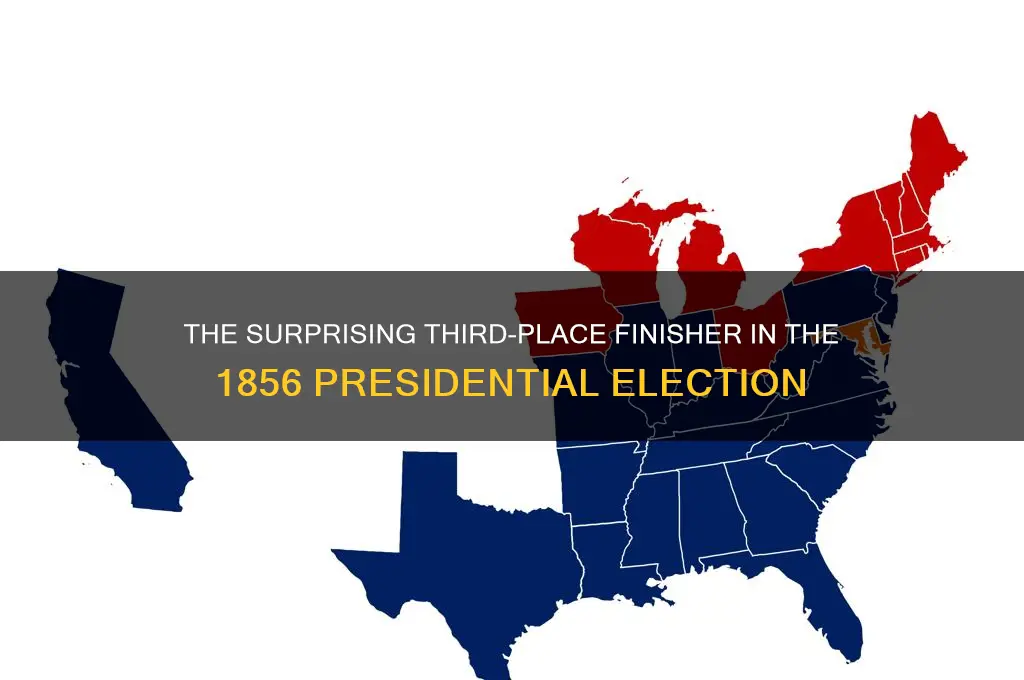

The 1856 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by the rise of the Republican Party and the deepening divisions over slavery. While the Democratic Party’s candidate, James Buchanan, secured victory, and the newly formed Republican Party’s John C. Frémont finished second, the third-place position went to the Know Nothing Party, also known as the American Party. Their candidate, former President Millard Fillmore, captured 21.5% of the popular vote and carried the state of Maryland, reflecting the party’s appeal to nativist sentiments and its opposition to immigration and Catholic influence. This election underscored the shifting political landscape as the nation moved closer to the Civil War.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Know Nothing Party (officially known as the American Party) |

| Year Founded | 1844 (as the Native American Party); reorganized as the American Party in 1854 |

| Ideology | Nativism, Anti-Catholicism, Anti-Immigration, Populism |

| Key Figures | President Millard Fillmore (1856 candidate), Samuel Morse, Lewis Charles Levin |

| 1856 Presidential Candidate | Millard Fillmore |

| 1856 Electoral Votes | 8 |

| 1856 Popular Vote | 873,053 (21.5% of total votes) |

| Platform in 1856 | Opposition to immigration, particularly Catholic immigration; support for Protestantism and nativist policies |

| Decline | Disbanded after the 1856 election due to internal divisions and the rise of the Republican Party |

| Historical Significance | Highlighted the tensions over immigration and religion in mid-19th century America |

| Legacy | Often cited as an example of nativist movements in U.S. history |

Explore related products

$14.75

$22.95

What You'll Learn

- Know-Nothing Party's Rise: Anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic platform gained traction in the 1850s

- Candidate Millard Fillmore: Former President ran as the Know-Nothing Party's nominee

- Election Results: Fillmore secured 21.5% of the popular vote, finishing third

- Impact on Politics: Highlighted growing sectional tensions and nativist sentiment in America

- Historical Context: Occurred during the prelude to the Civil War, shaping political realignment

Know-Nothing Party's Rise: Anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic platform gained traction in the 1850s

The 1856 presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, with the Know-Nothing Party emerging as the third-place finisher. This party, formally known as the American Party, capitalized on widespread anxieties about immigration and the growing influence of the Catholic Church. Their platform, rooted in nativism and anti-Catholicism, resonated with a significant portion of the electorate, particularly in the North. By examining the rise of the Know-Nothings, we can understand how fear and prejudice shaped political movements in the mid-19th century.

