In the 1850s, the American political landscape was significantly shaped by the rise of nativism, a movement characterized by hostility toward immigrants, particularly Catholics and Irish newcomers. The American Party, commonly known as the Know-Nothing Party, emerged as the primary political force championing nativist ideals during this period. Formed in the early 1850s, the party capitalized on widespread fears of immigrant influence on American culture, politics, and the economy. Its platform centered on restricting immigration, limiting the political power of naturalized citizens, and promoting Protestant values. While the Know-Nothing Party initially gained traction, its focus on nativism ultimately limited its broader appeal, and it declined by the end of the decade as the nation's attention shifted to the more pressing issue of slavery.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | American Party (also known as the Know-Nothing Party) |

| Focus | Nativism, anti-immigration, anti-Catholicism |

| Active Period | 1840s–1860s (peak in the 1850s) |

| Key Issues | Restricting immigration, extending naturalization periods, anti-Catholic sentiment |

| Base of Support | Native-born, Protestant Americans, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest |

| Political Stance | Opposed to Irish and German Catholic immigrants |

| Notable Leaders | Samuel F.B. Morse, Lewis C. Levin, Nathaniel P. Banks |

| Election Success | Won several state and local elections in the mid-1850s |

| Decline | Collapsed after the 1856 presidential election due to internal divisions and the rise of the Republican Party |

| Legacy | Highlighted tensions over immigration and religious differences in 19th-century America |

Explore related products

$11.14 $5.42

What You'll Learn

- Know-Nothing Party Origins: Formed as Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, emphasizing secrecy and anti-immigrant sentiment

- Anti-Catholic Stance: Opposed Catholic immigration, fearing political influence and threats to Protestant values

- American Nativist Goals: Prioritized native-born citizens' rights over immigrants in jobs and politics

- Key Leaders: Figures like Samuel Morse and Lewis Lemon drove the party's nativist agenda

- Election Decline: Failed presidential bid marked the party's rapid downfall due to internal divisions

Know-Nothing Party Origins: Formed as Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, emphasizing secrecy and anti-immigrant sentiment

The Know-Nothing Party, a mid-19th-century political force, emerged from the shadows of secret societies, its roots deeply intertwined with nativist fears and anti-immigrant fervor. Born as the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner in the early 1850s, this organization was not merely a political party but a clandestine movement, shrouded in secrecy and ritual. Members were bound by an oath of silence, earning them the moniker "Know-Nothings" due to their evasive responses when questioned about their activities. This secrecy was not just a tactic but a core tenet, fostering an air of exclusivity and mystery that attracted disaffected citizens seeking a radical solution to the era's social and economic upheavals.

The Order's transformation into a political party was a strategic evolution, capitalizing on the growing anxiety among native-born Americans about the influx of Irish and German immigrants. These newcomers, often Catholic, were seen as threats to the nation's Protestant identity and economic stability. The Know-Nothings' platform was clear: restrict immigration, limit the political power of immigrants, and preserve what they perceived as the nation's original cultural and religious character. Their anti-immigrant sentiment was not just a policy but a rallying cry, tapping into the fears and frustrations of a population grappling with rapid demographic changes.

