Adolf Hitler played a pivotal role in organizing and reunifying the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. Founded in 1919 as the German Workers' Party, Hitler joined the group in 1919 and quickly rose to prominence, becoming its leader by 1921. Under his leadership, the party was renamed the NSDAP and transformed into a powerful political force, blending extreme nationalism, antisemitism, and authoritarianism. After its decline following the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Hitler reorganized and reunified the party upon his release from prison in 1924, laying the groundwork for its eventual rise to power in 1933.

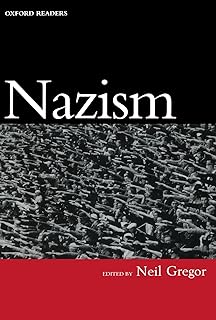

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Hitler's Role in the Nazi Party

Adolf Hitler's role in the Nazi Party was transformative, turning a fringe group into a dominant political force in Germany. Initially, the party, known as the German Workers' Party (DAP), was a small, nationalist organization with vague anti-Semitic and anti-Marxist ideals. Hitler joined in 1919 and quickly distinguished himself as a charismatic orator, capable of galvanizing audiences with his fiery rhetoric. By 1921, he had assumed leadership, renaming the party the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly referred to as the Nazi Party. This marked the beginning of his systematic reorganization and expansion of the party's structure, ideology, and appeal.

Hitler's organizational prowess was evident in his creation of a hierarchical party system designed to consolidate power. He established the *Sturmabteilung* (SA), a paramilitary wing, to intimidate opponents and maintain order at rallies. Later, he formed the *Schutzstaffel* (SS), an elite guard that became a tool for enforcing his will within and outside the party. These groups, combined with his appointment of loyalists to key positions, ensured that the Nazi Party operated as an extension of his personal authority. His ability to unify disparate factions within the party under a single vision was critical to its growth, as he balanced the demands of radical ideologues and pragmatic opportunists.

Ideologically, Hitler's role was to crystallize the party's platform around his own extremist beliefs. He articulated a vision of racial purity, national revival, and territorial expansion, encapsulated in his manifesto *Mein Kampf*. His ideas, though rooted in conspiracy theories and pseudoscience, resonated with a population disillusioned by economic hardship and the perceived humiliations of the Treaty of Versailles. By framing the Nazi Party as the sole defender of German honor and prosperity, Hitler created a cult of personality that made the party inseparable from his leadership. This ideological coherence, combined with his ability to exploit public grievances, was central to the party's rise.

A critical aspect of Hitler's role was his strategic use of propaganda and mass mobilization. He understood the power of symbolism, adopting the swastika as the party emblem and staging elaborate rallies that blended political theater with military precision. Joseph Goebbels, appointed as propaganda minister, amplified Hitler's message through newspapers, radio, and film, ensuring that the Nazi Party dominated public discourse. Hitler's mastery of spectacle, coupled with his promise to restore Germany to greatness, attracted millions of followers, transforming the party from a marginal group into a mass movement.

In conclusion, Hitler's role in the Nazi Party was not merely that of a leader but that of its architect and embodiment. He organized and reunified the party by imposing a rigid structure, unifying its ideology, and leveraging propaganda to mobilize the masses. His ability to merge personal charisma with political strategy made the Nazi Party a vehicle for his totalitarian ambitions. Without Hitler, the party would likely have remained a minor faction; with him, it became the instrument of one of history's most devastating regimes. Understanding his role is essential to comprehending how a single individual can reshape a political organization and, in turn, alter the course of history.

Crafting a Powerful Identity: Naming Your New Political Party Strategically

You may want to see also

Reunification of Nationalist Factions

Adolf Hitler's rise to power was significantly marked by his ability to organize and reunify disparate nationalist factions under the banner of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. This reunification was not merely a political maneuver but a strategic consolidation of fragmented right-wing groups, each with its own grievances and ideologies. By the early 1920s, Germany was a fertile ground for nationalism, fueled by the humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles, economic instability, and widespread discontent. Hitler recognized the potential in uniting these factions, leveraging their shared hatred of communism, democracy, and the perceived "other" to forge a cohesive movement.

The process of reunification began with Hitler's leadership of the NSDAP, which he joined in 1919 and quickly rose to prominence within. Initially, the party was one of many nationalist groups vying for influence. However, Hitler's charismatic oratory and ability to articulate a vision of national revival resonated with a broad spectrum of nationalists, from disillusioned veterans to middle-class conservatives. He strategically absorbed smaller factions, such as the German National People's Party (DNVP) and various paramilitary groups like the Sturmabteilung (SA), into the Nazi Party's orbit. This was not always a peaceful process; it involved negotiations, coercion, and even violence to eliminate rivals and centralize power.

