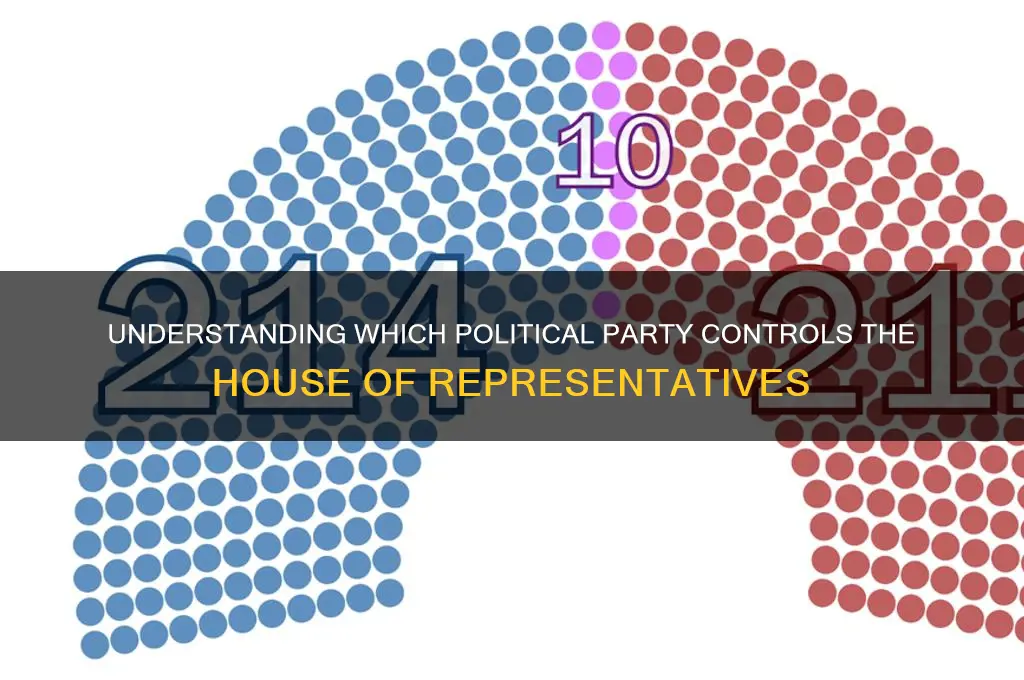

The composition of the House of Representatives in the United States Congress is directly influenced by the political party affiliations of its members, who are elected every two years. As of the most recent elections, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party dominate the House, with the majority party holding significant power in setting the legislative agenda, controlling committee assignments, and electing the Speaker of the House. The balance of power between these two parties shifts with each election cycle, reflecting the political priorities and sentiments of the American electorate. Understanding which party holds the majority in the House is crucial, as it determines the direction of key legislative initiatives and the overall political landscape in Washington, D.C.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Formation and evolution of the House of Representatives within the political party congress

- Leadership Roles: Key positions like Speaker and Majority Leader in the House structure

- Legislative Process: How bills are introduced, debated, and passed in the House

- Party Dynamics: Influence of political parties on House operations and decision-making

- Elections & Terms: House members' election process, term lengths, and reelection strategies

Historical Origins: Formation and evolution of the House of Representatives within the political party congress

The House of Representatives, a cornerstone of American democracy, was born from the Great Compromise of 1787, a pivotal moment in the Constitutional Convention. This compromise resolved a contentious debate between large and small states, creating a bicameral legislature where the House, with representation based on population, balanced the Senate's equal representation for each state. This foundational decision not only shaped the House's structure but also embedded it within the broader framework of political party congress, setting the stage for its evolution.

As the United States expanded, so did the House of Representatives, both in size and complexity. The Apportionment Act of 1911 fixed the number of representatives at 435, a figure that has remained constant despite significant population growth. This stability, however, belies the dynamic nature of the House within the political party congress. The evolution of political parties—from the early Federalists and Democratic-Republicans to today’s Democrats and Republicans—has profoundly influenced the House’s operations. Party caucuses and leadership structures emerged as essential mechanisms for organizing members, shaping legislative agendas, and maintaining party discipline, transforming the House into a highly partisan institution.

