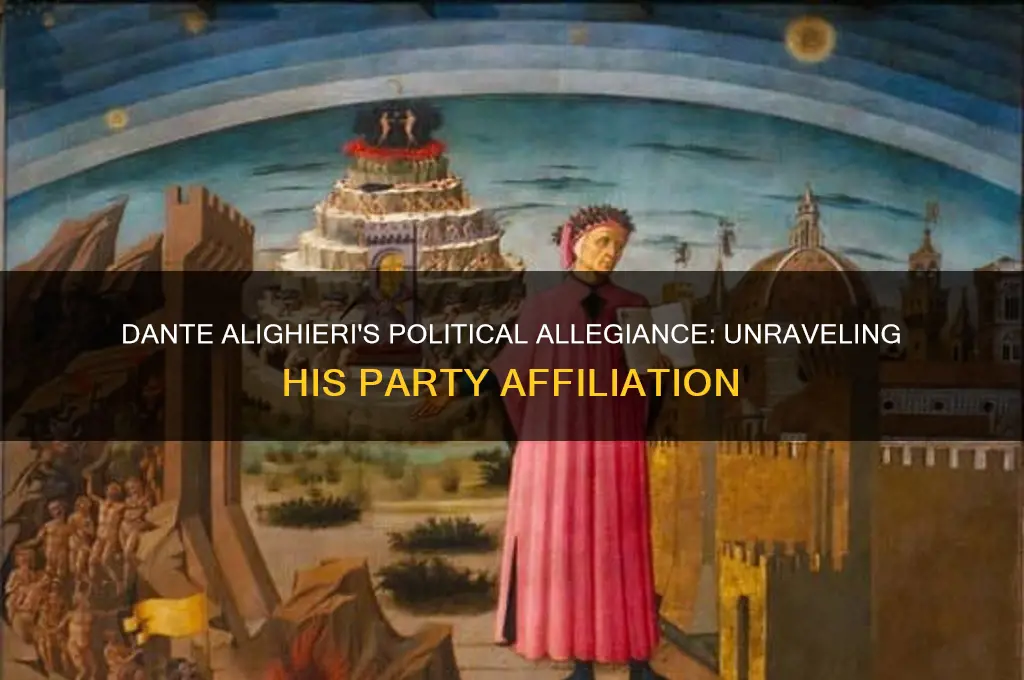

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, lived during a tumultuous period in late medieval Florence marked by intense political strife between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. The Guelphs, who supported the authority of the Pope, and the Ghibellines, who aligned with the Holy Roman Emperor, dominated Florentine politics. Dante himself was a member of the Guelph faction, though his views were complex and evolved over time. Initially part of the White Guelphs, who opposed papal interference in Florentine affairs, he later faced exile when the Black Guelphs, more aligned with the Pope, gained power. This political turmoil profoundly influenced his life and work, shaping his perspectives on governance, morality, and the human condition.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Affiliation | Dante Alighieri was associated with the Guelf (Guelph) party. |

| Faction within Guelfs | He belonged to the White Guelf faction, which opposed papal interference in Florentine politics. |

| Ideological Stance | Supported Florentine autonomy and resisted the influence of the Pope (Black Guelfs). |

| Role in Politics | Served as a prior (city council member) in Florence in 1300. |

| Exile | Exiled from Florence in 1302 due to political conflicts between the White and Black Guelfs. |

| Influence on Works | His political experiences and exile deeply influenced his writings, including The Divine Comedy. |

| Historical Context | Active during the late 13th and early 14th centuries in Florence, a period of intense political and factional strife. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dante's Political Affiliation: Unclear, but he supported the White Guelphs during his time in Florence

- White Guelphs vs. Black Guelphs: Dante aligned with the White faction, opposing papal influence

- Exile and Politics: Dante's exile from Florence shaped his political views and writings

- Dante's Views on Governance: He favored a balanced, imperial authority over factional rule

- Influence of Party Politics: Dante's works reflect his experiences with Florence's political divisions

Dante's Political Affiliation: Unclear, but he supported the White Guelphs during his time in Florence

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, lived during a tumultuous period in Florentine politics. While his exact political affiliation remains unclear, historical records and his writings suggest he was closely aligned with the White Guelphs during his time in Florence. This faction, one of the two dominant Guelph factions, advocated for a balance between papal and imperial authority, a stance that resonated with Dante’s own political philosophy. Understanding his support for the White Guelphs requires examining the context of 13th-century Florence, where political allegiances were often fluid and deeply tied to broader religious and regional conflicts.