To grasp the Know-Nothings' appeal, consider the demographic shifts of the 1850s. The United States experienced a surge in Irish and German immigration, many of whom were Catholic. These newcomers often competed with native-born Americans for jobs and housing, fueling resentment. The Know-Nothings exploited these tensions, advocating for stricter naturalization laws and a 21-year residency requirement for citizenship. They also pushed for public schools free from Catholic influence, tapping into fears that the Church sought to control American institutions. For instance, in Massachusetts, the party gained control of the state legislature and passed laws limiting the political power of immigrants.

The Know-Nothings' secrecy added to their mystique and appeal. Members were sworn to respond "I know nothing" when asked about the party's activities, earning them their nickname. This clandestine nature allowed the party to spread its message without immediate backlash, particularly in areas where anti-immigrant sentiment was already high. However, their secrecy also limited their long-term viability, as it hindered transparency and trust among voters. Despite this, their success in local and state elections demonstrated the potency of their platform.

A key takeaway from the Know-Nothings' rise is the danger of politicizing fear. By framing immigrants and Catholics as threats to American values, the party mobilized a substantial following but also deepened societal divisions. Their influence waned after 1856, as the slavery debate overshadowed nativist concerns. Yet, their legacy endures as a cautionary tale about the consequences of exploiting prejudice for political gain. Understanding this chapter in history offers insights into how similar movements have emerged in other times and places, reminding us of the importance of addressing root causes of fear rather than amplifying them.

Joining Local Politics: A Step-by-Step Guide to Signing Up for a Political Party

You may want to see also

Candidate Millard Fillmore: Former President ran as the Know-Nothing Party's nominee

The 1856 presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as the nation grappled with the escalating tensions over slavery. Amidst this turmoil, the Know-Nothing Party emerged as a significant force, securing the third-place finish with former President Millard Fillmore as its nominee. Fillmore’s candidacy was a testament to the party’s unique appeal, blending nativist sentiments with a platform that sought to sidestep the divisive issue of slavery. This section delves into Fillmore’s role, the Know-Nothing Party’s strategy, and the broader implications of their third-place finish.

Analytical Perspective:

Millard Fillmore’s decision to run as the Know-Nothing Party’s nominee was both strategic and symbolic. As a former Whig President, Fillmore brought legitimacy to a party often dismissed as fringe. The Know-Nothings, formally known as the American Party, capitalized on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic fears, positioning themselves as defenders of native-born Protestant Americans. Fillmore’s candidacy allowed the party to pivot from its radical roots toward a more mainstream appeal, though it ultimately failed to secure the presidency. His 21.5% share of the popular vote and 8 electoral votes underscored the party’s temporary but notable influence, reflecting the electorate’s desire for an alternative to the dominant Democrats and Republicans.

Instructive Approach:

To understand Fillmore’s role, consider the Know-Nothing Party’s platform. They advocated for a 21-year naturalization period for immigrants, restrictions on foreign-born officials, and the preservation of Protestant values. Fillmore’s campaign focused on these issues while carefully avoiding a clear stance on slavery, a tactic known as "Know-Nothingism" itself. This strategy aimed to unite Northern and Southern voters under a common cause, but it also highlighted the party’s inability to address the era’s most pressing moral question. For historians or political analysts, studying Fillmore’s campaign offers insights into how parties navigate divisive issues by emphasizing identity politics.

Comparative Analysis:

Compared to other third-party candidates in U.S. history, Fillmore’s performance stands out for its context rather than its outcome. Unlike Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in 1912 or Ross Perot’s Reform Party in 1992, the Know-Nothings lacked a coherent long-term vision. Fillmore’s candidacy was a fleeting attempt to capitalize on temporary anxieties rather than a sustained movement. However, like these later third parties, the Know-Nothings exposed the fragility of the two-party system during times of crisis. Their decline after 1856 mirrors the fate of many third parties, which often struggle to maintain relevance beyond a single election cycle.

