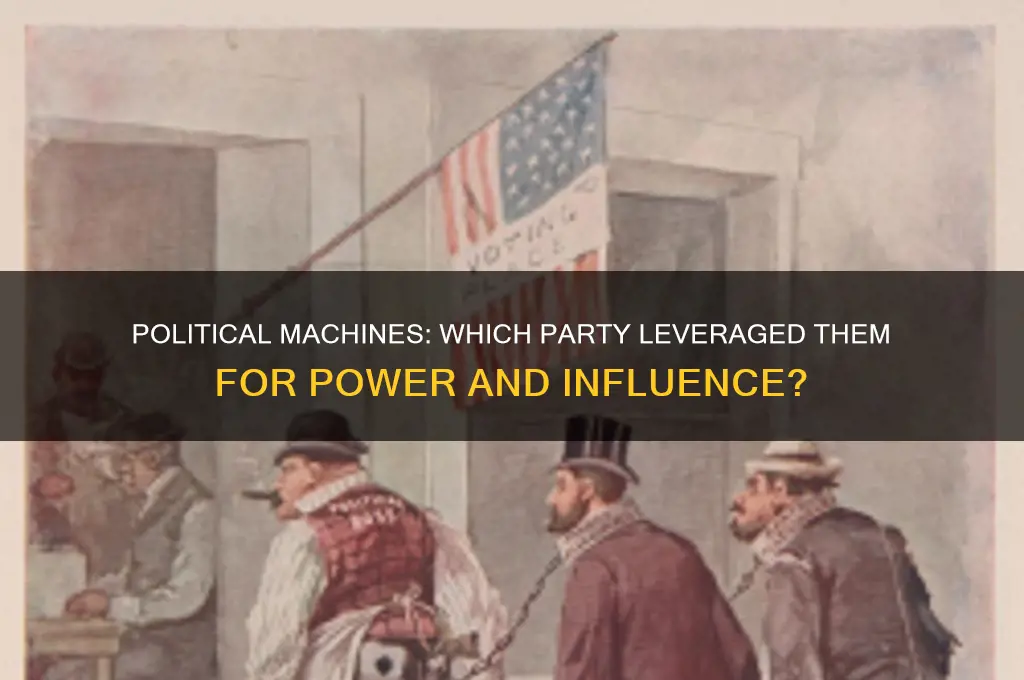

The use of political machines, which are organized networks of party members and supporters that operate to gain and maintain political power, has been a significant aspect of American political history. These machines often relied on patronage, voter mobilization, and sometimes questionable tactics to secure electoral victories. While both major parties have utilized such systems at various points, the Democratic Party is particularly notable for its association with political machines, especially during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Urban centers like New York, Chicago, and Boston saw the rise of powerful Democratic machines, such as Tammany Hall, which wielded considerable influence over local and state politics. These machines were often criticized for corruption and cronyism but also provided essential services to immigrant communities, solidifying their support base. Understanding which party used political machines sheds light on the evolution of American politics and the strategies employed to consolidate power.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Affiliation | Historically, the Democratic Party in the United States was most associated with political machines, particularly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. |

| Geographic Focus | Urban areas, especially in cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston, where immigrant populations were concentrated. |

| Key Figures | Boss Tweed (Tammany Hall in New York), Mayor Richard J. Daley (Chicago), and other local political bosses. |

| Methods | Patronage, voter mobilization, control of local government jobs, and quid pro quo arrangements. |

| Purpose | To maintain political power, secure votes, and control local and state governments. |

| Time Period | Peaked in the late 1800s to early 1900s, though remnants persisted into the mid-20th century. |

| Impact | Both positive (e.g., providing services to immigrants) and negative (e.g., corruption, graft). |

| Decline | Reforms, such as the Progressive Era, civil service reforms, and increased transparency in government. |

| Modern Relevance | While traditional political machines have largely disappeared, similar tactics (e.g., voter turnout operations) are still used by both major parties in the U.S. |

| Notable Examples | Tammany Hall (New York), Cook County Democratic Party (Chicago), and other urban political organizations. |

Explore related products

$20.41 $15.75

What You'll Learn

- Tammany Hall and the Democrats: Tammany Hall controlled New York City politics through patronage and voter mobilization

- Republican Machines in the North: GOP machines in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago dominated local politics

- Pendergast Machine in Kansas City: Tom Pendergast’s machine influenced Missouri politics and supported Harry Truman