A key tactic in Hitler's reunification strategy was the exploitation of shared enemies. He framed the Nazis as the only true defenders of German honor against communism, liberalism, and the alleged Jewish conspiracy. This narrative appealed to a wide range of nationalists, from radical anti-Semites to moderate conservatives who feared the rise of the left. By presenting the NSDAP as the unifying force for all Germans, Hitler effectively marginalized competing factions and positioned himself as the indispensable leader of the nationalist movement.

Practical steps in this reunification included the Harzburg Front of 1931, a coalition of right-wing groups that temporarily aligned under Nazi leadership. While this alliance was short-lived, it demonstrated Hitler's ability to bridge ideological divides within the nationalist camp. Another critical move was the Machtergreifung (seizure of power) in 1933, which solidified the Nazis' dominance by eliminating political opposition and consolidating control over the state. This period also saw the suppression of internal dissent within the party, ensuring that all nationalist factions operated under Hitler's undisputed authority.

In conclusion, Hitler's reunification of nationalist factions was a masterclass in political manipulation and strategic organization. By identifying common grievances, exploiting shared enemies, and leveraging his personal charisma, he transformed the NSDAP from one of many nationalist groups into the dominant force in German politics. This reunification was not just about ideology but about creating a unified movement capable of seizing and maintaining power. The lessons from this historical episode underscore the dangers of unchecked nationalism and the importance of vigilance against divisive, authoritarian ideologies.

Unveiling Political Parties: Surprising True Facts You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Founding of the NSDAP in 1920

The German Workers' Party (DAP), a small and relatively obscure political group, became the crucible for Adolf Hitler's rise to power. In 1919, Hitler, then a corporal in the German army, was sent to infiltrate the DAP by the Reichswehr, Germany's post-World War I military. What he found was a party ripe for transformation, its members disgruntled by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and seeking a scapegoat for Germany's woes. Recognizing the potential, Hitler joined the party and quickly began to reshape it according to his own extremist vision.

Hitler's organizational skills and charismatic oratory were instrumental in the DAP's metamorphosis into the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. In February 1920, he unveiled the party's 25-point program, a mix of nationalist, anti-Semitic, and socialist ideas designed to appeal to a broad spectrum of disillusioned Germans. The program promised everything from the abolition of the Versailles Treaty to the nationalization of industries, all while blaming Germany's problems on Jews and Marxists. This platform, coupled with Hitler's ability to galvanize crowds, attracted a growing number of followers, transforming the NSDAP from a fringe group into a significant political force.

The founding of the NSDAP in 1920 marked the beginning of Hitler's systematic effort to reunify and radicalize Germany's right-wing movements. He understood that strength lay in unity and set out to absorb smaller nationalist groups into the NSDAP. By 1921, he had consolidated his position as the party's undisputed leader, changing its name to reflect his vision of a national socialist movement. This period also saw the establishment of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the party's paramilitary wing, which played a crucial role in intimidating opponents and enforcing Nazi ideology.

Practical lessons from this historical moment are clear: the rise of extremist movements often begins with the exploitation of societal discontent. Hitler's success in organizing and reunifying the NSDAP hinged on his ability to channel widespread frustration into a cohesive, albeit dangerous, political agenda. For modern observers, this serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of addressing legitimate grievances before they are co-opted by demagogues. Vigilance against the erosion of democratic norms and the early identification of extremist ideologies remain essential in preventing history from repeating itself.

Is It Polite to Ask Who Else Is Coming to the Party?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Beer Hall Putsch and Party Revival

The Beer Hall Putsch of November 1923 marked a turning point for Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), though not in the way he initially intended. This failed coup attempt against the Weimar Republic government in Bavaria was a bold but ill-fated move that landed Hitler in prison and temporarily crippled the party. However, it also laid the groundwork for his eventual rise to power by transforming him into a national figure and providing a platform for his ideological revival.

Analytically, the putsch itself was a tactical disaster. Hitler, along with Erich Ludendorff and other nationalist leaders, seized a beer hall in Munich, declared a revolution, and attempted to march on Berlin. The local authorities quickly suppressed the uprising, and Hitler was arrested and charged with treason. The NSDAP was banned, and its leadership scattered. Yet, the trial that followed turned into a propaganda victory for Hitler. He used the courtroom as a stage, delivering speeches that garnered widespread attention and sympathy, particularly among right-wing circles. This exposure was invaluable, as it introduced Hitler to a broader audience and framed him as a martyr for the nationalist cause.

Instructively, the aftermath of the putsch forced Hitler to rethink his strategy. During his nine-month imprisonment, he dictated *Mein Kampf*, a manifesto outlining his ideology and future plans. This period of reflection and writing allowed him to refine his message and consolidate his vision for the party. Upon his release, Hitler focused on rebuilding the NSDAP legally, recognizing that a violent overthrow of the government was premature. He reorganized the party, emphasizing discipline, propaganda, and mass mobilization, which became hallmarks of its revival.