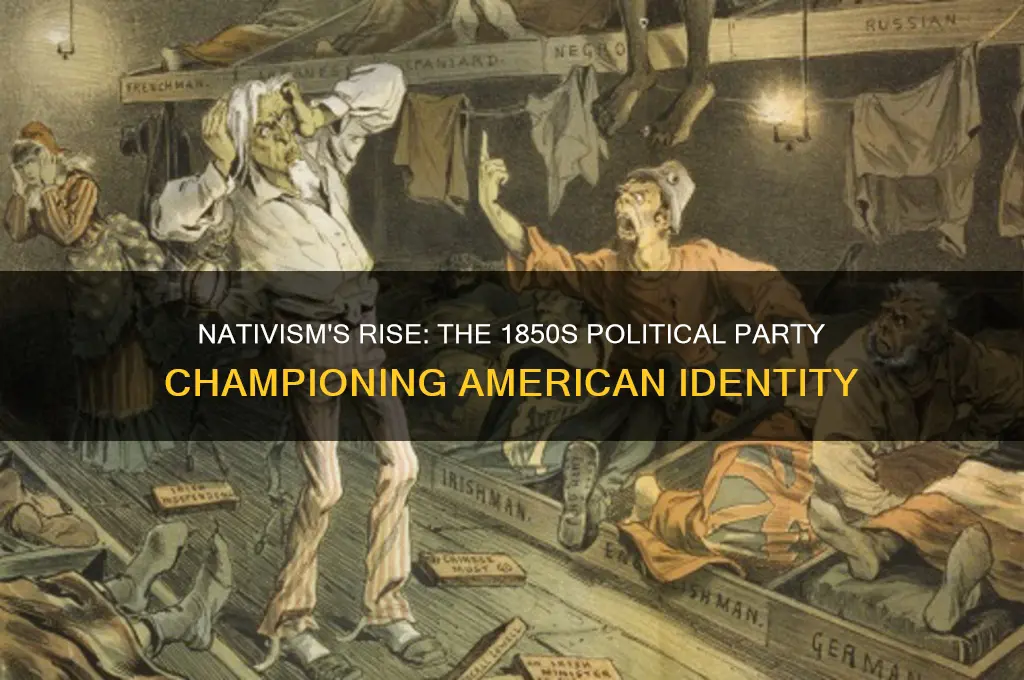

To understand the Know-Nothings' appeal, consider the social climate of the 1850s. Immigration was at an all-time high, with over 2 million arrivals between 1840 and 1860, many fleeing famine and revolution in Europe. Cities like New York and Boston were bursting at the seams, and competition for jobs and resources was fierce. The Know-Nothings offered a simple, if divisive, solution: blame the immigrants. Their message resonated with those who felt left behind by the nation's rapid industrialization and urbanization, providing a scapegoat for economic woes and social unrest.

The party's organizational structure was as unique as its origins. Local chapters, known as "lodges," operated with military-like discipline, complete with passwords, handshakes, and hierarchical ranks. This structure not only ensured secrecy but also created a sense of belonging and purpose for its members. The Know-Nothings' ability to mobilize and organize was a key factor in their rapid rise, winning local and state elections across the North and even capturing the governor's office in Massachusetts in 1854.

However, the very secrecy that fueled the Know-Nothings' initial success also sowed the seeds of their demise. As the party gained prominence, its clandestine nature became a liability. The public's fascination with their mysterious rituals eventually turned to suspicion and ridicule. Moreover, the party's single-minded focus on nativism failed to address the complex issues of the day, such as slavery, which increasingly dominated the national discourse. By the late 1850s, the Know-Nothings had fractured, their members dispersing to other parties or fading into political obscurity.

In retrospect, the Know-Nothing Party serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of exclusionary politics and the allure of simplistic solutions to complex problems. Their emphasis on secrecy and anti-immigrant sentiment, while effective in the short term, ultimately undermined their legitimacy and sustainability. Yet, their story also highlights the enduring appeal of nativist rhetoric, a reminder that the fears and anxieties they exploited are not confined to the past but continue to shape political movements today.

Why Political Talk Shows Dominate Media and Shape Public Opinion

You may want to see also

Anti-Catholic Stance: Opposed Catholic immigration, fearing political influence and threats to Protestant values

The 1850s in America were marked by a surge in nativist sentiment, fueled by the rapid influx of Irish Catholic immigrants fleeing the Great Famine. This demographic shift ignited fears among certain segments of the population, particularly Protestants, who viewed Catholicism as a threat to their religious, cultural, and political dominance. The Know-Nothing Party, formally known as the American Party, emerged as the primary political vehicle for these anxieties, championing an anti-Catholic stance that resonated deeply with its base.

