Redlining, a discriminatory practice that systematically denied services or increased costs for residents in specific neighborhoods based on race or ethnicity, has its roots in policies established during the New Deal era of the 1930s. While not directly tied to a single political party, the creation and implementation of redlining were largely driven by the federal government under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, which was dominated by the Democratic Party. The Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored entity, developed color-coded maps that categorized neighborhoods by risk level, with predominantly African American and minority areas labeled as hazardous and outlined in red, effectively denying them access to fair housing loans and investment. Although the Democratic Party was responsible for these policies, the practice of redlining was perpetuated by both major parties and private institutions, embedding racial segregation and economic inequality into the fabric of American society for decades.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Redlining: New Deal policies under FDR's administration institutionalized racial housing segregation

- Role of the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC): HOLC maps codified redlining practices in the 1930s

- Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Policies: FHA reinforced redlining through discriminatory lending guidelines

- Democratic Party's New Deal Legacy: New Deal programs disproportionately excluded Black Americans from homeownership

- Republican Party's Stance: Republicans initially supported redlining but later shifted focus to deregulation

Origins of Redlining: New Deal policies under FDR's administration institutionalized racial housing segregation

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), established under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal in 1934, played a pivotal role in institutionalizing racial housing segregation through redlining. While the FHA aimed to stimulate the housing market and make homeownership more accessible, its policies explicitly discriminated against African Americans and other minority groups. The FHA's underwriting manuals provided guidelines for assessing the risk of mortgage loans, and these manuals explicitly warned against lending in neighborhoods with "inharmonious racial or nationality groups." This language effectively codified racial segregation, as neighborhoods with significant Black populations were deemed high-risk and outlined in red on maps—hence the term "redlining."

To understand the mechanics of redlining, consider the FHA's appraisal process. Appraisers were instructed to evaluate neighborhoods based on factors like racial composition, property values, and perceived stability. Areas with predominantly White populations received high ratings, while those with Black residents were systematically downgraded. For instance, a 1938 FHA manual stated, "If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes." This policy not only denied African Americans access to federally backed mortgages but also devalued their homes, perpetuating economic inequality. The result was a self-fulfilling prophecy: neighborhoods redlined by the FHA deteriorated due to lack of investment, further justifying discriminatory practices.