Persuasively, the revival of the NSDAP after the putsch demonstrates the power of narrative and resilience in political movements. Hitler’s ability to turn defeat into a stepping stone highlights the importance of adaptability and the strategic use of setbacks. By portraying the putsch as a heroic struggle against a corrupt system, he rallied disaffected Germans to his cause. The party’s resurgence was not just organizational but also psychological, tapping into the frustrations of a nation grappling with economic hardship and political instability.

Comparatively, the Beer Hall Putsch and its aftermath contrast sharply with other failed revolutionary attempts in history, which often led to the complete dissolution of the movements involved. Hitler’s ability to reunify and strengthen the NSDAP after such a public failure is a unique case study in political survival. It underscores the role of charismatic leadership, ideological clarity, and the exploitation of societal grievances in transforming a marginalized group into a dominant political force.

Practically, the lessons from this episode extend beyond historical analysis. For modern political organizers, it serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of premature action and the importance of building a robust organizational foundation. It also highlights the need to balance ideological purity with pragmatic strategies, as Hitler’s shift from insurrection to legal tactics ultimately enabled his rise. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for anyone studying the mechanics of political revival and the conditions that allow extremist movements to thrive.

One-Party Rule: Exploring Nations Where Voting for Alternatives is Forbidden

You may want to see also

Ideological Consolidation Under Hitler's Leadership

Adolf Hitler's rise to power was inextricably linked to his role in organizing and reunifying the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. Under his leadership, the party transformed from a fringe group into a dominant political force, achieving ideological consolidation that became the backbone of its authoritarian regime. This process was not merely about unifying disparate factions but about forging a singular, radical worldview that permeated every level of German society.

The first step in Hitler's ideological consolidation was the centralization of power within the NSDAP. By eliminating internal rivals, such as Gregor Strasser, who advocated for a more socialist agenda, Hitler ensured that the party's ideology aligned exclusively with his vision of racial nationalism and anti-Semitism. This purge, culminating in the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, sent a clear message: dissent would not be tolerated. The party's structure became hierarchical, with Hitler at its apex, embodying the principle of *Führerprinzip* (leader principle), which demanded absolute obedience.

Hitler's consolidation extended beyond the party ranks to reshape public consciousness. Through propaganda orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi regime saturated Germany with its ideology. The Nuremberg Rallies, for instance, were not just political events but spectacles designed to instill awe and loyalty. Schools, media, and cultural institutions were weaponized to indoctrinate citizens, particularly the youth, through organizations like the Hitler Youth. Even language was manipulated; terms like *Volksgemeinschaft* (people's community) fostered a false sense of unity while excluding Jews, Romani, and other "undesirable" groups.

A critical aspect of this consolidation was the merger of state and party. After becoming Chancellor in 1933, Hitler systematically dismantled democratic institutions, culminating in the Enabling Act, which granted him dictatorial powers. The NSDAP became the only legal political party, and its ideology was enshrined in law. This fusion ensured that opposition was not just discouraged but criminalized, as evidenced by the establishment of the Gestapo and concentration camps to suppress dissent.

Finally, Hitler's ideological consolidation was underpinned by a cult of personality. He was portrayed as the savior of Germany, a figure destined to restore its greatness. This mythos was reinforced through carefully curated public appearances, speeches, and even his personal lifestyle. By equating himself with the nation, Hitler ensured that loyalty to him was synonymous with loyalty to Germany. This psychological manipulation was so effective that even as the regime's policies led to war and devastation, many Germans remained committed to the Nazi cause.

In conclusion, Hitler's ideological consolidation within the NSDAP was a multifaceted process that combined political maneuvering, propaganda, institutional control, and personality cultism. It was not merely about organizing a party but about creating a totalitarian system where dissent was impossible, and the party's ideology became the only truth. This consolidation laid the groundwork for the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust, serving as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked authoritarianism.

Florida Politics Unveiled: Key Players Shaping the Sunshine State's Future

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hitler organized and reunified the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party.

Hitler took control of the Nazi Party in 1921, becoming its leader (Führer) after rejoining the party following his release from prison.

The original name was the German Workers' Party (DAP), founded in 1919. Hitler renamed it the NSDAP in 1920.

After the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, the Nazi Party was banned. Hitler reorganized it in 1925 after his release from prison, reunifying its factions under his leadership.

The Nazi Party served as the political vehicle for Hitler’s ideology, helping him gain support through propaganda, mass rallies, and promises of national revival, ultimately leading to his appointment as Chancellor in 1933.