At the heart of the Know-Nothing Party’s platform was the belief that Catholic immigrants, particularly the Irish, posed an existential threat to American Protestantism. Party leaders and supporters argued that Catholics owed their primary allegiance to the Pope, not the U.S. Constitution, and thus could not be trusted as loyal citizens. This suspicion was compounded by the Catholic Church’s growing institutional presence, including the establishment of parochial schools and charities, which nativists saw as a direct challenge to public, Protestant-dominated institutions. The party’s rhetoric often portrayed Catholic immigration as a deliberate plot to undermine American values and install papal authority in the nation’s political and social fabric.

To combat this perceived threat, the Know-Nothing Party advocated for restrictive immigration policies and longer naturalization periods for newcomers, particularly Catholics. They also pushed for "Protestant" reforms, such as mandatory Bible readings in public schools using the King James Version, which was seen as a Protestant text. These measures were designed not only to limit Catholic influence but also to reinforce the dominance of Protestant culture in American society. The party’s anti-Catholic stance was so central to its identity that it often overshadowed other issues, making it a single-issue movement in the eyes of critics.

The Know-Nothing Party’s focus on anti-Catholicism was not merely theoretical; it had tangible consequences for immigrant communities. In cities like Boston and New York, where Irish Catholics were concentrated, Know-Nothing supporters engaged in acts of violence and intimidation, including the burning of Catholic churches and schools. These actions were justified as necessary to protect American Protestantism from what was perceived as an invasive, foreign ideology. The party’s rise also coincided with the passage of local and state laws aimed at curtailing Catholic influence, such as the Blaine Amendments, which prohibited public funding for sectarian schools—a measure clearly targeted at Catholic institutions.

Despite its initial popularity, the Know-Nothing Party’s anti-Catholic stance ultimately proved unsustainable. The party’s narrow focus alienated moderate voters, and its inability to address broader economic and social issues led to its decline by the late 1850s. However, the legacy of its anti-Catholic nativism persisted, shaping American immigration policy and religious discourse for decades. The Know-Nothing movement serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of politicizing religious differences and the long-term consequences of exclusionary policies. For those studying nativism or seeking to understand contemporary debates about immigration and religious identity, the Know-Nothing Party’s anti-Catholic stance offers a stark reminder of how fear and misinformation can drive political movements with lasting impacts.

Fernando Dutra's Political Affiliation: Unveiling His Party Membership

You may want to see also

American Nativist Goals: Prioritized native-born citizens' rights over immigrants in jobs and politics

In the 1850s, the American Party, commonly known as the Know-Nothing Party, emerged as the primary political force championing nativist goals. Their central objective was clear: to prioritize the rights and interests of native-born citizens over those of immigrants, particularly in the realms of employment and political participation. This movement was fueled by growing anxieties about the influx of Irish and German immigrants, who were often Catholic, and the perceived threat they posed to Protestant American values and economic stability.

To achieve their goals, the Know-Nothings advocated for restrictive immigration policies and longer naturalization processes, aiming to limit the political and economic influence of newcomers. For instance, they pushed for a 21-year residency requirement for citizenship, a stark contrast to the then-standard 5-year period. This measure was designed to delay immigrants’ eligibility to vote and hold office, effectively sidelining them from the political process. In the labor market, nativists pressured employers to hire native-born workers first, often through boycotts and public shaming campaigns. These tactics were particularly prevalent in urban areas like Boston and New York, where immigrant populations were concentrated and competition for jobs was fierce.

The Know-Nothings’ rhetoric often framed immigrants as unassimilable and economically burdensome, a narrative that resonated with many native-born Americans facing economic hardship. They argued that immigrants, especially the Irish, were willing to work for lower wages, undercutting native workers and depressing overall labor conditions. While this claim was often exaggerated, it effectively mobilized support for nativist policies. For example, in 1855, the party won control of the Massachusetts legislature and promptly passed laws restricting immigrant access to public welfare and limiting their ability to serve on juries or in public office. These measures were not just symbolic; they had tangible impacts on the lives of immigrants and the communities they inhabited.