Descriptive Narrative:

The 1856 campaign trail was a spectacle of contrasting styles. While Democrat James Buchanan and Republican John C. Frémont clashed over slavery, Fillmore’s rallies were marked by nativist fervor. Banners reading “Americans Shall Rule America” and speeches decrying foreign influence dominated his events. Yet, Fillmore’s own demeanor—calm and statesmanlike—contrasted with the party’s fiery rhetoric. This duality reflected the Know-Nothings’ internal tensions: a former President lending respectability to a party rooted in xenophobia. Despite this, Fillmore’s ability to secure over 870,000 votes demonstrated the depth of nativist sentiment in mid-19th-century America.

Persuasive Argument:

Millard Fillmore’s candidacy as the Know-Nothing nominee serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of avoiding critical issues. By sidestepping slavery, the party failed to offer a meaningful solution to the nation’s deepest divide, ensuring its eventual irrelevance. Today, as political parties navigate polarizing topics, Fillmore’s example reminds us that short-term expediency often comes at the cost of long-term viability. For modern candidates, the lesson is clear: addressing core issues head-on, rather than exploiting peripheral fears, is essential for enduring political impact.

Exploring Germany's Political Landscape: Parties, Ideologies, and Influence

You may want to see also

Election Results: Fillmore secured 21.5% of the popular vote, finishing third

The 1856 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by deep divisions over slavery and the emergence of new parties. Amidst this turmoil, former President Millard Fillmore, running as the candidate for the Know-Nothing Party (formally known as the American Party), secured 21.5% of the popular vote, finishing third behind James Buchanan of the Democratic Party and John C. Frémont of the newly formed Republican Party. This result underscores the Know-Nothing Party’s temporary but significant appeal to voters who sought alternatives to the dominant political forces of the time.

Analytically, Fillmore’s performance reflects the Know-Nothing Party’s unique platform, which focused on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments rather than the slavery issue that dominated national discourse. While this stance resonated with a substantial portion of the electorate, it failed to translate into electoral victory. The party’s inability to secure a majority in any state highlights the limitations of its narrow focus, especially in an era when sectional tensions over slavery were reshaping political alliances. Fillmore’s 21.5% share of the popular vote, however, demonstrates that the Know-Nothing Party tapped into real anxieties among voters, even if its influence was short-lived.

From a comparative perspective, Fillmore’s third-place finish contrasts sharply with his earlier political career, including his tenure as president after the death of Zachary Taylor. In 1856, he was no longer a figure of national unity but a symbol of a fringe movement. Meanwhile, the Republican Party’s rise with Frémont as its candidate signaled a realignment of American politics around the slavery issue. The Know-Nothing Party’s inability to compete with this new dynamic underscores the shifting priorities of the electorate and the growing polarization of the nation.

Practically, Fillmore’s result offers a cautionary tale for third-party candidates today. While securing 21.5% of the vote is no small feat, it also reveals the challenges of building a coalition around a single, divisive issue. Modern third-party candidates can learn from this example by broadening their appeal and addressing a wider range of voter concerns. For instance, focusing on economic or social issues in addition to immigration or cultural anxieties might create a more sustainable base of support.

Descriptively, the 1856 election map paints a vivid picture of Fillmore’s limited success. He performed best in states like Maryland and Louisiana, where anti-immigrant sentiment was particularly strong, but failed to make inroads in the North or the Deep South. This geographic distribution reflects the Know-Nothing Party’s regional appeal and its inability to transcend local concerns. Fillmore’s third-place finish, therefore, is not just a statistical footnote but a snapshot of a nation in flux, grappling with issues that would soon lead to its greatest crisis.

Gwen Stefani's Political Party: Unraveling Her Political Affiliations and Views

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21.48 $32.95

Impact on Politics: Highlighted growing sectional tensions and nativist sentiment in America

The 1856 presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, with the emergence of the Republican Party as a major force. However, it was the third-place finish of the Know-Nothing Party, officially known as the American Party, that underscored the deepening fault lines in the nation. This party's surprising success was not merely a footnote but a stark reflection of the growing sectional tensions and nativist sentiment that would soon plunge the country into crisis.

Analytically, the Know-Nothing Party's platform was a direct response to the anxieties of Northern Protestants who feared the influence of Catholic immigrants, particularly the Irish. Their slogan, "Americans must rule America," encapsulated a xenophobic and exclusionary ideology. By securing 21.5% of the popular vote and carrying one state, Maryland, the party demonstrated the potency of nativism as a political force. This was no fringe movement but a significant bloc that capitalized on economic insecurities and cultural fears, revealing how immigration and religious differences were becoming political weapons.

