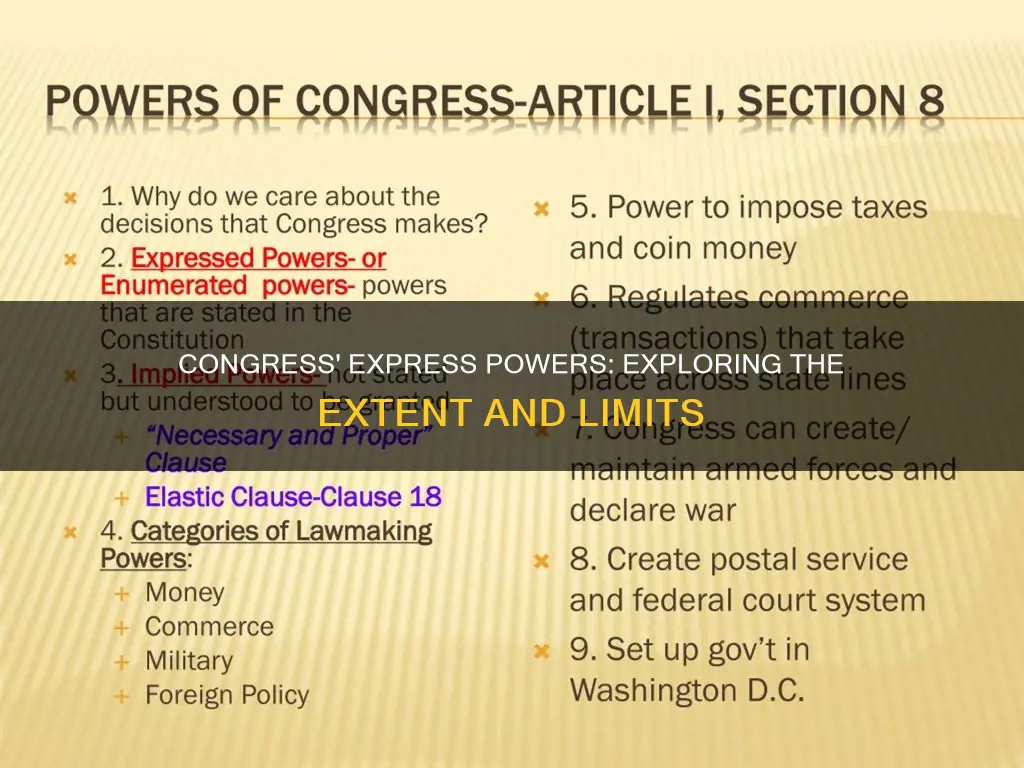

The United States Constitution grants Congress certain powers, known as expressed, explicit, or enumerated powers. These powers are vested in the Senate and the House of Representatives, which together form the United States Congress. The Constitution also outlines certain limitations on Congress, such as the Tenth Amendment, which states that any powers not expressly granted to the United States by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people. This article will explore the expressed powers of Congress, as outlined in the Constitution, and provide an overview of how these powers have been interpreted and exercised.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Power to tax and spend

The Constitution of the United States grants Congress the power to tax and spend. The Spending Clause, also known as the Taxing and Spending Clause, or the General Welfare Clause, states:

> "The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States" (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1).

This clause gives Congress the authority to impose and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, with the purpose of funding the country's debts and contributing to the general welfare. It is worth noting that the Constitution also includes regulations that outline the process by which Congress can authorise new taxes and expenditures. For instance, the Origination Clause dictates that "All Bills for Raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills" (U.S. Const. art. I, § 7, cl. 1).

Additionally, the Army Clause places a two-year limit on congressional appropriations for the army (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 12). This clause ensures that appropriations for the army are reviewed and approved regularly, preventing the unchecked accumulation of funds.

The power to tax and spend is a significant aspect of Congress's legislative authority. It enables Congress to generate revenue and allocate funds to address the country's debts, defence needs, and overall welfare. This power is further reinforced by Congress's ability to delegate regulatory powers to executive agencies, as affirmed by the Supreme Court. However, it is important to note that the Constitution also includes limitations on Congress's powers, such as the Implied Powers Clause, which restricts Congress to the powers explicitly granted or obviously implied within the Constitution.

Texas Constitution: What Rights Are Guaranteed?

You may want to see also

Authority to regulate commerce

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Indian tribes. This is known as the Commerce Clause, which is part of Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution.

The Commerce Clause gives Congress broad powers to regulate interstate commerce and restrict states from impairing interstate commerce. This clause has been interpreted broadly, with the federal government exercising powers not expressly granted to it by the states under the Constitution. For example, Congress has often used the Commerce Clause to justify exercising legislative power over the activities of states and their citizens, leading to ongoing controversy regarding the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in interpreting the Commerce Clause. Early Supreme Court cases, such as Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824, took a broad interpretation, holding that intrastate activity could be regulated under the Commerce Clause if it was part of a larger interstate commercial scheme. In the 1905 case of Swift and Company v. United States, the Court affirmed Congress's authority to regulate local commerce as long as it was part of a continuous "current" of commerce involving the interstate movement of goods and services.

However, in the 1995 case of United States v. Lopez, the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad powers under the Commerce Clause by adopting a more conservative interpretation. In this case, the Court held that Congress only has the power to regulate the channels of commerce, the instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce. Despite this, the Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time, and it continues to be a source of debate and interpretation by the Supreme Court.