However, the Know-Nothings’ focus on nativism was not without its contradictions. While they claimed to protect native-born citizens, their policies often exacerbated social divisions and ignored the structural economic issues of the time. For instance, their emphasis on restricting immigrant labor did little to address the root causes of unemployment, such as industrialization and economic inequality. Moreover, their anti-Catholic stance alienated a significant portion of the population and ultimately contributed to the party’s decline by the late 1850s. Despite their short-lived prominence, the Know-Nothings’ legacy underscores the enduring tension between inclusion and exclusion in American politics.

In practical terms, understanding the Know-Nothings’ goals offers insights into the recurring themes of nativism in U.S. history. Their strategies—restrictive policies, economic protectionism, and cultural fear-mongering—have been echoed in various movements throughout the centuries. For those studying or addressing contemporary immigration debates, examining this period provides a historical lens through which to analyze current policies and their potential consequences. By recognizing the complexities and limitations of nativist goals, we can better navigate the challenges of fostering a just and inclusive society.

How Canada's Political Parties Earn Funding Through Votes: Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21.49 $37

$21.69 $29.99

$33.13 $52.99

Key Leaders: Figures like Samuel Morse and Lewis Lemon drove the party's nativist agenda

The Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s was fueled by the fiery rhetoric and organizational prowess of key leaders who championed nativist ideals. Among these figures, Samuel Morse and Lewis Lemon stand out for their distinct contributions to the party’s agenda. Morse, best known as the inventor of the telegraph, was also a vocal anti-Catholic and nativist writer. His pamphlets and essays warned of a supposed Catholic conspiracy to undermine American values, framing immigration as a threat to the nation’s Protestant foundation. Lemon, on the other hand, was a lesser-known but equally influential organizer who helped build the party’s grassroots structure, ensuring its message reached rural and urban communities alike. Together, they exemplified how intellectual and practical leadership could converge to drive a political movement.

Analyzing their roles reveals a strategic division of labor within the Know-Nothing Party. Morse’s intellectual contributions provided the ideological backbone, legitimizing nativist fears through his reputation as a respected inventor and thinker. His writings, such as *Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States*, were widely circulated and amplified the party’s anti-immigrant narrative. Lemon, meanwhile, focused on the nuts and bolts of organizing, mobilizing local chapters and ensuring the party’s message resonated with everyday Americans. This combination of high-minded ideology and ground-level activism was critical to the Know-Nothings’ rise, demonstrating how leaders with complementary skills can maximize a movement’s impact.

A persuasive argument can be made that Morse and Lemon’s influence extended beyond their lifetimes, shaping the trajectory of American nativism. Morse’s warnings about the dangers of immigration laid the groundwork for future restrictionist policies, while Lemon’s organizational tactics became a blueprint for later populist movements. Their legacy underscores the enduring power of charismatic leadership in shaping political agendas. For modern activists or organizers, the lesson is clear: pairing intellectual rigor with practical action can create a potent force for change, though the morality of that change depends on the values it promotes.

Comparatively, Morse and Lemon’s roles highlight the tension between elitist and populist approaches within nativist movements. Morse’s intellectual elitism appealed to educated classes, while Lemon’s grassroots efforts tapped into the frustrations of the working class. This duality allowed the Know-Nothings to bridge societal divides, a strategy still employed by contemporary populist movements. However, it also raises cautionary questions about the manipulation of public sentiment. Leaders like Morse and Lemon wielded significant influence, but their nativist agenda ultimately contributed to xenophobia and division. Aspiring leaders should note: the tools of persuasion and organization are powerful, but their ethical use is paramount.