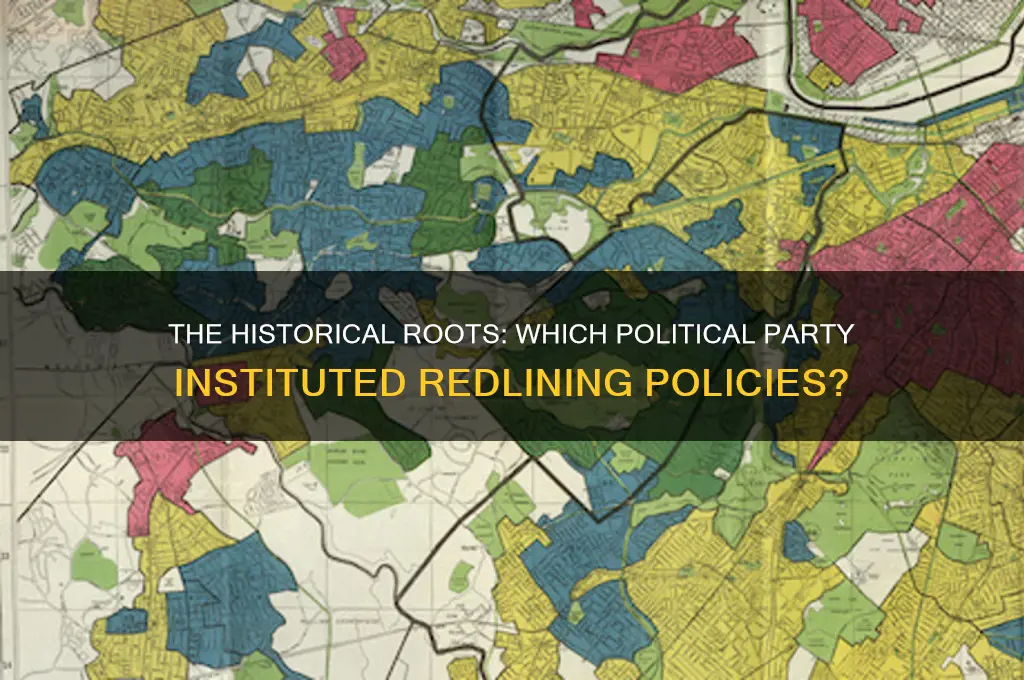

The Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), another New Deal agency, collaborated with the FHA to create "residential security maps" that categorized neighborhoods by risk. These maps, color-coded from green (best) to red (worst), became the blueprint for redlining. Redlined areas were denied access to loans, insurance, and development funds, while greenlined areas received substantial investment. This systemic discrimination was not an unintended consequence but a deliberate policy choice. For example, in cities like Chicago and Detroit, Black neighborhoods were consistently redlined, while adjacent White neighborhoods were greenlined, even when the latter had lower property values. This disparity highlights the racial, rather than economic, basis of redlining.

The legacy of these New Deal policies is still felt today. Redlining not only restricted African Americans' access to homeownership but also limited their ability to build intergenerational wealth. Studies show that redlined neighborhoods continue to struggle with higher poverty rates, poorer health outcomes, and underfunded schools. While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed explicit racial discrimination in housing, the damage caused by decades of redlining remains. Addressing this legacy requires targeted policies, such as reinvestment in historically redlined communities and reparations for affected families. By acknowledging the role of New Deal policies in creating redlining, we can work toward dismantling the systemic racism they institutionalized.

Walter Byers' Political Affiliation: Uncovering the NCAA President's Party Ties

You may want to see also

Role of the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC): HOLC maps codified redlining practices in the 1930s

The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), established in 1933 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, played a pivotal role in institutionalizing redlining. Tasked with refinancing home mortgages during the Great Depression, HOLC inadvertently created a system that would entrench racial and economic inequality for decades. By producing color-coded maps to assess neighborhood risk for mortgage lending, HOLC codified discriminatory practices that devalued communities of color, labeling them as "hazardous" for investment.

Analyzing HOLC’s methodology reveals its inherent bias. Neighborhoods with significant African American, immigrant, or working-class populations were systematically graded as high-risk, regardless of their actual economic stability. These maps, which assigned grades from "A" (green, best) to "D" (red, worst), became the blueprint for future lending practices. The redlined areas were denied access to loans, insurance, and investment, stifling their growth and perpetuating poverty. This government-backed system effectively segregated cities, shaping urban landscapes that still reflect these divisions today.

The consequences of HOLC’s redlining were far-reaching and deliberate. By restricting access to capital, redlined neighborhoods were unable to build wealth through homeownership, a cornerstone of middle-class stability. Meanwhile, greenlined areas, predominantly white, received favorable treatment, widening the racial wealth gap. This disparity was not an unintended outcome but a direct result of policies that prioritized racial homogeneity over economic fairness. HOLC’s maps became self-fulfilling prophecies, as disinvestment turned once-thriving communities into neglected zones.

To understand HOLC’s legacy, consider its impact on modern-day housing disparities. Studies show that redlined neighborhoods continue to struggle with lower property values, higher foreclosure rates, and limited access to amenities. For instance, a 2018 analysis found that 74% of redlined areas in major U.S. cities remain low-to-moderate income, compared to only 9% of greenlined areas. This persistence underscores the enduring power of HOLC’s policies, which were adopted by private lenders and reinforced by subsequent federal programs.