To grasp Dante’s political leanings, consider the Guelph-Ghibelline divide that dominated medieval Italian politics. The Guelphs supported the papacy, while the Ghibellines aligned with the Holy Roman Empire. Within the Guelphs, the White faction, which Dante supported, opposed the more radical Black Guelphs, who sought greater papal influence in Florence. Dante’s alignment with the Whites reflects his belief in a limited papal role in secular affairs, a view he later articulated in his political treatise *De Monarchia*. This nuanced position highlights his intellectual independence, as he did not blindly follow either extreme but sought a middle ground.

Dante’s exile from Florence in 1302, orchestrated by the Black Guelphs, underscores the consequences of his political choices. As a prior of Florence and a prominent White Guelph, he was targeted for his opposition to the Black faction’s dominance. His exile forced him to wander northern Italy, a period that profoundly influenced his writing and political thought. *The Divine Comedy*, for instance, contains veiled critiques of his political enemies and reflections on justice and governance, demonstrating how his personal experiences shaped his artistic and philosophical output.

While Dante’s support for the White Guelphs is well-documented, his broader political affiliation remains elusive. He was not a rigid partisan but a thinker who grappled with the complexities of his era. His advocacy for a universal monarchy under the Holy Roman Emperor, as outlined in *De Monarchia*, suggests a vision beyond Florentine factionalism. Yet, this idea was rooted in his experiences with the White Guelphs, who similarly sought stability through balanced authority. Thus, his political stance was both a product of his time and a precursor to his later, more expansive ideas.

In practical terms, understanding Dante’s political alignment offers insights into his worldview and the historical context of his works. For scholars and readers alike, recognizing his support for the White Guelphs helps decode the political undertones in *The Divine Comedy* and his other writings. It also serves as a reminder of the intricate relationship between politics and literature in medieval Italy. While Dante’s exact affiliation may remain unclear, his association with the White Guelphs provides a crucial lens through which to interpret his life and legacy.

Islam's Political Influence: Understanding Its Global and Cultural Significance

You may want to see also

White Guelphs vs. Black Guelphs: Dante aligned with the White faction, opposing papal influence

Dante Alighieri, the renowned Italian poet and author of *The Divine Comedy*, was deeply entangled in the political turmoil of 13th-century Florence. His allegiance lay with the White Guelphs, a faction that staunchly opposed the excessive influence of the papacy in Florentine affairs. This choice was not merely political but deeply ideological, reflecting Dante’s belief in the separation of church and state—a revolutionary idea in his time.

To understand Dante’s alignment, consider the broader context of Guelph and Ghibelline rivalries. The Guelphs supported the papacy, while the Ghibellines backed the Holy Roman Empire. However, the Guelphs themselves fractured into White and Black factions. The Black Guelphs, led by figures like Corso Donati, embraced papal authority and sought to consolidate power through religious influence. In contrast, the White Guelphs, with Dante among them, advocated for Florentine autonomy and resisted papal interference. This division was not just about power but about the soul of Florence—whether it would remain a self-governing city or become a puppet of Rome.

Dante’s opposition to the Black Guelphs and their papal allies culminated in his exile from Florence in 1302. As a prior of Florence in 1300, he had worked to curb the influence of the Black faction, but his efforts were met with retaliation. The papacy, under Pope Boniface VIII, sided with the Blacks, leading to Dante’s condemnation as a traitor. His exile was a direct consequence of his unwavering commitment to the White Guelph cause, which he later immortalized in his writings. In *The Divine Comedy*, for instance, Boniface VIII is placed in the eighth circle of Hell, reserved for corrupt religious leaders—a clear statement of Dante’s disdain for papal overreach.

Practical takeaways from Dante’s alignment with the White Guelphs extend beyond medieval politics. His stance underscores the importance of balancing religious and secular authority, a principle still relevant in modern governance. For those studying political history or grappling with contemporary church-state debates, Dante’s example serves as a reminder that resistance to undue influence is often a matter of principle, not just power. To emulate his resolve, one might:

- Research historical precedents to understand the roots of current conflicts.

- Advocate for transparency in institutions that wield significant authority.

- Engage in dialogue across ideological divides to foster mutual understanding.

In essence, Dante’s allegiance to the White Guelphs was a bold assertion of civic independence against religious dominance. His legacy challenges us to question where power lies in our own societies and whether it serves the common good or the interests of a few. By aligning with the Whites, Dante did not just choose a faction—he chose a vision of Florence, and by extension, humanity, free from the shackles of unchecked authority.