The role of the House within the political party congress has also been shaped by historical shifts in power and ideology. The Speaker of the House, for instance, evolved from a procedural role to a powerful partisan leader, often serving as the de facto head of the majority party. This transformation was particularly evident during the speakership of figures like Henry Clay and Tip O’Neill, who used the position to advance their party’s agenda. Similarly, the committee system, initially designed to streamline legislation, became a battleground for party influence, with committee chairs often selected based on seniority and party loyalty.

A comparative analysis reveals that the House’s integration into the political party congress contrasts with systems in other democracies. Unlike the British Parliament, where party discipline is nearly absolute, the House allows for more individual autonomy, though this has diminished over time. Similarly, while the German Bundestag operates on a proportional representation model, the House’s winner-take-all system reinforces party polarization. This unique blend of representation and partisanship has made the House both a reflection of and a contributor to America’s political landscape.

Practical tips for understanding the House’s role within the political party congress include studying key legislative battles, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, where party dynamics played a decisive role. Additionally, tracking party leadership elections and committee assignments provides insight into the internal power structures that drive the House’s agenda. For those interested in historical trends, examining shifts in party control—such as the Republican Revolution of 1994 or the Democratic wave of 2006—offers a window into how external political forces shape the House’s evolution. By focusing on these specifics, one can grasp the intricate relationship between the House of Representatives and the political party congress, a relationship that continues to define American governance.

Unveiling the Author: Who Penned the Political Diary Mystery?

You may want to see also

Leadership Roles: Key positions like Speaker and Majority Leader in the House structure

The Speaker of the House is the most powerful leadership role in the House of Representatives, wielding influence over both legislative agenda and party direction. Elected by the majority party, the Speaker presides over House debates, appoints committee chairs, and controls the flow of legislation. Historically, figures like Tip O’Neill (D-MA) and Newt Gingrich (R-GA) exemplify how the Speaker can shape policy and party identity. Unlike the Senate Majority Leader, the Speaker’s role is more ceremonial in some aspects but far more authoritative in others, as they act as the institutional leader of the House and the de facto leader of their party in the chamber.

The Majority Leader serves as the Speaker’s chief deputy, managing the legislative schedule and ensuring party cohesion on key votes. This role requires a blend of strategic thinking and political acumen, as the Majority Leader must navigate competing interests within the caucus while advancing the party’s agenda. For instance, Steny Hoyer (D-MD) and Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) have both held this position, demonstrating how the role demands both loyalty to the Speaker and the ability to independently rally support. While the Majority Leader lacks the Speaker’s institutional power, their success hinges on building relationships and maintaining party discipline.

Beyond the Speaker and Majority Leader, the Minority Leader plays a critical counterbalancing role, representing the opposition party’s interests in the House. This position requires a dual focus: blocking unfavorable legislation while positioning the minority party as a viable alternative. Notable Minority Leaders like Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) have used this role to fundraise, message, and prepare their party for potential majority status. Unlike the Majority Leader, the Minority Leader operates with fewer institutional tools, relying instead on procedural tactics and public outreach to influence outcomes.

Understanding these leadership roles reveals the House’s hierarchical structure and the dynamics of partisan power. The Speaker and Majority Leader form the backbone of the majority party’s strategy, while the Minority Leader acts as both adversary and shadow leader. Practical takeaways include recognizing how these roles shape legislative outcomes and how their occupants’ personalities and priorities can redefine party agendas. For instance, a Speaker with a strong ideological bent can push their party further left or right, while a pragmatic Majority Leader can broker compromises to secure victories.