While HOLC was created under a Democratic administration, its redlining practices were not explicitly partisan but rather a reflection of the era’s systemic racism. However, the agency’s actions highlight how government policies can codify prejudice, shaping societal outcomes for generations. Dismantling redlining’s legacy requires acknowledging this history and implementing targeted interventions, such as community reinvestment programs and equitable lending policies. Only by confronting HOLC’s role can we begin to address the inequalities it helped create.

Comparing Political Stances: Which Party Advocates Stronger Gun Control?

You may want to see also

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Policies: FHA reinforced redlining through discriminatory lending guidelines

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), established in 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was designed to stabilize the housing market during the Great Depression. While its intent was to make homeownership more accessible, its policies inadvertently—and often deliberately—reinforced racial segregation through discriminatory lending guidelines. The FHA’s underwriting manuals explicitly categorized neighborhoods as desirable or undesirable based on racial composition, a practice that became a cornerstone of redlining. Neighborhoods with Black, Jewish, or immigrant populations were labeled high-risk, effectively denying residents access to federally backed mortgages.

Consider the FHA’s *Underwriting Manual* of 1936, which advised lenders to avoid areas with “inharmonious racial or nationality groups.” This language codified racial bias into federal policy, ensuring that minority neighborhoods were systematically excluded from economic opportunities. For instance, a predominantly Black neighborhood in Chicago or Detroit would be “redlined” on FHA maps, making it nearly impossible for residents to secure loans for home purchases or improvements. This not only perpetuated segregation but also devalued properties in these areas, creating a cycle of disinvestment that persists to this day.

The FHA’s policies were not merely passive reflections of societal prejudice; they actively shaped it. By steering investment toward white suburban developments—often referred to as “white flight” areas—the FHA subsidized the growth of racially homogenous communities while leaving urban minority neighborhoods to deteriorate. This dual approach effectively funneled federal resources into the hands of white homeowners, widening the racial wealth gap. For example, between 1934 and 1962, the FHA insured nearly 12 million home loans, with less than 2% going to non-white borrowers.

To understand the long-term impact, examine the data: neighborhoods redlined by the FHA in the mid-20th century remain disproportionately low-income and minority-dominated today. A 2018 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that 74% of redlined neighborhoods are still struggling economically, compared to only 14% of neighborhoods that received the highest FHA ratings. This legacy underscores how federal policies, rather than market forces alone, were instrumental in entrenching racial inequality in housing.

Practical steps to address this legacy include targeted reinvestment in historically redlined communities, such as through affordable housing initiatives and community development grants. Policymakers can also implement zoning reforms to promote mixed-income neighborhoods and combat the exclusionary practices that the FHA once championed. For individuals, supporting fair housing organizations and advocating for transparency in lending practices can help dismantle the systemic barriers erected by the FHA’s discriminatory guidelines. The FHA’s role in redlining serves as a stark reminder that policy decisions have lasting consequences—and that intentional, equitable solutions are required to undo them.

Exploring Finland's Political Landscape: Do Political Parties Exist There?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Democratic Party's New Deal Legacy: New Deal programs disproportionately excluded Black Americans from homeownership

The New Deal, a series of programs launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, aimed to lift the United States out of the Great Depression. While it provided economic relief and reshaped American society, its legacy is marred by racial disparities. One of the most significant consequences was the systemic exclusion of Black Americans from homeownership opportunities, a practice that laid the groundwork for modern redlining.

Consider the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), established in 1934 to stimulate the housing market. The FHA’s underwriting manual explicitly discouraged loans in neighborhoods with "inharmonious racial or nationality groups," effectively segregating Black Americans into underfunded, undervalued areas. This policy, known as redlining, was not merely a byproduct of private discrimination but a government-sanctioned practice. Similarly, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), another New Deal agency, graded neighborhoods based on racial composition, labeling predominantly Black areas as high-risk investments. These policies denied Black families access to the single largest source of wealth-building in the U.S.: home equity.