Political Parties: Democracy's Allies or Adversaries in America?

You may want to see also

Exile and Politics: Dante's exile from Florence shaped his political views and writings

Dante Alighieri's exile from Florence in 1302 was a pivotal event that profoundly influenced his political views and literary works. Banished due to his involvement with the White Guelphs, a political faction opposed to the Black Guelphs who aligned with the Pope, Dante was stripped of his citizenship, property, and political rights. This abrupt severance from his homeland forced him to navigate a complex political landscape as a stateless intellectual, shaping his perspectives on governance, justice, and the moral responsibilities of leaders. His experiences in exile are not merely biographical footnotes but essential contexts for understanding the political undertones in his magnum opus, *The Divine Comedy*.

Analyzing Dante's political allegiances reveals a man deeply committed to the ideals of republicanism and the separation of church and state. Before his exile, he had been an active participant in Florentine politics, advocating for the autonomy of city-states against papal interference. However, his alignment with the White Guelphs, who sought to balance religious and secular authority, ultimately led to his downfall. Exile transformed his political thought from practical engagement to philosophical reflection. In *The Divine Comedy*, particularly in *Purgatorio* and *Paradiso*, Dante critiques corrupt political systems and envisions an ideal governance rooted in divine justice and moral integrity. His portrayal of Hell, for instance, is populated by figures who abused power, a thinly veiled commentary on the political realities of his time.

To understand Dante's political evolution, consider his treatment of historical and contemporary figures in his work. In *Inferno*, he reserves some of the harshest punishments for those who betrayed their cities or factions, reflecting his disdain for political treachery. Conversely, in *Paradiso*, he elevates figures like Justinian, who embody the fusion of imperial authority and divine law. This juxtaposition underscores Dante's belief in a universal order where political leadership must align with moral and spiritual principles. His exile, therefore, was not just a personal tragedy but a catalyst for articulating a vision of politics transcending the factionalism of Florence.

Practical takeaways from Dante's experience in exile include the importance of intellectual resilience in the face of political adversity. Despite his banishment, he continued to write, think, and engage with the political questions of his era. For modern readers, this serves as a reminder that political exile or marginalization need not silence one's voice. Instead, it can sharpen one's critique and deepen one's commitment to timeless principles. Dante's works encourage us to view politics not merely as a game of power but as a moral endeavor requiring integrity, justice, and a steadfast dedication to the common good.

In conclusion, Dante's exile from Florence was a crucible that refined his political thought and literary expression. His journey from a Florentine politician to a visionary poet illustrates how personal displacement can lead to profound intellectual and artistic contributions. By examining his life and works, we gain insights into the enduring interplay between politics, morality, and creativity, offering lessons that remain relevant in contemporary political discourse.

Riot, Punk, Politics: Unraveling the Radical Counterculture Movement

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dante's Views on Governance: He favored a balanced, imperial authority over factional rule

Dante Alighieri, the 14th-century Italian poet and philosopher, lived in a tumultuous era marked by political fragmentation and factional strife. Florence, his birthplace, was a battleground between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, factions aligned with the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively. Amid this chaos, Dante’s views on governance emerged not as a partisan allegiance but as a philosophical stance favoring unity and stability. He did not belong to a modern political party in the sense we understand today, but his writings reveal a clear preference for a balanced, imperial authority over the factional rule that plagued his time.

To understand Dante’s perspective, consider his masterpiece, *The Divine Comedy*, and his political treatise, *De Monarchia*. In these works, he advocates for a universal empire under the Holy Roman Emperor, independent of papal influence. This was not a call for autocracy but a vision of a centralized authority that could transcend local factions and ensure peace. Dante believed that such an empire would provide a moral and political framework, preventing the self-interest of city-states and factions from tearing society apart. His ideal governance was one where imperial power balanced local autonomy, creating harmony rather than dominance.

Dante’s disdain for factional rule is evident in his portrayal of Hell in *Inferno*, where he places political schemers and divisive figures in the lowest circles. He saw factions as the root of corruption, leading to personal gain at the expense of the common good. For instance, the Florentine Guelphs, split into the Black and White factions, exemplified the destructive nature of partisan politics. Dante’s exile from Florence by the Black Guelphs further solidified his conviction that factionalism bred injustice and instability. His solution was not to eliminate local governance but to place it under the umbrella of a higher, unifying authority.