Instructively, the Know-Nothings' rise offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of exploiting division. Their anti-immigrant rhetoric and calls for stricter naturalization laws resonated in an era of rapid demographic change. For modern policymakers, this serves as a reminder that addressing economic and cultural anxieties without stoking prejudice is essential. Practical steps include fostering inclusive policies, promoting civic education, and combating misinformation that fuels nativist sentiments. Ignoring these lessons risks repeating history, where fear-driven politics fracture societies.

Persuasively, the Know-Nothings' success also highlights the fragility of political coalitions. Their inability to sustain momentum beyond 1856 was partly due to internal contradictions and the rise of the Republican Party, which absorbed many of their supporters. Yet, their brief ascendancy underscores how sectional tensions—North vs. South, native-born vs. immigrant—were reshaping American politics. This period reminds us that political parties must navigate these divisions carefully, balancing unity with diversity, or risk exacerbating the very conflicts they claim to address.

Comparatively, the Know-Nothings' focus on nativism contrasts sharply with the Republican Party's emphasis on slavery as the defining issue of the era. While the Republicans framed their agenda around moral and economic arguments against slavery, the Know-Nothings targeted immigrants as scapegoats for societal ills. This divergence reveals how different groups prioritized distinct threats, yet both parties capitalized on fear. The Know-Nothings' third-place finish thus serves as a historical marker of how competing anxieties can fragment a nation, a lesson as relevant today as it was in 1856.

Penn & Teller's Political Party: Unveiling Their Surprising Affiliation

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Occurred during the prelude to the Civil War, shaping political realignment

The 1856 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, occurring during the tumultuous prelude to the Civil War. This election was not merely a contest between candidates but a reflection of the deep ideological divisions tearing the nation apart. The emergence of the Republican Party, which finished second, marked a significant shift in the political landscape. However, the party that finished third—the Know-Nothing Party—offers a unique lens through which to understand the era’s complexities. Their rise and fall illustrate the volatile nature of American politics in the mid-19th century, as issues of immigration, slavery, and national identity reshaped party alignments.

To understand the Know-Nothing Party’s role, consider the political climate of the 1850s. The Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 had fractured the Whig Party, leaving a void in the political system. The Know-Nothings, formally known as the American Party, capitalized on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment, particularly in the North. Their platform appealed to those who feared the cultural and economic impact of immigration, but their inability to address the slavery issue left them vulnerable. While they won significant victories in the 1854 midterms, their failure to secure a strong position in the 1856 election signaled the limits of their appeal in a nation increasingly polarized over slavery.

Analytically, the Know-Nothing Party’s third-place finish highlights the fragility of single-issue movements in times of national crisis. Their focus on nativism failed to resonate in a country where the slavery debate dominated discourse. The Republican Party, by contrast, successfully coalesced anti-slavery sentiment, positioning itself as the dominant force in the North. The Know-Nothings’ decline underscores the importance of adaptability in politics, particularly during periods of realignment. Their inability to evolve beyond nativism rendered them irrelevant as the nation moved toward secession and war.

Instructively, the 1856 election serves as a cautionary tale for modern political movements. Parties or candidates that fail to address the most pressing issues of their time risk obsolescence. For instance, while the Know-Nothings tapped into genuine anxieties about immigration, their refusal to engage with the slavery question doomed their long-term prospects. Today, political strategists might note the importance of balancing core principles with responsiveness to broader societal concerns. The Know-Nothings’ trajectory reminds us that political survival often depends on the ability to pivot and broaden one’s appeal.

Finally, the Know-Nothing Party’s role in the 1856 election offers a comparative perspective on third-party movements. Unlike the Republicans, who successfully transitioned from a fringe group to a major party, the Know-Nothings faded into obscurity. This contrast highlights the difference between movements that address fundamental national divides and those that focus on narrower, often transient, concerns. As historians and political observers, we can draw parallels to contemporary third parties, urging them to learn from the Know-Nothings’ failure to adapt and evolve in the face of a changing political landscape.

Understanding the Roles and Ideologies of All Political Parties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Know-Nothing Party, officially known as the American Party, finished third in the 1856 presidential election.

Millard Fillmore, the former U.S. President, was the presidential candidate for the Know-Nothing Party in 1856.

The Know-Nothing Party received 8 electoral votes in the 1856 presidential election.

The Know-Nothing Party secured approximately 21.5% of the popular vote in the 1856 presidential election.

![Speech on [!] Hon, Wm. Barksdale, of Mississippi, on the Presidential Election 1856 Leather Bound](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)