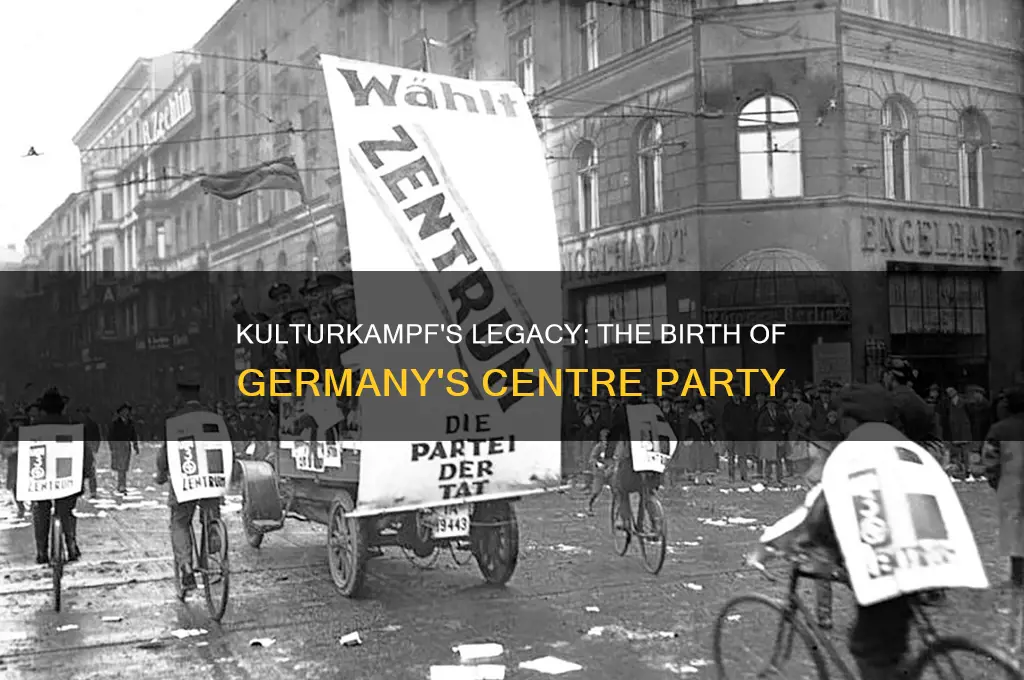

The Kulturkampf, a series of policies enacted by Otto von Bismarck in the 1870s to curb the influence of the Catholic Church in the newly unified German Empire, had profound political repercussions. While it did not directly give rise to a new political party, it significantly strengthened the *Zentrumspartei* (German Centre Party), a Catholic political party that had already been established in 1870. The Kulturkampf’s anti-Catholic measures, such as the expulsion of Jesuits and the introduction of state control over Church affairs, rallied Catholics in opposition, solidifying the Centre Party as a major political force. By uniting Catholics across regions and social classes, the Kulturkampf inadvertently bolstered the party’s influence, making it a key player in German politics for decades to come.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Center Party Formation: Kulturkampf opposition led to the rise of the German Centre Party

- Catholic Mobilization: Catholics united politically, strengthening the Center Party’s base

- Anti-Liberal Sentiment: Reaction to Bismarck’s policies fueled conservative Catholic political organization

- Religious Identity: Kulturkampf highlighted religion as a political rallying point

- Bismarck’s Backlash: His anti-Catholic measures inadvertently empowered the Center Party

Center Party Formation: Kulturkampf opposition led to the rise of the German Centre Party

The Kulturkampf, a bitter struggle between the Prussian-led German Empire and the Catholic Church in the 1870s, inadvertently sowed the seeds of a new political force. This conflict, marked by state attempts to curb the Church's influence, alienated a significant portion of the Catholic population. In response, Catholics mobilized politically, leading to the formation of the German Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei) in 1870. This party emerged as a direct consequence of the Kulturkampf, uniting Catholics under a common banner to defend their religious and political interests.

The Centre Party's formation was a strategic response to the Kulturkampf's repressive measures, such as the May Laws, which aimed to limit the Church's role in education and appointments. Catholics, feeling marginalized and threatened, sought a political platform to counter these attacks. The party's creation was not merely a defensive move but also a proactive effort to secure representation in the Reichstag and influence national policy. By organizing politically, Catholics aimed to protect their rights and ensure their voice was heard in the newly unified German Empire.

Analyzing the Centre Party's rise reveals its unique position in German politics. Unlike other parties, it was not defined by a single ideology but by its commitment to Catholic interests. This focus allowed it to attract a diverse range of supporters, from conservative rural Catholics to more progressive urban adherents. The party's ability to bridge these divides was crucial to its success and longevity. It became a significant force in the Reichstag, often holding the balance of power and influencing legislation on issues ranging from education to social welfare.