Practically, Dante’s vision offers a timeless lesson in governance: the need for a balancing force to prevent the excesses of local or partisan interests. In modern terms, this could translate to federal systems where national authority complements state or regional autonomy. For leaders today, the takeaway is clear: fostering unity without suppressing diversity is essential. Dante’s imperial ideal, though rooted in medieval theology, underscores the importance of institutions that rise above narrow interests to serve the broader community.

In applying Dante’s ideas, one must caution against misinterpretation. His advocacy for imperial authority should not be conflated with modern imperialism or authoritarianism. Instead, it was a call for a moral and political framework that transcends division. For instance, international organizations like the United Nations or European Union reflect a similar aspiration for unity amidst diversity. By studying Dante’s views, we gain insight into how governance can navigate the tension between local autonomy and universal order, a challenge as relevant today as it was in his time.

Libertarian Platforms: Shaping the Evolution of US Political Parties

You may want to see also

Influence of Party Politics: Dante's works reflect his experiences with Florence's political divisions

Dante Alighieri, the 13th-century Italian poet, was deeply entangled in Florence’s fierce political landscape, a reality that profoundly shaped his works. A search reveals Dante’s alignment with the White Guelphs, a moderate faction opposed to the radical Black Guelphs. This division wasn’t merely ideological; it was personal, leading to his exile in 1302. His masterpiece, *The Divine Comedy*, isn’t just a theological journey—it’s a political statement, populated by contemporaries punished or rewarded based on their role in Florence’s strife. For instance, his placement of political rivals in Hell’s circles reflects his bitterness toward those who ousted him.

To understand Dante’s political influence, consider his use of allegory as a weapon. In *Inferno*, the character of Farinata degli Uberti, a Ghibelline leader, isn’t just a historical figure but a symbol of Florence’s fractured identity. Dante’s dialogue with Farinata—tense, respectful, yet critical—mirrors his own struggle to reconcile personal loyalty with political necessity. This isn’t mere storytelling; it’s a lesson in the consequences of division. For modern readers, it’s a reminder that literature can immortalize political conflicts, turning ephemeral struggles into timeless commentary.

If you’re analyzing Dante’s works through a political lens, start by mapping Florence’s factions: Guelphs (papal supporters) vs. Ghibellines (imperial supporters), further split into Whites and Blacks. Note how Dante’s exile forced him to write from an outsider’s perspective, granting him a unique vantage point. For instance, his depiction of Florence in *Purgatorio* isn’t nostalgic but critical, highlighting its moral decay. This approach allows readers to see how personal exile can sharpen political critique, a tactic still used by writers in repressive regimes today.

A practical takeaway: Dante’s experience teaches that political divisions aren’t just abstract—they shape art, identity, and legacy. For educators or students, pairing *The Divine Comedy* with historical accounts of Florence’s factions provides a richer understanding of both the text and its context. For writers, it’s a lesson in embedding political commentary subtly yet powerfully. Dante didn’t just write about Florence; he wrote *through* it, proving that literature can be both a mirror and a scalpel to societal wounds.

Finally, Dante’s party affiliation wasn’t just a footnote—it was the crucible of his creativity. His White Guelph stance wasn’t merely about power but about ideals: moderation, justice, and civic harmony. Yet, his works transcend his faction, offering universal insights into human nature. This duality—the specific and the universal—is what makes his political reflections enduring. Whether you’re a historian, a literature enthusiast, or a political observer, Dante’s story underscores how deeply personal stakes can fuel monumental art.

Divided We Stand: Understanding America's Political Party Polarization

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Dante Alighieri lived in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a time before modern political parties existed. However, he was aligned with the Guelph faction in Florence, which was a political and religious grouping supportive of the Papacy.

No, Dante Alighieri was not a Ghibelline. He was a Guelph, specifically a White Guelph, who opposed the more radical Black Guelphs and supported moderate papal influence in Florence.

Yes, Dante’s political affiliations deeply influenced his writings, particularly in *The Divine Comedy*. His exile from Florence by the Black Guelphs and his reflections on political and moral justice are central themes in his work.

The Guelphs were a significant part of Dante’s life, as he was an active member of the White Guelph faction. His involvement in Florentine politics led to his exile in 1302 when the Black Guelphs took control of the city.

Dante remained loyal to the White Guelphs throughout his life. However, his views evolved toward a more universal perspective, advocating for a unified Italy under imperial authority, as reflected in his later writings.

![Wiener Staatswissenschaftliche Studien. Sechster Band. Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri, pp. 2-152 [238-388] (German Edition)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41IHCYrmtBL._AC_UY218_.jpg)