- Cook County Democrats in Illinois: Daley’s machine in Chicago shaped state and national Democratic politics

- Urban Machines in the Gilded Age: Political machines thrived in industrial cities, exchanging favors for votes

Tammany Hall and the Democrats: Tammany Hall controlled New York City politics through patronage and voter mobilization

Tammany Hall, the notorious Democratic Party machine, dominated New York City politics for over a century by mastering two key tactics: patronage and voter mobilization. At its peak in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Tammany Hall operated as a well-oiled machine, distributing government jobs and favors to loyal supporters while ensuring high voter turnout through aggressive grassroots organizing. This system, though often criticized for corruption, created a powerful political network that kept the Democrats in control of the city’s government.

Consider the mechanics of patronage: Tammany Hall leaders like Boss Tweed and Charles Murphy rewarded party loyalists with jobs in city government, from clerks to police officers. This practice, known as the "spoils system," incentivized voters to support Tammany candidates in exchange for employment opportunities. For instance, during the 1860s, Tammany Hall controlled thousands of city jobs, effectively turning public positions into political tools. This system not only solidified Tammany’s power but also created a dependency cycle, as beneficiaries of patronage were unlikely to vote against their benefactors.

Voter mobilization was equally critical to Tammany Hall’s success. The machine employed a vast network of "ward heelers" who canvassed neighborhoods, registered voters, and ensured they turned out on Election Day. These operatives often provided practical assistance, such as transportation to polling places or even covering poll taxes for immigrants. Tammany Hall also catered to New York’s diverse immigrant populations, offering services like translation assistance and legal aid, which fostered loyalty among groups often marginalized by mainstream politics. This ground-level engagement was a key differentiator from other political organizations of the time.

However, Tammany Hall’s methods were not without controversy. Critics accused the machine of corruption, voter fraud, and exploiting the poor for political gain. Scandals, such as Boss Tweed’s embezzlement of millions from the city treasury, periodically tarnished Tammany’s reputation. Yet, despite these flaws, the machine’s ability to deliver tangible benefits to its constituents—jobs, services, and representation—kept it relevant and powerful. Tammany Hall’s legacy underscores the dual nature of political machines: while they can be vehicles for corruption, they also demonstrate the effectiveness of localized, service-oriented politics.

In analyzing Tammany Hall’s control over New York City, it’s clear that its success hinged on understanding and meeting the needs of its base. For modern political organizations, the takeaway is straightforward: voter mobilization and targeted patronage (in the form of policy benefits or services) remain potent tools for building and maintaining political power. Tammany Hall’s rise and fall serve as both a cautionary tale and a blueprint for the strategic use of political machines.

Are Both Political Parties Failing Black America? A Critical Analysis

You may want to see also

Republican Machines in the North: GOP machines in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago dominated local politics

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Republican political machines in Northern cities like Philadelphia and Chicago wielded immense power, shaping local politics through a blend of patronage, coercion, and strategic alliances. These machines, often led by charismatic bosses, controlled key institutions such as police departments, election boards, and public works, ensuring their dominance by delivering tangible benefits to constituents. For instance, Philadelphia’s Republican machine, under figures like Boies Penrose, mastered the art of rewarding loyalists with jobs and contracts while marginalizing opponents through voter suppression tactics like ballot-box stuffing. This system thrived on the exchange of favors for votes, creating a self-sustaining cycle of political control.

To understand the mechanics of these machines, consider their operational blueprint. First, they established a hierarchical structure with a boss at the top, captains in each ward, and precinct workers at the grassroots level. Second, they leveraged patronage by distributing government jobs and contracts to supporters, fostering dependency and loyalty. Third, they employed voter turnout strategies, including providing transportation to polls and offering incentives like food or small payments. However, caution must be exercised when examining these practices, as they often blurred the lines between public service and corruption. For example, while machines improved infrastructure and provided social services, they also engaged in graft and nepotism, undermining democratic principles.

A comparative analysis reveals that Republican machines in the North differed from their Democratic counterparts in the South and West in both composition and tactics. Northern GOP machines relied heavily on immigrant votes, particularly from German and Irish communities, by offering them a stake in the political system. In contrast, Southern Democratic machines often excluded minority groups, focusing instead on maintaining white supremacy. Additionally, Northern machines were more integrated into the national Republican Party, using their urban strongholds to influence federal policies. This distinction highlights the adaptability of political machines to regional demographics and political landscapes.