The consequences were profound and long-lasting. By 1940, only 24% of Black families owned homes compared to 45% of white families, a gap that persists today. The exclusion from homeownership also limited Black Americans’ access to quality education, healthcare, and economic mobility, as property values in redlined areas plummeted. This systemic disenfranchisement was not an unintended consequence but a deliberate design feature of New Deal programs, rooted in the Democratic Party’s compromise with Southern segregationists to secure legislative support.

To address this legacy, policymakers must confront the structural racism embedded in housing policies. Practical steps include targeted investments in historically redlined neighborhoods, down-payment assistance programs for first-time Black homebuyers, and reforms to eliminate discriminatory lending practices. Additionally, educating the public about the origins of housing inequality can foster accountability and drive systemic change. The New Deal’s exclusionary policies remind us that progress must be inclusive to be just.

Switching Political Parties in Oregon: A Simple Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Republican Party's Stance: Republicans initially supported redlining but later shifted focus to deregulation

The Republican Party's historical relationship with redlining is a complex narrative of initial support followed by a strategic shift. In the mid-20th century, Republicans, alongside Democrats, played a role in institutionalizing redlining through policies like the 1937 Housing Act, which effectively segregated neighborhoods by denying loans to minority communities. This era saw Republicans advocating for government intervention to maintain racial and economic homogeneity in housing markets. However, by the late 20th century, the party's stance evolved, pivoting away from direct support for redlining toward a broader agenda of deregulation. This shift was framed as a push for free-market principles, but it often perpetuated systemic inequalities by dismantling safeguards that could address redlining’s legacy.

To understand this transition, consider the Republican Party’s legislative actions. In the 1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, deregulation became a cornerstone of economic policy. While this approach aimed to reduce government control and stimulate growth, it also weakened institutions like the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which had been designed to combat redlining. By emphasizing deregulation, Republicans effectively reduced oversight in lending practices, allowing discriminatory behaviors to persist under the guise of market freedom. This shift highlights how the party’s priorities moved from active support of redlining to passive enablement through policy neglect.

A comparative analysis reveals the irony in the Republican Party’s evolution. Initially, their support for redlining was rooted in government intervention to enforce racial segregation. Later, their advocacy for deregulation ostensibly championed individual liberty but inadvertently allowed discriminatory practices to thrive unchecked. This duality underscores a recurring theme in the party’s approach to housing policy: a focus on short-term economic gains over long-term equity. For instance, while deregulation boosted financial institutions, it often left minority communities vulnerable to predatory lending and housing instability.

Practical implications of this shift are evident in the disparities that persist today. Communities of color, historically targeted by redlining, continue to face barriers to homeownership and wealth accumulation. For individuals navigating these challenges, understanding the Republican Party’s role provides context for advocating change. Steps like supporting policies that strengthen fair housing laws or engaging in local initiatives to address systemic inequities can counteract the lingering effects of redlining. Caution, however, must be exercised in assuming deregulation inherently benefits all; its impact often varies starkly across demographic lines.

In conclusion, the Republican Party’s stance on redlining—from active endorsement to indirect perpetuation through deregulation—reflects a broader ideological transformation. While the party’s shift may have been framed as a move toward economic freedom, its consequences for marginalized communities remain profound. Recognizing this history is crucial for crafting policies that not only address past injustices but also prevent their recurrence in the future.

Exploring Canada's Provincial Political Parties: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Redlining was not created by a single political party but was institutionalized through policies and practices implemented by both Democratic and Republican administrations, particularly during the New Deal era under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Yes, the Democratic Party, through the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) under the Roosevelt administration, played a significant role in institutionalizing redlining by creating maps that graded neighborhoods based on racial demographics, often denying loans to minority communities.

While redlining was primarily established under Democratic leadership, Republican administrations and policymakers did not actively dismantle these practices and often upheld or benefited from the discriminatory housing policies that resulted from redlining.

Yes, redlining was effectively a bipartisan issue, as both Democratic and Republican leaders and institutions contributed to or failed to address the discriminatory practices that segregated communities and denied opportunities to minority groups.