervened with a controversial $700 billion bailout package, known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). While the bailout prevented a complete financial meltdown, it sparked widespread public outrage. Critics argued that taxpayer money was being used to rescue the very institutions whose reckless behavior caused the crisis. This intervention highlighted a fundamental tension between free-market principles and the necessity of government intervention during systemic failures.

Economic Fallout and Long-Term Consequences

The 2008 crisis led to the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, with unemployment peaking at 10% in 2009. Millions lost their homes, retirement savings, and jobs. The recovery was slow and uneven, with middle- and lower-income households bearing the brunt of the impact. The crisis also exposed deep-seated issues in the U.S. economy, including income inequality and the fragility of a financial system reliant on speculative practices.

Lessons and Takeaways

The 2008 financial crisis serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of deregulation and the importance of robust oversight in the financial sector. It underscores the need for policies that balance economic growth with protections for consumers and taxpayers. While the Bush administration’s response prevented a total collapse, it also revealed the limitations of ideological adherence to free-market principles in the face of systemic risk. For individuals, the crisis highlights the importance of financial literacy, diversification, and caution when engaging with complex financial products.

John McCain's Political Journey: Did He Switch Parties?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Post-WWII recession: Truman's Democratic policies led to severe economic downturn in 1949

The post-World War II recession of 1949 stands as a stark example of how rapid policy shifts can destabilize an economy. As the war ended, the U.S. transitioned from a wartime to a peacetime economy, a process fraught with challenges. President Harry Truman’s Democratic administration implemented policies aimed at demobilization and fiscal austerity, which inadvertently triggered a severe economic downturn. The recession saw unemployment spike to 7.9% and GDP contract by 1.1%, raising questions about the role of government intervention in economic transitions.

To understand the recession’s roots, consider the abrupt end to wartime spending. During WWII, government expenditures had soared to 40% of GDP, fueling industrial production and employment. Truman’s policies, however, prioritized budget balancing and price controls, leading to a sharp reduction in demand. For instance, the removal of price controls in 1946 caused inflation to surge to 14%, eroding consumer purchasing power. Simultaneously, veterans returning to the workforce faced a labor market ill-prepared for their reintegration, exacerbating unemployment.

A comparative analysis reveals the recession’s severity relative to other post-war periods. Unlike the smoother transitions in later decades, the 1949 downturn was marked by policy missteps. Truman’s reliance on fiscal contraction and failure to stimulate private investment contrasted with Eisenhower’s later focus on infrastructure and defense spending. This highlights the importance of phased, rather than abrupt, economic policy changes during transitions.

Practical takeaways from this period emphasize the need for gradual policy adjustments during economic shifts. Policymakers should balance fiscal responsibility with targeted stimulus measures, such as temporary tax cuts or job retraining programs. For individuals, the recession underscores the value of diversifying skills and savings to withstand economic volatility. By studying Truman’s policies, we gain insights into the delicate balance between austerity and growth, a lesson as relevant today as it was in 1949.

Unveiling the Unexpected: What Political Parties Don't Spend Big On

You may want to see also

Early 1800s Panic: Democratic-Republican Party faced economic chaos during the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 marked the first major financial crisis in the United States, and it unfolded squarely under the watch of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by President James Monroe. This crisis, often overshadowed by later economic downturns, offers a critical case study in the intersection of politics and economic mismanagement. Triggered by a combination of post-war inflation, speculative land investments, and the contraction of credit, the Panic exposed vulnerabilities in the young nation’s economy and the limitations of the Democratic-Republicans’ agrarian-focused policies. The party’s ideological commitment to limited federal intervention and state banking autonomy inadvertently exacerbated the crisis, leaving farmers, merchants, and laborers to bear the brunt of widespread bankruptcies, unemployment, and social unrest.

To understand the Panic of 1819, consider its origins in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The Democratic-Republicans, who championed states’ rights and agrarian interests, had encouraged the expansion of state-chartered banks, leading to a surge in credit and speculative land purchases. However, when the Second Bank of the United States began to tighten credit in 1818, the bubble burst. Land values plummeted, banks failed, and unemployment soared. The party’s resistance to federal intervention meant there was no coordinated response to stabilize the economy. Instead, states were left to fend for themselves, resulting in a patchwork of ineffective solutions. This hands-off approach deepened the crisis, which lasted until the mid-1820s, leaving a legacy of economic hardship and political disillusionment.

A comparative analysis reveals the Panic of 1819 as a cautionary tale about the risks of ideological rigidity in economic policy. While the Democratic-Republicans’ emphasis on states’ rights aligned with their Jeffersonian principles, it proved ill-suited to address a national economic crisis. In contrast, later administrations, such as those during the Great Depression, embraced federal intervention to mitigate economic collapse. The Panic of 1819 underscores the importance of adaptability in governance, particularly when ideological purity conflicts with practical solutions. For modern policymakers, this historical episode serves as a reminder that economic crises often demand bold, centralized action, even if it challenges prevailing political philosophies.

Practically speaking, the Panic of 1819 offers lessons for managing economic instability today. First, monitor speculative bubbles, especially in real estate, as unchecked speculation can lead to devastating crashes. Second, ensure regulatory frameworks are in place to prevent excessive risk-taking by financial institutions. Third, recognize the limitations of decentralized responses to national crises; coordination at the federal level is often essential. Finally, prioritize social safety nets during downturns, as the human cost of economic collapse—unemployment, poverty, and displacement—can outlast the financial recovery. By studying the Democratic-Republicans’ missteps, we can better prepare for and mitigate future economic shocks.

The Jacobin Club: Danton, Marat, Robespierre's Radical Revolution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Economic performance is influenced by multiple factors, including global events, policies, and timing, making it difficult to attribute "worst economies" solely to a political party. However, the Great Depression (1929–1939) occurred under Republican President Herbert Hoover, though its causes were complex and not entirely partisan.

The highest unemployment rate in U.S. history (24.9%) occurred during the Great Depression under Republican President Herbert Hoover. However, economic crises often result from a combination of factors, not solely partisan policies.

Both parties have contributed to national debt increases, often due to wars, recessions, or stimulus spending. For example, Republican tax cuts under George W. Bush and Donald Trump, as well as Democratic spending under Barack Obama and Joe Biden, have all added to the debt.

Major recessions have occurred under both parties. The Great Depression (Republican) and the 2008 financial crisis (Republican under George W. Bush) are notable examples. Economic downturns are often driven by broader systemic issues rather than partisan affiliation alone.