Persuasively, the legacy of these Republican machines offers lessons for modern politics. While their methods were often undemocratic, their ability to mobilize voters and deliver services underscores the importance of grassroots engagement. Today, political organizations can emulate their focus on local needs without resorting to corruption. For instance, campaigns can prioritize community outreach, voter education, and issue-based advocacy to build sustainable support. However, transparency and accountability must be non-negotiable to avoid the pitfalls of machine politics. By studying these historical examples, contemporary leaders can strike a balance between efficiency and ethics in political organizing.

Descriptively, the atmosphere of cities under Republican machine control was one of both order and tension. Streets buzzed with activity as precinct workers canvassed neighborhoods, while polling places became battlegrounds for influence. The machines’ presence was palpable in the form of posters, parades, and public works projects that bore their imprint. Yet, beneath the surface lay a complex web of allegiances and rivalries, with factions vying for power within the machine itself. This duality—of progress and corruption, unity and division—defined the era of GOP dominance in Northern cities, leaving an indelible mark on American political history.

Two-Party Dominance: Understanding the Current Landscape of American Politics

You may want to see also

Pendergast Machine in Kansas City: Tom Pendergast’s machine influenced Missouri politics and supported Harry Truman

The Pendergast Machine, led by Tom Pendergast, was a powerful political organization that dominated Kansas City and influenced Missouri politics during the early 20th century. Operating primarily within the Democratic Party, this machine exemplified how political machines could shape local and state governance through a combination of patronage, control over elections, and strategic alliances. Pendergast’s rise to power began in the 1920s, and by the 1930s, his machine had become a force to be reckoned with, delivering votes and resources to Democratic candidates in exchange for favors and influence.

One of the most notable legacies of the Pendergast Machine was its role in supporting Harry S. Truman’s political career. Truman, then a struggling politician, gained Pendergast’s backing in his 1934 Senate campaign. This endorsement provided Truman with the financial and organizational resources needed to secure victory. While Truman later distanced himself from Pendergast’s corrupt practices, the machine’s support was instrumental in launching his national political career, eventually leading to his presidency. This example highlights how political machines could act as both kingmakers and gatekeepers within their party.

The Pendergast Machine operated through a system of rewards and punishments, leveraging jobs, contracts, and favors to maintain loyalty. For instance, Pendergast controlled key positions in Kansas City’s government, ensuring that those who supported him benefited financially or professionally. However, this system also had a darker side, as it often involved voter fraud, intimidation, and ties to organized crime. Pendergast’s eventual downfall in 1939, following a tax evasion conviction, marked the end of his machine’s dominance but left a lasting impact on Missouri’s political landscape.

Comparatively, the Pendergast Machine shares similarities with other political machines of the era, such as Tammany Hall in New York City, but it stood out for its concentrated control over a single city and its ability to influence statewide politics. Unlike Tammany Hall, which operated within a larger metropolitan area, Pendergast’s machine was deeply rooted in Kansas City’s local economy and culture, making it both more insular and more effective in its immediate sphere. This localized focus allowed Pendergast to wield disproportionate power in Missouri’s Democratic Party.

For those studying political machines, the Pendergast Machine offers a cautionary tale about the balance between political organization and corruption. While it delivered tangible benefits to its supporters and helped elevate figures like Truman, its methods undermined democratic principles and public trust. Understanding this machine’s rise and fall provides insights into the mechanics of political power and the ethical dilemmas inherent in such systems. By examining its strategies and consequences, one can better appreciate the complexities of party politics and the enduring influence of such organizations.

Political Party Charity Donations: Legal, Ethical, and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$20.98 $39

Cook County Democrats in Illinois: Daley’s machine in Chicago shaped state and national Democratic politics

The Daley family's political machine in Cook County, Illinois, stands as a quintessential example of how local power structures can influence state and national politics. For much of the 20th century, the Daley machine, centered in Chicago, operated as a well-oiled organization that delivered votes, services, and patronage jobs in exchange for political loyalty. This system, rooted in the Democratic Party, not only dominated Chicago but also extended its reach to shape Illinois and national Democratic politics. By controlling key party positions, mobilizing voters, and leveraging resources, the Daleys exemplified the effectiveness and enduring legacy of political machines.