In practice, observing these roles in action provides insight into the House’s operational rhythm. During critical votes, watch how the Majority Leader whips votes, the Speaker controls debate time, and the Minority Leader deploys procedural maneuvers. For those engaged in advocacy or policy work, understanding these dynamics can inform strategies for influencing legislation. For example, lobbying efforts might target the Majority Leader to secure floor time or the Minority Leader to build bipartisan support. Ultimately, these leadership roles are not just titles but levers of power that define the House’s function and direction.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Louisiana: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Legislative Process: How bills are introduced, debated, and passed in the House

The legislative process in the House of Representatives is a complex dance of procedure, persuasion, and power, where the majority party wields significant control. A bill’s journey begins with introduction, typically by a member of the House, who becomes its sponsor. This initial step is deceptively simple but hinges on strategic timing and alignment with the majority party’s agenda. For instance, a Democrat introducing a climate bill in a Democrat-controlled House has a higher chance of it being referred to a favorable committee, while a Republican sponsor might face procedural hurdles. The majority party’s leadership plays a pivotal role here, deciding which bills move forward and which languish in obscurity.

Once introduced, a bill is referred to a committee, where the real work begins. Committees are often chaired by members of the majority party, giving them the power to schedule hearings, invite witnesses, and amend the bill. This stage is both analytical and political; committees scrutinize the bill’s feasibility, cost, and impact, but their decisions are also influenced by party priorities. For example, a Republican-led committee might prioritize tax cuts, while a Democratic committee could focus on social welfare programs. The markup session, where amendments are proposed and voted on, is a critical juncture. Here, the majority party’s ability to shape the bill’s final form becomes evident, as they can outvote the minority to align the bill with their platform.

Debate on the House floor is the next step, but it’s tightly controlled by the majority party through a process called the “Rule.” The Rules Committee, dominated by the majority party, sets the terms of debate, including time limits and whether amendments are allowed. This control ensures the bill remains aligned with the party’s goals and minimizes disruptions from the minority. For instance, during a Democratic majority, the Rule might allow for amendments that strengthen environmental protections, while a Republican majority could restrict amendments to focus on fiscal conservatism. This stage is as much about messaging as it is about policy, with both parties using floor speeches to rally support and criticize opponents.

The final vote is where the majority party’s strength is most visible. With a simple majority (218 out of 435 votes), a bill passes the House. The majority party’s leadership works behind the scenes to whip votes, ensuring their members toe the party line. However, this isn’t always straightforward. Moderates or members from swing districts might defect if the bill is too extreme, while the minority party can exploit these divisions. For example, a Republican bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act might face resistance from moderate Republicans, requiring careful negotiation. Once passed, the bill moves to the Senate, but its House journey highlights the majority party’s dominance at every stage—from introduction to final vote.

Understanding this process reveals why control of the House is so fiercely contested. The majority party doesn’t just set the agenda; it shapes the very rules of the game. For citizens, this means that the party in power in the House has disproportionate influence over the laws that govern them. Practical tips for engagement include tracking bills through resources like Congress.gov, contacting representatives during the committee stage when amendments are still possible, and leveraging grassroots pressure during floor debates. Ultimately, the legislative process in the House is a masterclass in how procedural control translates into policy power.

Chile's Political Landscape: Understanding the Dominant Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Party Dynamics: Influence of political parties on House operations and decision-making

The U.S. House of Representatives is a battleground where political parties wield significant influence, shaping not just legislation but the very mechanics of how the chamber operates. Party dynamics dictate committee assignments, leadership roles, and even the physical seating arrangement on the House floor. Majority and minority parties negotiate power-sharing agreements, determining which bills get prioritized and which amendments receive floor time. This partisan structure ensures that the House functions as a reflection of the country’s political divide, with parties acting as both catalysts and gatekeepers of policy.

Consider the role of party leadership, such as the Speaker of the House, who is almost always a member of the majority party. The Speaker controls the legislative agenda, deciding which bills are brought to the floor for a vote. This power is not merely procedural; it is deeply political, as the Speaker’s decisions align with the party’s priorities. For instance, during the 117th Congress, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) prioritized bills on infrastructure and social spending, reflecting Democratic Party goals. Conversely, when Republicans hold the majority, their leadership tends to focus on issues like tax cuts and deregulation. This partisan control over the agenda underscores how party dynamics directly influence the House’s operational efficiency and policy outcomes.

Parties also enforce discipline through mechanisms like the whip system, which ensures members vote along party lines. Whips, appointed by party leaders, gauge support for legislation and persuade members to toe the party line. For example, during the Affordable Care Act debates in 2010, Democratic whips worked tirelessly to secure enough votes for passage, despite internal party divisions. This internal pressure can stifle individual representatives’ independence but ensures that the party’s platform is advanced cohesively. However, it also highlights the tension between party loyalty and constituent representation, as members must balance their party’s demands with the needs of their districts.