In summary, the Authority to Regulate Commerce, granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, gives Congress significant power to regulate interstate commerce and restrict state actions that impair it. The interpretation of this clause has evolved through Supreme Court cases, shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

Shadow Health: Constitutional Health Questions Answered

You may want to see also

Ability to establish citizenship laws

The ability to establish citizenship laws is an expressed power of Congress. This power is derived from the Naturalization Clause of Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, which states that Congress has the power " [t]o establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization". This clause gives Congress the exclusive authority to determine the requirements and procedures for foreign nationals to become U.S. citizens.

The Naturalization Clause has been interpreted by the Supreme Court as vesting the power of naturalization solely within Congress. This interpretation was affirmed in early cases such as Chirac v. Lessee of Chirac (1817) and United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), where the Court recognized that the power to establish uniform rules of naturalization was granted exclusively to Congress by the Constitution.

Congress's power over naturalization extends beyond simply conferring citizenship. It includes the ability to revoke citizenship obtained through fraud or other unlawful means, as well as the power to set rules for when aliens may enter or remain in the United States. Citizenship can be granted through individual applications, special acts of Congress, or collectively through congressional action or treaty provisions.

The history of citizenship and naturalization in the United States has been complex and subject to change over time. For example, the first naturalization act enacted by Congress restricted naturalization to "free white persons", but this was later expanded to include persons of "African nativity and descent". The interpretation of the Naturalization Clause has also played a role in shaping the federal government's broad power over immigration, as seen in the case of Arizona v. United States (2012).

How Special Interests Get Their Way in Lawmaking

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Right to declare war

The US Constitution grants Congress the sole power to declare war. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution specifically lists as a power of Congress the power "to declare war," which gives the legislature the power to initiate hostilities. The framers of the Constitution were reluctant to give too much influence to a single person, so they denied the President the authority to go to war unilaterally.

The Continental Congress, composed of delegates from the thirteen colonies, exercised the powers of war and peace, raised an army, and created a navy before the Declaration of Independence. The powers to declare and wage war, conclude peace, make treaties, and maintain diplomatic relations with other sovereignties are all part of the Federal Government's powers of external sovereignty.

Congress has declared war on 11 occasions, including its first declaration of war with Great Britain in 1812. Congress approved its last formal declaration of war during World War II. Since then, it has agreed to resolutions authorizing the use of military force and continues to shape US military policy through appropriations and oversight.

While Congress has the power to declare war, Presidents have used military force without formal declarations or express consent from Congress on multiple occasions. For example, President Truman ordered US forces into combat in Korea, and President Reagan ordered the use of military force in Libya, Grenada, and Lebanon. Some commentators argue that these episodes establish a modern practice that allows the President considerable independent power to use military force. However, most scholars and commentators accept that presidential uses of force are valid if they fall within certain categories, although the scope of these categories remains contested.

Understanding Differences in Excerpts Through Comparative Analysis

You may want to see also

Ability to impeach a sitting president

The ability to impeach a sitting president is a fundamental power of Congress, derived from the U.S. Constitution, and it serves as a critical component of the system of checks and balances. This power is explicitly mentioned in Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution, which states: "The President, Vice President, and all Civil Officers of the United States shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors."

The impeachment process involves two key steps: the House of Representatives brings charges against the president, and the Senate conducts the impeachment trial. In the case of presidential impeachment, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the trial. The process begins when the House of Representatives approves articles of impeachment by a simple majority vote. These articles are then sent to the Senate, which acts as a High Court of Impeachment. The Senate considers the evidence, hears witnesses, and votes to acquit or convict the impeached president.

Throughout history, only three presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868, William J. Clinton in 1998, and Donald J. Trump in 2019 and 2021. Johnson was acquitted by the Senate by a single vote, and Trump was acquitted during his first impeachment trial in 2019. It is important to note that impeachment does not necessarily lead to removal from office. If the impeached official is found guilty, they are removed from office and may be barred from holding elected office in the future. However, if they are not found guilty, they may continue to serve in their position.

The impeachment process for a sitting president is a significant power vested in Congress, and it plays a crucial role in maintaining accountability and upholding the rule of law in the United States. It demonstrates the checks and balances within the U.S. political system, ensuring that no one branch or individual holds absolute power.

Counterfeiting Power: Understanding the Punishment's Reach

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The expressed powers of Congress are those granted to the federal government of the United States by the Constitution. These powers are listed in Article I, Section 8. They include the power to tax and spend for the general welfare and common defence, to borrow money, to regulate commerce with states and other nations, to establish citizenship and bankruptcy laws, and to impeach the President.

The Constitution expresses various limitations on Congress, such as the Tenth Amendment, which states that any powers not explicitly delegated to the federal government are reserved for the states or the people. States may not, for example, enter into treaties or alliances, grant letters of marque or issue bills of credit.

The implied powers of Congress are those that are not explicitly granted by the Constitution but are derived from the expressed powers. The Necessary and Proper Clause, for instance, gives Congress the authority to create laws that are deemed necessary and proper for carrying out the functions of the government.

Yes, the Supreme Court has ruled that Congress can delegate regulatory powers to executive agencies, as long as it provides a clear and governing principle. Congress has also asserted the power to investigate and compel cooperation with an investigation, which has been affirmed by the Supreme Court.