To understand the Daley machine’s impact, consider its operational mechanics. Richard J. Daley, mayor of Chicago from 1955 to 1976, built a network of ward bosses and precinct captains who ensured voter turnout and maintained party discipline. This grassroots structure allowed the machine to deliver overwhelming Democratic majorities in Cook County, which often swung statewide elections in Illinois. For instance, the machine’s ability to mobilize voters in Chicago was instrumental in securing victories for Democratic candidates in gubernatorial and senatorial races. This local dominance translated into significant influence over state legislative agendas, including funding for infrastructure projects that benefited Chicago and its suburbs.

The Daley machine’s reach extended beyond Illinois to national politics, particularly during the mid-20th century. Richard J. Daley’s role as a power broker in the Democratic Party was evident in his influence over presidential nominations and conventions. His control over the Illinois delegation at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, for example, showcased the machine’s ability to sway national party dynamics. Even after Richard J. Daley’s death, his son Richard M. Daley continued the family’s legacy, serving as Chicago’s mayor from 1989 to 2011 and maintaining the machine’s grip on local and state politics. This continuity highlights the machine’s adaptability and resilience in an evolving political landscape.

Critics argue that the Daley machine’s success came at the cost of transparency and accountability. The system relied heavily on patronage, with city jobs often awarded based on political loyalty rather than merit. This practice, while effective in maintaining control, raised ethical concerns and limited opportunities for those outside the machine’s network. However, proponents point to the machine’s ability to deliver tangible benefits to constituents, such as improved public services and infrastructure projects. For example, the construction of O’Hare International Airport and the modernization of Chicago’s public transportation system were direct outcomes of the machine’s influence.

In analyzing the Daley machine’s legacy, it’s clear that its impact on Democratic politics is both profound and complex. While its methods may seem outdated in today’s political climate, the machine’s ability to mobilize voters and deliver results offers lessons in political organization and strategy. For those studying political machines, the Daley family’s reign in Cook County serves as a case study in how local power structures can shape broader political landscapes. By examining its successes and shortcomings, we gain insight into the enduring influence of such systems on American politics.

Exploring Diverse Career Paths: Who Employs Political Scientists Today?

You may want to see also

Urban Machines in the Gilded Age: Political machines thrived in industrial cities, exchanging favors for votes

During the Gilded Age, industrial cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston became fertile ground for political machines, which operated as well-oiled systems of patronage and vote-trading. These machines, often tied to the Democratic Party in the North, thrived by exploiting the needs of immigrants and working-class citizens. For instance, Tammany Hall in New York City provided jobs, housing, and even coal for the poor in exchange for loyal votes. This quid pro quo system ensured political dominance while addressing immediate survival needs, creating a symbiotic relationship between machine bosses and their constituents.

The mechanics of these urban machines were both simple and ingenious. Machine operatives, known as "ward heelers" or "street bosses," acted as middlemen between the party and voters. They distributed favors—such as government jobs, legal assistance, or even cash—on election day. In return, voters were expected to cast their ballots for machine-backed candidates. This system was particularly effective in immigrant communities, where language barriers and unfamiliarity with American politics made reliance on machine assistance a practical necessity. The machines’ ability to deliver tangible benefits made them indispensable in the eyes of many urban dwellers.

Critics argue that these political machines undermined democratic principles by prioritizing loyalty over merit and fostering corruption. However, proponents contend that they filled a void left by inadequate government services, acting as de facto social welfare systems. For example, during economic downturns, machines often provided food and shelter to families in need, earning them goodwill and political capital. This dual role as both political power brokers and community caretakers highlights the complexity of urban machines in the Gilded Age.

To understand the legacy of these machines, consider their impact on modern politics. While overt vote-trading has diminished, the practice of exchanging favors for political support persists in subtler forms. Today’s campaign promises, targeted legislation, and strategic resource allocation echo the transactional nature of Gilded Age machines. By studying these historical systems, we gain insight into the enduring interplay between politics, power, and public need. Urban machines may have been a product of their time, but their principles continue to shape political strategies in contemporary society.

Political Parties' Role in Committee Appointments: Oversight or Influence?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party, particularly in urban areas like New York City, heavily relied on political machines during this period.

Yes, the Republican Party utilized political machines as well, especially in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, though they were less dominant than Democratic machines in many areas.

Tammany Hall in New York City is one of the most well-known Democratic political machines, led by figures like Boss Tweed.

No, in the South, both Democrats and Republicans used political machines, though Democrats were more dominant due to their stronghold in the region.

While political machines were more common in urban areas, they also operated in rural regions, often controlling local and state politics through patronage and influence.