The influence of parties extends beyond voting behavior to the very culture of the House. Partisan polarization has intensified in recent decades, leading to a more adversarial environment. This is evident in the increased use of procedural tactics, such as filibusters and discharge petitions, which are often employed to block the opposing party’s agenda. For instance, during the 116th Congress, Republicans used procedural motions to delay Democratic-led bills, while Democrats countered with strategic committee assignments to advance their priorities. Such tactics illustrate how party dynamics not only shape decision-making but also create a climate where compromise is increasingly rare.

To navigate this partisan landscape effectively, representatives must master the art of intra-party negotiation and coalition-building. For example, moderates in both parties often form caucuses, like the Problem Solvers Caucus, to bridge the ideological gap and push for bipartisan solutions. These efforts, while challenging, demonstrate that party dynamics are not insurmountable barriers to cooperation. By understanding the mechanisms through which parties exert influence, members can strategically leverage their positions to advance legislation that aligns with both party goals and the public interest. This delicate balance is essential for the House to function as a responsive and effective legislative body.

Exploring Nations That Restrict the Number of Political Parties

You may want to see also

Elections & Terms: House members' election process, term lengths, and reelection strategies

Every two years, all 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are up for election, a process that shapes the political landscape and determines which party controls the chamber. Unlike the Senate, where members serve six-year terms, House members face reelection frequently, creating a dynamic and responsive legislative body. This biennial election cycle ensures that representatives remain accountable to their constituents, as their performance is regularly evaluated at the ballot box. The process begins with primaries, where party candidates are selected, followed by the general election in November. This rapid turnover contrasts sharply with other democratic institutions, making the House a barometer of public sentiment.

The election process for House members is governed by the Constitution, which sets eligibility requirements: candidates must be at least 25 years old, a U.S. citizen for seven years, and a resident of the state they represent. However, redistricting—the redrawing of congressional districts every decade—plays a pivotal role in shaping elections. Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating district boundaries for political advantage, can skew outcomes and entrench party control. For instance, in 2022, several states saw contentious redistricting battles that influenced the balance of power in the House. Understanding these structural factors is crucial for candidates and voters alike, as they directly impact the competitiveness of races.

Term lengths in the House are fixed at two years, a design intended to keep representatives closely tied to their constituents’ needs. This brevity, however, necessitates constant campaigning and fundraising, which can distract from legislative duties. Reelection strategies often focus on building a strong local presence, emphasizing achievements in securing federal funding or passing constituent-friendly legislation. Incumbents enjoy significant advantages, including name recognition and access to resources, but challengers can succeed by capitalizing on voter dissatisfaction or national trends. For example, the 2018 midterms saw a wave of Democratic victories fueled by opposition to the Trump administration, highlighting how national issues can overshadow local dynamics.

Reelection rates in the House are historically high, often exceeding 90%, but this doesn’t mean the process is predictable. Incumbents must navigate shifting demographics, economic conditions, and partisan polarization. Practical tips for candidates include leveraging social media to engage younger voters, building coalitions with local organizations, and focusing on issues like healthcare and the economy, which consistently rank high in voter priorities. For voters, staying informed about district boundaries and candidate platforms is essential, as is participating in primaries, where turnout is typically low but influence is high. Ultimately, the House’s election process and term structure reflect a delicate balance between stability and responsiveness, ensuring that the chamber remains a vibrant reflection of the American electorate.

Unveiling Bruce Gibson's Political Party Affiliation: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

As of 2023, the Republican Party holds a narrow majority in the House of Representatives.

The political party control of the House can change every two years, as all 435 seats are up for election during the midterm and presidential election cycles.

If the House is evenly split (218 seats each), the party with the Vice President’s tie-breaking vote in the Senate typically gains control, as the Vice President also serves as the President of the Senate.

While it is theoretically possible, it is highly unlikely due to the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties in U.S. politics. Third-party candidates rarely win House seats.