The Centre Party's impact extended beyond its immediate goals. By providing a political home for Catholics, it fostered a sense of unity and solidarity among a group that had felt increasingly isolated. This unity was instrumental in shaping German politics, as the party became a key player in coalition-building and governance. Its influence was particularly notable during the Weimar Republic, where it played a pivotal role in stabilizing the fragile democracy. The party's legacy underscores the importance of religious and cultural identity in political mobilization and the enduring impact of historical conflicts on political landscapes.

Instructively, the Centre Party's formation offers a blueprint for minority groups seeking political representation. It demonstrates the power of organizing around a shared identity and the potential for such movements to shape national politics. For modern political activists, the lesson is clear: unity and strategic mobilization can counter marginalization and secure a place at the decision-making table. The Centre Party's story is a testament to the resilience of communities under pressure and their ability to transform adversity into political strength.

Uniting Principles: Core Beliefs Shared by Both Political Parties

You may want to see also

Catholic Mobilization: Catholics united politically, strengthening the Center Party’s base

The Kulturkampf, a bitter struggle between the Prussian-led German Empire and the Catholic Church in the 1870s, had unintended consequences. Otto von Bismarck's attempt to curb the Church's influence through restrictive laws instead galvanized Catholics into political action. This mobilization directly contributed to the rise and strengthening of the Centre Party (Zentrum), a force that would shape German politics for decades.

Here's how it unfolded:

A Spark Ignites: Bismarck's Kulturkampf measures, including the expulsion of Jesuits, state control over education, and restrictions on religious practices, were seen as a direct attack on Catholic identity. Local Catholic communities, previously politically fragmented, found common ground in their opposition to these measures. Parish networks became hubs for political discussion and organization, fostering a sense of solidarity and shared purpose.

This grassroots movement, fueled by outrage and a desire to protect their faith, laid the groundwork for a unified Catholic political voice.

From Resistance to Representation: The Centre Party, founded in 1870, initially lacked a strong base. The Kulturkampf provided the catalyst it needed. Catholic leaders, priests, and laypeople rallied behind the party, seeing it as the primary vehicle to defend their rights and interests. The party's platform, which emphasized religious freedom, autonomy for the Church, and social justice, resonated deeply with Catholics across social strata.

Strength in Numbers: The Kulturkampf effectively transformed the Centre Party from a marginal group into a significant political force. Catholic voters, mobilized by their shared experience of persecution, turned out in droves, solidifying the party's position in the Reichstag. This newfound strength allowed the Centre Party to negotiate with Bismarck, ultimately leading to a compromise and the easing of Kulturkampf measures in the late 1870s.

Legacy of Unity: The experience of the Kulturkampf left a lasting imprint on German Catholicism. The Centre Party, born out of this struggle, became a powerful advocate for Catholic rights and a key player in shaping German politics. Its success demonstrated the power of political mobilization based on shared religious identity, a lesson that would resonate in other contexts throughout history.

Texas Urbanization: Shifting Political Landscapes and Party Dynamics

You may want to see also

Anti-Liberal Sentiment: Reaction to Bismarck’s policies fueled conservative Catholic political organization

Otto von Bismarck's Kulturkampf, a series of policies aimed at curbing the influence of the Catholic Church in Prussia, ignited a fierce backlash that reshaped the political landscape. This anti-liberal sentiment, fueled by perceived attacks on religious autonomy, became the crucible for the emergence of a distinct political force: the Zentrumspartei, or the German Centre Party.

Far from being a mere reactionary movement, the Zentrumspartei represented a calculated response to Bismarck's centralizing, secularizing agenda. Catholic leaders, recognizing the threat to their institutional power and cultural identity, mobilized their vast network of parishes, schools, and associations. This grassroots organization, coupled with the charismatic leadership of figures like Ludwig Windthorst, transformed religious grievance into a potent political platform.

The party's platform was a unique blend of conservatism and pragmatism. While staunchly defending the Church's prerogatives, the Zentrumspartei also advocated for social welfare policies, appealing to the working-class Catholic base. This strategic positioning allowed them to carve out a significant space in the Reichstag, becoming a pivotal swing vote in the late 19th century.

The Kulturkampf, ironically, achieved the opposite of its intended effect. Instead of marginalizing Catholicism, it catalyzed the creation of a resilient political entity that would shape German politics for decades. The Zentrumspartei's legacy extends beyond its immediate historical context, offering a compelling case study in how religious identity can be harnessed for political mobilization, even within a secularizing state.

Why Political Pundits Often Miss the Mark: Unraveling the Errors

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Religious Identity: Kulturkampf highlighted religion as a political rallying point

The Kulturkampf, a 19th-century conflict between the German Empire and the Catholic Church, inadvertently transformed religious identity into a potent political tool. By targeting Catholic institutions and clergy, Otto von Bismarck’s policies alienated a significant portion of the population, unifying Catholics in opposition. This backlash crystallized around the *Zentrumspartei* (German Centre Party), a political entity founded in 1870 to defend Catholic interests. The party’s rise underscores how religious identity, when threatened, can galvanize communities into organized political action.