Descriptively, the impact of Morse and Lemon’s leadership can be seen in the Know-Nothing Party’s rapid ascent and equally swift decline. By 1856, the party had elected hundreds of officials across the country, a testament to their effectiveness. Yet, their failure to sustain momentum beyond the mid-1850s illustrates the limitations of a movement built on fear and exclusion. Morse’s intellectual arguments and Lemon’s organizational skills were formidable, but they could not overcome the party’s lack of a broader, inclusive vision. This historical example serves as a practical tip for modern movements: while strong leadership can drive rapid growth, long-term success requires a unifying message that transcends division.

Switching Political Parties in South Carolina: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

1856 Election Decline: Failed presidential bid marked the party's rapid downfall due to internal divisions

The 1856 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, marking the decline of the American Party, also known as the Know-Nothing Party, which had risen to prominence on a platform of nativism and anti-immigration sentiment. This election exposed the party's internal fractures, ultimately leading to its rapid downfall. The Know-Nothings, who had gained significant traction in the early 1850s, fielded former President Millard Fillmore as their candidate, but his bid for the presidency failed to unite the party's diverse factions.

The Rise and Fall of a Nativist Movement

The American Party's appeal in the 1850s was rooted in its nativist ideology, which targeted immigrants, particularly Catholics, as threats to American values and jobs. By 1855, the party had secured victories in local and state elections, controlling legislatures in several Northern states. However, this success masked deep internal divisions. The party’s base was a fragile coalition of anti-Catholic Protestants, labor reformers, and former Whigs, united more by what they opposed than by a shared vision. When the 1856 election approached, these divisions became insurmountable. Southern Know-Nothings prioritized states' rights and slavery, while Northern members focused on immigration and temperance, creating irreconcilable differences.

Fillmore’s Failed Candidacy: A Symptom of Disunity

Millard Fillmore’s nomination as the American Party’s presidential candidate exemplified the party’s internal strife. Fillmore, a former Whig, was chosen as a compromise candidate, but his moderate stance on slavery alienated both pro-slavery Southerners and anti-slavery Northerners within the party. His campaign failed to galvanize the nativist base, as the party’s core issues were overshadowed by the growing national debate over slavery. The Know-Nothings’ inability to present a unified front on this critical issue further eroded their support. Fillmore’s poor showing in the election, winning only Maryland, signaled the party’s inability to sustain its earlier momentum.

Internal Divisions as the Catalyst for Decline

The 1856 election exposed the American Party’s fatal flaw: its lack of a cohesive platform beyond nativism. As the slavery issue intensified, the party’s members drifted toward the emerging Republican Party in the North and the Democratic Party in the South. The Know-Nothings’ failure to address this ideological split left them politically irrelevant. By 1857, the party’s influence had waned significantly, and it disbanded shortly thereafter. The lesson is clear: political movements built on narrow, divisive issues like nativism are inherently fragile and susceptible to collapse when broader national crises arise.

Practical Takeaways for Political Movements

For modern political movements, the Know-Nothings’ decline offers a cautionary tale. Parties must cultivate a broad, inclusive platform that addresses diverse constituent concerns rather than relying on a single divisive issue. Internal unity is paramount, especially during elections, as factions can quickly undermine a party’s viability. Additionally, adaptability to shifting national priorities is crucial; failure to evolve leaves movements vulnerable to dissolution. The American Party’s downfall serves as a reminder that short-term gains built on exclusionary policies are no substitute for long-term, principled coalition-building.

Is Columbia University Affiliated with a Political Party? Exploring the Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The American Party, also known as the Know-Nothing Party, was the primary political party that focused on nativism in the 1850s.

The nativist American Party aimed to restrict immigration, particularly from Ireland and Germany, and to limit the political influence of Catholics, whom they viewed as a threat to American values and institutions.

The American Party gained popularity by exploiting anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments, especially in the Northeast and Midwest, and by using secrecy and oaths to build a loyal membership base.

The American Party declined due to internal divisions, the rise of the Republican Party as a more viable anti-slavery alternative, and the party's inability to address the growing issue of slavery, which overshadowed nativist concerns.