Consider the mechanics of this transformation. Bismarck’s measures, such as the *Falk Laws* (1871–1875), restricted Catholic education, clergy appointments, and religious practices. These attacks on institutional autonomy fostered a siege mentality among Catholics, who began to view their faith not just as a spiritual matter but as a cultural and political identity under assault. The *Zentrumspartei* capitalized on this sentiment, framing its mission as the protection of Catholic rights against state overreach. This strategic alignment of religion and politics demonstrates how external pressure can convert a passive religious demographic into an active political force.

The *Zentrumspartei*’s success lay in its ability to bridge the gap between religious doctrine and political pragmatism. By advocating for religious freedom, the party attracted not only devout Catholics but also those who saw the Kulturkampf as an attack on individual liberties. This broad appeal allowed the party to become a significant player in the *Reichstag*, influencing policy and coalition-building for decades. Its longevity highlights the enduring power of religious identity as a political rallying point, even in an increasingly secularizing society.

To replicate this dynamic in contemporary contexts, political movements must identify and address perceived threats to religious or cultural identities. For instance, framing policies as defenses of religious freedom—rather than purely theological arguments—can mobilize diverse constituencies. Practical steps include fostering alliances between religious leaders and political strategists, leveraging grassroots networks, and utilizing media to amplify narratives of persecution or resistance. However, caution is necessary: overemphasizing religious identity can alienate non-religious voters or exacerbate divisions. The key is to balance identity politics with inclusive messaging that resonates beyond the core religious base.

In conclusion, the Kulturkampf’s legacy reveals how religious identity, when politicized, can shape electoral landscapes and institutional structures. The *Zentrumspartei*’s emergence as a counterforce to state secularization illustrates the transformative potential of uniting faith with political action. For modern political movements, this historical example offers both a blueprint and a warning: religious identity is a powerful mobilizing force, but its effectiveness depends on strategic framing and broad appeal.

The Rise of Mass Politics: A Historical Turning Point

You may want to see also

Bismarck’s Backlash: His anti-Catholic measures inadvertently empowered the Center Party

Otto von Bismarck's Kulturkampf, a series of anti-Catholic measures implemented in the 1870s, was intended to curb the influence of the Catholic Church in the newly unified German Empire. However, this aggressive campaign had an unintended consequence: it galvanized Catholic resistance and ultimately empowered the Center Party (Zentrum), a political force that would become a significant player in German politics for decades.

The Spark of Resistance: Bismarck's measures, which included the expulsion of Jesuits, state control over church appointments, and the abolition of religious exemptions, were seen as a direct attack on Catholic identity. This provoked a strong backlash, particularly in predominantly Catholic regions like Bavaria and the Rhineland. Catholics, feeling marginalized and threatened, rallied around their faith and sought political representation to protect their interests.

The Center Party, founded in 1870, initially focused on defending Catholic rights. However, Bismarck's Kulturkampf provided the party with a powerful mobilizing issue. By framing the struggle as one of religious freedom against state oppression, the Center Party gained widespread support among Catholics, transforming itself from a niche group into a mass movement.

A Political Miscalculation: Bismarck's strategy backfired spectacularly. His attempt to weaken the Catholic Church's influence only served to strengthen its political arm. The Center Party's success in the 1874 Reichstag elections, where it emerged as the second-largest party, demonstrated the extent of Catholic solidarity. This forced Bismarck to reconsider his approach, eventually leading to a reconciliation with the Vatican in the late 1870s.

Legacy of the Backlash: The Kulturkampf's unintended consequence was the creation of a powerful and enduring political force. The Center Party, born out of resistance to Bismarck's anti-Catholic policies, became a key player in German politics, advocating not only for Catholic rights but also for social reforms and parliamentary democracy. Its influence extended well beyond the immediate aftermath of the Kulturkampf, shaping German political landscape until the rise of the Nazi regime.

Bismarck's miscalculation serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of religious persecution and the potential for unintended consequences in political maneuvering. The Center Party's rise demonstrates the power of religious identity in shaping political movements and the ability of marginalized groups to organize and assert their rights in the face of oppression.

The Great Political Shift: Did Party Ideologies Swap in the 1930s?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Kulturkampf, a conflict between the German Empire and the Catholic Church, indirectly contributed to the rise of the Centre Party (Zentrum), a Catholic political party in Germany.

The primary goal of the Kulturkampf was to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church in Germany, particularly by limiting its control over education and civil matters.

The Kulturkampf united German Catholics in opposition to Otto von Bismarck's policies, leading to the formation of the Centre Party as a political force to defend Catholic interests.

Yes, the Centre Party gained substantial support during the Kulturkampf, becoming a major political party in the German Reichstag by representing Catholic voters.

The Kulturkampf solidified the Centre Party's role as a key political player in Germany, ensuring its longevity as a representative of Catholic and minority interests until the rise of the Nazi regime.